Solution to High-Cost Indemnity Payments?

As firms struggle to manage costs for indemnity payments in workers' comp, card-based systems can make the process more efficient.

As firms struggle to manage costs for indemnity payments in workers' comp, card-based systems can make the process more efficient.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Dave Stair is the director of insurance payment solutions for DataPath. With nearly two decades of experience in the workers’ compensation industry in sales and consulting, Stair has an extensive track record helping workers' compensation payers manage and control claim costs.

Penetration is low in Latin America, particularly in life insurance, suggesting there is still significant growth ahead for the sector.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

James Littlewood has more than 12 years of experience in financial services, within both consulting as well as a specialty insurer in the UK. This experience has come across a broad range of project activities in insurance, reinsurance and banking, from strategic reviews through to implementation, as well as two years of line management in industry.

Drones clearly carry huge advantages, but they also raise tricky questions. What happens when they see things that should stay private?

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Chris Ketcham is the former visiting assistant professor of risk management and insurance at the University of Houston Downtown. He has an earned a doctorate from the University of Texas at Austin. With co-editor Jean Paul Louisot, Ph.D. he has written two books on enterprise risk management.

Direct, price-focused sales that emphasize speed are inevitably headed for problems because there's no time to do effective underwriting.

I recently read an article about "digital insurance stores." The article made some good points, though this was not one of them: "Agents need to go beyond their traditional roles as sellers of auto insurance because auto is fast becoming more commoditized." [emphasis added]

Once again, we're told that auto insurance is a commodity. In articles (see the “Price Check” article, for example) and webinars, we've communicated why auto insurance in particular, and personal lines insurance in general, is not a commodity, nor is it "fast becoming more commoditized." If anything, the opposite is true. In his paper, “Reevaluating Standardized Insurance Policies,” University of Minnesota Law School Professor Daniel Schwarcz writes about homeowners insurance:

"The current personal-lines insurance marketplace is largely organized around a myth. That myth is that personal-lines insurance policies are completely uniform. This myth explains regulatory rules that do nothing to promote insurance contract transparency….

“Different carriers' homeowners policies differ radically with respect to numerous important coverage provisions. A substantial majority of these deviations produce decreases in the amount of coverage relative to the presumptive industry standard…."

"If regulators do not act to substantially improve consumer protection in this domain, then it can be expected that coverage will continue to degrade for most carriers, in a modern-day reenactment of the race to the bottom in fire insurance that triggered the first wave of standardized insurance policies…."

Most of the agents I know recognize the demonstrated market share threat of direct, price-focused sales but don't fear it. Transparent competition is generally a good thing. Historically, intensified industry competition has, more often than not, resulted in more broadened, innovative products. That's no longer the case given the lack of transparency in the marketing of direct/online insurance products.

Given a focus almost entirely based on low-price, "painless" marketing by increasingly data-driven, tunnel-visioned and short-sighted financial bean counters, what we're likely seeing now is the beginning of a lemming-like stampede over a coverage oblivion cliff. Too many carriers today couldn't care less about the role their products play in protecting American families from financial ruin. They've convinced themselves (and much of America) that what consumers really want and need is fast, cheap and funny and that the way to sell that is through lizards with Australian accents and box store clerks who'll sell you a generic brown-paper-packaged insurance product at whatever price you tell her.

So-called experts and researchers who likely have never read their own auto policies and almost certainly have never compared two or more policies tell us that car insurance is a commodity where the best deal is the cheapest price that can be quoted in two minutes (yes, one company implies that it can ascertain your unique exposures and quote you the right product in two minutes, not 15, 7.5, or five). The experts tout the efficiencies of the Internet as the marketing channel that can bring even greater riches to insurers, as they predict the imminent demise of ignorant, un-hip Baby Boomer insurance agents who foolishly believe that consumers need consultation and advocacy. Note, too, that virtually all of these research reports focus on the advantages to the insurance company, with almost complete disregard to the obvious disadvantages to the American consumer.

But let's say they're right, that the Internet provides efficiencies that traditional marketing and sales channels cannot compete with. When all you can offer is "fast and cheap," at some point you can't provide that product any faster or cheaper. You've become as efficient as you possibly can be. So, when price is your only value proposition, what do you do at this point when you can't cut the expense ratio any closer? Presumably, you'd look to, by far, the biggest component of premium – losses and loss adjustment expenses. So, how do you reduce that component, which accounts for 75% to 80% of premium, to continue to compete on price?

One way would be to actually return to underwriting. But you can't do that when you're quoting in two minutes. So, what does that leave? Reducing coverage or becoming more restrictive in claims handling practices. After all, who will know? Everyone agrees that "car insurance" is a commodity, so no one is considering what the policy actually covers or doesn't cover. Until claim time. And, on average, that's only once every seven years or so. So, again, no one much will notice…other than the families who lose just about everything they own because they bought an inferior product.

As Mr. Schwarcz opines, that's exactly where the industry is headed in auto insurance unless agents make their case to the consuming public about the value of consultative selling and claims advocacy. And unless regulators return to carefully vetting the products they approve for the marketplace to ensure that they do not leave unreasonable, potentially catastrophic coverage gaps for insureds and that they reasonably protect the public from becoming victims to overly restrictive policy exclusions and limitations.

Copyright 2015 by the Independent Insurance Agents & Brokers of America. Reprinted with permission.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

William C. Wilson, Jr., CPCU, ARM, AIM, AAM is the founder of Insurance Commentary.com. He retired in December 2016 from the Independent Insurance Agents & Brokers of America, where he served as associate vice president of education and research.

There are many questions you should ask before allowing staff to carry while working—and a “No” to any of them should give you pause.

If you own a bricks-and-mortar firearms retail store, at some point you will have to deal with this question, if you haven't already. There are both pros and cons to having your employees carry in your store while they're on the clock, so let's look at the list of them.

Cons

There are a number of questions you should be asking before allowing your staff to carry while working—and a "No" to any of them should give you pause.

