Many life insurance executives with whom we have spoken say that their business needs to fundamentally change to be relevant in today’s market. Life insurance does face formidable challenges.

First, let’s take a hard look at some statistics. In 1950, there were approximately 23 million life policies in the U.S., covering a population of 156 million. In 2010, there were approximately 29 million policies covering a population of 311 million. The percentage of families owning life insurance assets has decreased from more than a third in 1992 to less than a quarter in 2007. By contrast, while less than a third of the population owned mutual funds in 1990, more than two-fifths (or 51 million households and 88 million investors) did by 2009.

A number of socio-demographic, behavioral economic, competitive and technological changes explain the trends -- and the need for reinventing life insurance:

- Changing demography: Around 12% of men and an equal number of women were between the ages of 25 and 40 in 1950. However, only 10% of males and 9.9% of females were in that age cohort in 2010, and the percentage is set to drop to 9.6% and 9.1%, respectively, by 2050. This hurts life insurance in two main ways. First, the segment of the overall population that is in the typical age bracket for purchasing life insurance decreases. Second, as people see their parents and grandparents live longer, they tend to de-value the death benefits associated with life insurance.

- Increasingly complex products: The life insurance industry initially offered simple products with easily understood death benefits. Over the past 30 years, the advent of universal and variable universal life, the proliferation of various riders to existing products and new types of annuities that highlight living benefits significantly increased product diversity but often have been difficult for customers to understand. Moreover, in the wake of the financial crisis, some complex products had both surprising and unwelcome effects on insurers themselves.

- Individual decision-making takes the place of institutional decision-making: From the 1930s to the 1980s, the government and employers were providing many people life insurance, disability coverage and pensions. However, since then, individuals increasingly have had to make protection/investment decisions on their own. Unfortunately for insurers, many people have eschewed life insurance and spent their money elsewhere. If they have elected to invest, they often have chosen mutual funds, which often featured high returns from the mid-1980s to early 2000s.

- Growth of intermediated distribution: The above factors and the need to explain complex new products led to the growth of intermediated distribution. Many insurers now distribute their products through independent brokers, captive agents, broker-dealers, bank channels and aggregators and also directly. It is expensive and difficult to effectively recruit, train and retain such a diffuse workforce, which has led to problems catering to existing customers.

- Increasingly unfavorable distribution economics: Insurance agents are paid front-loaded commissions, some of which can be as high as the entire first-year premiums, with a small recurring percentage of the premium thereafter. Moreover, each layer adds a percentage commission to the premiums. All of this increases costs for both insurers and consumers. In contrast, mutual fund management fees are only 0.25% for passive funds and 1% to 2% for actively managed funds. In addition, while it is difficult to compare insurance agency fees, it is relatively easy to do so with mutual fund management fees.

- New and changing customer preferences and expectations: Unlike their more patient forebears, Gens X and Y – who have increasing economic clout – demand simple products, transparent pricing and relationships, quick delivery and the convenience of dealing with insurers when and where they want. Insurers have been slower than other financial service providers in recognizing and reacting to this need.

