Workers' Comp Issues to Watch in 2015

Among them: Generic drugs will drive prices <i>up</i>; policies on marijuana may have to change; and new healthcare models are emerging.

Among them: Generic drugs will drive prices <i>up</i>; policies on marijuana may have to change; and new healthcare models are emerging.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Mark Walls is the vice president, client engagement, at Safety National.

He is also the founder of the Work Comp Analysis Group on LinkedIn, which is the largest discussion community dedicated to workers' compensation issues.

To reverse the long-term decline in those buying life insurance, companies must become relevant to younger, healthier people.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Anand Rao is a principal in PwC’s advisory practice. He leads the insurance analytics practice, is the innovation lead for the U.S. firm’s analytics group and is the co-lead for the Global Project Blue, Future of Insurance research. Before joining PwC, Rao was with Mitchell Madison Group in London.

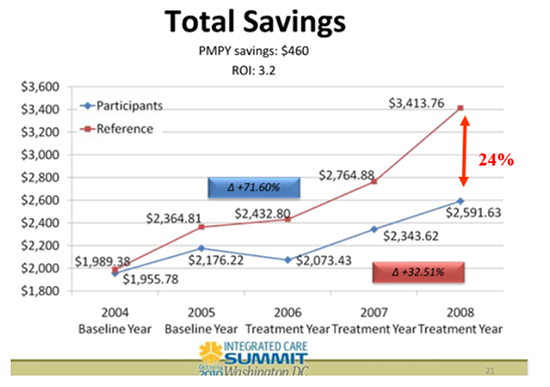

The authors welcome his recent, pro-wellness posting but question his data, including the slide most often used to demonstrate wellness' value.

(6) Why doesn’t anyone on the Koop Committee notice any of these “unfortunate mislabelings” until several years after we point out that they are in plain view?

(7) Why is it that every time HFC admits lying, the penalty that you assess -- as president of the Koop Award Committee -- is to anoint their programs as “best practices” in health promotion? (See Eastman Chemical and Nebraska in the list below.) Doesn’t that send a signal that Dr. Koop might have objected to?

(8) Whenever HFC publishes lengthy press releases announcing that its customers received the “prestigious” Koop Award, it always forgets to mention that it sponsors the awards. With your post’s emphasis on “the spirit of full disclosure” and “transparency,” why haven’t you insisted HFC disclose that it finances the award (sort of like when Nero used to win the Olympics because he ran them)?

(9) Speaking of “best practices” and Koop Award winners, HFC’s admitted lies about saving the lives of 514 cancer victims in its award-winning Nebraska program are technically a violation of the state’s anti-fraud statute, because HFC accepted state money and then misrepresented outcomes. Which is it: Is HFC a best practice, or should it be prosecuted for fraud?

(10) RAND Corp.’s wellness guru Soeren Mattke, who also disputes wellness ROIs, has observed that every time one of the wellness industry’s unsupportable claims gets disproven, wellness defenders say they didn’t really mean it, and they really meant something else altogether. Isn’t this exactly what you are doing here, with the “mislabeled” slide, with your sudden epiphany about following USPSTF guidelines and respecting employee dignity and with your new position that ROI doesn’t matter any more, now that most ROI claims have been invalidated?

(11) Why are you still quoting Katherine Baicker’s five-year-old meta-analysis claiming 3.27-to-1 savings from wellness in (roughly) 16-year-old studies, even though you must be fully aware that she herself has repeatedly disowned it and now says: “There are very few studies that have reliable data on the costs and benefits”? We have offered to compliment wellness defenders for telling the truth in every instance in which they acknowledge all her backpedaling whenever they cite her study. We look forward to being able to compliment you on truthfulness when you admit this. This offer, if you accept it, is an improvement over our current Groundhog Day-type cycle where you cite her study, we point out that she’s walked it back four times, and you somehow never notice her recantations and then continue to cite the meta-analysis as though it’s beyond reproach.

