Environmental: Reshaping Catastrophe Risks and Insured Values

Catastrophe losses have soared since the 1970s. While 2014 had the largest number of events over the course of the past 30 years, losses and fatalities were actually below average. Globally, the use of technology, availability of data and ability to locate and respond to disaster in near real-time is helping to manage losses and save lives, though there are predictions that potential economic losses will be 160% higher in 2030 than they were in 1980.

Shifts in global production and supply are leading to a sharp rise in value at risk (VaR) in under-insured territories; the $12 billion of losses from the Thai floods of 2011 exemplify this. A 2013 report by the UN International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) and PwC concluded that multinationals’ dependencies on unstable international supply chains now pose a systemic risk to "business as usual."

Environmental measures to mitigate risk

Moves to mitigate catastrophe risks

and control losses are increasing. Organizations, governments and UN bodies are working more closely to share information on the impact of disaster risk. Examples include R!SE, a joint UN-PwC initiative, which looks at how to embed disaster risk management into corporate strategy and investment decisions.

Governments also are starting to develop plans and policies for addressing climatic instability, though for the most part policy actions remain unpredictable, inconsistent and reactive.

Developments in risk modeling

A new generation of catastrophe models is ushering in a transformational expansion in both geographical

breadth and underwriting applications. Until recently, cat models primarily concentrated on developed market peak zones (such as Florida windstorm). As the unexpectedly high insurance losses from the 2010 Chilean earthquake and the 2011 Thai floods highlight, this narrow focus has failed to take account of the surge in production and asset values in fast-growth SAAAME markets (South America, Africa, Asia and the Middle East). The new models cover many of these previously non-modeled zones.

The other big difference for insurers is their newfound ability to plug different analytics into a single platform. This offers the advantages of being able to understand where there may be pockets of untapped capacity or, conversely, hazardous concentrations. The result is much more closely targeted risk selection and pricing.

The challenge is how to build these models into the running of the business. Cat modeling has traditionally been the preserve of a small, specialized team. The new capabilities are supposed to be easier to use and hence open to a much wider array of business, IT and analytical teams. It’s important to determine the kind of talent needed

to make best use of these systems, as well as how they will change the way underwriting decisions are made.

Emerging developments include new monitoring and detection systems, which draw

on multiple fixed and drone sensors.

Challenges for evaluating and pricing risk

Beyond catastrophe risks are disruptions to asset/insured values resulting from constraints on water, land and other previously under-evaluated risk factors. There are already examples of industrial plants that have had to close because of limited access to water.

Economic: Adapting to a Multipolar World

Struggling to sustain margins

The challenging economic climate has

held back discretionary spending on life, annuities and pensions, with the impact being compounded by low interest rates and the resulting difficulties in sustaining competitive returns for policyholders. The keys to sustaining margins are likely to be simple, low-cost, digitally distributed products for the mass market and use of the latest risk analytics to help offer guarantees at competitive prices.

The challenges facing P&C insurers center on low investment returns and a softening market. Opportunities to seek out new customers and boost revenues include strategic alliances. Examples could include affinity groups, manufacturers or major retailers. A further possibility is that one of the telecoms or Internet giants will want a tie-up with an insurer to help it move into the market.

More than 30% of insurance CEOs

now see alliances as an opportunity to strengthen innovation. Examples include the partnership between a leading global reinsurer and software group, which aims to provide more advanced cyber risk protection for corporations.

Surprisingly, only 10% of insurance CEOs are looking to partner with start- ups, even though such alliances could provide valuable access to the new ideas and technologies they need.

SAAAME growth

Growth in SAAAME insurance markets will continue to vary. Slowing growth

in some major markets, notably Brazil, could hold back expansion. In others, notably India, we are actually seeing a decline in life, annuity and pension take-up as a result of the curbs on commissions for unit-linked insurance plans (ULIP). Further development in capital markets will be necessary to encourage savers to switch their deposits to insurance products.

As the reliance on agency channels adds to costs, there are valuable opportunities to offer cost- effective digital distribution. Successful models of inclusion include an Indian national health insurance program, which is aimed at poorer households and operates through a public/private partnership. More than 30 million households have taken up the smart cards that provide them with access to hospital treatment.

The already strong growth (10% a year) in micro-insurance is also set to increase, drawing on models developed within micro-credit. The challenge for insurers is the need to make products that are sufficiently affordable and comprehensible to consumers who have little or no familiarity with the concept of insurance.

Rather than waiting for a market-wide alignment of data and pricing, some insurers have moved people onto the ground to build up the necessary data sets, often working in partnership with governments, regional and local development authorities and banks and local business groups.

Urbanization

The urban/rural divide may actually be more relevant to growth opportunities ahead than the emerging/developed market divide. In 1800, barely one in 50 people lived in cities. By 2009, urban dwellers had become a majority of the global population for the first time. Now, every week, 1.5 million people are added to the urban population, the bulk of them in SAAAME markets.

Cities are the main engines of the global economy, with 50% of global GDP generated in the world’s 300 largest metropolitan areas. The result is more wealth to protect. Infrastructure development alone will generate an estimated $68 billion in premium income between now and 2030. Urban citizens will be more likely to be exposed to insurance products and have access to them. Urbanization is also likely to increase purchases of life, annuities and pensions’ products, as people migrating into cities have to make individual provision for the future rather than relying on extended family support.

Yet as the size and number of mega-metropolises grow, so does the concentration of risk. Key areas of exposure go beyond property and catastrophe coverage to include the impact of air pollution and poor water quality and sanitation on health.

Tackling under-insurance

A Lloyd’s report comparing the level

of insurance penetration and natural catastrophe losses in countries around the world found that 17 fast-growth markets had an annualized insurance deficit of $168 billion, creating threats to sustained economic growth and the ability to recover from disasters.

Political: Harmonization, Standardization and Globalization of the Insurance Market

Government in the tent

At a time when all financial services businesses face considerable scrutiny, strengthening the social mandate through closer alignment with government goals could give insurers greater freedom. Insurers also could be in a stronger position to attract quality talent at a time when many of the brightest candidates are looking for more meaning from their chosen careers.

Government and insurers can join forces in the development of effective retirement and healthcare solutions (although there are risks). Further opportunities include a risk partnership approach to managing exposures that neither insurers nor governments have either the depth of data or financial resources to cover on their own, notably cyber, terrorism and catastrophe risks.

Impact of regulation

Insurers have never had to deal with an all-encompassing set of global prudential regulations comparable to the Basel Accords governing banks. But this is what the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and its sponsors in the G20 now want to see as the baseline requirements for not just the global insurers designated as systemically risky, but also a tier of internationally active insurance groups.

The G20’s focus on insurance regulation highlights the heightened politicization of financial services. Governments want to make sure that taxpayers no longer have to bail out failing financial institutions. The result

is an overhaul of capital requirements

in many parts of the world and a new basic capital requirement for G-SIIs. The other game-changing development is the emergence of a new breed of cross-state/cross-border regulator, which has been set up to strengthen co-ordination of supervision, crisis management and other key topics. These include the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) and the Federal Insurance Office (FIO) in the U.S.

Dealing with these developments requires a mechanism capable of looking beyond basic operational compliance at how new regulation will affect the strategy and structure of the organization and using this assessment to develop a clear and coherent company-wide response.

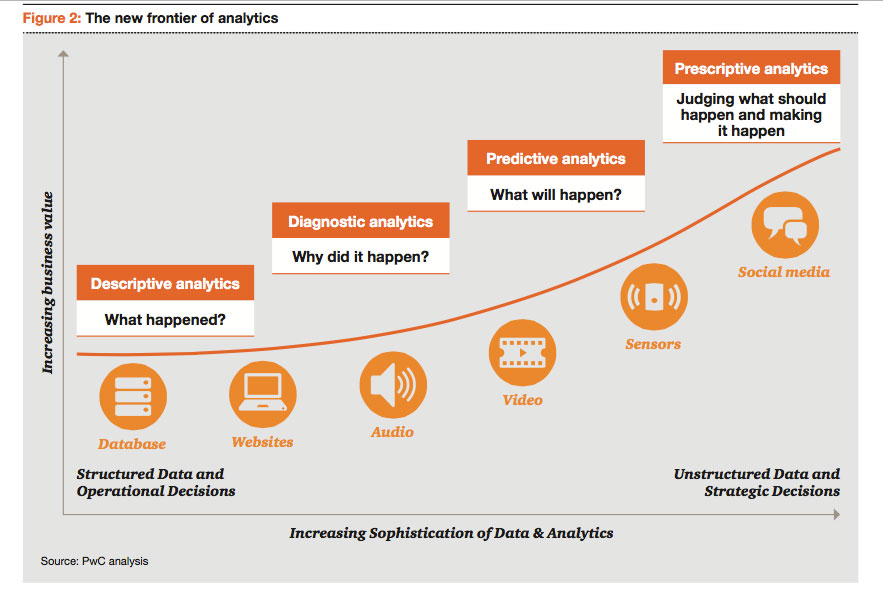

Technology will allow risk to be analyzed in real time, and predictive models would enable supervisors to identify and home in on areas in need

of intervention. Regulators would also be able to tap into the surge in data and analysis within supervised organizations, creating the foundations for machine-to-machine regulation.

