Who do property and casualty insurance customers turn to when they need help?

In the past, answers have included insurance agents, customer helplines and company websites. Today, however, customers are increasingly likely to consult Alexa, Siri or Cortana.

As voice assistants gain popularity in homes, in cars and on smartphones, they’re also gaining traction as a marketing tool. Here, we look at the ways in which insurance companies are using voice assistants as part of their marketing and sales strategy, as well as what to expect in the near future.

How Voice Assistants Are Changing Marketing

Voice assistants commonly come in one of two forms: wireless speakers that can be placed in the home or office, or as built-in tools on smartphones. iPhones and various Android devices have had them for a few years now.

In some ways, voice assistants work similarly to visual or text-based tools like smartphone apps and Google search bars. The user asks a question or enters a command, and the device responds to it. Voice assistants like Alexa even offer apps, or “skills,” that work similarly to smartphone apps — except they rely on audio rather than visuals to share information, TechCrunch’s

Sarah Perez writes.

The audio-based approach changes the ways in which both search results and apps work on voice assistant devices. A text-based Google search, for instance, returns a list of links from which the user can choose. A voice-based search, however, tends to return the single response the AI thinks best fits the user’s query.

Some experts praise this option for its speed and flexibility. “Since voice flattens menus, it will make daily tasks far easier to complete,” Jelli CEO

Mike Dougherty says. Yet it also puts additional pressure on marketing teams to ensure that their content gets chosen by the various search engines that inform each voice-based device, says

Richard Yao, senior associate of strategy and content at IPG Media Lab.

Voice assistants haven’t just changed how search results are presented. They have also changed how users launch searches in the first place, says More Visibility’s

Jill Goldstein. While text-based searches tend to focus on two or three keywords, voice-based searches use full, natural-language sentences. These often start with question words like “what,” “how” or “when.”

See also: Insurtech Starts With ‘I’ but Needs ‘We’

These questions give marketers insight into where shoppers are in their buying journey and how best to meet their needs — but only if marketing teams are collecting and using this information, says

Tyler Riddell, vice president of marketing for eSUB Construction Software.

Not only are marketing teams learning to adapt to the differences between audio and visual, but they’re also learning how to adapt to a search tool that adapts itself.

Because voice assistants use artificial intelligence and machine learning, they can adapt to changes in search terms, says Gartner analyst

Ranjit Atwal. The onboard AI is designed to learn over time, gaining a better sense of how users frame their queries and the sort of information they may be looking for.

‘Alexa, Find Me Auto Insurance’: The Rising Demand for Voice Search

Based on recent sales trends, 55% of U.S. households are expected to have a smart home speaker, with voice assistance enabled, in their houses by the end of 2019,

Dara Treseder at Adweek reports. Voice assistants are also a mainstay of many smartphones, from Apple’s Siri to Google’s voice search option triggered by saying, “OK, Google.”

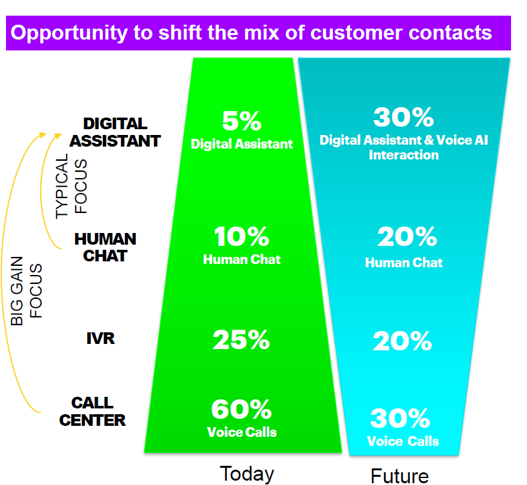

Insurance customers increasingly prefer to include digital channels in their search for property and casualty insurance. With voice assistants occupying millions of smartphones and a wide range of other devices, customers increasingly prefer to rely on these tools, as well.

Nearly half (46%) of insurance customers already use voice search tools at least once per day, according to

Shane Closser at Property Casualty 360. One in four want their voice assistants to be able to give them more information on insurance agents and products. One in three wanted to use voice assistants to book appointments with a particular insurance agent.

Service-based companies that offer “highly complex and highly personal” services are uniquely suited to thrive in the voice search era, says Adweek’s

Julia Stead. While Stead focuses on travel, finance and healthcare, her analysis applies to P&C insurers, as well, because these companies also offer services that have long been accessed via voice (phone), are tailored to the needs of each customer and often require access at odd locations or hours.

And while the conversation about tech innovation often focuses on younger users, voice assistants are increasingly popular with older insurance customers.

See also: Future of Insurance Looks Very Different

Lauryn Chamberlain at GeoMarketing.com says that 37% of consumers age 50 and older say they use a voice assistant, often because simply speaking to a smart speaker or phone is easier than tapping, swiping or reducing a question to its key search terms. In other words, older users can think of their voice assistants as a helpful background entity rather than as a device.

In short, voice assistants are cutting across demographics. They’re entering more homes and workspaces. And insurance customers want to use them to secure coverage.

How P&C Insurers Are Incorporating Voice Into Their Marketing

Several insurance companies are already experimenting with voice assistant tools as part of their own marketing process, according to

Danni Santana at Digital Insurance. For instance, Nationwide, Liberty Mutual (and subsidiary SafeCo) and Farmers have all launched Amazon Echo Skills.

Progressive, meanwhile, joined Google Home in March 2017, the first insurance carrier to do so, according to

Rachel Brown at Mobile Marketer.

Other insurance companies have experimented with different approaches.

Amica Mutual Insurance, for example, launched an Alexa skill that doesn’t connect users to their individual accounts. Rather, it offers information in more than a dozen categories to help users better understand billing, discounts, storm preparation and more.

With the development of Alexa skills and similar tools, brands are thinking about how a voice assistant’s sound affects their brand development, says

Jennifer Harvey, VP of branding and communications at Bynder. The choice of voice tone, pitch and speed can all send a powerful message about an insurer’s brand and culture, whether it’s reassuring, serious, cheerful or anything in between.

One of the big opportunities for insurance companies and voice assistants is access. Currently, voice assistants can take on many simple tasks but can’t always handle a transaction as complex as ensuring a customer receives the right home or auto coverage for their needs. Yet developments in AI and voice recognition indicate this may change. “Alexa is already capable of placing a complicated pizza order,” says

Inbal Lavi, CEO of Webpals Group, “underscoring that voice assistants will act as more than middlemen.”

For now, however, even the digital middleman approach can benefit potential and current P&C insurance customers and the companies that serve them. “We want to enable easy access for our customers,” says

Alexander Bernert, head of brand management at Zurich Insurance. “Consumers do not necessarily think of taking out disability insurance between 9 am and 5 pm, but maybe even shortly before midnight.”

It can be tough to reach an insurance agent shortly before midnight. But a voice assistant can find one, provide information and even schedule an appointment — making it easier for potential customers to turn into actual purchasers.

In a world where insurance customers already do research and contact insurers

via multiple channels, voice assistants are a natural frontier for insurance marketing.