To end on a positive note, while we see many differences between your words and your deeds, let us give you the benefit of the doubt and assume you mean what you say and not what you do. In that case, we invite you to join us in writing an open letter to Penn State, the Business Roundtable, Honeywell, Highmark and every other organization (including Vik Khanna’s wife’s employer) that forces employees to choose between forfeiting large sums of money and maintaining their dignity and privacy. We could collectively advise them to do exactly what you now say: Instead of playing doctor with “pry, poke, prod and punish” programs, we would encourage employers to adhere to USPSTF screening guidelines and frequencies and otherwise stay out of employees’ personal medical affairs unless they ask for help, because overdoctoring produces neither positive ROIs nor even healthier employers. And we need to emphasize that it’s OK if there is no ROI because ROI doesn’t matter.

As a gesture to mend fences, we will offer a 50% discount to all Koop Committee members for the Critical Outcomes Report Analysis course and certification, which is also recognized by the Validation Institute. This course will help your committee members learn how to avoid the embarrassing mistakes they consistently otherwise make and (assuming you institute conflict-of-interest rules as well to require disclosure of sponsorships) ensure that worthy candidates win your awards.

(6) Why doesn’t anyone on the Koop Committee notice any of these “unfortunate mislabelings” until several years after we point out that they are in plain view?

(7) Why is it that every time HFC admits lying, the penalty that you assess -- as president of the Koop Award Committee -- is to anoint their programs as “best practices” in health promotion? (See Eastman Chemical and Nebraska in the list below.) Doesn’t that send a signal that Dr. Koop might have objected to?

(8) Whenever HFC publishes lengthy press releases announcing that its customers received the “prestigious” Koop Award, it always forgets to mention that it sponsors the awards. With your post’s emphasis on “the spirit of full disclosure” and “transparency,” why haven’t you insisted HFC disclose that it finances the award (sort of like when Nero used to win the Olympics because he ran them)?

(9) Speaking of “best practices” and Koop Award winners, HFC’s admitted lies about saving the lives of 514 cancer victims in its award-winning Nebraska program are technically a violation of the state’s anti-fraud statute, because HFC accepted state money and then misrepresented outcomes. Which is it: Is HFC a best practice, or should it be prosecuted for fraud?

(10) RAND Corp.’s wellness guru Soeren Mattke, who also disputes wellness ROIs, has observed that every time one of the wellness industry’s unsupportable claims gets disproven, wellness defenders say they didn’t really mean it, and they really meant something else altogether. Isn’t this exactly what you are doing here, with the “mislabeled” slide, with your sudden epiphany about following USPSTF guidelines and respecting employee dignity and with your new position that ROI doesn’t matter any more, now that most ROI claims have been invalidated?

(11) Why are you still quoting Katherine Baicker’s five-year-old meta-analysis claiming 3.27-to-1 savings from wellness in (roughly) 16-year-old studies, even though you must be fully aware that she herself has repeatedly disowned it and now says: “There are very few studies that have reliable data on the costs and benefits”? We have offered to compliment wellness defenders for telling the truth in every instance in which they acknowledge all her backpedaling whenever they cite her study. We look forward to being able to compliment you on truthfulness when you admit this. This offer, if you accept it, is an improvement over our current Groundhog Day-type cycle where you cite her study, we point out that she’s walked it back four times, and you somehow never notice her recantations and then continue to cite the meta-analysis as though it’s beyond reproach.

To end on a positive note, while we see many differences between your words and your deeds, let us give you the benefit of the doubt and assume you mean what you say and not what you do. In that case, we invite you to join us in writing an open letter to Penn State, the Business Roundtable, Honeywell, Highmark and every other organization (including Vik Khanna’s wife’s employer) that forces employees to choose between forfeiting large sums of money and maintaining their dignity and privacy. We could collectively advise them to do exactly what you now say: Instead of playing doctor with “pry, poke, prod and punish” programs, we would encourage employers to adhere to USPSTF screening guidelines and frequencies and otherwise stay out of employees’ personal medical affairs unless they ask for help, because overdoctoring produces neither positive ROIs nor even healthier employers. And we need to emphasize that it’s OK if there is no ROI because ROI doesn’t matter.

