Our three U.S. venture-backed nsurtech carriers have mo' money, mo premiums' and mo' losses. Around the time their losses became notorious, there were some signs of improvement, but not enough to prove viable business models. It’s still early. No 2Pacalypse is imminent, as the startups have tons of cash. But forget about East Coast/West Coast feuds: It’s still insurtechs against the world.

- Premiums and losses grow at venture-backed startups

- Industry-backed startups stay focused on underwriting

- Gross or net – which matters?

- Correcting rookie mistakes, experimenting and still underpricing?

- Can anyone beat Progressive and Geico?

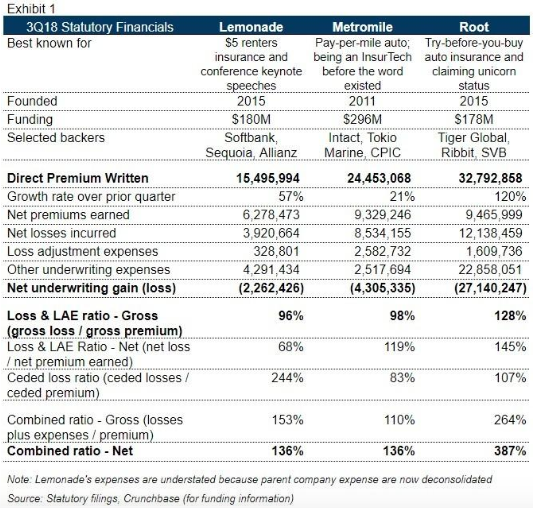

Context This is the fourth installment of our review of U.S. insurtech startup financials. Here are the 2017 edition, the first quarter 2018 edition, which generated many social media discussions, and the second quarter 2018 edition. For more information on where our data come from and important disclaimers and limitations, see the 2017 edition. As we have said since the start, we think all three companies have solid management teams who will figure out a solid business, but it will take time.  1. Premium and losses grow at venture-backed startups As we have said before, it’s early days. Growth is rapid. But all three startup carriers are a long way from profitability and need to continue to raise prices substantially (and thus potentially churn customers), tighten underwriting (which could also materially affect growth) or improve operational aspects that drive losses such as claims performance. In insurance, product-market fit is only demonstrated when selling a product that makes money. Here is the summary of the 3Q18 details of the three venture-backed U.S. insurers that we’ve been tracking. The fourth venture-backed insurer, Next Insurance, did not write premium in 3Q18.

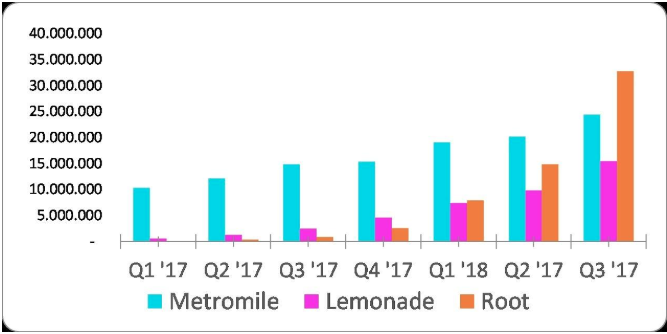

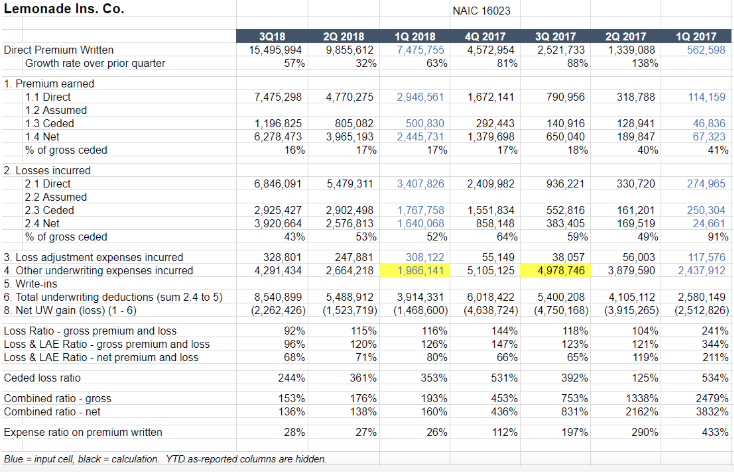

1. Premium and losses grow at venture-backed startups As we have said before, it’s early days. Growth is rapid. But all three startup carriers are a long way from profitability and need to continue to raise prices substantially (and thus potentially churn customers), tighten underwriting (which could also materially affect growth) or improve operational aspects that drive losses such as claims performance. In insurance, product-market fit is only demonstrated when selling a product that makes money. Here is the summary of the 3Q18 details of the three venture-backed U.S. insurers that we’ve been tracking. The fourth venture-backed insurer, Next Insurance, did not write premium in 3Q18.  On expenses, it is important to note that Lemonade received permission from New York State to hide some expenses in an affiliated entity effective at the start of this year, so Lemonade’s expenses aren’t comparable to the others. (Lemonade’s CEO told us that the State of New York requested the change.) Root has followed suit and will now start to hide expenses in an affiliated agency, effective Oct. 1, 2018. Unfortunately, with less transparency, it is harder to verify whether the overall business model actually adds up. Lemonade, for example, makes a big deal about the power of an insurer built on a “digital substrate.” We’re inclined to agree, and we hope they’re right, but we won’t know from their statutory results whether a better expense ratio is really possible. *** The third quarter’s “most improved” award goes to Lemonade, which grew premium by 57% over the prior quarter to $15.5 milliion (perhaps helped by seasonal effects in the rental market) AND turned in a 96% gross & LAE loss ratio, its best ever. The company's reserves developed slightly adversely in the quarter, with YTD unfavorable development standing at $254,000, modestly worse from $245,000 the prior quarter.

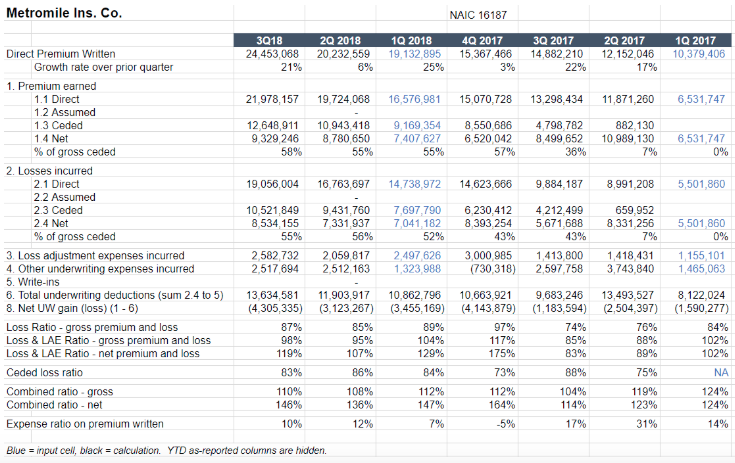

On expenses, it is important to note that Lemonade received permission from New York State to hide some expenses in an affiliated entity effective at the start of this year, so Lemonade’s expenses aren’t comparable to the others. (Lemonade’s CEO told us that the State of New York requested the change.) Root has followed suit and will now start to hide expenses in an affiliated agency, effective Oct. 1, 2018. Unfortunately, with less transparency, it is harder to verify whether the overall business model actually adds up. Lemonade, for example, makes a big deal about the power of an insurer built on a “digital substrate.” We’re inclined to agree, and we hope they’re right, but we won’t know from their statutory results whether a better expense ratio is really possible. *** The third quarter’s “most improved” award goes to Lemonade, which grew premium by 57% over the prior quarter to $15.5 milliion (perhaps helped by seasonal effects in the rental market) AND turned in a 96% gross & LAE loss ratio, its best ever. The company's reserves developed slightly adversely in the quarter, with YTD unfavorable development standing at $254,000, modestly worse from $245,000 the prior quarter.  Lemonade has a ways to go -- its reinsurers continue to subsidize the loss ratio (but now paying "only" $2.44 of losses per dollar of premium), the average net loss & LAE ratio is still well above the 40% at which charities receive a giveback, and the company is far from profitability. But re-underwriting and higher rates -- which we discussed in our last post -- may be paying off. There are other explanations, too -- shifting to cat-exposed risk, for example, lowers the loss ratio but raises the cost of capital. See also: Insurtech: Revolution, Evolution or Hype? The company has written $33 million in the first nine months of 2018, which is well behind some exponential expectations published last year. Management also says that they will take out 60 loss ratio points: "A similar progression in the year ahead will get us to where we need to be." Good luck. (Despite the good quarter.) Taking out loss ratio points gets harder for every point you get closer to the industry average. The breeziness of management's comments makes us wonder how much focus will be placed on the hard spadework of loss ratio improvement vs. embarking on a glamorous European Grand Tour. Respected industry analyst V.J. Dowling, whose IBNR Weekly publication (subscription only) was cited in a Lemonade transparency blog supposedly praising Lemonade, recently published a tear-down of Lemonade's strategy. IBNR called the giveback “a joke,” the company's marketing "overly simplistic, constantly changing and borderline dishonest" and “B.S. On Lemonade’s 'Transparency' & Model." We have long taken issue with Lemonade’s definition of “transparency,” which (as with many startups) is transparent only insofar as the company wishes to tell a story, which is just another form of marketing. (We are working on a longer article about ways startups bend numbers and welcome your ideas). We also agree with IBNR that a giveback at 1.6% of premium seems cynical. Middle-class insurance agents are some of the biggest charitable donors and sponsors in many towns, and it’s hard to see the social benefit in Lemonade’s spending the advertising budget enriching amoral tech bros at GAFA rather than sponsoring the town's Little League uniforms as an agent might do. Even insurance veterans don’t seem to realize that all of Lemonade’s entities are for-profit. Don't be fooled: B-Corps are still for-profit corporations. And railing against gun violence is easy, but social consciousness is messy in reality. Metromile grew at a steady and respectable 21% from the prior quarter to $24.5 million of gross premium but ran a 98% gross loss & LAE ratio (not improved from 2017). Among the three players, it has been the ant: slower growth and rather steady results. After seven years in business, the company is barely generating an underwriting profit and is showing little improvement. The company has been taking rate, but not as much as the actuaries say is needed. The company’s latest California indication, for example, is rates up 38%, but the company only took 15 points of rate, effective July 1, 2018, which will work through its book over the next couple of months. Matteo recently published a discussion of why its PAYD (the pay-as-you-drive) approach confirms its niche nature.