A more unstable world

From the crisis in Ukraine to the rise of ISIS, instability is a fact of life. Pressure on land and water, as well as oil and minerals, is intensifying competition for strategic resources and potentially bringing states into conflict. The ways these disputes are playing out is also impinging on corporations to an ever-greater extent, be this trade sanctions or state-directed cyber-attacks.

Businesses, governments and individuals also need to understand the potential causes of conflict and their ramifications and develop appropriate contingency planning and response. At the very least, insurers should seek to model these threats and bring them into their overall risk evaluations. For some, this will be an important element of their growing role as risk advisers and mitigators. Investment firms are beginning to hire ex-intelligence and military figures as advisers or calling in dedicated political consultancies as part of their strategic planning. More insurers are likely to follow suit.

The final article in this series will look at scenarios that could play out for insurers and will lay out a way to formulate an effective strategy. If you want a copy of the report from which these articles are excerpted, click here.

Environmental: Reshaping Catastrophe Risks and Insured Values

Catastrophe losses have soared since the 1970s. While 2014 had the largest number of events over the course of the past 30 years, losses and fatalities were actually below average. Globally, the use of technology, availability of data and ability to locate and respond to disaster in near real-time is helping to manage losses and save lives, though there are predictions that potential economic losses will be 160% higher in 2030 than they were in 1980.

Shifts in global production and supply are leading to a sharp rise in value at risk (VaR) in under-insured territories; the $12 billion of losses from the Thai floods of 2011 exemplify this. A 2013 report by the UN International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) and PwC concluded that multinationals’ dependencies on unstable international supply chains now pose a systemic risk to "business as usual."

Environmental measures to mitigate risk

Moves to mitigate catastrophe risks

and control losses are increasing. Organizations, governments and UN bodies are working more closely to share information on the impact of disaster risk. Examples include R!SE, a joint UN-PwC initiative, which looks at how to embed disaster risk management into corporate strategy and investment decisions.

Governments also are starting to develop plans and policies for addressing climatic instability, though for the most part policy actions remain unpredictable, inconsistent and reactive.

Developments in risk modeling

A new generation of catastrophe models is ushering in a transformational expansion in both geographical

breadth and underwriting applications. Until recently, cat models primarily concentrated on developed market peak zones (such as Florida windstorm). As the unexpectedly high insurance losses from the 2010 Chilean earthquake and the 2011 Thai floods highlight, this narrow focus has failed to take account of the surge in production and asset values in fast-growth SAAAME markets (South America, Africa, Asia and the Middle East). The new models cover many of these previously non-modeled zones.

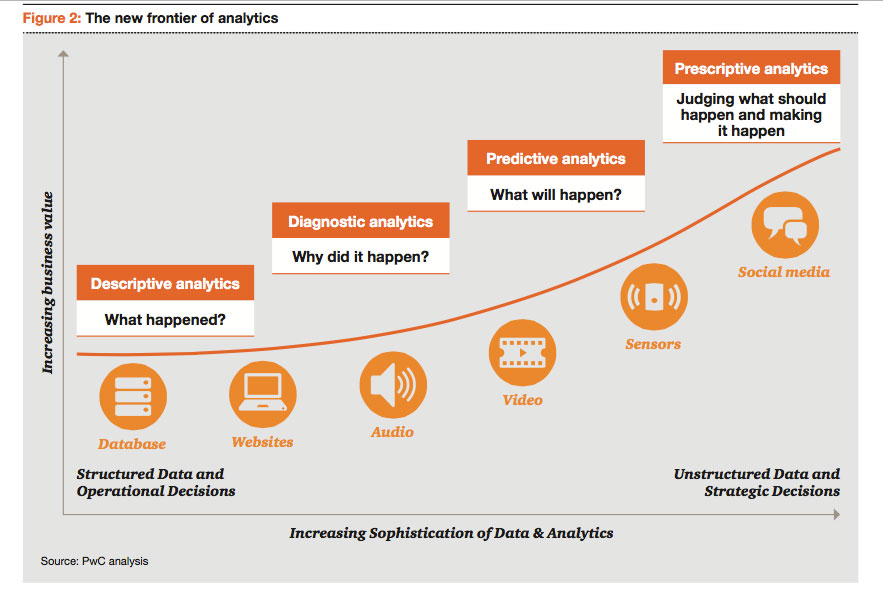

The other big difference for insurers is their newfound ability to plug different analytics into a single platform. This offers the advantages of being able to understand where there may be pockets of untapped capacity or, conversely, hazardous concentrations. The result is much more closely targeted risk selection and pricing.

The challenge is how to build these models into the running of the business. Cat modeling has traditionally been the preserve of a small, specialized team. The new capabilities are supposed to be easier to use and hence open to a much wider array of business, IT and analytical teams. It’s important to determine the kind of talent needed

to make best use of these systems, as well as how they will change the way underwriting decisions are made.

Emerging developments include new monitoring and detection systems, which draw

on multiple fixed and drone sensors.

Challenges for evaluating and pricing risk

Beyond catastrophe risks are disruptions to asset/insured values resulting from constraints on water, land and other previously under-evaluated risk factors. There are already examples of industrial plants that have had to close because of limited access to water.

Economic: Adapting to a Multipolar World

Struggling to sustain margins

The challenging economic climate has

held back discretionary spending on life, annuities and pensions, with the impact being compounded by low interest rates and the resulting difficulties in sustaining competitive returns for policyholders. The keys to sustaining margins are likely to be simple, low-cost, digitally distributed products for the mass market and use of the latest risk analytics to help offer guarantees at competitive prices.

The challenges facing P&C insurers center on low investment returns and a softening market. Opportunities to seek out new customers and boost revenues include strategic alliances. Examples could include affinity groups, manufacturers or major retailers. A further possibility is that one of the telecoms or Internet giants will want a tie-up with an insurer to help it move into the market.

More than 30% of insurance CEOs

now see alliances as an opportunity to strengthen innovation. Examples include the partnership between a leading global reinsurer and software group, which aims to provide more advanced cyber risk protection for corporations.

Surprisingly, only 10% of insurance CEOs are looking to partner with start- ups, even though such alliances could provide valuable access to the new ideas and technologies they need.

SAAAME growth

Growth in SAAAME insurance markets will continue to vary. Slowing growth

in some major markets, notably Brazil, could hold back expansion. In others, notably India, we are actually seeing a decline in life, annuity and pension take-up as a result of the curbs on commissions for unit-linked insurance plans (ULIP). Further development in capital markets will be necessary to encourage savers to switch their deposits to insurance products.

As the reliance on agency channels adds to costs, there are valuable opportunities to offer cost- effective digital distribution. Successful models of inclusion include an Indian national health insurance program, which is aimed at poorer households and operates through a public/private partnership. More than 30 million households have taken up the smart cards that provide them with access to hospital treatment.

The already strong growth (10% a year) in micro-insurance is also set to increase, drawing on models developed within micro-credit. The challenge for insurers is the need to make products that are sufficiently affordable and comprehensible to consumers who have little or no familiarity with the concept of insurance.

Rather than waiting for a market-wide alignment of data and pricing, some insurers have moved people onto the ground to build up the necessary data sets, often working in partnership with governments, regional and local development authorities and banks and local business groups.

Urbanization

The urban/rural divide may actually be more relevant to growth opportunities ahead than the emerging/developed market divide. In 1800, barely one in 50 people lived in cities. By 2009, urban dwellers had become a majority of the global population for the first time. Now, every week, 1.5 million people are added to the urban population, the bulk of them in SAAAME markets.

Cities are the main engines of the global economy, with 50% of global GDP generated in the world’s 300 largest metropolitan areas. The result is more wealth to protect. Infrastructure development alone will generate an estimated $68 billion in premium income between now and 2030. Urban citizens will be more likely to be exposed to insurance products and have access to them. Urbanization is also likely to increase purchases of life, annuities and pensions’ products, as people migrating into cities have to make individual provision for the future rather than relying on extended family support.

Yet as the size and number of mega-metropolises grow, so does the concentration of risk. Key areas of exposure go beyond property and catastrophe coverage to include the impact of air pollution and poor water quality and sanitation on health.

Tackling under-insurance

A Lloyd’s report comparing the level

of insurance penetration and natural catastrophe losses in countries around the world found that 17 fast-growth markets had an annualized insurance deficit of $168 billion, creating threats to sustained economic growth and the ability to recover from disasters.

Political: Harmonization, Standardization and Globalization of the Insurance Market

Government in the tent

At a time when all financial services businesses face considerable scrutiny, strengthening the social mandate through closer alignment with government goals could give insurers greater freedom. Insurers also could be in a stronger position to attract quality talent at a time when many of the brightest candidates are looking for more meaning from their chosen careers.

Government and insurers can join forces in the development of effective retirement and healthcare solutions (although there are risks). Further opportunities include a risk partnership approach to managing exposures that neither insurers nor governments have either the depth of data or financial resources to cover on their own, notably cyber, terrorism and catastrophe risks.

Impact of regulation

Insurers have never had to deal with an all-encompassing set of global prudential regulations comparable to the Basel Accords governing banks. But this is what the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and its sponsors in the G20 now want to see as the baseline requirements for not just the global insurers designated as systemically risky, but also a tier of internationally active insurance groups.

The G20’s focus on insurance regulation highlights the heightened politicization of financial services. Governments want to make sure that taxpayers no longer have to bail out failing financial institutions. The result

is an overhaul of capital requirements

in many parts of the world and a new basic capital requirement for G-SIIs. The other game-changing development is the emergence of a new breed of cross-state/cross-border regulator, which has been set up to strengthen co-ordination of supervision, crisis management and other key topics. These include the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) and the Federal Insurance Office (FIO) in the U.S.

Dealing with these developments requires a mechanism capable of looking beyond basic operational compliance at how new regulation will affect the strategy and structure of the organization and using this assessment to develop a clear and coherent company-wide response.

Technology will allow risk to be analyzed in real time, and predictive models would enable supervisors to identify and home in on areas in need

of intervention. Regulators would also be able to tap into the surge in data and analysis within supervised organizations, creating the foundations for machine-to-machine regulation.

A more unstable world

From the crisis in Ukraine to the rise of ISIS, instability is a fact of life. Pressure on land and water, as well as oil and minerals, is intensifying competition for strategic resources and potentially bringing states into conflict. The ways these disputes are playing out is also impinging on corporations to an ever-greater extent, be this trade sanctions or state-directed cyber-attacks.

Businesses, governments and individuals also need to understand the potential causes of conflict and their ramifications and develop appropriate contingency planning and response. At the very least, insurers should seek to model these threats and bring them into their overall risk evaluations. For some, this will be an important element of their growing role as risk advisers and mitigators. Investment firms are beginning to hire ex-intelligence and military figures as advisers or calling in dedicated political consultancies as part of their strategic planning. More insurers are likely to follow suit.

The final article in this series will look at scenarios that could play out for insurers and will lay out a way to formulate an effective strategy. If you want a copy of the report from which these articles are excerpted, click here.Insurance at a Tipping Point (Part 2)

At the tipping point, here is a look at the five factors -- social, technological, environmental, economic and political -- that matter most.

Environmental: Reshaping Catastrophe Risks and Insured Values

Catastrophe losses have soared since the 1970s. While 2014 had the largest number of events over the course of the past 30 years, losses and fatalities were actually below average. Globally, the use of technology, availability of data and ability to locate and respond to disaster in near real-time is helping to manage losses and save lives, though there are predictions that potential economic losses will be 160% higher in 2030 than they were in 1980.

Shifts in global production and supply are leading to a sharp rise in value at risk (VaR) in under-insured territories; the $12 billion of losses from the Thai floods of 2011 exemplify this. A 2013 report by the UN International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) and PwC concluded that multinationals’ dependencies on unstable international supply chains now pose a systemic risk to "business as usual."

Environmental measures to mitigate risk

Moves to mitigate catastrophe risks

and control losses are increasing. Organizations, governments and UN bodies are working more closely to share information on the impact of disaster risk. Examples include R!SE, a joint UN-PwC initiative, which looks at how to embed disaster risk management into corporate strategy and investment decisions.

Governments also are starting to develop plans and policies for addressing climatic instability, though for the most part policy actions remain unpredictable, inconsistent and reactive.

Developments in risk modeling

A new generation of catastrophe models is ushering in a transformational expansion in both geographical

breadth and underwriting applications. Until recently, cat models primarily concentrated on developed market peak zones (such as Florida windstorm). As the unexpectedly high insurance losses from the 2010 Chilean earthquake and the 2011 Thai floods highlight, this narrow focus has failed to take account of the surge in production and asset values in fast-growth SAAAME markets (South America, Africa, Asia and the Middle East). The new models cover many of these previously non-modeled zones.

The other big difference for insurers is their newfound ability to plug different analytics into a single platform. This offers the advantages of being able to understand where there may be pockets of untapped capacity or, conversely, hazardous concentrations. The result is much more closely targeted risk selection and pricing.

The challenge is how to build these models into the running of the business. Cat modeling has traditionally been the preserve of a small, specialized team. The new capabilities are supposed to be easier to use and hence open to a much wider array of business, IT and analytical teams. It’s important to determine the kind of talent needed

to make best use of these systems, as well as how they will change the way underwriting decisions are made.

Emerging developments include new monitoring and detection systems, which draw

on multiple fixed and drone sensors.

Challenges for evaluating and pricing risk

Beyond catastrophe risks are disruptions to asset/insured values resulting from constraints on water, land and other previously under-evaluated risk factors. There are already examples of industrial plants that have had to close because of limited access to water.

Economic: Adapting to a Multipolar World

Struggling to sustain margins

The challenging economic climate has

held back discretionary spending on life, annuities and pensions, with the impact being compounded by low interest rates and the resulting difficulties in sustaining competitive returns for policyholders. The keys to sustaining margins are likely to be simple, low-cost, digitally distributed products for the mass market and use of the latest risk analytics to help offer guarantees at competitive prices.

The challenges facing P&C insurers center on low investment returns and a softening market. Opportunities to seek out new customers and boost revenues include strategic alliances. Examples could include affinity groups, manufacturers or major retailers. A further possibility is that one of the telecoms or Internet giants will want a tie-up with an insurer to help it move into the market.

More than 30% of insurance CEOs

now see alliances as an opportunity to strengthen innovation. Examples include the partnership between a leading global reinsurer and software group, which aims to provide more advanced cyber risk protection for corporations.

Surprisingly, only 10% of insurance CEOs are looking to partner with start- ups, even though such alliances could provide valuable access to the new ideas and technologies they need.

SAAAME growth

Growth in SAAAME insurance markets will continue to vary. Slowing growth

in some major markets, notably Brazil, could hold back expansion. In others, notably India, we are actually seeing a decline in life, annuity and pension take-up as a result of the curbs on commissions for unit-linked insurance plans (ULIP). Further development in capital markets will be necessary to encourage savers to switch their deposits to insurance products.

As the reliance on agency channels adds to costs, there are valuable opportunities to offer cost- effective digital distribution. Successful models of inclusion include an Indian national health insurance program, which is aimed at poorer households and operates through a public/private partnership. More than 30 million households have taken up the smart cards that provide them with access to hospital treatment.

The already strong growth (10% a year) in micro-insurance is also set to increase, drawing on models developed within micro-credit. The challenge for insurers is the need to make products that are sufficiently affordable and comprehensible to consumers who have little or no familiarity with the concept of insurance.

Rather than waiting for a market-wide alignment of data and pricing, some insurers have moved people onto the ground to build up the necessary data sets, often working in partnership with governments, regional and local development authorities and banks and local business groups.

Urbanization

The urban/rural divide may actually be more relevant to growth opportunities ahead than the emerging/developed market divide. In 1800, barely one in 50 people lived in cities. By 2009, urban dwellers had become a majority of the global population for the first time. Now, every week, 1.5 million people are added to the urban population, the bulk of them in SAAAME markets.

Cities are the main engines of the global economy, with 50% of global GDP generated in the world’s 300 largest metropolitan areas. The result is more wealth to protect. Infrastructure development alone will generate an estimated $68 billion in premium income between now and 2030. Urban citizens will be more likely to be exposed to insurance products and have access to them. Urbanization is also likely to increase purchases of life, annuities and pensions’ products, as people migrating into cities have to make individual provision for the future rather than relying on extended family support.

Yet as the size and number of mega-metropolises grow, so does the concentration of risk. Key areas of exposure go beyond property and catastrophe coverage to include the impact of air pollution and poor water quality and sanitation on health.

Tackling under-insurance

A Lloyd’s report comparing the level

of insurance penetration and natural catastrophe losses in countries around the world found that 17 fast-growth markets had an annualized insurance deficit of $168 billion, creating threats to sustained economic growth and the ability to recover from disasters.

Political: Harmonization, Standardization and Globalization of the Insurance Market

Government in the tent

At a time when all financial services businesses face considerable scrutiny, strengthening the social mandate through closer alignment with government goals could give insurers greater freedom. Insurers also could be in a stronger position to attract quality talent at a time when many of the brightest candidates are looking for more meaning from their chosen careers.

Government and insurers can join forces in the development of effective retirement and healthcare solutions (although there are risks). Further opportunities include a risk partnership approach to managing exposures that neither insurers nor governments have either the depth of data or financial resources to cover on their own, notably cyber, terrorism and catastrophe risks.

Impact of regulation

Insurers have never had to deal with an all-encompassing set of global prudential regulations comparable to the Basel Accords governing banks. But this is what the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and its sponsors in the G20 now want to see as the baseline requirements for not just the global insurers designated as systemically risky, but also a tier of internationally active insurance groups.

The G20’s focus on insurance regulation highlights the heightened politicization of financial services. Governments want to make sure that taxpayers no longer have to bail out failing financial institutions. The result

is an overhaul of capital requirements

in many parts of the world and a new basic capital requirement for G-SIIs. The other game-changing development is the emergence of a new breed of cross-state/cross-border regulator, which has been set up to strengthen co-ordination of supervision, crisis management and other key topics. These include the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) and the Federal Insurance Office (FIO) in the U.S.

Dealing with these developments requires a mechanism capable of looking beyond basic operational compliance at how new regulation will affect the strategy and structure of the organization and using this assessment to develop a clear and coherent company-wide response.

Technology will allow risk to be analyzed in real time, and predictive models would enable supervisors to identify and home in on areas in need

of intervention. Regulators would also be able to tap into the surge in data and analysis within supervised organizations, creating the foundations for machine-to-machine regulation.

A more unstable world

From the crisis in Ukraine to the rise of ISIS, instability is a fact of life. Pressure on land and water, as well as oil and minerals, is intensifying competition for strategic resources and potentially bringing states into conflict. The ways these disputes are playing out is also impinging on corporations to an ever-greater extent, be this trade sanctions or state-directed cyber-attacks.

Businesses, governments and individuals also need to understand the potential causes of conflict and their ramifications and develop appropriate contingency planning and response. At the very least, insurers should seek to model these threats and bring them into their overall risk evaluations. For some, this will be an important element of their growing role as risk advisers and mitigators. Investment firms are beginning to hire ex-intelligence and military figures as advisers or calling in dedicated political consultancies as part of their strategic planning. More insurers are likely to follow suit.

The final article in this series will look at scenarios that could play out for insurers and will lay out a way to formulate an effective strategy. If you want a copy of the report from which these articles are excerpted, click here.

Environmental: Reshaping Catastrophe Risks and Insured Values

Catastrophe losses have soared since the 1970s. While 2014 had the largest number of events over the course of the past 30 years, losses and fatalities were actually below average. Globally, the use of technology, availability of data and ability to locate and respond to disaster in near real-time is helping to manage losses and save lives, though there are predictions that potential economic losses will be 160% higher in 2030 than they were in 1980.

Shifts in global production and supply are leading to a sharp rise in value at risk (VaR) in under-insured territories; the $12 billion of losses from the Thai floods of 2011 exemplify this. A 2013 report by the UN International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) and PwC concluded that multinationals’ dependencies on unstable international supply chains now pose a systemic risk to "business as usual."

Environmental measures to mitigate risk

Moves to mitigate catastrophe risks

and control losses are increasing. Organizations, governments and UN bodies are working more closely to share information on the impact of disaster risk. Examples include R!SE, a joint UN-PwC initiative, which looks at how to embed disaster risk management into corporate strategy and investment decisions.

Governments also are starting to develop plans and policies for addressing climatic instability, though for the most part policy actions remain unpredictable, inconsistent and reactive.

Developments in risk modeling

A new generation of catastrophe models is ushering in a transformational expansion in both geographical

breadth and underwriting applications. Until recently, cat models primarily concentrated on developed market peak zones (such as Florida windstorm). As the unexpectedly high insurance losses from the 2010 Chilean earthquake and the 2011 Thai floods highlight, this narrow focus has failed to take account of the surge in production and asset values in fast-growth SAAAME markets (South America, Africa, Asia and the Middle East). The new models cover many of these previously non-modeled zones.

The other big difference for insurers is their newfound ability to plug different analytics into a single platform. This offers the advantages of being able to understand where there may be pockets of untapped capacity or, conversely, hazardous concentrations. The result is much more closely targeted risk selection and pricing.

The challenge is how to build these models into the running of the business. Cat modeling has traditionally been the preserve of a small, specialized team. The new capabilities are supposed to be easier to use and hence open to a much wider array of business, IT and analytical teams. It’s important to determine the kind of talent needed

to make best use of these systems, as well as how they will change the way underwriting decisions are made.

Emerging developments include new monitoring and detection systems, which draw

on multiple fixed and drone sensors.

Challenges for evaluating and pricing risk

Beyond catastrophe risks are disruptions to asset/insured values resulting from constraints on water, land and other previously under-evaluated risk factors. There are already examples of industrial plants that have had to close because of limited access to water.

Economic: Adapting to a Multipolar World

Struggling to sustain margins

The challenging economic climate has

held back discretionary spending on life, annuities and pensions, with the impact being compounded by low interest rates and the resulting difficulties in sustaining competitive returns for policyholders. The keys to sustaining margins are likely to be simple, low-cost, digitally distributed products for the mass market and use of the latest risk analytics to help offer guarantees at competitive prices.

The challenges facing P&C insurers center on low investment returns and a softening market. Opportunities to seek out new customers and boost revenues include strategic alliances. Examples could include affinity groups, manufacturers or major retailers. A further possibility is that one of the telecoms or Internet giants will want a tie-up with an insurer to help it move into the market.

More than 30% of insurance CEOs

now see alliances as an opportunity to strengthen innovation. Examples include the partnership between a leading global reinsurer and software group, which aims to provide more advanced cyber risk protection for corporations.

Surprisingly, only 10% of insurance CEOs are looking to partner with start- ups, even though such alliances could provide valuable access to the new ideas and technologies they need.

SAAAME growth

Growth in SAAAME insurance markets will continue to vary. Slowing growth

in some major markets, notably Brazil, could hold back expansion. In others, notably India, we are actually seeing a decline in life, annuity and pension take-up as a result of the curbs on commissions for unit-linked insurance plans (ULIP). Further development in capital markets will be necessary to encourage savers to switch their deposits to insurance products.

As the reliance on agency channels adds to costs, there are valuable opportunities to offer cost- effective digital distribution. Successful models of inclusion include an Indian national health insurance program, which is aimed at poorer households and operates through a public/private partnership. More than 30 million households have taken up the smart cards that provide them with access to hospital treatment.

The already strong growth (10% a year) in micro-insurance is also set to increase, drawing on models developed within micro-credit. The challenge for insurers is the need to make products that are sufficiently affordable and comprehensible to consumers who have little or no familiarity with the concept of insurance.

Rather than waiting for a market-wide alignment of data and pricing, some insurers have moved people onto the ground to build up the necessary data sets, often working in partnership with governments, regional and local development authorities and banks and local business groups.

Urbanization

The urban/rural divide may actually be more relevant to growth opportunities ahead than the emerging/developed market divide. In 1800, barely one in 50 people lived in cities. By 2009, urban dwellers had become a majority of the global population for the first time. Now, every week, 1.5 million people are added to the urban population, the bulk of them in SAAAME markets.

Cities are the main engines of the global economy, with 50% of global GDP generated in the world’s 300 largest metropolitan areas. The result is more wealth to protect. Infrastructure development alone will generate an estimated $68 billion in premium income between now and 2030. Urban citizens will be more likely to be exposed to insurance products and have access to them. Urbanization is also likely to increase purchases of life, annuities and pensions’ products, as people migrating into cities have to make individual provision for the future rather than relying on extended family support.

Yet as the size and number of mega-metropolises grow, so does the concentration of risk. Key areas of exposure go beyond property and catastrophe coverage to include the impact of air pollution and poor water quality and sanitation on health.

Tackling under-insurance

A Lloyd’s report comparing the level

of insurance penetration and natural catastrophe losses in countries around the world found that 17 fast-growth markets had an annualized insurance deficit of $168 billion, creating threats to sustained economic growth and the ability to recover from disasters.

Political: Harmonization, Standardization and Globalization of the Insurance Market

Government in the tent

At a time when all financial services businesses face considerable scrutiny, strengthening the social mandate through closer alignment with government goals could give insurers greater freedom. Insurers also could be in a stronger position to attract quality talent at a time when many of the brightest candidates are looking for more meaning from their chosen careers.

Government and insurers can join forces in the development of effective retirement and healthcare solutions (although there are risks). Further opportunities include a risk partnership approach to managing exposures that neither insurers nor governments have either the depth of data or financial resources to cover on their own, notably cyber, terrorism and catastrophe risks.

Impact of regulation

Insurers have never had to deal with an all-encompassing set of global prudential regulations comparable to the Basel Accords governing banks. But this is what the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and its sponsors in the G20 now want to see as the baseline requirements for not just the global insurers designated as systemically risky, but also a tier of internationally active insurance groups.

The G20’s focus on insurance regulation highlights the heightened politicization of financial services. Governments want to make sure that taxpayers no longer have to bail out failing financial institutions. The result

is an overhaul of capital requirements

in many parts of the world and a new basic capital requirement for G-SIIs. The other game-changing development is the emergence of a new breed of cross-state/cross-border regulator, which has been set up to strengthen co-ordination of supervision, crisis management and other key topics. These include the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) and the Federal Insurance Office (FIO) in the U.S.

Dealing with these developments requires a mechanism capable of looking beyond basic operational compliance at how new regulation will affect the strategy and structure of the organization and using this assessment to develop a clear and coherent company-wide response.

Technology will allow risk to be analyzed in real time, and predictive models would enable supervisors to identify and home in on areas in need

of intervention. Regulators would also be able to tap into the surge in data and analysis within supervised organizations, creating the foundations for machine-to-machine regulation.

A more unstable world

From the crisis in Ukraine to the rise of ISIS, instability is a fact of life. Pressure on land and water, as well as oil and minerals, is intensifying competition for strategic resources and potentially bringing states into conflict. The ways these disputes are playing out is also impinging on corporations to an ever-greater extent, be this trade sanctions or state-directed cyber-attacks.

Businesses, governments and individuals also need to understand the potential causes of conflict and their ramifications and develop appropriate contingency planning and response. At the very least, insurers should seek to model these threats and bring them into their overall risk evaluations. For some, this will be an important element of their growing role as risk advisers and mitigators. Investment firms are beginning to hire ex-intelligence and military figures as advisers or calling in dedicated political consultancies as part of their strategic planning. More insurers are likely to follow suit.

The final article in this series will look at scenarios that could play out for insurers and will lay out a way to formulate an effective strategy. If you want a copy of the report from which these articles are excerpted, click here.