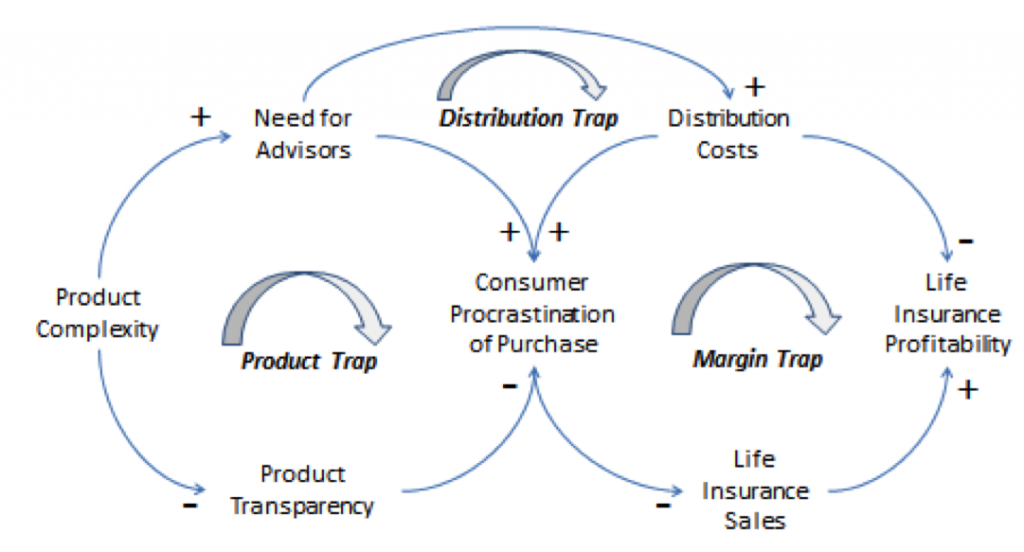

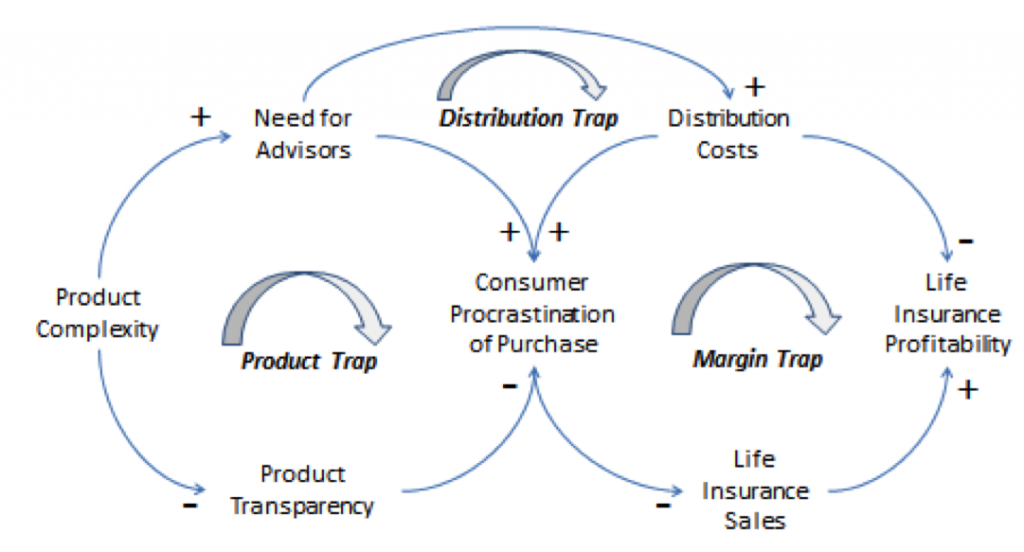

A vicious cycle has begun (see graphic below). Insurers claim that, in large part because of product complexity, life insurance is “sold and not bought,” which justifies expensive, intermediated distribution. For many customers, product complexity, the need to deal with an agent, the lack of perceived need for death benefits and cost-of-living benefits make life products unappealing. In contrast, the mutual fund industry has grown tremendously by exploiting a more virtuous cycle: It offers many fairly simple products that often are available for direct purchase at a nominal fee.

Reasons for optimism

Reasons for optimism

Despite the bleak picture we have painted so far, we believe that reinventing life insurance and redesigning its business model are possible. This will require fundamental rethinking of value propositions, product design, distribution and delivery mechanisms and economics. Some of the most prescient insurers are already doing this and focusing on the following to become more attractive to consumers:

- From living benefits to well-being benefits: There is no incentive built into life policy calculations for better living habits because there traditionally has been very little data for determining the correlation between these behaviors and life expectancy. However, the advent of wearable devices, real-time monitoring of exercise and activity levels and advances in medical sciences have resulted in a large body of behavioral data and some preliminary results. There are now websites that can help people determine their medical age based on their physical, psychological and physiological behaviors and conditions. We refer to all these factors collectively as “well-being behaviors.” Using the notion of a medical age or similar test as part of the life underwriting process, insurers can create an explicit link between “well-being behaviors” and expected mortality. This link can fundamentally alter the relevance and utility of life insurance by helping policyholders live longer and more healthily and by helping insurers understand and price risk better.

- From death benefits to quality of life: Well-being benefits promise to create a more meaningful connection between insurers and policyholders. Rather than just offering benefits when a policyholder dies, insurers can play a more active role in changing policyholder behaviors to delay or help prevent the onset of certain health conditions, promote a better quality of life and even extend insureds’ life spans. This would give insurers the opportunity to engage with policyholders on a daily (or even more frequent) basis to collect behavioral data on their behalf and educate them on more healthy behaviors and lifestyle changes. To encourage sharing of such personal information, insurers could provide policyholders financial (e.g., lower premiums) and non-financial (e.g., health) benefits.

