15 Reasons to Mediate Workers' Comp Cases

Reason No. 11. The mediator can facilitate communication, even when the parties are hostile.

Reason No. 11. The mediator can facilitate communication, even when the parties are hostile.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Teddy Snyder mediates workers' compensation cases throughout California through WCMediator.com. An attorney since 1977, she has concentrated on claim settlement for more than 19 years. Her motto is, "Stop fooling around and just settle the case."

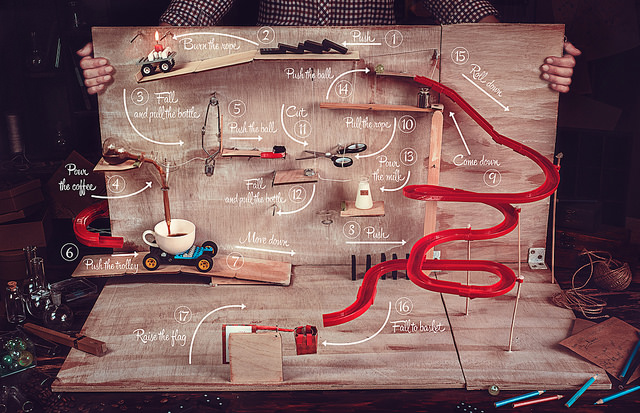

Without proper discipline, clear direction and effective communication, a project can derail before anybody realizes what happened.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Matt Flores is an architect with X by 2, a technology consulting company in Farmington Hills, Mich., specializing in software, data architecture and transformation projects for the insurance industry. He received a bachelor of science in computer science and astrophysics from the University of Michigan.

The system is remarkably complex in California, so here is a full treatment of regulations and case law.

What independent discovery rights do parties have in a contested workers’ compensation claim in California? The system is so complex that foundational education about discovery rights is required to improve and advocate for proper public policy and behavior by participants. This article is offered as a means to educate all parties about their discovery rights.

The law and the courts have stated that each party is entitled to a complete, accurate and documented record of all aspects of their case. This includes employment records, medical reports, accident records, claim files, etc. The right to obtain, review and prepare the record for any legal action is performed by discovery.

Discovery can be defined as processes used for obtaining information and copies of all legally relevant documents between parties or non-parties in a court proceeding as a legal requirement of the courts, before trial. The court in Fairmont Ins. Co. v. Superior Court, (2000) 22 Cal.4th 245 defined what happens if the right of discovery is not afforded parties. It states: “Without an opportunity for discovery as of right, parties would face substantial barriers to effective trial preparation, with results inimical to the overall purpose of the discovery statutes to reduce litigation costs, expedite trials, avoid surprise, and encourage settlement.”

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (1938) have been updated and annotated by James William Moore as well as numerous judges, lawyers and scholars and are the most referred to rules of legal procedure. Moore's Federal Practice (1997), 3rd Ed., vol. 4, pp. 1014-1016, lists what discovery is intended to accomplish: -- to give greater assistance to the parties in ascertaining the truth and in checking and preventing perjury; -- to provide an effective means of detecting and exposing false, fraudulent and sham claims and defenses; -- to make available, in a simple, convenient and inexpensive way, facts that otherwise could not be proved except with great difficulty; -- to educate the parties in advance of trial as to the real value of their claims and defenses, thereby encouraging settlements; -- to expedite litigation; -- to safeguard against surprise; -- to prevent delay; -- to simplify and narrow the issues; -- to expedite and facilitate both preparation and trial.

Thus, the scope of permissible discovery is one of reason, logic and common sense. In Glenfed Dev. Corp. v Superior Court, (1997) 53 CA 4th 1113, the court wrote that California's “pretrial discovery procedures are designed to minimize the opportunities for fabrication and forgetfulness, and to eliminate the need for guesswork about the other side's evidence, with all doubts about discoverability resolved in favor of disclosure.”

The legislature enacted California Code of Civil Procedure, also referred to as the California Civil Discovery Act (1986). §2019.010, which lists ways a party may obtain discovery: “Any party may obtain discovery by one or more of the following methods: (a) Oral and written depositions, (b) Interrogatories to a party, (c) Inspections of documents, things and places, (d) Physical and mental examinations, (e) Requests for admissions, (f) Simultaneous exchanges of expert trial witness information.

§2031 reads: “The court in which an action is pending may: -- order any party to produce and permit the inspection and copying or photographing, by or on behalf of the moving party, of any designated documents, papers, books, accounts, letters, photographs, objects or tangible things, not privileged, which constitute or contain evidence relating to any of the matters within the scope of the examination permitted by subdivision (b) of Section 2016 of this code and which are in his possession, custody, or control; or -- order any party to permit entry upon designated land or other property in his possession or control for the purpose of inspecting, measuring, surveying or photographing the property or any designated object or operation thereon within the scope of the examination permitted subdivision (b) of Section 2016 of this code. The order shall specify the time, place, and manner of making the inspection and taking the copies and photographs and may prescribe such terms and conditions as are just." [56 Cal.2d 370]

California Code of Civil Procedure Section 2017(a) states that “unless otherwise limited by order of the court in accordance with this article, any party may obtain discovery regarding any matter, not privileged, that is relevant to the subject matter involved in the pending action or to the determination of any motion made in that action, if the matter either is itself admissible in evidence or appears reasonably calculated to lead to the discovery of admissible evidence. Discovery may relate to the claim or defense of the party seeking discovery or of any other party to the action.”

In Irvington-Moore, Inc. v. Superior Court, (1993) 14 Cal.App.4th 733, the court states that “in establishing the statutory methods of obtaining discovery, the legislature intended that discovery be allowed whenever consistent with justice and public policy” for all litigation actions. It further states: “a party may demand that any other party produce and permit the party making the demand, or someone acting on the party’s behalf, to inspect and to copy a document that is in the possession, custody, or control, or control of the party on whom the demand is made.”

The same court relied on Greyhound Corp. v. Superior Court (1961), 56 Cal.2d 355, 382-383, 388 as to how statutes must be viewed, stating: “The statutes must be liberally construed in favor of discovery, and the courts must not extend the limits on discovery beyond those expressed by the legislature.

Other than to protect against possible abuse, the legislature did not differentiate between the right to one method of discovery and another, but intended the right to use each of the various vehicles of discovery to be inherently the same.

Selection of the method of discovery is made by the party seeking discovery; it cannot be dictated by the opposing party.”

The Discovery Act of 1986 codifies the liberal discovery concept providing a bona fide right for parties to conduct independent discovery in every litigated matter.

The Glenfed Dev. Corp. v. Superior Court, supra, court crystallized relevance. “In the context of discovery, evidence is 'relevant' if it might reasonably assist a party in evaluating its case, preparing for trial, or facilitating a settlement. Admissibility is not the test, and it is sufficient if the information sought might reasonably lead to other, admissible evidence.” (See also, Lipton v. Superior Court (1996) 48 Cal.App.4th 1599, 1611-1612).

One of the most significant cases for discovery in the workers’ compensation arena is Patricia Ann Hardesty et al., (John D. Hardesty, Jr., deceased), v. McCord & Holdren, Inc. and Industrial Indemnity Company (1976) 41 CCC 111. The ruling is: “Each party to a workers' compensation proceeding must make available to the other party for inspection all non-privileged statements of witnesses which are in his possession, or which might come into his possession before the time of trial, since the denial of discovery of non-privileged statement would unfairly prejudice the opposing party in preparing his case and would unduly expose him to the danger of surprise at trial.”

Labor Code §5710 is the authority on California workers’ compensation for taking the deposition of applicants, physicians, experts, employers and claims adjusters. (Note: Deposition can mean either the oral taking of a statement under oath or deposing of records).