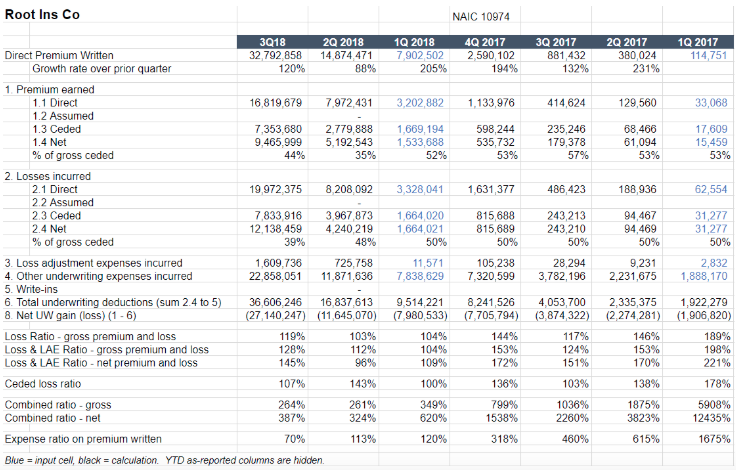

Lemonade has a ways to go -- its reinsurers continue to subsidize the loss ratio (but now paying "only" $2.44 of losses per dollar of premium), the average net loss & LAE ratio is still well above the 40% at which charities receive a giveback, and the company is far from profitability. But re-underwriting and higher rates -- which we discussed in our last post -- may be paying off. There are other explanations, too -- shifting to cat-exposed risk, for example, lowers the loss ratio but raises the cost of capital. See also: Insurtech: Revolution, Evolution or Hype? The company has written $33 million in the first nine months of 2018, which is well behind some exponential expectations published last year. Management also says that they will take out 60 loss ratio points: "A similar progression in the year ahead will get us to where we need to be." Good luck. (Despite the good quarter.) Taking out loss ratio points gets harder for every point you get closer to the industry average. The breeziness of management's comments makes us wonder how much focus will be placed on the hard spadework of loss ratio improvement vs. embarking on a glamorous European Grand Tour. Respected industry analyst V.J. Dowling, whose IBNR Weekly publication (subscription only) was cited in a Lemonade transparency blog supposedly praising Lemonade, recently published a tear-down of Lemonade's strategy. IBNR called the giveback “a joke,” the company's marketing "overly simplistic, constantly changing and borderline dishonest" and “B.S. On Lemonade’s 'Transparency' & Model." We have long taken issue with Lemonade’s definition of “transparency,” which (as with many startups) is transparent only insofar as the company wishes to tell a story, which is just another form of marketing. (We are working on a longer article about ways startups bend numbers and welcome your ideas). We also agree with IBNR that a giveback at 1.6% of premium seems cynical. Middle-class insurance agents are some of the biggest charitable donors and sponsors in many towns, and it’s hard to see the social benefit in Lemonade’s spending the advertising budget enriching amoral tech bros at GAFA rather than sponsoring the town's Little League uniforms as an agent might do. Even insurance veterans don’t seem to realize that all of Lemonade’s entities are for-profit. Don't be fooled: B-Corps are still for-profit corporations. And railing against gun violence is easy, but social consciousness is messy in reality. Metromile grew at a steady and respectable 21% from the prior quarter to $24.5 million of gross premium but ran a 98% gross loss & LAE ratio (not improved from 2017). Among the three players, it has been the ant: slower growth and rather steady results. After seven years in business, the company is barely generating an underwriting profit and is showing little improvement. The company has been taking rate, but not as much as the actuaries say is needed. The company’s latest California indication, for example, is rates up 38%, but the company only took 15 points of rate, effective July 1, 2018, which will work through its book over the next couple of months. Matteo recently published a discussion of why its PAYD (the pay-as-you-drive) approach confirms its niche nature.  If Metromile is an ant, Root is a grasshopper. Root again grew extremely rapidly through its TBYB (Try-Before-You-Buy) mobile approach, as one probably would expect of a company with a $1 billion valuation (as we discussed in our previous article). Root doubled the volumes underwritten by Lemonade. But Root continues to struggle with rookie mistakes that drove losses -- discussed more below. Root grew premium by 120% vs. the prior quarter to $33 million for the third quarter but turned in 128% gross loss & LAE ratio - its worst of the year and the worst of the three U.S. insurtech carriers.

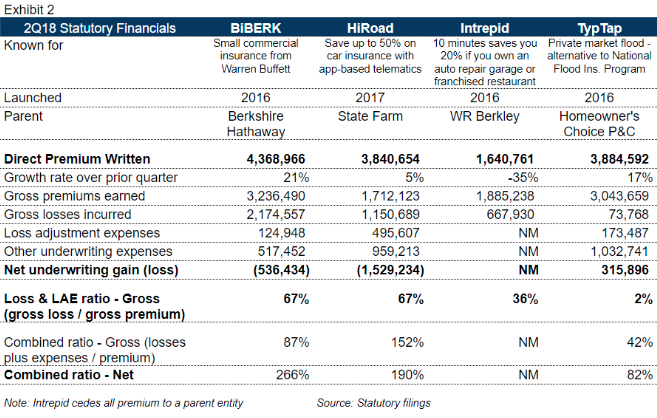

If Metromile is an ant, Root is a grasshopper. Root again grew extremely rapidly through its TBYB (Try-Before-You-Buy) mobile approach, as one probably would expect of a company with a $1 billion valuation (as we discussed in our previous article). Root doubled the volumes underwritten by Lemonade. But Root continues to struggle with rookie mistakes that drove losses -- discussed more below. Root grew premium by 120% vs. the prior quarter to $33 million for the third quarter but turned in 128% gross loss & LAE ratio - its worst of the year and the worst of the three U.S. insurtech carriers.  ** With the three carriers resuming rapid growth after a slow 2Q, the 2Q slowdown that we observed in our prior article may have been seasonal or a one-time coincidental slowdown. 2. Industry-backed startups stay focused on underwriting We first pointed out in the prior quarter’s analysis that companies run/led by well-known underwriters were growing slowly but were far more profitable than those with venture capital backing. That hasn’t changed. Here are the four subsidiaries of big companies that are selling direct or have a claim on being an insurtech. These companies often depend on parents for reinsurance and infrastructure, so we show mainly the gross figures.

** With the three carriers resuming rapid growth after a slow 2Q, the 2Q slowdown that we observed in our prior article may have been seasonal or a one-time coincidental slowdown. 2. Industry-backed startups stay focused on underwriting We first pointed out in the prior quarter’s analysis that companies run/led by well-known underwriters were growing slowly but were far more profitable than those with venture capital backing. That hasn’t changed. Here are the four subsidiaries of big companies that are selling direct or have a claim on being an insurtech. These companies often depend on parents for reinsurance and infrastructure, so we show mainly the gross figures.  3. Gross or net - which matters? One well-regarded venture capitalist challenged us on why gross premiums and loss ratio matter when net is what actually sticks to current investors. The difference between gross and net is reinsured premium and loss. The gross loss ratio is provides an unbiased view of the profitability of the book of business, while the net loss ratio may benefit from savvy reinsurance buying, as in the case of Lemonade. See also: How Insurtech Helps Build Trust What matters most is for startups probably the higher of the two loss ratios. If reinsurance reduces the loss ratio, this is only sustainable over time if reinsurers make an adequate return. Reinsurers, like all businesses, tend to demand higher prices when customers lose them money, which in time makes the net loss ratio look more like the gross. In the case of the two auto startups, they are paying reinsurers to take away their biggest losses, so this “cost of reinsurance” needs to be reflected, and the net numbers matter more. 4. Correcting rookie mistakes, experimenting and still underpricing? At the Nov. 30 plenary session of the U.S. IoT Insurance Observatory, Denese Ross of DRC Consulting shared an in-depth 50-page review of Root’s filings, which total over 130,000 pages. Our opinions, based on her factual/non-opinion analysis, is that Root is experimenting aggressively, correcting some rookie mistakes and still underpricing some business.

3. Gross or net - which matters? One well-regarded venture capitalist challenged us on why gross premiums and loss ratio matter when net is what actually sticks to current investors. The difference between gross and net is reinsured premium and loss. The gross loss ratio is provides an unbiased view of the profitability of the book of business, while the net loss ratio may benefit from savvy reinsurance buying, as in the case of Lemonade. See also: How Insurtech Helps Build Trust What matters most is for startups probably the higher of the two loss ratios. If reinsurance reduces the loss ratio, this is only sustainable over time if reinsurers make an adequate return. Reinsurers, like all businesses, tend to demand higher prices when customers lose them money, which in time makes the net loss ratio look more like the gross. In the case of the two auto startups, they are paying reinsurers to take away their biggest losses, so this “cost of reinsurance” needs to be reflected, and the net numbers matter more. 4. Correcting rookie mistakes, experimenting and still underpricing? At the Nov. 30 plenary session of the U.S. IoT Insurance Observatory, Denese Ross of DRC Consulting shared an in-depth 50-page review of Root’s filings, which total over 130,000 pages. Our opinions, based on her factual/non-opinion analysis, is that Root is experimenting aggressively, correcting some rookie mistakes and still underpricing some business.

The following is Matteo & Adrian's interpretation and analysis:

- Raising rates, but is it enough? Root has begun correcting its early underpricing by raising rates substantially in several states, but not as much as the actuaries indicate is needed. The company has filed rate increases in seven of its 20 states since late summer, ranging from +5.5% to +34%. The highest is in Texas, where the filing is pending, and where Root now writes 1/3 of its premium (whereas Ohio was the largest state last year). The indication in Texas was +200%. An indication is the change to the overall rate “indicated” by an actuarial analysis to achieve a specified pricing target based on analysis and adjustments to historic trends. For many reasons, the rate level chosen could be less than the indication, but a big gap between rate taken and indication suggests management may still be oriented toward growth even if it is at a loss. Indeed, Root recently put up a blog post claiming to be up to 52% cheaper. Further, Root also added or changed discounts, which are not part of the headline rate. In other states, per-policy rate caps limit the actual amount of rate taken on renewal business, possibly to avoid churning existing customers, since the acquisition cost of a renewal customer acquired via a direct channel is quite small. These rate-making decisions illustrate the fine line a company like Root has to walk when balancing growth, profitability, retention and acquisition cost. Similarly, investors should be wary of individual numbers presented in isolation -- it can be good to churn underpriced customers.

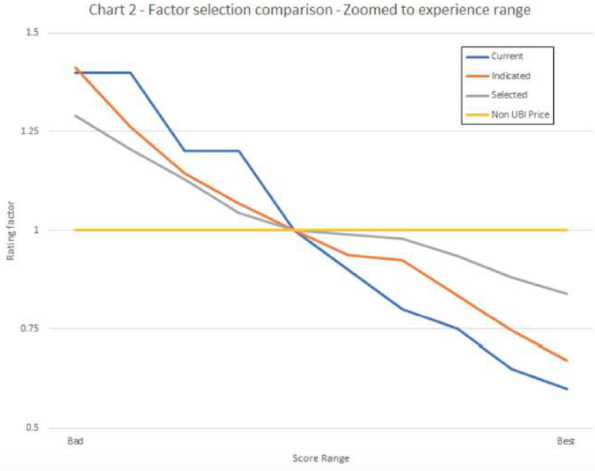

- Technology that isn’t as predictive as expected: Root collects telematic data via a smartphone and scores a driver once he or she has tracked 500 miles, using features such as hard braking, acceleration, turning, time of day, mileage, consistency and distractions. The company started with a third party's telematics model that apparently gave excessive discounts to drivers in better tiers – see the steep blue curve below, which is from a Root filing. Root then developed its own model and is giving more modest discounts to better drivers (gray line). Telematics contributes information and allows more granular clustering, but the law of large numbers and class rating variables (e.g. demographics) still matters more than perhaps anyone would like. Good drivers get hit by uninsured bad drivers. Bad drivers can drive well for 500 miles when they’re being watched. Good drivers’ cars get stuck in hail storms and hurricanes. Nonetheless, Root is the first insurer around the world to acquire large numbers of customers through a TBYB (Try-Before-You-Buy) app, something many incumbents have tried in the past few years.

- Me-too is harder than it looks. Root has filed several modifications to its rates to correct mistakes, such as correcting household structure data, moving from ISO vehicle symbols to factors assigned directly by VIN and correcting for “double-discounting” and “double-surcharging.”

- Claims difficulties. Most startups lack a high-quality claims infrastructure, which is one of the hardest aspects of an insurer to build, but it appears that Root is now taking more claims activity in-house instead of using a third party claims administrator (TPA). To date, Root's customer claims experience hasn't been as easy as the company says. The 15 Better Business Bureau complaints are mostly claims-related, and only 1/3 of Clearsurance users were satisfied with the claims experience. On the same website, Progressive and Geico are around 80%, and Metromile is at 70% claims satisfaction. As one Clearsurance review of Root reads: "I was in an accident back in July, and it's now November, and my simple simple claim has not been paid on or closed out. It was originally with an adjuster at Crawford & Co. but without my knowledge that changed hands to some other adjuster actually within Root. The original adjuster back in September said that she would get back to me within the week....Months later and I'm still here with an open claim."