Do my employees have an acceptable level of training to use a firearm in a life-threatening situation should the need arise? Do they even know how to discern which situations call for the potential use of deadly force and which ones require less-lethal remedies?

Is the potential for the use of deadly force realistic for your store design? In many jurisdictions, law enforcement trains to a "21-foot rule" to determine when deadly force can be an option, this being the distance needed for an officer to effectively draw a weapon and fire when confronted. Inside your store, though, the reaction space may be more like three feet across the gun counter. Knowing that, does allowing your staff to carry become more of a liability—are they more prone to a gun grab, for instance, or will they simply not have the time and distance needed to draw and fire in a close-quarters attack—than an asset?

Do my business and health insurance policies cover any and all aftermath resulting from a use of force by an employee?

Are there any local, state or federal laws that prevent my employees from carrying their personal firearms while at work or restrictions to carrying while working that would hurt my business?

Do your employees need concealed carry permits to carry legally in your store? Does your store need any kind of special security licensing to permit your employees to work while armed?

Are your employees trained in first aid?

Are you in a high-crime area? If so, is your area one where crimes occur with some frequency when businesses are open?

Is your business located remotely or is challenging for law enforcement to get to in a timely manner?

There's another concern you should address, and that is the one having to do with the impression that having a staff of armed employees makes on your customers.

"I worked in a firearms retail store and indoor shooting range in the D.C.-metro area for many years back in the 1990s," Jennifer Pearsall, the National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF) director of public relations, told me. "For many years the county our store resided in refused to sign off on concealed carry permits, but when some state legislation made the application process more universal, naturally everyone wanted to carry. That was certainly true for several of our employees, especially since our store had been burglarized a couple times, though always after hours. But the owner decided not to allow it. We had a customer base consisting of everyone from serious antique collectors to competitive pistol shooters and hunters, but we also regularly had novices in the store. The owner didn't want to give those newcomers and those quieter collectors we often had in the store an impression that was in any way intimidating or unapproachable. That's a legitimate consideration, emphasis on 'consideration.' What's normal to us as professionals in the industry isn't always normal to those on the outside—you do have to put yourself in your customers' shoes and ask, 'What would I think if this was my first time walking through my store's door?' Too, a store that has an extremely active 3-Gun competitor or cowboy action shooting crowd might make a different decision about in-store carry than one that routinely fills their first-time shooter safety classes. There is no right or wrong answer to this beyond the one you come up with yourself based on what you know about your customer base as it exists now and how you want to expand that base."

Pros

Many of the pros to allowing your employees to carry while at work should be obvious, but let's take a look at some of them in greater detail. Some of these are predicated on your having a policy regarding their ability to carry in your store, while others address a "Yes" response to an item in the "con" list above.

Your employees have some level of training in self-defense and are active participants in the shooting sports outside of work. These things can certainly help make them better salespeople.

Your employees have been educated about the laws of open and concealed carry in your state and can help pass that information on to customers seeking the same.

If you had to obtain special licensing or institute a training program to enable your employees to carry during work, this might reduce your risk of liability to your insurance carrier.

Having your employees carry during open business hours, especially open carry, is a visual deterrent to criminals.

Employee carry can serve as an advantage for stores located in remote areas and far away from emergency responders.

When presented as "normal" and "not a big deal," open carry by your staff could help mitigate apprehension in customers new to your store and open the door for discussion on subjects like the legality of concealed carry in your area, what kind of gun and holster to buy and other subjects that will interest these novice gun owners.

By putting all the precursors in place to allowing your employees to carry—their training, store carry policy and any necessary licensing, discussions with your insurance carriers and lawyer—you are better equipped to deal with a deadly force situation if one does occur. This includes everything from first aid and working with law enforcement arriving on the scene to handling the media, counseling and any workman's comp claims for employees, insurance claims and any matters that need to be handled by a court.

Only you can decide what's right for your store when it comes to allowing your employees to carry while they're working. Whatever decision you make, simply by working through the lists of pros and cons here and adding in any other factors that could affect your store and livelihood, you've improved how you do business.

As they say, work smarter, not harder.

This article was originally published on NSSF.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

William "Bill" Napier has more than 30 years’ experience in safety/security/loss prevention, serving in leadership roles such as site manager, corporate manager and director. Businesses have included small and growing retail chains as well as Fortune 500 companies. Napier is currently a consultant to the firearms industry.

Yes, policy admin systems need to be modernized, but that's just the start. Underwriters need more to optimize the use of their expertise.

As SMA's Karen Furtado wrote in last month's blog post about core systems, "Now that the insurance industry recognizes modernization as an indispensable tool for remaining competitive, it is worthwhile to take a step back and look at the technical capabilities that insurers really need." With underwriting, this requires a platform that extends beyond the policy administration system and makes optimal use of the expertise of the underwriters themselves.

Today's environment is full of infinite possibilities for the future of underwriting. Advances in the electronic exchange of information have benefited the insurance industry in major ways. One example is apparent with the portals and exchanges that are making it easier for agents to submit business opportunities. Given the ease, more submissions are coming in the door. This increased workload coupled with new data sources for validation and verification leaves underwriters at a tipping point. With increased demand and increasingly more complex variables, they need a solution that gives them enhanced capabilities that extend beyond the same old way of doing things.

In today's competitive market, the ability to issue a quote for every desired risk is critical. The power literally has shifted to the palm of the consumers' hands, where they get instant gratification via their mobile devices. For some insurers, not being able to handle the volume of quotes that are being submitted to them means leaving significant money on the table.

Therefore, a modern policy admin system is necessary for its ability to automate the processes that are performed by the underwriting department. These systems automate the data capture, base rating and rules and final pricing, and they manage formulas and document production for all risks. They process transactions for new business, renewals, endorsements, cancellations, reinstatement, etc. But, for complex risks, the risk analyses and evaluations that are determined based on information about credit, hazards, financials and loss experience are made outside the policy admin system. Automation supporting these decision-making processes takes place outside the policy admin system. SMA research shows just 37% of the entire underwriting process is managed via the policy admin system.