§5710 reads: “The appeals board, a workers’ compensation judge, or any party to the action or proceeding, may, in any investigation or hearing before the appeals board, cause the deposition of witnesses residing within or outside the state to be taken in the manner prescribed by law of like depositions in civil actions in the superior courts of this state under Title 4 of Part 4 (commencing with Section 2016.010) of Part 4 of the Code of Civil Procedure.”

Case law supports the right of parties to subpoena records. This right can be found in Irvington-Moore, Inc. v. Superior Court. It states: “A party may demand that any other party produce and permit the party making the demand, or someone acting on the party’s behalf, to inspect and to copy a document that is in the possession, custody or control of the party on whom the demand is made.”

In workers’ compensation, the most common form of discovery to develop the record is obtained through documented business and medical records and witness depositions.

The right to issue a subpoena is found in California Evidence Code §1560(e), which states: “The subpoenaing party in a civil action may direct the witness to make the records available for inspection or by copying by the party’s attorney, the attorney’s representative or deposition officer as described in Section 2020.420 of the Code of Civil Procedure, at the witness’ business address under reasonable conditions during normal business hours.”

Subpoena rights are also buttressed by Workers’ Compensation Title 8 Regulation §10530: “The Workers' Compensation Appeals Board shall issue subpoenas and subpoenas duces tecum upon request in accordance with the provisions of Code of Civil Procedure sections 1985 and 1987.5 and Government Code section 68097.1.”

Workers’ Compensation Title 8 Regulation §10626 iterates: “Except as otherwise provided by law, all parties, their attorney, agents and physicians shall be entitled to examine and make copies of all or any part of physician, hospital or dispensary records that are relevant to the claims made and the issues pending in a proceeding before the Workers’ Compensation Appeals Board.”

Subpoena duces tecum means: "bring with you under penalty of law" and compels the party or non-party custodians of record to bring records that they have and to verify to the court that the documents or records have not been altered.

California Code of Civil Procedure §1985(c) states that: “The clerk, or a judge, shall issue a subpoena or subpoena duces tecum signed and sealed but otherwise in blank to a party requesting it, who shall fill it in before service.

An attorney at law who is the attorney of record in an action or proceeding, may sign and issue a subpoena to require attendance before the court in which the action or proceeding is pending or at the trial of an issue therein, or upon the taking of a deposition in an action or proceeding pending therein; the subpoena in such a case need not be sealed.

An attorney at law who is the attorney of record in an action or proceeding, may sign and issue a subpoena duces tecum to require production of the matters or things described in the subpoena.”

Title 8 Regulation §10530 provides for the WCAB issue subpoenas and subpoenas duces tecum upon request. Subpoenas for records are sent to one or multiple businesses.

California Evidence Code §1270 identifies meanings for business and evidence. “As used in this article, "a business" includes every kind of business, governmental activity, profession, occupation, calling or operation of institutions, whether carried on for profit or not.” This same code defines business record and the requirement that they are made under oath as to authenticity.

Section 1271 states: “Evidence of a writing made as a record of an act, condition or event is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule when offered to prove the act, condition or event if: (a) The writing was made in the regular course of a business; (b) The writing was made at or near the time of the act, condition, or event; (c) The custodian or other qualified witness testifies to its identity and the mode of its preparation; and (d) The sources of information and method and time of preparation were such as to indicate its trustworthiness.”

California Evidence Code §1560(e) states: “as an alternative to the procedures described in subdivisions (b), (c), and (d), the subpoenaing party in a civil action may direct the witness to make the records available for inspection or copying by the party's attorney, the attorney's representative, or deposition officer as described in Section 2020.420 of the Code of Civil Procedure.”