- From limited to broad appeal: Life insurance purchases are increasingly limited to the risk-averse, young couples and families with children. Well-being benefits are likely to appeal to additional, typically affluent segments that tend to focus on staying fit and healthy, including both younger and active older customers. For a sector that has had significant challenges attracting young, single, healthy individuals, this represents a great opportunity to expand the life market, as well as attract older customers who may think it is too late to purchase life products.

- From long-term to short-term renewable contracts: Typical life insurance contracts are for the long term. However, this is a deterrent to most customers today. Moreover, behavioral economics shows us that individuals are not particularly good at making long-term saving decisions, especially when there may be a high cost (i.e., surrender charges) to recover from a mistake. Therefore, individuals tend to delay purchasing or rationalize not having life insurance at all. With well-being benefits, contract durations can be much shorter -- even only one year.

- Toward a disintermediated direct model: Prevailing industry sentiment is that “life insurance is sold, not bought,” and by advisers who can educate and advise customers on complex products. However, well-being benefits offer a value proposition that customers can easily understand (e.g., consuming X calories per day and exercising Y hours a day can lead to a decrease in medical age by Z months), as well as much shorter contract durations. Because of their transparency, these products can be sold to the consumer without intermediaries. More health-conscious segments (e.g., the young, professional and wealthy) also are likely to be more technologically savvy and hence prefer direct online/call center distribution. Over time, this model could bring down distribution costs because there will be fewer commissions for intermediaries and fixed costs that can be amortized over a large group of early adopters.

We realize that life insurers tend to be very conservative and skeptical about wholesale re-engineering. They often demand proof that new value propositions can be successful over the long term. However, there are markets in which life insurers have successfully deployed the well-being value proposition and have consistently demonstrated superior performance over the past decade. Moreover, there are clear similarities to what has happened in the U.S. auto insurance market over the last 20 years. Auto insurance has progressively moved from a face-to-face, agency-driven sale to a real-time, telematics-supported, transparent and direct or multi-channel distribution model. As a result, price transparency has increased, products are more standardized, customer switching has increased and real-time information is increasingly informing product pricing and servicing.

Implications

Significantly changing products and redesigning a long-established business model is no easy task. The company will have to redefine its value proposition, target individuals through different messages and channels, simplify product design, re-engineer distribution and product economics, change the underwriting process to take into account real-time sensor information and make the intake and policy administration process more straight-through and real-time.

So, where should life insurers start? We propose a four step “LITE” (Learn-Insight-Test-Enhance) approach:

- Learn your target segments’ needs. Life insurers should partner with health insurers, wellness companies and manufacturers of wearable sensors to collect data and understand the exercise and dietary behaviors of different customer segments. Some leading health and life insurers have started doing this with group plans, where employers have an incentive to encourage healthy lifestyles among their employees and therefore reduce claims and premiums.

- Build the models that can provide insight. Building simulation models of exercise and dietary behavior and their impact on medical age is critical. Collecting data from sensors to calibrate these models and ascertain the efficacy of these models will help insurers determine appropriate underwriting factors.

- Test initial hypotheses with behavioral pilots. Building and calibrating simulation models will provide insights into the behavioral interventions that need field testing. Running pilots with target individuals or specific employer groups in a group plan will help test concepts and refine the value proposition.

- Enhance and roll out the new value proposition. Based on the results of pilot programs, insurers can refine and enhance the value proposition for specific segments. Then, redesign of the marketing, distribution, product design, new business, operations and servicing can occur with these changes in mind.

Reasons for optimism

Despite the bleak picture we have painted so far, we believe that reinventing life insurance and redesigning its business model are possible. This will require fundamental rethinking of value propositions, product design, distribution and delivery mechanisms and economics. Some of the most prescient insurers are already doing this and focusing on the following to become more attractive to consumers:

Reasons for optimism

Despite the bleak picture we have painted so far, we believe that reinventing life insurance and redesigning its business model are possible. This will require fundamental rethinking of value propositions, product design, distribution and delivery mechanisms and economics. Some of the most prescient insurers are already doing this and focusing on the following to become more attractive to consumers: