The Graveyard of Digital Health

The healthcare industry is overripe for disruption from the tech world, yet the process of working with healthcare providers is not easy.

The healthcare industry is overripe for disruption from the tech world, yet the process of working with healthcare providers is not easy.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

I'll be brief, because I'm running around at InsureTech Connect in Las Vegas (as are, I imagine, many of you. Come by and see us in Room 305 of the MGM Grand Conference Center, if you are.) But I do want to tee up an idea we've been discussing: What if we tried combining workers' comp with health insurance?

Yes, they've historically been very different. Workers' comp sprang from the grand bargain of a century-plus ago, designed to free both workers and employers from potentially debilitating claims of negligence. Health insurance grew out of charity when care was limited and cheap—even when Blue Cross began selling insurance, in 1929, it cost just $6 a year—and took a left turn during World War II when a government tax break established employer-issued health insurance as the standard in the U.S.

But history isn't destiny. In fact, an idea like combining workers' comp and health insurance could allow for some creativity, in the midst of uncertainty, that isn't possible within today's silos.

The combination would do away with a lot of today's inefficiencies. While workers' comp was set up to be no-fault, it's more like fault-fault-fault today. Everybody reviews everything. Lawyers often get involved early. So do doctors—and not just those treating the injured directly; you have doctors reviewing the doctors, and maybe doctors reviewing the doctors who review the doctors. What if the goal just became keeping the employee healthy, whether the problem was a workplace injury or strep throat?

A lot of complexity would fall away. Perhaps even more than we know. The psychosocial approach to workers' comp finds that workers react well when they feel they're on the same side as the employer—trying to get healthy and back to productive work—and react poorly when they feel like the employer is being legalistic, uncaring, etc. If the whole goal was just a healthy employee, imagine what might happen.

A fair amount of administrative effort and expense goes into deciding whether workers' comp or heath insurance covers a problem, but what if the two lines of coverages were combined...?

My innovation mantra has long been, Think Big, Start Small, Learn Fast, so how would we start small after having this big idea? I can imagine Texas and Oklahoma being hospitable, as long as they've been experimenting with ways to opt out of traditional workers' comp. Perhaps a small county in California would allow a melding of workers' comp and healthcare, so we could gather some data. In any case, let's find a way to try the idea.

I can already see a major issue: deductibles. Workers' comp doesn't have them, while health insurance may have massive ones. So, there has to be some way to cover workplace injuries immediately while not providing carte blanche for employees to have whatever healthcare treatment they want.

But that issue feels like a detail, especially if we experiment before rolling out a new plan broadly. There has to be some way to assign responsibility for routine issues to individuals, while protecting injured workers.

Please let me know what you think. And, as I said, maybe we can even do this in person, if you're at ITC this week.

Cheers,

Paul Carroll

Editor-in-Chief

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Paul Carroll is the editor-in-chief of Insurance Thought Leadership.

He is also co-author of A Brief History of a Perfect Future: Inventing the Future We Can Proudly Leave Our Kids by 2050 and Billion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn From the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last 25 Years and the author of a best-seller on IBM, published in 1993.

Carroll spent 17 years at the Wall Street Journal as an editor and reporter; he was nominated twice for the Pulitzer Prize. He later was a finalist for a National Magazine Award.

Many do not even try to sell this important commercial coverage. This combination of importance and silence equals a wicked E&O exposure.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Chris Burand is president and owner of Burand & Associates, a management consulting firm specializing in the property-casualty insurance industry.

Most service planning in catastrophes is highly manual, involving multiple spreadsheets and guesswork; AI-driven capacity planning is seamless.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Given the exclusions in CGL and product liability policies, vaping businesses cannot simply assume that they have the necessary coverage.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

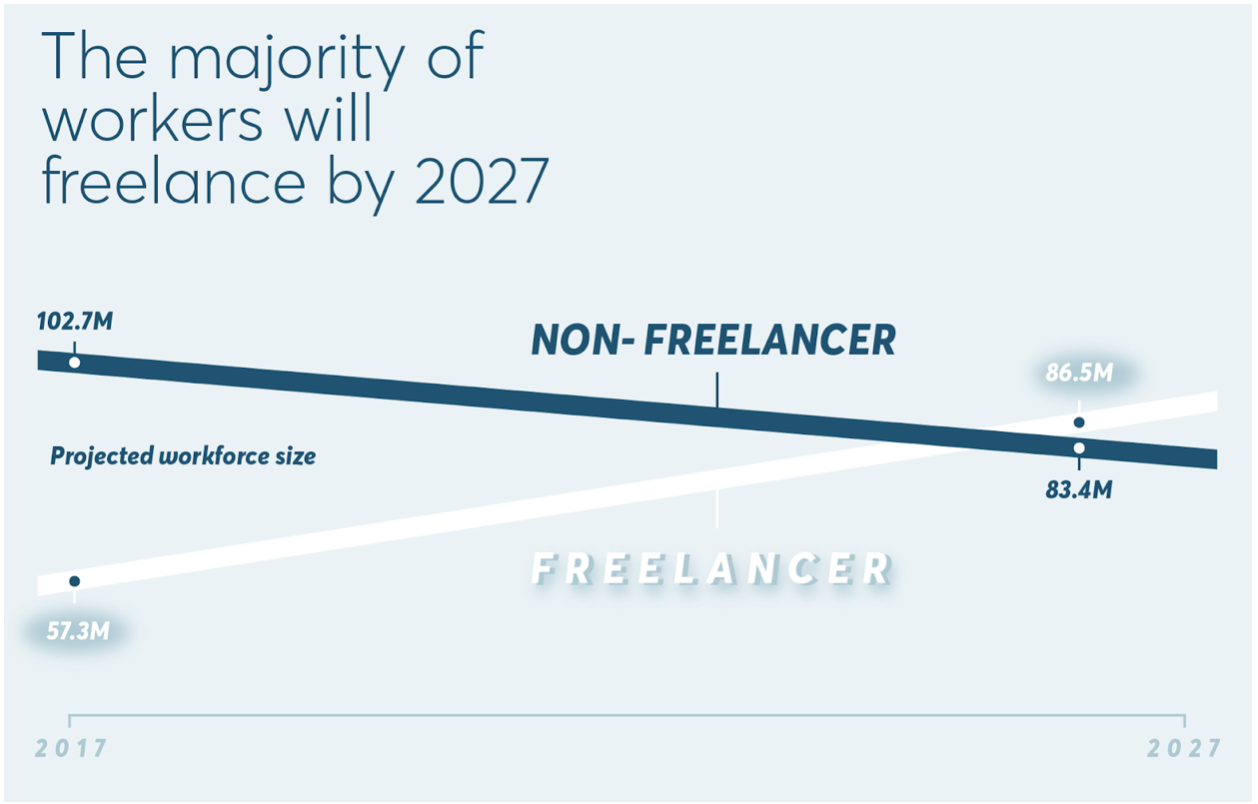

The most successful brokers will be those who figure out how to serve the massive and growing population of self-employed workers.

The future of work is coming. Where is the future of insurance? Source: Freelancers Union.[/caption]

Why does health insurance for the self-employed matter?

I am a licensed broker and a former freelancer, so this issue is personal for me. I spent most of 2018 working as a self-employed growth consultant. I did paid projects from a desk at a coworking space and got to know the other people there — gifted technical, creative and business professionals with the courage and skills to bet on themselves. And I learned what every self-employed person already knows: This work can be exhilarating, but it’s not easy, and the lack of affordable health insurance hurts not only individual workers but their families, and their long-term health.

See also: Empathy Transforms Health Insurance

Self-employed people including 1099 contractors can’t get coverage in most group policies. They can buy comprehensive individual plans during open enrollment, but it gets more expensive every year, and those earning more than $50,000 per year don’t get subsidies to offset the price. Outside of open enrollment, there are no comprehensive healthcare options for the self-employed–which is a massive problem.

