We are in the midst of a bionic revolution in all industries and especially insurance. Organizations are competing with a new mix of people and machines doing both cognitive and physical work, and those companies that become bionic fastest are winning because of superior customer experience and economics. This has led to a new Digital Darwinism — the evolution of businesses and business models that not only occurs across generations as it does in the natural world, but rapidly and many times within the lifetime of a single organization.

The speed of evolution creates imbalances — and in the insurance industry we see a sophisticated sales/distribution experience with an old-style issuance, service and claims experience. Until very recently, insurtech has been a story of front-end evolution. It is only now that enterprise investments in insurtech have matched the front-end.

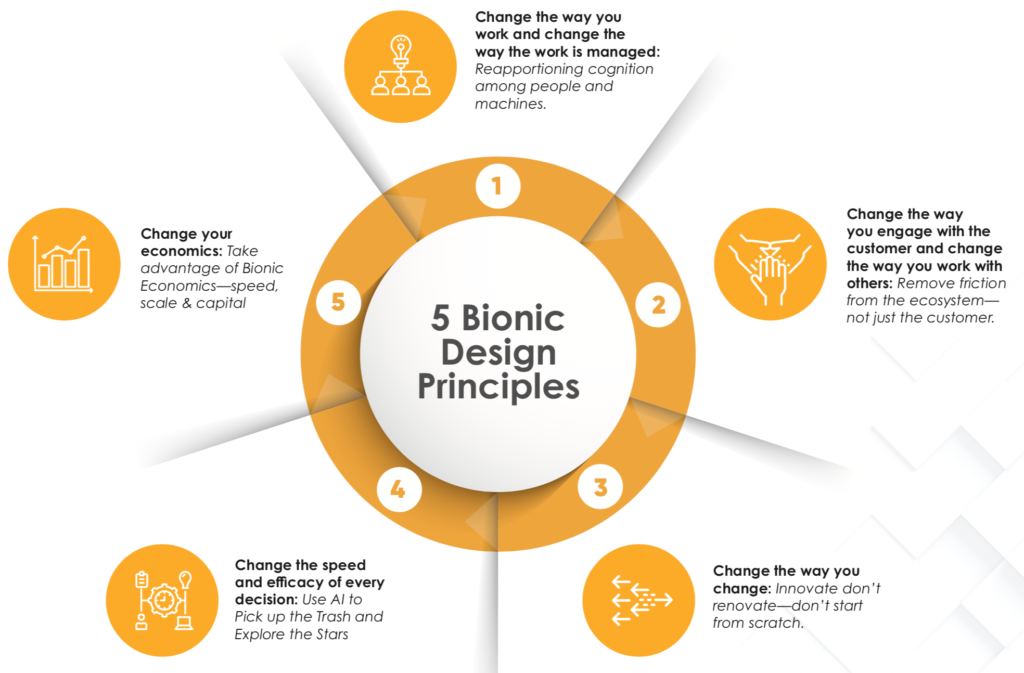

How do you increase the clock-speed of your evolution? Our lens at Snapsheet is to collectively reimagine the operating model, operational capabilities and customer experience with five bionic design principles in mind. A design principle is a practical concept that helps executives imbue the organization with the right way to think about critical tradeoffs and solutions. For example, Steve Jobs hated styluses, so the iPhone created a user interface that did not need any type of stylus. This simple concept drove many actions in Apple.

Bionic Design Principle 1: Change the way you work, and change the way the work is managed: Reapportion cognition among people and machines.

The fundamental activity of the industrial revolution has been to take thinking and labor tasks “out” of people and put them “into” machines. It’s a one-way street optimized around one process, one answer, one method. In contrast, in the bionic age, everything has the potential to be smart. Processes can be agile; claims can be alive and know their own path and what data they need to complete their task. Claims can even be patient, knowing how long information requests should take and when it’s time to “ask again” for missing information. A claim can even route itself to the optimal process and resources using its understanding of its complexity, service level status, skills needed and available, licensing requirements or other attributes; for example, a claim can know if it’s a total loss auto claim and therefore has a shorter, faster process path.

This dynamic allocation of cognitive responsibilities is the most important design principle because its application allows for the entire claims ecosystem (or any ecosystem) to be better without having to be in full control of every step. For example, to implement our smart claim approach in auto, we do not require customers to choose the way they engaged with us or others. Rather, we allow the customer to choose and change the interaction mechanisms, and the claim learns how the specific customer or repair shop interacts and how long responses take. The claim acts accordingly. The process is not industrial and stringent, but bionic and adaptive.

When cognition is reapportioned, no time is lost, and actions are optimized against capacity—and as the system gets smarter it can evolve the process and support higher and higher level tasks. The design itself does not have to be all-knowing right out of the gate. It masters a specific challenge and evolves over time because it’s a living system, not a mechanistic one.

See also: Darwinian Shift to Digital Insurance 2.0

Advanced weapons systems in fighter aircraft have shared thinking responsibilities with pilots for many years. Sometimes the pilot is flying the plane, and the weapons system is protecting the plane; other times, the plane is flying itself, and the pilot is focusing on the weapons systems. This dynamic allocation of cognition means that the most capable thinker—person or machine—will be in charge based on context and competence, not rigid process. Think of claims as thinking for themselves: Each claim also knows when to “ask for help” and push the activity to a human when the claim lacks enough data, structure and rules to proceed. This adaptability enables productive integration of the complex, digitally enabled ecosystems that all insurers face. Put another way, it’s not just machine learning, it’s a learning machine.

Bionic Design Principle 2: Change the way you engage with the customer and change the way you work with others: Remove friction from the ecosystem—not just the customer.

Customers no longer tolerate friction. They want service anywhere, anytime, any way — and expect to have instantaneous status about every step of the process. In claims, the old way was to send out a person to look at the vehicle or visit the home. But if you’re creative, you can change the flow. We began Snapsheet by inverting the process—enabling customers to use their smartphones to send in photos of their accident so they could poll repair shops to deliver virtual estimates, instead of having a person visit the scene of the accident—thus removing a friction point and saving time. But as we implemented this innovation, we saw that we needed to do more. Some customers were not confident in their ability to take the right photos or did not want to use an “app”—so we had to enable omnichannel capture, allowing the customer to begin the process in any way the customer found faster or easier.

We’ve been chasing friction removal for seven years, and we expect to continue chasing it. It’s easy to say that “it’s not just about the technology,” but turning that observation into less friction for the customer takes a willingness to learn, adjust, reintegrate and sometimes reinvent major functions across the ecosystem.

Our ability to field smart claims that are aware of their context enables us to see how to close the gap between the desire and realization that happens in many places in the claims ecosystem. By looking at the whole ecosystem, not just the individual task, you can see entire areas of opportunity open up.

For example, we found that making payments—more than 75% of them still transacted by paper check—was an area we could redesign. Now we have the ability to provide payment and treasury functions instantaneously for all parties involved as soon as a step in the process—such as repair—is verified as complete. We asked participants in the ecosystem, “Do you want to get paid fast or slow?” No surprise, most customers say, “Fast!”

Another significant delay often comes from processing a total loss situation, which is often slowed by the complexity of issues having to do with identifying the lien holder of the asset and the title procurement process in a specific geography. This complexity requires a carrier to change the way it engages with other suppliers. In this case, working with other industry partners, Snapsheet is enabling faster exchange of information across multiple parties, initiating insurance and salvage workflows simultaneously and integrating new capabilities to remove that friction. In doing so, it’s possible to remove days, and even weeks from the process. This accelerates the time to sell the vehicle for the insurer and time to settlement for the customer.

Bionic Design Principle 3: Change the way you change: Innovate, don’t renovate—don’t start from scratch.

The most critical part of digital evolution is to change how you change. The idea of continuous improvement has been with us for many years—at least since the 1950s when Edward Deming led the quality movement. Most insurance companies have done an analysis of what it takes to redo the entire technology stack—and it is often an absurd number with millions and millions of dollars at risk for an uncertain payoff.

Fortunately, there are many new tools to help enable integration of legacy and emerging systems. The suites of robotic process automation tools help to provide what we call value-driven integration. When companies use these products or other integration/automation tools, they can often integrate multiple legacy systems with a secure container that can interface with multiple systems and then present the results on any device—providing new results, without the need for complete system overhauls or upgrades. This creates productive modules—of process, task and technology—together, which enables improvement with zero down time while delivering continuous enhancements.

With new API architectures, one can partition the work and make it more object-oriented, which enables more flexible task and process flow design within the organization and outside to suppliers. Properly used, this creates a much more agile and adaptable learning environment.

This can take time out of customer service, sales or other interactions by collapsing many dozens of steps and multiple screens over hours, to one screen and minutes, while kicking out a clean stream of audited data for machine learning to drive future improvement. This capture of cognitive capital drives near-term labor productivity and superior customer experience while providing a data asset for further improvement. Especially in the middle and back office, there are often greater opportunities to drive customer experience and superior economics.

See also: A Self-Destructive Cycle in Insurance

Again, in the bionic age, the right way to think of it is as smart, evolving, alive systems. The most important design decisions are about the application program interfaces (APIs) and the modularity of the system. For example, Jeff Bezos declared that Amazon would use common APIs back in the early 2000s, which meant that the company could add or subtract functionality without interfering with the existing process and code base of the organization. This means the company can handle complexity at a much lower unit cost because complexity is contained within the modules. This is not true of many of his competitors, and you only need to go into Macy’s and try to find your order history with the store, to show the lack of APIs in that organization.

The innovate-not-renovate point of view relies on modular thinking. This may seem incremental to some, but some of the most important innovations in human history have been integration technologies that enable established ecosystems to interact productively. The international currency markets are such an innovation; so is the internet, whose very name states its “inter-networking” mission. In the bionic world the biggest bang for the buck is usually in innovating and integrating existing ecosystems, not starting from scratch.

Bionic Design Principle 4: Change the speed and efficacy of every decision: Use AI to pick up the trash and explore the stars

Evolution is often a process of simple and complex improvement. The fourth design principle is to use AI both for the low and the high end.

On the low end, AI helps to automate faster because it can gather new information and structure it faster. There are many mundane tasks that AI can help to improve. Proper analysis of photographs is a great example, and we have developed more and more capability to make sure we have the right angle and proper picture needed to move the claim forward in the process. Even simple uses of AI such as this can add up to vast improvements in speed and productivity.

On the high end, we are developing complex models that can continue to automate and refine estimates for more and more severe accidents. This other use of AI is like a telescope for the mind—allowing new insights into vast data sets and complex problems that would not be possible without it. We analyze millions and millions of accident pictures that feed a super-smart estimating engine and leverage our estimator talent eight to one compared with non-assisted, experienced estimators. We are also finding interesting patterns in repair shops, types of accidents, customer behavior etc. If we did not have the massive and growing scale of transactions, we would not have seen and been able to share these insights.

Bionic Design Principle 5: Change your economics: Take advantage of bionic economics— speed, scale & capital

Perhaps the most powerful force of Digital Darwinism is the speed of change in core economics. This is why our final key design principle is to use the business system with the best total economics, driven by speed, scale and new forms of capital. There is no question that this new mix of people and machines can make decisions faster. We’ve found that our staff are as much as five times as productive, but they are not super humans; they are simply people supported by great cognitive technology and training. The more data and transactions that any learning machine can ingest, the better its speed and accuracy.

Google Translate is so good because it was fed with billions of books and all the proceedings of the E.U., which publishes in about three dozen languages. This vast wealth of data made it learn faster. So, too, with claims. This speed not only decreases labor, it also allows us to provide answers faster and get through the entire process in less time. In claims, like many things in life, time only makes things worse— with impatient claimants creating additional service demands and the organization incurring added costs such as rental and storage.

In terms of scale, larger networks of computer power usually have superior economics. The cloud not only enables organizations to make their costs more variable, (e.g., if you need more capacity, simply contract for more without the need to buy new hardware and software) but also provides the ability to take advantage of the economics that support that network—such as the formidable buying power of the cloud provider, power efficiency, customized operating systems and software that creates other efficiencies. There are many end points on the network—another scale effect. Why do people usually go to Google? Because its network of links is larger and better than the competition. Why go to the second-best network? Likewise, cloud providers of critical business functions can create a world-scale network that is larger and better than all but the largest individual competitors.

Lastly, the bionic competitors gather and grow three types of capital: behavioral, cognitive and network.

Behavioral capital is the ability to track, analyze and model the behavior of any customer, device or service provider in the ecosystem. United Rental has over 70% of its assets—going to 100%—linked so the company can see the location, behavior and maintenance status of all assets. This is behavioral capital.

Cognitive capital is the store of AI, algorithms and other automated knowledge that can be used, improved and reused again and again. The better the store of cognitive capital, the more organizations can leverage existing labor and assets.

Network capital is how well a company is tied into the relevant networks for customer and supplier access. For example, no consumer products company can afford to not have a strategy for Amazon and Alibaba because they have some of the most extensive network capital in the world for consumer products. In bionic competition, organizations need to strategically use cloud providers that can bring these new forms of capital to bear to create superior economics.

There you have it. Five design principles that you can add to your strategy to move beyond siloed activities and on the way to deep transformation— speeding up your evolutionary process to meet the needs of a new Digital Darwinism and updating your customer’s experience along the way.