Before that harsh reality sets in, realize that the modern underwriting platform is not, should not be and cannot be a standalone system. Nor is the modern policy admin system a standalone solution. Now, the two (underwriting platform and policy admin system) should be connected, with the ability to perform the complex functions mentioned above.

One of our SMA imperatives is: "Interconnect Intelligence for Underwriting." Nothing in modern insurance can happen in isolation, in a traditional silo. Those days are over, but, fortunately, the technology is available to support current and future needs. The key is finding the right connection points, the right technology and the right fit for your organization. Today's real-time, big-data, high-volume market dictates the same from your company's system, and that is why modern support for underwriting requires more than just a policy admin system.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Deb Smallwood, the founder of Strategy Meets Action, is highly respected throughout the insurance industry for strategic thinking, thought-provoking research and advisory skills. Insurers and solution providers turn to Smallwood for insight and guidance on business and IT linkage, IT strategy, IT architecture and e-business.

In this era of free agent employees, companies need to stop their resistance and encourage employees to develop personal brands.

Where does a company brand begin and end? Does it embrace the employees -- people who are the brand -- or suffocate them?

More and more, I'm being asked by people -- in both the corporate sphere, among those trying to control the brand perception, and by individuals attempting to expand their own platform and network -- what are the dimensions of personal branding, and how does it fit with the corporate brand? What is personal branding? How do you do it? What's the real value of the “[insert your name here] Brand”? And how do companies use it to their advantage?

Unfortunately, official corporate reaction generally is, “Why should I invest in employee loyalty when they're at work scrolling through LinkedIn contacts and job postings, attempting to leverage the corporate brand as they are looking for their next job?”

We have all become keenly aware there are fewer and fewer retirement parties and gold watch presentations these days. We are fixated on our next gig because -- well, because, what other option is there?

The employer-employee relationship has changed dramatically over time. Any perception of reciprocal loyalty has evaporated, along with the time cards and company picnics. We are no longer searching for the job of a lifetime, instead, we're in search of a lifetime of jobs.

A wisely led company should recognize that personal branding is an important issue for employees and should encourage it. A study by Brightedge says, “Companies that have a greater proportion of their employees on LinkedIn have more followers on their company pages.” This means employees will improve equity-brand trust by attracting other great employees, improving brand reputation.

That's a good thing.

Sadly, many times companies fail to recognize the benefits. They don't realize these free agent employees can be strong assets to their company if they are recognized as thought leaders.

How did this employee free agent mentality start?

Roots of an Issue

Capitalism is, intrinsically, a dynamic system of supply and demand. Financial and intellectual capital jets about these days faster than ever. Markets grow and collapse right and left.

Once upon a time, it was good advice to tell college kids to prepare for careers with multiple stops and regale them with stories of that slow but steady climb up the corporate ladder. Now we tell people of all ages: Prepare for multiple careers!

This change has created what I call the free agent employee model, which has caused a rift in company and employee relationships. Why? Because companies assume these “free agents” aren't looking for long-term commitment (e.g., the Careerbuilder.com report that says 76% of full-time workers would leave their job if the right opportunity came along.) But how should employees think about job security and company loyalty, especially when facing the likelihood of downsizing, right sizing, re-organizing and lay-offs along their career paths?

Check out N.F.L. free agents, a large talent pool of players willing to join the team offering the highest bid. This “jumping ship” approach reminds me of the show "Shark Tank," except it's not limited to fledgling entrepreneurs or N.F.L. athletes -- it's now everyone.

Look at Millennials; they're the ones who have seen their parents adapt to the aftermath of the recession, and they're the ones who will continue this free agent way of thinking. Actually, 50% of the workforce will be made up of Millennials by 2030, according to PEW. Companies need to take note by putting an emphasis on employee engagement.

Employees Need Lovin' – Even Free Agents

Companies that fear and want to crush the free agent mentality are missing important opportunities to capitalize on employees' personal branding.

If employees feel a sense of fulfillment when working for us, which is employee engagement, and have a strong connection with their manager, which again is employee engagement, then they're more likely to commit to our company and become brand advocates, which can help bring in more customers and new employee talent right to our doorsteps.

Remember, employees will stay for the right manager, not the right job – and will leave for the same reason.

When you think about it, it's the front-line employees who are dealing with the customers every day. They're the ones who help build the relationship between the brand and the customer. Who wouldn't want to encourage that? And they're the investment that represents the brand as much as the CEO every day.

However, executives tend to think their role plays a bigger part in the public's eye than employees. According to a recent New Weber study, “50% of executives expect that CEO reputation will matter even more to company reputation in the next few years.” In fact, the Edelman Trust Barometer says, “Employees rank higher in pu blic trust than a firm's PR department, CEO or founder. 41% of us believe that employees are the most credible source of information regarding their business.”

What if companies engaged and promoted their employees more? Would the numbers reflect it? Would companies focus less on CEO transparency and public and media relations and more on employee engagement?

Moving Forward

The post-recession way of thinking is here to stay – at least in the foreseeable future. If we want our employees to start being loyal, then we've got to meet them halfway. We have to embrace their free agent way of thinking. And we have to engage them. Then, maybe we can stop looking over employees' shoulders, fearing free agency, and give employees a company they believe in promoting.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Donna Peeples is chief customer officer at Pypestream, which enables companies to deliver exceptional customer service using real-time mobile chatbot technology. She was previously chief customer experience officer at AIG.

Worst policy ever? Letting life insurance policy holders allocate funds based on week-old information may cost Aviva a big piece of its business.

OK, there have been some amazingly stupid contracts written over the years. But among people who really ought to know what they're doing, one from France probably does take the biscuit. It's a hybrid life insurance/savings product that allows a policy holder to allocate capital among various funds. Nothing very strange or stupid there. However, here's the catch:

It allows the policy holder to switch funds this Friday based on the prices of the funds last Friday. And that isn't just stupid, that's doolally. It may be the worst policy ever issued.