California Code of Civil Procedure §1985.3(a)(4) defines deposition officer as a person who meets the qualifications specified in Section 2020.420. The qualification states: “The officer for a deposition seeking discovery only of business records for copying under this article shall be a professional photocopier registered under Chapter 20 (commencing with Section 22450) of Division 8 of the Business and Professions Code, or a person exempted from the registration requirements of that chapter under Section 22451 of the Business and Professions Code. This deposition officer shall not be financially interested in the action, or a relative or employee of any attorney of the parties.”

California Business and Professions Code §22458 states: “A professional photocopier shall be responsible at all times for maintaining the integrity and confidentiality of information obtained under the applicable codes in the transmittal or distribution of records to the authorized persons or entities” and able to swear under oath as to its authenticity, establishing the proper evidential chain of custody.

The substantial evidence rule is applied by the California Appellate Court to the Workers’ Compensation Board decision. The substantial evidence rule is a principle that a reviewing court should uphold an administrative body's ruling if it is supported by evidence on which the administrative body could reasonably base its decision. "Substantial" means that the evidence must be of ponderable legal significance. It must be reasonable in nature, credible and of solid value; it must actually be substantial proof of the essentials that the law requires in a particular case.

Citing Petrocelli v. Workmen's Comp. Appeals Bd. (1975) 45 Cal.App.3d 635, the California Appellate Court in Georgia-Pacific Corp. v. Workers' Comp. Appeals Bd., (1983) 144 Cal.App.3d 72, wrote that “the respondent board's decision to uphold the finding of the workers’ compensation judge should not be disturbed where supported by substantial evidence or fairly drawn inferences . . .” -- thereby demonstrating that Appellate Court findings can set precedent on an administrative order/finding.

A party must be able to conduct independent discovery, or the case will not be litigated based on a complete and accurate record, which is a violation of the due process of law. (U.S. Const. amend. IV and XIV).

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Invisibility can be used deliberately to hide problems or shift responsibility, or inadvertently in ways that muddle lines of authority.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Dean K. Harring retired in February 2013 as the executive vice president and chief claims officer at QBE North America in New York. He has more than 40 years experience as a claims senior executive with companies such as Liberty Mutual, Commercial Union, Providence Washington, Zurich North America, GAB Robins and CNA.

This is National Suicide Prevention Week -- which is not only the right thing to do but is good business.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Bernie Dyme, a licensed clinical social worker, founded Perspectives, which provides workplace resource services to organizations internationally, including employee assistance programs (EAP), managed behavioral healthcare, organizational consulting, work/life and wellness.

To meet emerging challenges and requirements, simply adding processes or making one-off, isolated changes will not work.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Richard de Haan is a partner and leads the life aspects of PwC's actuarial and insurance management solutions practice. He provides a range of actuarial and risk management advisory services to PwC’s life insurance clients. He has extensive experience in various areas of the firm’s insurance practice.

Greg Galeaz is currently PwC’s U.S. insurance practice leader and has over 34 years of experience in the life and annuity, health and property/casualty insurance sectors. He has extensive experience in developing and executing business and finance operating model strategies and transformations.

These five reasons also apply to incumbent insurers that face innovative challengers.