As a gesture to mend fences, we will offer a 50% discount to all Koop Committee members for the Critical Outcomes Report Analysis course and certification, which is also recognized by the Validation Institute. This course will help your committee members learn how to avoid the embarrassing mistakes they consistently otherwise make and (assuming you institute conflict-of-interest rules as well to require disclosure of sponsorships) ensure that worthy candidates win your awards.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Al Lewis, widely credited with having invented disease management, is co-founder and CEO of Quizzify, the leading employee health literacy vendor. He was founding president of the Care Continuum Alliance and is president of the Disease Management Purchasing Consortium.

Senior executives under financial pressure often take actions that cause distractions. Here are three ways to let employees solve the problems.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Brian Cohen is currently an operating partner with Altamont Capital Partners. He was formerly the chief marketing officer of Farmers Insurance Group and the president and CEO of a regional carrier based in Menlo Park, CA.

A prominent proponent lays out areas where he agrees with critics, such as on the use of screening, but pushes back on the need to show ROI.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Ron Goetzel wears two hats. He is a senior scientist and director of the Institute for Health and Productivity Studies (IHPS) at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health and vice president of consulting and applied research for Truven Health Analytics.

With Congress not yet renewing TRIPRA, businesses should use risk models and contingency plans to gain access to alternative sources.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Duncan Ellis is a managing director resident in Marsh's New York office and is the leader of the U.S. property practice. Ellis oversees approximately 250 brokers handling in excess of 3,500 clients and $3 billion in premium. He is also directly involved in many of the country’s larger global risk management clients, as well as many of the smaller middle market accounts.

Despite the hype, they won't want to take on the full role of insurers.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Barry Rabkin is a technology-focused insurance industry analyst. His research focuses on areas where current and emerging technology affects insurance commerce, markets, customers and channels. He has been involved with the insurance industry for more than 35 years.

Businesses have adopted social media, but in 2015 it will no longer be seen as a discrete activity; it will spread through the whole organization.

Above: Starbucks' Tweet A Coffee campaign on Twitter.

Below: Burberry connecting with its audience on Instagram.

Above: Starbucks' Tweet A Coffee campaign on Twitter.

Below: Burberry connecting with its audience on Instagram.

Even in financial services, an industry sometimes perceived as slow and sluggish because of the regulatory environment, the world’s largest banks, insurers and financial firms are “getting social.” At Hearsay Social, we now support more than 100,000 financial professionals, allowing them to meaningfully connect with clients and prospects across multiple social networks and devices.

Whether it’s improved responsiveness to customer complaints, greater audience reach, more instantaneous market insight or the opportunity to connect with a new lead, compelling business cases now abound on social media.

In most organizations, however, social media still sits in a silo by itself. And some companies are still investing in social just to say they are social. Therefore, my big idea for 2015 is that social media will cease to exist as an individual silo, but instead will become integrated into standard business practice.

With the initial business case proven, it is time for the C-suite as well as functional leaders to institutionalize social as a core part of how business is done every day. Here’s how:

Define a customer-centered vision for transformation

We like to think we’ve come so far, but change comes from the top. And how much can be said when, in 2014, two in three CEOs still have no social presence on any major social network whatsoever? (Source: 2014 Social CEO Report, CEO.com.) Of those CEOs who do use social media, two in three are only on one platform. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the only Fortune 500 CEO on every major social network is Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, who is arguably the best-equipped to understand the power of social.

Even in financial services, an industry sometimes perceived as slow and sluggish because of the regulatory environment, the world’s largest banks, insurers and financial firms are “getting social.” At Hearsay Social, we now support more than 100,000 financial professionals, allowing them to meaningfully connect with clients and prospects across multiple social networks and devices.

Whether it’s improved responsiveness to customer complaints, greater audience reach, more instantaneous market insight or the opportunity to connect with a new lead, compelling business cases now abound on social media.

In most organizations, however, social media still sits in a silo by itself. And some companies are still investing in social just to say they are social. Therefore, my big idea for 2015 is that social media will cease to exist as an individual silo, but instead will become integrated into standard business practice.