The basic background is that this was a reasonably popular sort of contract among French insurance companies back in the 1980s and '90s. Take out a life insurance contract (usually, to get the tax privileges that go with such a contract) and use it as a savings vehicle. You can swap between bond, equity funds and so on as you go along. Given the speed of the post in those days, and the general rarity with which people fiddled with their investments, prices of the funds would be published on a Friday, and you had until the next one to switch around your investments based on those prices.

The world has changed since then: We can all look up asset prices in seconds now. And some of those insurance policy holders noticed. They started aggressively managing (as they have every right to do) the savings in their funds. You can see what's coming here. If I can trade Thursday on last Friday's prices, I'm likely to do pretty well, because I know what has happened to prices. And so it is with some of these players.

Does a 70% compound profit per annum sound like a juicy investment return to you? It does to me.

Of course, there has been all sorts of scrambling to try and get out of this. The company managing the contracts, Aviva, has been refusing to move funds, for example. And it should be said that most of the people with these contracts were, umm, gently maneuvered out of them over the years both from this company and others. You know the sort of thing: “Sirs, we want to make a slight change to the T&Cs of your contract; here is €100 for your trouble in signing this and returning it to us.” That change being that you're no longer allowed to shift on the basis of 20/20 hindsight.

Max Herve-George was not tempted by such offers. So, he's been making those alarmingly high profits, isn't budging and has been up and down the courts system (winning pretty much all the while) to hold Aviva to that contract.

It gets better: Herve-George is, under the terms of the contract, allowed to add more funds. He's made arrangements with a hedge fund or two (who wouldn't like 70%-per-annum returns?) to inject perhaps a further €20 million…..and you can see where this is going, can't you? At some point, he owns the company, then France and then the entire planet. FT Alphaville gleefully calculates for us when this is going to happen. Might not be in my lifetime. but it's likely to be in Max's.

Of course, this isn't actually going to happen. As Herb Stein pointed out, if something cannot go on forever, then it won't. But the interesting question is, well, what is going to stop it?

There are really only two possibilities. One is that France, or the French courts, shred contract law. And, believe me, over things like savings and life insurance, the French are very serious indeed about that law. Or, Max ends up owning Aviva, the company that sold him the contract.

As it happens, an old friend of mine is working as an adviser somewhere in this case. And we've been chewing the fat over which way it's going to turn out. Our best bet is that Max ends up owning Aviva France.

The thinking is along these lines: First, France really does take extremely serious ly the law surrounding these sorts of investment, life insurance and pension policies.

We're both reminded of the case of Jeanne Calment. France has a system of reverse mortgages. You, a nice little bourgeois lawyer, say, look around you and see some little old lady living in a nice apartment that she owns. Say, a 90-year-old little old la dy with no surviving descendants. So, she'd quite like to swap the apartment after her death for an income stream now. A reverse mortgage of sorts. So you do this, and she goes on to be the longest-living human being ever (OK, for completists, leaving out the Antediluvians). In 1965, at age 90 and with no heirs, Calment signed a deal to sell her apartment to lawyer André-François Raffray, on a contingency contract. Raffray, then aged 47 years, agreed to pay her a monthly sum of 2,500 francs until she died. Raffray ended up paying Calment the equivalent of more than $180,000, which was more than double the apartment's value. After Raffray's death from cancer at the age of 77, in 1995, his widow continued the payments until Calment's death in 1997, at age 122.

French law is really very strict about such things. So, we just don't think that the courts are going to shred the contract: Yo do so would be shredding that basic sanctity of contract law.

Yes, it's true, you can't write a contract making yourself a slave, and there are some other restrictions. But you are indeed allowed to write some amazingly stupid contracts, and you will be held to them.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Tim Worstall is a fellow at the Adam Smith Institute in London, a writer here and there on this and that. He has written for the Times of London, Daily Telegraph, Express, Independent, City AM, Wall Street Journal and Philadelphia Inquirer and online for the ASI, IEA, Social Affairs Unit, Spectator, the Guardian, the Register and Techcentralstation.

Insurers have a huge role in cyber security, not only to pick up the pieces after an event occurs but to educate and prepare people.

Because of the recent and hugely public spate of cyber "events," the world of cyber security and subsequently cyber insurance is firmly in overdrive. According to the UK Department for Innovation & Skills, 81% of large businesses and 60% of small businesses suffered a cyber-security breach in the last year, and the average cost of breaches to business has nearly doubled since 2013.

We have all seen the headlines, from Sony last year to British Airways earlier this month to the French TV Channel TV5Monde. The severity and importance of each of these has material impacts on not only their ability to do business but also their brand and reputation as a customer, employee and partner.

Sony was clearly hugely public, by far one of the biggest and most public I have seen hit the news for a long time. It was all over most news channels, causing outcry from customers and employees, some of whom threatened to sue their employer or former employer for failing to protect their data. Sony, of course, has had many attacks, including one taking down its PlayStation online platform for days on end. As for BA, the first I heard of this was an email saying, "Someone has accessed your account." Please come change your password! This is the brand that I trust with my personal details, my location and much more.

Finally, TV5Monde seems to be particularly worrying to me. In a scene that reminded me of the wonderfully played Elliot Carver from 007's "Tomorrow Never Dies," the media giant was quite simply disabled, their TV taken off air, their public online presence taken over and more. An attack of this scale and power to me simply highlights what Hollywood has been portraying for years (remember "Die Hard," where the bad guys take over the airport by hot wiring a few cables nearby?). Interestingly, subsequent reports again point to human error here – for instance, a TV interview showed passwords stuck to Post-It notes.

If we are under any doubt by the frequency, scale and impact of attacks, I found a great website (www.informationisbeautiful.net) recently that visualizes some of the data breaches by year, industry and size, reason and more; see here for the full interactive chart.

Cyber threats have been defined by many; however, as with many other critical business issues, lots of other things are being added to the overall "cyber" definition. The recent report from the UK Government on UK cyber security: the role of insurance talks through both the threat and, importantly, the opportunity for insurers.