* * *

While there are advocates for more aggressively pursuing driverless cars inside every major automaker, including GM, most strategic decision makers are in denial. Take a comment by Maarten Sierhuis, head of Nissan’s driverless research: "As a researcher, I want full autonomy! But the product planners maybe have another answer." This denial mirrors the rationalizations that industry leaders usually offer about disruptive technologies: Customers like the way things work now. We need to invest in the current business instead of risky new technology. New products would cannibalize our current products -- let’s make sure change is very gradual. We’ll miss our numbers if we get distracted. And so on. Like most rationalizations, these denials contain elements of truth. In GM’s case, there are very pressing issues that need its CEO’s attention. In addition to the ignition switch recall and safety issues, GM is facing challenging market issues in Europe, Russia and parts of South America. It is grappling with a sales slump for Cadillac. And it faces great opportunity but stiff competition in the fast-growing China market. GM also has a spotty track record for disruptive innovation. It invested early and heavily in factory automation and robotics, electric vehicles and fuel cells -- and failed to reap significant market benefits from those investments. Given all that, a multitude of internal voices are arguing against escalating GM’s response to Google. The only way to overcome the internal resistance that would otherwise smother a strategic driverless car initiative is for Mary Barra to make it a CEO-level imperative. That’s because the most critical success factor will be CEO attention, not money. No initiative that might so fundamentally change the core business—while also fighting for limited expertise and resources—can succeed without the strategic imperative that only the CEO can provide. Mary Barra must also anoint an internal champion with the resources at his or her disposal to make things happen. She must guard the initiative against corporate antibodies while also asking the tough questions needed to keep it focused rather than coddled. In reference to the Cobalt, Barra observed, rightly, “We will be better because of this tragic situation if we seize the opportunity.” GM will be even better if it also seizes the opportunities of driverless cars. The question is whether Barra can bring GM’s assets together into a strategic imperative that rivals the passion and pace of Google’s self-driving car effort.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Chunka Mui is the co-author of the best-selling Unleashing the Killer App: Digital Strategies for Market Dominance, which in 2005 the Wall Street Journal named one of the five best books on business and the Internet. He also cowrote Billion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn from the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last 25 Years and A Brief History of a Perfect Future: Inventing the World We Can Proudly Leave Our Kids by 2050.

Do not even discuss medical cost containment through group health networks and strategies. They simply do not apply to workers' comp.

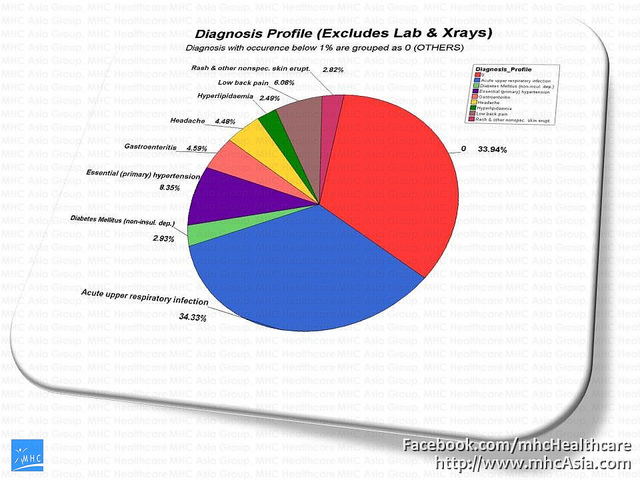

There are many reasons why workers' compensation managed care is so difficult, ranging from general economic cost pressures to the regulatory complexities faced by many large employers with multi-state work locations. Issues such as the ability to direct medical care, fee schedules, dispute resolution and the use of treatment protocols and provider networks vary from state to state.

Workers' comp medical costs have continued to outpace overall medical inflation for years. Twenty years ago, the typical ratio was 60/40 indemnity costs (lost-wages benefits) to medical costs. Today, that ratio has reversed.

Furthermore, workers' comp has always been susceptible to considerable cost-shifting both by injured workers and medical providers. Many injured workers without health insurance or with limited coverage have been suspected of submitting claims under workers comp to receive 100% "first dollar" coverage with no co-pays or deductibles. This is often known as the "Monday Morning Syndrome" -- weekend injuries from recreational activities get reported first thing Monday morning as "work-related." The support for this theory is that for years it was documented that the No. 1 time of reported injuries is between 9 and 10 Monday morning. In addition, if an injury or illness is reported as work-related the employee may be entitled to lost-wage replacement benefits, which results in a double incentive.

Medical providers also historically have had an incentive to shift costs to workers' comp. The best example are HMOs financed by pre-paid capitated rates for group health benefits. Work-related injuries are not included in group health plan coverage, allowing HMOs to bill additional charges on a fee-for-service basis. My former HMO had a large sign at the registration desk that read, "Please let us know if your medical care is work-related."