With the initial business case proven, it is time for the C-suite as well as functional leaders to institutionalize social as a core part of how business is done every day. Here’s how:

Define a customer-centered vision for transformation

We like to think we’ve come so far, but change comes from the top. And how much can be said when, in 2014, two in three CEOs still have no social presence on any major social network whatsoever? (Source: 2014 Social CEO Report, CEO.com.) Of those CEOs who do use social media, two in three are only on one platform. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the only Fortune 500 CEO on every major social network is Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, who is arguably the best-equipped to understand the power of social.

We need to change this next year. If you truly want to create a customer-centered organization -- that is, a company dedicated to long-term success amid seismic shifts in consumer expectations and behavior -- then executives at the top must articulate why the transformation needs to take place. The first step toward articulating this is leading by example: CEOs, functional and line-of-business heads and first-line managers all need to be practicing what they preach so that they are not only more credible but are also better-equipped to lead and influence from within their organizations.

Create a new methodology, process, and metrics

It’s no longer acceptable to be doing social media for the sake of doing it. Have a plan in place, no matter how simple. Document your plan and intended goals, train employees and managers on it, drive success by checking in regularly and, of course, measure people on it.

Our customer success team at Hearsay Social, for example, has developed a four-step methodology for financial firms and their advisers who may initially feel overwhelmed when approaching social: First, establish a presence, which can be measured simply by seeing who has online social profiles. Second, grow your network by connecting with colleagues and clients where appropriate -- yet another step that can be easily measured. Next, listen to your network for opportunities that could help you grow your business. Finally, share content and thought leadership to continually stay top-of-mind with your audience.

We need to change this next year. If you truly want to create a customer-centered organization -- that is, a company dedicated to long-term success amid seismic shifts in consumer expectations and behavior -- then executives at the top must articulate why the transformation needs to take place. The first step toward articulating this is leading by example: CEOs, functional and line-of-business heads and first-line managers all need to be practicing what they preach so that they are not only more credible but are also better-equipped to lead and influence from within their organizations.

Create a new methodology, process, and metrics

It’s no longer acceptable to be doing social media for the sake of doing it. Have a plan in place, no matter how simple. Document your plan and intended goals, train employees and managers on it, drive success by checking in regularly and, of course, measure people on it.

Our customer success team at Hearsay Social, for example, has developed a four-step methodology for financial firms and their advisers who may initially feel overwhelmed when approaching social: First, establish a presence, which can be measured simply by seeing who has online social profiles. Second, grow your network by connecting with colleagues and clients where appropriate -- yet another step that can be easily measured. Next, listen to your network for opportunities that could help you grow your business. Finally, share content and thought leadership to continually stay top-of-mind with your audience.

Four steps to successful social business: Establish a presence, grow your network, listen to your network ("Hear") and share content ("Say").

Having a methodology, process and metrics in place for the social program helps institutionalize social as part of a company’s DNA and standard operating procedure while ensuring repeatability and scale as the company brings on new employees.

Cut and consolidate

Regardless of the organization, resources are never unlimited. Employees can only get so much done in a day, and there’s only so much cash flowing to fuel projects.

With that in mind, even the largest companies in the world must start thinking like start-ups by adopting a mentality of ruthless focus. In other words, you need to decide what you’re not going to do to make room for social.

For example, many of the insurance agencies we power on social media have decided to stop advertising on park benches and in the Yellow Pages. Instead, they are using their funds to buy promoted posts on Facebook. Another company, a financial services firm, which previously provided two separate training programs for “inter-generational wealth transfer” and “social media,” realized that there was actually an opportunity to combine the two because social media should be core to any effort to appeal to future generations of heirs.

Let your people teach and inspire one another

The first three steps are all top-down, but equally important, if not more so, is the groundswell of employee engagement and feeling of ownership. Companies more than ever need to have bottoms-up evangelism and peer-to-peer sharing to succeed in the digital era.

As partners of our client companies, we regularly attend national conferences hosted by our client organizations that bring together advisers across the country to share ideas about how they do business today. Time and time again, we hear anecdotes of social-savvy advisers sharing their success stories and ROI proof points, which serve to sway even the most skeptical advisers to become social media believers and practitioners. In the end, though executive buy-in is crucial, peer-to-peer evangelism will be much more credible than corporate departments pushing their initiatives down. You need both.