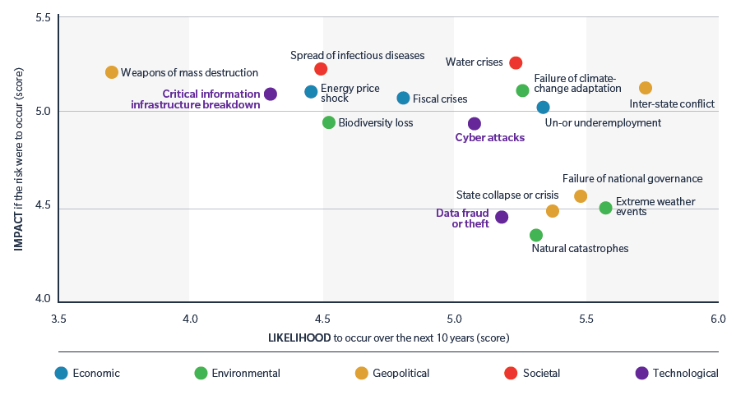

The World Economic Forum in its 10th Annual Global Risks Report has cyber risks up with water crisis and natural catastrophe and ahead of WMD, infectious disease and fiscal crisis (in terms of likelihood of occurrence). Given what we have all experienced in the last recession, I don't think we could have a stronger wake up call.

- Top Global Risks According to the World Economic Forum

- Top Global Risks According to the World Economic Forum

For now, and certainly as I write today, there is a small correlation between cyber-attacks and loss of human life. However, as we become ever more connected with IoT (Internet of Things) or IoE (Internet of Everything), future devices will all be connected. In the latest report, the government said that 14 billion objects are already connected to the Internet, 40 million of them in the UK. By 2020, it could be as many as 100 billion worldwide.

The upside of being able to monitor your heart pacemaker or your insulin levels from an app are already upon us; "wearables" is the buzzword for 2015. When these devices move from monitoring to controlling, the threat just increases. A cyber-attack at a local level, shutting down a hospital, airport, city traffic system, taking over a driverless car or airplane – it's far too easy to paint a picture here.

What's the role of the insurer in all of this?

The insurance provider has a huge role in this, not only to pick up the pieces when an event occurs, but also across the entire lifecycle. At the outset, we have an opportunity to better educate the market on cyber risks in general, in creating insurance capacity for the event and ultimately better prepare ourselves for the continuing advancement and frequency of attacks.

This goes far beyond the cyber essentials to better prepare small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) and large enterprises alike. This is not collecting a badge; this is time to get ready for a battle. Not just a battle against cyber threats, but a battle for your reputation and brand. A brand that says to your employees, customers and partners, you can trust me with your information – I have a plan in place that's tried and tested! The government scheme has covered the bare minimum essentials, which is like passing your driving theory test. We need expert drivers here to navigate roads no one has previously seen.

The UK, and London market specifically, is already well-placed given its deep experience in insuring against specialty risks, but capacity in the market will continue to increase as the threats and frequency of events increases, giving rise to new, more tailored products and opportunities for the entire market. How long will it be before we all have our own personal cyber Insurance policy?

Move to prevention rather than cure

We need to better help organizations truly understand the cost of putting this right after the event. As an example, some estimate that the cost of the Target breach in the U.S. has cost them north of $100 million to correct. In the early earnings call post the event, Target executives said, "The breach resulted in $17 million of net expenses in the fourth quarter..., with $61 million of total expenses partially offset by the recognition of a $44 million insurance receivable."

Hindsight is wonderful, but perhaps a fraction of this upfront would have saved this money and, importantly, provided time to focus on the business strategy, not remedial work.

Reputation, Reputation, Reputation

It's already been widely discussed, but insuring an organization's reputation is challenging for a number of reasons. Of course, almost anything can be insured, but defining what the impact is and then working out what you need to be covered for will no doubt bring additional challenge for something that most would describe as intangible. The Insurance Times has a good piece here on this.

More importantly, what's the short-, medium- or long-term impact and value on the reputational damage? Take your favorite or most-used retailer, give it all your personal financial data and shopping habits. It then suffers a breach – how likely are you to use or recommend the retailer again? Maybe you would forgive it for one breach; what if it happened again? It's too easy to move. I read that in the UK you are more “likely to suffer a theft from your bank than a physical burglary” these days.

Does this affect your future choice? How long does it take you to re-establish trust with your customers, employees and partners?

Typically, reputation risk is around 5% to 20% of cyber cost. However, in reality, it's the gift that can keep on giving, that no one really wants.

What if you are an online-only business? What if you were the ones who disrupted your market through technology and now that has been taken away from you. You don't have the luxury of physical outlets as a backup or alternative part of your business plan. Dealing with other breaches such as shoplifting has been an occurrence since retail began, but these were isolated to the individual locations.

SMEs, especially, are not as well-equipped. On one hand, digital makes access open to anyone to create a new business, but on the other hand we must now factor in the cost of doing business online, of which cyber is a now business-critical.

What do you think?

Are we prepared and doing enough across the sector? Is this at the forefront of your business continuity strategy? Have you a plan in place to protect your employees, customers and partners? Do you have adequate cover that is well-enough defined? Are you investing ahead of the curve to prevent it?

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Nigel Walsh is a partner at Deloitte and host of the InsurTech Insider podcast. He is on a mission to make insurance lovable.

He spends his days:

Supporting startups. Creating communities. Building MGAs. Scouting new startups. Writing papers. Creating partnerships. Understanding the future of insurance. Deploying robots. Co-hosting podcasts. Creating propositions. Connecting people. Supporting projects in London, New York and Dublin. Building a global team.

In the face of fears on data breaches, companies can protect themselves with insurance -- some of which they likely already own.

Target’s $19 million settlement with MasterCard[1] underscores very significant sources of potential exposure that often follow a data breach that involves payment cards. Retailers and other organizations that accept those cards are likely to face—in addition to a slew of claims from consumers and investors— claims from financial institutions that seek to recover losses associated with issuing replacement credit and debit cards, among other losses. The financial institution card issuers typically allege, among other things, negligence, breach of data-protection statutes and non-compliance with Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards (PCI DSS). Likewise, as Target’s recent settlement illustrates, organizations can expect to face claims from the payment brands, such as MasterCard, VISA and Discover, seeking substantial fines, penalties and assessments for purported PCI DSS non-compliance.

