We thank Ron Goetzel, representing Truven Health and Johns Hopkins, for posting on Insurance Thought Leadership a

rebuttal to our

viral November posting, "

Workplace Wellness Shows No Savings." Paradoxically, while he conceived and produced the posting, we are happy to publicize it for him. If you’ve heard that song before, think Mike Dukakis’s tank ride during his disastrous 1988 presidential campaign.

Goetzel's rebuttal, “

The Value of Workplace Wellness Programs,” raises at least 11 questions that he has been declining to answer. We hope he will respond here on ITL. And, of course, we are happy to answer any specific questions he would ask us, as we think we are already doing in the case of the point he raises about wellness-sensitive medical events. (We offer, for the third time, to have a straight-up debate and hope that he reconsiders his previous refusals.)

Ron:

(1) How can you say you are not familiar with measuring wellness-sensitive medical events (WSMEs), like heart attacks? Your exact words are: “What are these events? Where have they been published? Who has peer-reviewed them?” Didn’t you yourself just

review an article on that very topic, a study that we ourselves had

hyperlinked as an example of peer-reviewed WSMEs in the exact article of ours that you are rebutting now? WSMEs are the events that should decline because of a wellness program. Example: If you institute a wellness program aimed at avoiding heart attacks, you’d measure the change in the number of heart attacks across your population as a “plausibility test” to see if the program worked, just like you’d measure the impact of a campaign to avoid teenage pregnancies by observing the change in the rate of teenage pregnancies. We're not sure why you think that simple concept of testing plausibility using WSMEs needs peer review. Indeed, we don’t know how else one would measure impact of either program, which is why the esteemed

Validation Institute recognizes only that methodology. (In any event, you did already review WMSEs in your own article.) We certainly concur with your related view that randomized controlled trials are impractical in workplace settings (and can’t blame you for avoiding them, given that your colleague Michael O’Donnell’s journal published a meta-analysis showing RCTs have

negative ROIs).

(2) How do you reconcile your role as Highmark’s consultant

for the

notoriously humiliating, unpopular and counterproductive Penn State wellness program with your current position that employees need to be treated with “respect and dignity”? Exactly what about Penn State’s required monthly testicle check and $1,200 fine on female employees for not disclosing their pregnancy plans respected the dignity of employees?

(3) Which of your programs adhere to U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (

USPSTF) screening guidelines and intervals that you now claim to embrace? Once again, we cite the Penn State example, because it is in the public domain -- almost nothing about that program was USPSTF-compliant, starting with the aforementioned

testicle checks.

(4) Your posting mentions “peer review” nine times. If peer review is so important to wellness true believers, how come none of your colleagues editing the three wellness promotional journals (

JOEM,

AJPM and

AJHP) has ever asked either of us to peer-review a single article, despite the fact that we’ve amply demonstrated our prowess at peer review by exposing two dozen fraudulent claims on

They Said What?, including exposés of four companies represented on your Koop Award committee (

Staywell, Mercer, Milliman and

Wellsteps) along with three fraudulent claims in

Koop Award-winning programs?

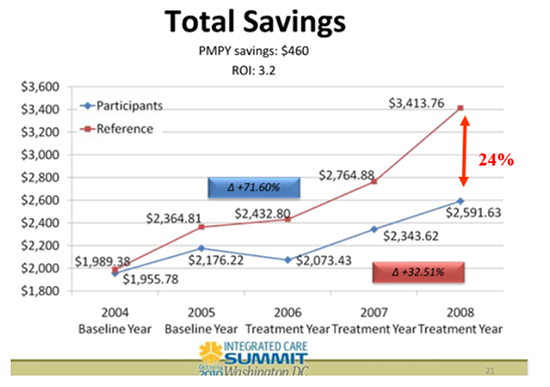

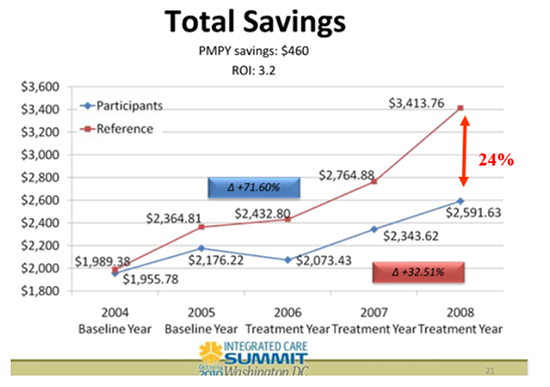

(5) Perhaps the most popular slide used in support of wellness-industry ROI actually shows the reverse -- that motivation, rather than the wellness programs themselves, drives the health spending differential between participants and non-participants. How do we know that? Because on that Eastman Chemical-Health Fitness Corp. slide (reproduced below), significant savings accrued and were counted for 2005 –