Expect continual iteration

Four steps to successful social business: Establish a presence, grow your network, listen to your network ("Hear") and share content ("Say").

Having a methodology, process and metrics in place for the social program helps institutionalize social as part of a company’s DNA and standard operating procedure while ensuring repeatability and scale as the company brings on new employees.

Cut and consolidate

Regardless of the organization, resources are never unlimited. Employees can only get so much done in a day, and there’s only so much cash flowing to fuel projects.

With that in mind, even the largest companies in the world must start thinking like start-ups by adopting a mentality of ruthless focus. In other words, you need to decide what you’re not going to do to make room for social.

For example, many of the insurance agencies we power on social media have decided to stop advertising on park benches and in the Yellow Pages. Instead, they are using their funds to buy promoted posts on Facebook. Another company, a financial services firm, which previously provided two separate training programs for “inter-generational wealth transfer” and “social media,” realized that there was actually an opportunity to combine the two because social media should be core to any effort to appeal to future generations of heirs.

Let your people teach and inspire one another

The first three steps are all top-down, but equally important, if not more so, is the groundswell of employee engagement and feeling of ownership. Companies more than ever need to have bottoms-up evangelism and peer-to-peer sharing to succeed in the digital era.

As partners of our client companies, we regularly attend national conferences hosted by our client organizations that bring together advisers across the country to share ideas about how they do business today. Time and time again, we hear anecdotes of social-savvy advisers sharing their success stories and ROI proof points, which serve to sway even the most skeptical advisers to become social media believers and practitioners. In the end, though executive buy-in is crucial, peer-to-peer evangelism will be much more credible than corporate departments pushing their initiatives down. You need both.

Expect continual iteration

To succeed as a company in 2015 and beyond, it is imperative to accept that change is ubiquitous and accelerating. There’s new tech coming out every day -- from mobile payments to virtual reality, connected cars and homes to the Internet of Everything -- destined to challenge and upend every established sector. In turn, each of these disruptions will cause even newer technologies like social media to evolve, and there will always be new use cases. Perhaps your company may pave the way to the next innovation in social media case studies.

In 2015, social will be disrupted by going mainstream across the enterprise. Soon, we will no longer call it out separately. Social as a silo is going away. A decade ago, we spent a lot of breath talking about “online” experiences, but today we assume every customer is always online. Social will be the same.

To succeed as a company in 2015 and beyond, it is imperative to accept that change is ubiquitous and accelerating. There’s new tech coming out every day -- from mobile payments to virtual reality, connected cars and homes to the Internet of Everything -- destined to challenge and upend every established sector. In turn, each of these disruptions will cause even newer technologies like social media to evolve, and there will always be new use cases. Perhaps your company may pave the way to the next innovation in social media case studies.

In 2015, social will be disrupted by going mainstream across the enterprise. Soon, we will no longer call it out separately. Social as a silo is going away. A decade ago, we spent a lot of breath talking about “online” experiences, but today we assume every customer is always online. Social will be the same.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Clara Shih is CEO and founder of Hearsay Social and a pioneer in the social media industry. Hearsay Social is the leading social sales and marketing platform, empowering the world's largest companies to build stronger customer relationships. Clara is a member of the Starbucks board and previously served in a variety of technical, product and marketing roles at Google, Microsoft and Salesforce.com.

The resulting confusion can hurt employees and raise costs for employers.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Teddy Snyder mediates workers' compensation cases throughout California through WCMediator.com. An attorney since 1977, she has concentrated on claim settlement for more than 19 years. Her motto is, "Stop fooling around and just settle the case."

The question must be addressed if we are to get the maximum health for the population as a whole based on all the money we spend.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

John C. Goodman is one of the nation’s leading thinkers on health policy. He is a senior fellow at the Independent Institute and author of the widely acclaimed book, <em>Priceless: Curing the Healthcare Crisis</em>. The Wall Street Journal calls Dr. Goodman "the father of health savings accounts." He has written numerous editorials in the Wall Street Journal, USA Today, Investor's Business Daily, Los Angeles Times and many other publications.