These potential sources of liability can eclipse others. While consumer lawsuits often get dismissed for lack of Article III standing,[2] for example, or may settle for relatively modest amounts,[3] the Target financial institution litigation survived a motion to dismiss[4] and involved a relatively high settlement amount as compared with the consumer litigation settlement. So did TJZ’s prior $24 million settlement with card issuers.[5] The current settlement involves only MasterCard,[6] moreover, and the Target financial institution litigation will proceed with any issuer of MasterCard-branded cards that declines to partake of the $19 million settlement offer. The amended class action in the Target cases alleges that the financial institutions’ losses “could eventually exceed $18 billion.”[7]

Organizations should be aware that these significant potential sources of data breach and payment brand liability may be covered by insurance, including commercial general liability insurance (CGL), which most companies have in place, and specialty cybersecurity/data privacy insurance.

Here are five steps for securing coverage for data breach and PCI DSS-related liability:

Step 1: Look to CGL Coverage

Coverage A: “Property Damage” Coverage

Payment card issuers typically seek damages because of the necessity to replace cards and, often, also specifically allege damages because of the loss of use of those payment cards, including lost interest, transaction fees and the like. By way of illustration, the amended class action complaint in the Target litigation alleges:

The financial institutions that issued the debit and credit cards involved in Target’s data breach have suffered substantial losses as a result of Target’s failure to adequately protect its sensitive payment data. This includes sums associated with notifying customers of the data breach, reissuing debit and credit cards, reimbursing customers for fraudulent transactions, monitoring customer accounts to prevent fraudulent charges, addressing customer confusion and complaints, changing or canceling accounts and facing the decrease or suspension of their customers’ use of affected cards during the busiest shopping season of the year.[8]

The litigation further alleges that “plaintiffs and the FI [financial institution] class also lost interest and transaction fees (including interchange fees) as a result of decreased, or ceased, card usage in the wake of the Target data breach.”[9]

These allegations fall squarely within the standard-form definition of covered “property” damage under CGL Coverage A. Under Coverage A, the insurer commits to “pay those sums that the insured becomes legally obligated to pay as damages because of … ‘property damage’… caused by an ‘occurrence’”[10] that “occurs during the policy period.”[11] The insurer also has “the right and duty to defend the insured against any … civil proceeding in which damages because of … ‘property damage’ … are alleged.”[12]

Importantly, the key term “property damage” is defined to include not just “physical injury to tangible property” but also “loss of use of tangible property that is not physically injured.” The key definition in the current standard-form CGL insurance policy states as follows:

For the purposes of this insurance, electronic data is not tangible property.

In this definition, "electronic data" means information, facts or programs stored as or on, created or used on or transmitted to or from computer software, including systems and applications software, hard or floppy disks, CD-ROMs, tapes, drives, cells, data processing devices or any other media that are used with electronically controlled equipment.[13]

Although the current definition states that “electronic data is not tangible property,” to the extent this standard-form language may be present in the specific policy at issue (coverage terms should not be assumed; rather the specific policy language at issue should always be carefully reviewed),[14] the limitation is largely, perhaps entirely, irrelevant in this context because card issuer complaints, like the amended class action complaint in the Target litigation, typically allege damages because of the need to replace physical, tangible payment cards.[15] The complaints further often expressly allege that the issuers have suffered damages because of a decrease or cessation in the card usage.

These types of allegations are squarely within the “property damage” coverage offered by CGL Coverage A, and courts have properly upheld coverage in privacy-related cases where allegations of loss of use of property are present.[16]

Coverage B: “Personal and Advertising Injury” Coverage

There is significant potential coverage for data breach-related liability, including card issuer litigation, under CGL Coverage B. Under Coverage B, the insurer commits to “pay those sums that the insured becomes legally obligated to pay as damages because of ‘personal and advertising injury,’”[17] which is “caused by an offense arising out of [the insured’s] business … during the policy period.”[18] Similar to Coverage A, the policy further states that the insurer “will have the right and duty to defend the insured against any … civil proceeding in which damages because of … ‘personal and advertising injury’ to which this insurance applies are alleged.”[19]

The key term “personal and advertising injury” is defined to include a list of specifically enumerated offenses, which include “oral or written publication, in any manner, of material that violates a person’s right of privacy.”[20]

Considering this key language, courts have upheld coverage under CGL Coverage B for claims arising out of data breaches and for a wide variety of other claims alleging violations of privacy rights.[21] It warrants mention that, although the trial court in the Sony PlayStation data breach litigation recently ruled against coverage, the trial court’s decision -- which turned on the court’s finding that, essentially, Coverage B is triggered only by purposeful actions by the insured (Sony) and not by the actions of the third parties who hacked into its network -- that decision is currently on appeal to the New York Appellate Division and may soon be reversed. Nowhere in the insuring agreement or its key definition does the CGL policy require any action by the insured. As the coverage’s name “Commercial General Liability” indicates, the coverage does not require intentional action by the insured, as argued by the insurers in the Sony case, but rather is triggered by the insured’s liability, i.e., the insurer commits to pay sums that the insured “becomes legally obligated to pay” that “arise out of” the covered “offenses.” The broad insuring language, moreover, extends to the insured’s liability for publication “in any manner,” i.e., via a hacking attack or otherwise. The cases cited by the insurer in the Sony case are factually inapposite and interpret entirely different policy language. Indeed, Sony’s insurer, Zurich, itself acknowledged in 2009 that CGL policies may provide coverage for data breaches via hacking, which by definition involves third-party actions.[22]

Organizations also should be aware that the Insurance Services Office (ISO), the insurance industry organization responsible for drafting standard-form CGL language, recently promulgated a series of data breach exclusionary endorsements.[23] ISO acknowledged that there currently is data breach coverage for hacking activities under CGL policies. In particular, ISO stated that the new exclusions may be a “reduction in personal and advertising injury coverage”—the implication being that there is coverage in the absence of the new exclusions.