I was once hired by a major defense contractor during a competitive bid process and was told that all the other consultants had recommended it run its workers' comp program through its HMOs. My response was, "That is the last thing you want to do." The risk manager had a big smile on his face.

Many people in the industry were hoping that the ACA and the goal of universal coverage would eliminate the incentive for cost-shifting in workers' comp. In theory, that may be true. In reality, the ACA may have limited impact or, worse, actually create more incentives for cost-shifting.

The ACA has no direct impact because the various federal mandates for health insurance do not apply to workers' comp laws. Unlike Clinton-era health reform efforts, the ACA did not attempt to roll workers' comp into "one big program."

The ACA may exacerbate cost-shifting if health coverage costs will rise significantly for both employers and employees, which is widely predicted. The ACA premium rating factors virtually eliminate experience rating in favor of community rating for small employers, which helps pay for the added costs and mandated benefits. This will significantly drive up costs for many employers, with estimates as high as 50% above normal yearly premium increases.

Employees are also faced with the prospect of narrower networks and increased incentive to cost-shift, including the growing trend of consumer-driven health plans with high deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs.

Medical providers under intense cost pressures under the ACA may very well continue to cost-shift to the state workers' compensation systems and "first dollar" coverage to increase revenues. I fear that the high hopes that the ACA will help eliminate cost-shifting may go the way of "if you like your current health plan you can keep it."

One prominent proponent of the ACA just predicted that 80% of employers will actually eliminate company-paid health benefits by 2018 in favor of directing employees to the state exchanges because paying the $2,000 fine under the ACA for not providing health coverage will be cheaper than providing coverage.

Workers' compensation managed care is far more complex than managed care in group health benefits for many reasons, including; 50 different state laws and jurisdictional requirements, cost-shifting, fraud and abuse, overutilization of unnecessary or even harmful health services, excessive litigation and friction costs, historical animosities between labor and management, bureaucratic state agencies and an insurance industry and claim administrators who get a grade of C+ from many industry analysts.

If employers think the answers in containing workers' comp medical costs are in Washington, D.C., or the various state capitals in which they operate, they need to think again. The answer is in the mirror. Many employers are still searching for the cheapest claims administrator and not the best. Remember that "you get what you pay for."

The same goes for the overwhelming popular use of PPO "discount arrangements." If employers think they are saving money by looking for the cheapest doctor in town they couldn't be more misguided. The treating physician plays a key role in diagnosis and treatment, helps determine causation, degree of impairment and the length of disability and return-to-work. Family physicians and other primary care providers are rarely trained in occupational medicine or workers' comp laws and requirements and are notorious for granting indiscriminate time off work.

Employers must take a much more active role and provide the best and most appropriate medical care for sick and injured workers from the moment of injury or illness and establish better real-time communications between injured workers, medical providers, work supervisors and insurance companies and claims administrators.

Unfortunately, there is no magic bullet. But there is a rule of thumb: Do not even discuss medical cost containment with outside vendors or consultants who recommend broad-based group health networks and strategies. They simply do not apply to workers' comp and will do nothing but hurt an employer's ability to address the real cost drivers and complexities of state workers' comp laws, requirements and systems.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Dan Miller is president of Daniel R. Miller, MPH Consulting. He specializes in healthcare-cost containment, absence-management best practices (STD, LTD, FMLA and workers' comp), integrated disability management and workers’ compensation managed care.

And growth is just getting started, possibly presenting a once-in-a-career opportunity.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Marty Ellingsworth is president of Salt Creek Analytics.

He was previously executive managing director of global insurance intelligence at J.D. Power.

They do, if based on the right approach to design, and insurers need to adopt agile techniques to become more innovative.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Kal Nasser is a software developer, until recently with X by 2, a technology consulting firm in Farmington Hills, Mich., that specializes in IT transformation projects for the insurance industry. Its hands-on experts provide planning, architecture, leadership, turnaround and implementation services