How does this affect you? If you sell group plans to organizations with a large base of independent 1099 contractors, you already know the answer--you’ve got a large and growing population, and nothing great to sell them. The most innovative and successful brokers in the next 10 years will be those who can figure out how to serve this massive and growing population of self-employed workers.

The future of work deserves the future of health insurance. How can healthcare plans evolve?

Brokers and self-employed people both need better options. Luckily, we’re starting to see some new options come online that are getting traction.

Self-employed people can buy short-term plans, but these plans typically cap payouts and don’t cover preexisting conditions or many essential health benefits. They can join health-sharing ministries, typically composed of religious people who aspire but do not commit to sharing in each other's healthcare costs, but their care may not get covered, and monthly payments are not tax-deductible.

Decent, which I founded, recently launched in Austin, Texas, in partnership with the Texas Freelance Association, offering the most affordable comprehensive plans on the market for self-employed people and their families. All plans include unlimited free primary care with a personal doctor. Decent sells year 'round, including to people without a qualifying life event, and will be expanding throughout Texas and beyond soon.

So what is the future of health insurance?

Whatever products eventually win in the market, getting employers out of the health insurance equation will make the healthcare market work more like other markets, where suppliers compete to serve customers on quality, price, and convenience.

See also: 5 Health Insurance Tips for Small Business

America’s self-employed workforce is relatively healthy, wealthy and politically active. A revitalized individual market will encourage regulators to make subsidies available for insurance purchased in the private market, not just on government exchanges.

At the end of the day, capitalism is about choice. People want more and better options. As a growing number of Americans choose the insurance they want rather than taking the insurance their employer gives them, suppliers and brokers will provide what the market needs. At Decent, we anticipate that the future of health insurance is refreshingly similar to the future of other markets that have evolved to serve the consumer: more choices, more customization and better deals for the diverse population that makes up our country, including the rising tide of the American self-employed.

The future of work is coming. Where is the future of insurance? Source: Freelancers Union.[/caption]

Why does health insurance for the self-employed matter?

I am a licensed broker and a former freelancer, so this issue is personal for me. I spent most of 2018 working as a self-employed growth consultant. I did paid projects from a desk at a coworking space and got to know the other people there — gifted technical, creative and business professionals with the courage and skills to bet on themselves. And I learned what every self-employed person already knows: This work can be exhilarating, but it’s not easy, and the lack of affordable health insurance hurts not only individual workers but their families, and their long-term health.

See also: Empathy Transforms Health Insurance

Self-employed people including 1099 contractors can’t get coverage in most group policies. They can buy comprehensive individual plans during open enrollment, but it gets more expensive every year, and those earning more than $50,000 per year don’t get subsidies to offset the price. Outside of open enrollment, there are no comprehensive healthcare options for the self-employed–which is a massive problem.

How does this affect you? If you sell group plans to organizations with a large base of independent 1099 contractors, you already know the answer--you’ve got a large and growing population, and nothing great to sell them. The most innovative and successful brokers in the next 10 years will be those who can figure out how to serve this massive and growing population of self-employed workers.

The future of work deserves the future of health insurance. How can healthcare plans evolve?

Brokers and self-employed people both need better options. Luckily, we’re starting to see some new options come online that are getting traction.

Self-employed people can buy short-term plans, but these plans typically cap payouts and don’t cover preexisting conditions or many essential health benefits. They can join health-sharing ministries, typically composed of religious people who aspire but do not commit to sharing in each other's healthcare costs, but their care may not get covered, and monthly payments are not tax-deductible.

Decent, which I founded, recently launched in Austin, Texas, in partnership with the Texas Freelance Association, offering the most affordable comprehensive plans on the market for self-employed people and their families. All plans include unlimited free primary care with a personal doctor. Decent sells year 'round, including to people without a qualifying life event, and will be expanding throughout Texas and beyond soon.

So what is the future of health insurance?

Whatever products eventually win in the market, getting employers out of the health insurance equation will make the healthcare market work more like other markets, where suppliers compete to serve customers on quality, price, and convenience.

See also: 5 Health Insurance Tips for Small Business

America’s self-employed workforce is relatively healthy, wealthy and politically active. A revitalized individual market will encourage regulators to make subsidies available for insurance purchased in the private market, not just on government exchanges.

At the end of the day, capitalism is about choice. People want more and better options. As a growing number of Americans choose the insurance they want rather than taking the insurance their employer gives them, suppliers and brokers will provide what the market needs. At Decent, we anticipate that the future of health insurance is refreshingly similar to the future of other markets that have evolved to serve the consumer: more choices, more customization and better deals for the diverse population that makes up our country, including the rising tide of the American self-employed.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

The story of, and lessons from, the first fully digital life insurance company (founded way back in 2006).

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Roger Peverelli is an author, speaker and consultant in digital customer engagement strategies and innovation, and how to work with fintechs and insurtechs for that purpose. He is a partner at consultancy firm VODW.

Reggy de Feniks is an expert on digital customer engagement strategies and renowned consultant, speaker and author. Feniks co-wrote the worldwide bestseller “Reinventing Financial Services: What Consumers Expect From Future Banks and Insurers.”

Do you take the time to grow each team member, making the person better-prepared for tomorrow?

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Mike Manes was branded by Jack Burke as a “Cajun Philosopher.” He self-defines as a storyteller – “a guy with some brain tissue and much more scar tissue.” His organizational and life mantra is Carpe Mañana.

80,000-pound tractor trailer rigs, which number over 2 million in the U.S., will disrupt the trucking industry as fleets convert to autonomous units.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

As a renown workers’ compensation expert and industry thought leader for 40 years, Jeff Pettegrew seeks to promote and improve understanding of the advantages of the unique Texas alternative injury benefit plan through active engagement with industry and news media as well as social media.

At first blush, there wouldn't seem to be much in common between the unionized workers at GM who just walked out on strike and the gig workers at companies like Uber and Lyft that would have to be classified as employees, not contractors, and provided benefits under legislation that California approved last week. Yes, GM workers make cars, and Uber/Lyft drivers use cars, but how else are those stamping out auto bodies on an assembly line eight hours a day related to those who opt in and out of providing rides in their cars?

The answer is health insurance. The workers' issues take different routes to get to health insurance, but they both land there, with a thud.

Among Uber/Lyft drivers and other gig workers, many are just looking for any kind of health coverage—which accounts for the vast majority of the benefits that employers very much don't want to provide these workers. GM workers want wage gains that GM could easily afford if so much of compensation didn't get sucked up by health insurance. GM spends $9 an hour per worker on health insurance, a cost that logic suggests could be cut in half, given that the U.S. spends twice as much as other developed countries on healthcare while getting slightly below-average care. Turn those cost savings into wages, and workers could receive an extra $9,360 a year. That would be a raise of 14% to 26% for line workers, right off the top. Think the UAW would be happy with that?

The new California law, the GM strike and scads of other evidence suggest that our current healthcare system, including today's approach to health insurance, can't continue indefinitely, and, as Stein's Law says, "If something cannot go on forever, it will stop."

I have a broad prescription, if you will. (It has nothing to do with a political stance.) I even have a suggestion on how to get there from here. But, first, it's worth understanding how we stumbled into today's predicament, through more than a century of haphazard actions that are now defended zealously by lobbyists but that don't come close to resembling a plan.

Health insurance began as a charitable endeavor in the early 1900s, mostly so that workers who got injured or fell ill would have their wages covered while they sought care. Treatment didn’t cost much because there wasn’t much care to be offered. Treatment didn’t last long, either – generally, within a couple of weeks, the patient either recovered and returned to work or died. (Harsh, but true.) When Blue Cross was founded at Baylor University in 1929, it charged enrollees just $6 a year.