At the time the ISO CGL and CLU policies were developed, certain hacking activities or data breaches were not prevalent and, therefore, coverages related to the access to or disclosure of personal or confidential information and associated with such events were not necessarily contemplated under the policy. As the exposures to data breaches increased over time, stand-alone policies started to become available in the marketplace to provide certain coverage with respect to data breach and access to or disclosure of confidential or personal information.

To the extent that any access or disclosure of confidential or personal information results in an oral or written publication that violates a person’s right of privacy, this revision may be considered a reduction in personal and advertising injury coverage.[24]

Other than the trial court’s decision in the Sony case, no decision has held that an insured must itself publish information to obtain CGL Coverage B coverage, and a number of decisions have appropriately upheld coverage for liability that the insured has resulting from third-party publications.[25]

The bottom line: There may be very significant coverage under CGL policies, including for data breaches that result in the disclosure of personally identifiable information and other claims alleging violation of a right to privacy, including claims brought by card issuers.

Step 2: Look to “Cyber” Coverage

Organizations are increasingly purchasing so-called “cyber” insurance, and a major component of the coverage offered under most “cyber” insurance policies is coverage for the spectrum of issues that an organization typically confronts in the wake of a data breach incident. This usually includes, not only defense and indemnity coverage in connection with consumer litigation and regulatory investigation, but also defense and indemnity coverage in connection with card issuer litigation. By way of example, one specimen policy insuring agreement states that the insurer will “pay … all loss” that the “insured is legally obligated to pay resulting from a claim alleging a security failure or a privacy event.” The key term “privacy event” includes “any failure to protect confidential information,” a term that is broadly defined to include “information from which an individual may be uniquely and reliably identified or contacted, including, without limitation, an individual’s name, address, telephone number, Social Security number, account relationships, account numbers, account balances, account histories and passwords.” “Loss” includes “compensatory damages, judgments, settlements, pre-judgment and post-judgment interest and defense costs.” Litigation brought by card issuers is squarely within the coverage afforded by the insuring agreement and its key definitions.

Importantly, a number of “cyber” insurance policies also expressly cover PCI DSS-related liability. By way of example, the specimen policy quoted above expressly defines covered “loss” to include “amounts payable in connection with a PCI-DSS Assessment,” which is defined as follows:

“PCI-DSS assessment” means any written demand received by an insured from a payment card association (e.g., MasterCard, Visa, American Express) or bank processing payment card transactions (i.e., an “acquiring bank”) for a monetary assessment (including a contractual fine or penalty) in connection with an insured’s non-compliance with PCI Data Security Standards that resulted in a security failure or privacy event.

This can be a very important coverage, given that, as the recent Target settlement illustrates, organizations face substantial liability arising out of the card brand and association claims for fines, penalties and assessments for purported non-compliance with PCI DSS. The payment card brands routinely claim that an organization was not PCI DSS-compliant and that the PCI forensic investigator assigned to investigate compliance routinely determines that the organization was not compliant at the time of a breach. As the payment industry has stated, “no compromised entity has yet been found to be in compliance with PCI DSS at the time of a breach.”[26]

The bottom line: “Cyber” insurance policies may provide broad, solid coverage for the costs and expenses that organizations may incur in connection with card-issuer litigation and payment brand claims alleging PCI non-compliance.

Step 3: Look to Other Potential Coverage

It is important not to overlook other types of insurance policies that may respond to cover various types of exposure flowing from a breach. For example, there may be coverage under directors’ and officers’ (D&O) policies, professional liability or errors and omissions (E&O) policies and commercial crime policies. After a data breach, companies are advised to provide prompt notice under all potentially implicated policies, excepting in particular circumstances that may justify refraining to do so, and to carefully evaluate all potentially applicable coverages.

Step 4: Don’t Take “No” For an Answer

Unfortunately, even where there is a legitimate claim for coverage under the policy language and applicable law, an insurer may deny a claim. Indeed, insurers can be expected to argue, as Sony’s insurers argued, that data breaches are not covered under CGL insurance policies. Nevertheless, insureds that refuse to take “no” for an answer may be able to secure valuable coverage.

If, for example, an insurer reflexively raises the “electronic data” exclusion in response to a claim under CGL Coverage A, which purports to exclude, under the standard form, “[d]amages arising out of the loss of, loss of use of, damage to, corruption of, inability to access or inability to manipulate electronic data,”[27] insureds are encouraged to point out that the damages alleged by card issuers for replacing physical cards and for lost interest and transaction fees, etc., resulting from loss of use of those cards, are clearly outside the purview of the exclusion. Likewise, if an insurer raises the standard “Recording And Distribution Of Material Or Information In Violation Of Law” exclusion, insureds are encouraged to point out that the exclusion has been narrowly interpreted, does not address common-law claims and has been held inapplicable where the law at issue fashions relief for common law rights.[28]

Importantly, exclusions and other limitations to coverage are construed narrowly against the insurer and in favor of coverage under well-established rules of insurance policy interpretation,[29] and the burden is on the insurer to demonstrate an exclusion’s applicability.[30]

Step 5: Maximize Cover Across the Entire Insurance Portfolio

Various types of insurance policies may be triggered by a data breach, and the various triggered policies may carry different insurance limits, deductibles, retentions and other self-insurance features, together with various different and potentially conflicting provisions addressing, for example, other insurance, erosion of self-insurance and stacking of limits. For this reason, in addition to considering the scope of substantive coverage under an insured’s different policies, it is important to carefully consider the best strategy for pursing coverage in a manner that will maximize the potentially available coverage across the insured’s entire insurance portfolio. By way of example, if there is potentially overlapping CGL and “cyber” insurance coverage, remember that defense costs often do not erode CGL policy limits, and structure the coverage strategy accordingly.