the year before the wellness program was implemented. Now you say 2005 was “unfortunately mislabeled” on that slide. Unless this mislabeling was an act of God, please use the active voice: Who mislabeled this slide for five years; where is the person's apology; and why didn’t any of the

analytical luminaries on your committee disclose this mislabeling even after they

knew it was mislabeled? The problem was noted in both

Surviving Workplace Wellness and the trade-bestselling,

award-winning Why Nobody Believes the Numbers, which we know you’ve read because you copied pages from it before Wiley & Sons demanded you stop? Was it because

HFC sponsors your committee, or was it because Koop Committee members lack the basic error identification skills taught in

courses on

outcomes analysis that no committee member has ever passed?

(6) Why doesn’t anyone on the Koop Committee notice any of these “unfortunate mislabelings” until several years after we point out that they are in plain view?

(7) Why is it that every time HFC admits lying, the penalty that you assess -- as president of the Koop Award Committee -- is to anoint their programs as “best practices” in health promotion? (See Eastman Chemical and Nebraska in the list below.) Doesn’t that send a signal that Dr. Koop might have objected to?

(8) Whenever HFC publishes lengthy press releases announcing that its customers received the “prestigious” Koop Award, it always forgets to mention that it sponsors the awards. With your post’s emphasis on “the spirit of full disclosure” and “transparency,” why haven’t you insisted HFC disclose that it finances the award (sort of like when Nero used to win the Olympics because he ran them)?

(9) Speaking of “best practices” and Koop Award winners, HFC’s admitted lies about saving the lives of 514

cancer victims in its award-winning Nebraska program are technically a violation of the state’s anti-fraud statute, because HFC accepted state money and then misrepresented outcomes. Which is it: Is HFC a best practice, or should it be prosecuted for fraud?

(10) RAND Corp.’s wellness guru Soeren Mattke, who also disputes

wellness ROIs, has

observed that every time one of the wellness industry’s unsupportable claims gets disproven, wellness defenders say they didn’t really mean it, and they really meant something else altogether. Isn’t this exactly what you are doing here, with the “mislabeled” slide, with your sudden epiphany about following USPSTF guidelines and respecting employee dignity and with your new position that ROI doesn’t matter any more, now that most ROI claims have been invalidated?

(11) Why are you still quoting Katherine Baicker’s five-year-old meta-analysis claiming 3.27-to-1 savings from wellness in (roughly) 16-year-old studies, even though you must be fully aware that she herself has

repeatedly disowned it and now

says: “There are very few studies that have reliable data on the costs and benefits”? We have offered to

compliment wellness defenders for telling the truth in every instance in which they acknowledge all her backpedaling whenever they cite her study. We look forward to being able to compliment you on truthfulness when you admit this. This offer, if you accept it, is an improvement over our current

Groundhog Day-type cycle where you

cite her study, we

point out that she’s walked it back four times, and you somehow never notice her recantations and then continue to cite the meta-analysis as though it’s beyond reproach.

To end on a positive note, while we see many differences between your words and your deeds, let us give you the benefit of the doubt and assume you mean what you say and not what you do. In that case, we invite you to join us in writing an open letter to Penn State, the Business Roundtable, Honeywell, Highmark and every other organization (including

Vik Khanna’s wife’s employer) that forces employees to choose between forfeiting large sums of money and maintaining their dignity and privacy. We could collectively advise them to do exactly what you now say: Instead of playing doctor with “pry, poke, prod and punish” programs, we would encourage employers to adhere to USPSTF screening guidelines and frequencies and otherwise stay out of employees’ personal medical affairs unless they ask for help, because overdoctoring produces neither positive ROIs nor even healthier employers. And we need to emphasize that it’s OK if there is no ROI because ROI doesn’t matter.

As a gesture to mend fences, we will offer a 50% discount to all Koop Committee members for the

Critical Outcomes Report Analysis course and certification, which is also recognized by the Validation Institute. This course will help your committee members learn how to avoid the embarrassing mistakes they consistently otherwise make and (assuming you institute conflict-of-interest rules as well to require disclosure of sponsorships) ensure that worthy candidates win your awards.

Photo credit: Christopher Conover, Duke University

Photo credit: Christopher Conover, Duke University