Then World War II came along. The federal government instituted a wage freeze—after all, companies were pitching in to win the war. Unions, much stronger in those days, pushed companies to improve benefits in lieu of wage increases, and businesses went along. Remember, at the time healthcare was cheap. The federal government endorsed the arrangement by giving businesses a tax break on the cost of health insurance they provided.

And that was that. The unique structure of today's health insurance market in the U.S. was put in place.

In the decades since, having employers as suppliers of health insurance has divided the country into haves and have-nots in a way that no one anticipated. You typically got robust insurance through your employer; you received a lesser form through the government; or you likely did without. Only 7% of Americans had individual policies in 2017, while 49% were insured through employers; 9% were not insured, and Medicare or Medicaid covered the remaining 35%.

The divide got worse in the 1980s and 1990s when insurers switched from non-profit to for-profit status. The five-headed behemoth known as BUCAH (for the Blues, United Healthcare, Cigna, Aetna and Humana) marketed based on the discounts they offered employers. That, perversely, encouraged providers to raise prices—that way, the insurers' discounts looked all the better.

By now, as a doctor said recently, "It'd be like…your car mechanic…saying, 'Well, I think it’s going to be $17,000 to get this fixed,' and you say, 'Well, how about $149?'"

That's mostly fine if you get your health insurance from an employer, which gets the discount, but those who don't get insurance at work are left out. They're expected to pay that $17,000 list price. In fact, providers go to great lengths to make sure they do.

Today, healthcare and health insurance prices are finally rising so much that even the haves are struggling. Employers have been pushing more of the insurance cost onto employees, many of whom can't afford it and opt for deductibles so high that they're afraid to use their insurance.

What do we do now?

My answer: Insurance needs to switch from being associated with the employer to being associated with the individual. That change has already happened with retirement funds, as corporate America has gone from providing pensions a generation ago to perhaps contributing to IRA and 401(k) savings today. So, we know such a change is possible.

It could get started rather easily, simply by acknowledging that the tax break given to employees three-quarters of a century ago was a well-meaning stopgap in extraordinary circumstances that shouldn't define our healthcare system for eternity. Then we eliminate the tax break.

Now, that change would be fought as hard as can be because undoing that credit would be the start of a series of upheavals to a nearly $4 trillion-a-year healthcare system—and people will do a lot to protect $4 trillion. Wars have been fought for less.

But it's possible to outmaneuver the naysayers and define a rational solution through an exercise called a future history, which I've also seen referred to as a clean sheet of paper. Basically, you pick a time in the future and imagine in detail the best possible version of something, such as the healthcare system. Then you write an article dated in the future that explains how you, hypothetically, got there.

If you pick the right time frame—usually three to five years for a company but probably 20 or 30 years in the case of something as complex as healthcare in the U.S.—you can eliminate a lot of the angst. You aren't talking about reducing anybody's bonus this year. If you think about healthcare in 2050, you aren't even talking to those who will be the big players then; they'll be long retired. And everybody will have plenty of time to prepare.

Nobody can defend something like today's system, based on a historical anomaly that has led to wildly, erratically high prices and such a divide between haves and have-nots, so let's design something better. Let's design something. Let's design something.

I prefer ideas like those proposed by economist Uwe Reinhardt, but almost anything would be better than what we have, because we won't fall into it. The change won't happen in time to help GM and its unions or Uber and Lyft and their gig economy workers, but at least we'll be heading in a rational direction.

Cheers,

Paul Carroll

Editor-in-Chief

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Paul Carroll is the editor-in-chief of Insurance Thought Leadership.

He is also co-author of A Brief History of a Perfect Future: Inventing the Future We Can Proudly Leave Our Kids by 2050 and Billion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn From the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last 25 Years and the author of a best-seller on IBM, published in 1993.

Carroll spent 17 years at the Wall Street Journal as an editor and reporter; he was nominated twice for the Pulitzer Prize. He later was a finalist for a National Magazine Award.