When facing a data breach, companies should carefully consider the insurance coverage that may be available. Insurance is a valuable asset. Before a breach, companies should take the opportunity to carefully evaluate and address their risk profile, potential exposure, risk tolerance, sufficiency of their existing insurance coverage and the role of specialized cyber coverage. In considering that coverage, please note that there are many specialty “cyber” products on the market. Although many, if not most, of these policies purport to cover many of the same basic risks, including data breaches and other types of “cyber” and data privacy-related risk, the policies vary dramatically. It is important to carefully review policies for appropriate coverage prior to purchase and, in the event of a claim, to carefully review the scope of all potentially available coverage.

This article was first published in Law360.

[1] Target Strikes $19M Deal With MasterCard Over Data Breach, Law360 (April 15, 2015). The settlement is contingent upon at least 90% of the eligible MasterCard issuers accepting their alternative recovery offers by May 20.

[2] See, e.g., No Data Misuse? No Standing For Data Breach Plaintiffs, Law360 (April 24, 2014).

[3] Target Will Pay Consumers $10M To End Data Breach MDL, Law360, New York (March 19, 2015).

[4] See, e.g., Target Loses Bid to KO Banks' Data Breach Litigation, Law360 (April 15, 2015).

[5] TJX Reaches $24M Deal With MasterCard Issuers, Law360 (April 2, 2008).

[6] The company is reported to be in similar negotiations with Visa.

[7] In re: Target Corporation Customer Data Security Breach Litigation, MDL No. 14-2522 (PAM/JJK) (D. Minn), at ¶ 87 (filed August 1, 2014).

[8] Id., ¶ 2 (emphasis added).

[9] Id., ¶ 86 (emphasis added).

[10] ISO Form CG 00 01 04 13 (2012), Section I, Coverage A, §1.a., §1.b.(1).

[11] Id., Section I, Coverage A, §1.b.(2).

[12] Id., Section I, Coverage A, §1.a.; Section V, §18.

[13] ISO Form CG 00 01 04 13 (2012), Section V, §17 (emphasis added).

[14] In the absence of such language, a number of courts have held that damaged or corrupted software or data is “tangible property” that can suffer “physical injury.” See, e.g., Retail Sys., Inc. v. CNA Ins. Co., 469 N.W.2d 735 (Minn. Ct. App. 1991); Centennial Ins. Co. v. Applied Health Care Sys., Inc., 710 F.2d 1288 (7th Cir. 1983) (California law); Computer Corner, Inc. v. Fireman’s Fund Ins. Co., No. CV97-10380 (2d Dist. Ct. N.M. May 24, 2000).

[15] See also Eyeblaster, Inc. v. Federal Ins. Co., 613 F.3d 797 (8th Cir. 2010).

[16] See, e.g., District of Illinois in Travelers Prop. Cas. Co. of America v DISH Network, LLC, 2014 WL 1217668 (C.D, Ill. Mar. 24, 2014); Columbia Cas. Co. v. HIAR Holding, L.L.C., 411 S.W.3d 258 (Mo. 2013).

[17] ISO Form CG 00 01 04 13 (2012), Section I, Coverage B, §1.a.

[18] Id., Section I, Coverage B, §1.b..

[19] Id.. Section I, Coverage B, §1.a.; Section V, §18.

[20] Id.. Section V, §14.e.

[21] See, e.g., Hartford Cas. Ins. Co. v. Corcino & Assocs,. 2013 WL 5687527 (C.D. Cal. Oct. 7, 2013).

[22] Zurich, Data security: A growing liability threat (2009), available at http://www.zurichna.com/NR/rdonlyres/23D619DB-AC59-42FF-9589-C0D6B160BE11/0/DOCold2DataSecurity082609.pdf (emphasis added).

[23] These new exclusions became effective in most states last May 2014. One of the exclusionary endorsements, titled “Exclusion - Access Or Disclosure Of Confidential Or Personal Information,” adds the following exclusion to the standard form policy:

This insurance does not apply to:

Access Or Disclosure Of Confidential Or Personal Information

“Personal and advertising injury” arising out of any access to or disclosure of any person’s or organization’s confidential or personal information, including patents, trade secrets, processing methods, customer lists, financial information, credit card information, health information or any other type of non public information.

CG 21 08 05 14 (2013). See also Coming To A CGL Policy Near You: Data Breach Exclusions, Law360 (April 23, 2014).

[24] ISO Commercial Lines Forms Filing CL-2013-0DBFR, at pp. 3, 7-8 (emphasis added).

[25] See, e.g., Hartford Cas. Ins. Co. v. Corcino & Assocs,. 2013 WL 5687527 (C.D. Cal. Oct. 7, 2013).

[26] Visa: Post-breach criticism of PCI standard misplaced (March 20, 2009), available at http://www.computerworld.com.au/article/296278/visa_post-breach_criticism_pci_standard_misplaced/

[27] CG 00 01 04 13 (2012), Section I, Coverage A, §2.p.

[28] See, e.g., Hartford Cas. Ins. Co. v. Corcino & Assocs,. 2013 WL 5687527 (C.D. Cal. Oct. 7, 2013). For example, in the Corcino case, the court upheld coverage for statutory damages arising out hospital data breach that compromised the confidential medical records of nearly 20,000 patients, notwithstanding an express exclusion for “personal and advertising Injury …. [a]rising out of the violation of a person’s right to privacy created by any state or federal act.” Corcino and numerous other decisions underscore that, notwithstanding a growing prevalence of exclusions purporting to limit coverage for data breach and other privacy related claims, there may yet be valuable privacy and data breach coverage under “traditional” or “legacy” policies that should not be overlooked.

[29] See, e.g., 2 Couch on Insurance § 22:31 (“the rule is that, such terms are strictly construed against the insurer where they are of uncertain import or reasonably susceptible of a double construction, or negate coverage provided elsewhere in the policy”).

[30] See, e.g., 17A Couch on Insurance § 254:12 (“The insurer bears the burden of proving the applicability of policy exclusions and limitations or other types of affirmative defenses”).

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Roberta Anderson is a director at Cohen & Grigsby. She was previously a partner in the Pittsburgh office of K&L Gates. She concentrates her practice in the areas of insurance coverage litigation and counseling and emerging cybersecurity and data privacy-related issues.