It will take time for the corrections Root has made to show through in results. And particularly on pricing, they may be too little. Thus, the question remains: Is Root’s growth simply the result of selling something far too cheaply, or is it quietly experimenting its way to becoming the next Progressive? 5. Can a startup compete with Progressive and Geico? The most common refrain of startups is that insurance is broken, and their solution will fix it. Oui, c'est vrai. But two companies have their act together more than almost any other insurers: Geico and Progressive, the #2 and #3 auto insurers in the U.S. Geico is famous for its lean expenses, while Progressive runs a loss ratio about six points below the industry average of 69%. It wasn’t always this way. Back in 1996, Progressive was #7, and Geico was #9. There are few other examples in insurance of companies so steadily and regularly gaining market share across decades. In our first article, we showed how startups historically have only won where incumbents leave the door open. Progressive and Geico are not leaving the door open, at least in personal auto as a stand-alone line. Progressive, in particular, has been quite experimental throughout its life, pioneering telematics in the U.S. and experimenting with various ways of paying for auto insurance and using telematics, as some startups are now doing, but with none of Progressive’s advantages. So why do startups try to compete with such well-run companies? We think there are several beliefs (or hopes):

- A belief that the startup can duplicate public filings to set rates. As noted above, it's harder than it looks. Even professional comparison rating websites have trouble estimating a person's actual premium, and, in a thin-margin business, small differences matter. This is not a new story – eSurance's first me-too nearly 20 years ago didn't work particularly well. Progressive, having outperformed the market for decades, knows that its filings are scrutinized. Like a game of cat and mouse, the company has become expert at fooling competitors that try to replicate filings, which run thousands of pages and are deliberately obscured and complicated. And rate filings are only one aspect of underwriting. Credit models, underwriting rules and marketing plans for attracting the best customers may not be public and may be difficult to replicate. The result is that unwary and inexperienced competitors may grow by unknowingly writing the risks that their competitors didn’t want. There is no CAC at which an underpriced customer is a desirable customer

See also: Insurtech’s Act 2: About to Start

- A belief that there are profitable untapped segments that incumbents won’t cannibalize. Progressive and Geico are very intelligent companies with a long history of innovation and extremely detailed customer segmentations. It defies all logic to suggest that there is a large segment of customers in a fragmented and highly competitive market that are being greatly overcharged simply because these companies refuse to offer them good rates to avoid cannibalization.

- A belief that the startups can easily acquire customers through direct channels. Direct distribution is not new in U.S. auto – Geico and Progressive both spend billions of dollars a year in advertising and have extremely sophisticated digital marketing. To this end, one of Root’s interesting innovations is its referral program, which we showed in our last article to be quite powerful. (And we probably underestimated its power, because we didn’t account for multi-car policies.)

- A belief that the startups can be “good enough” at claims. Scale matters in handling claims, whether it is hiring and managing high-quality defense counsel, detecting fraud patterns or negotiating with vendors such as garages and roadside assistance services. Further, incentives for third party administrators must be carefully set to avoid excessive claims cost and customer dissatisfaction. For example, when a TPA is paid per open claim, speed of settlement may suffer, which can lead to regulatory fines or bad faith judgments – not to mention customer annoyance. In an industry where 96% is considered a best-in-class combined ratio, even a little bit of claims leakage can be quite hurtful. Metromile is exploring the reinvention of the claims process through the usage of telematics data. Considering the international best practices of doing this, the size of the portfolio might not allow the company to have enough claims yet to train an algorithm for a reliable crash kinematic reconstruction.

- A belief that “we only need 1% of a $220 billion market to be huge.” So 1999…

This analysis isn’t to suggest that it’s impossible for a startup to win in auto insurance, but that the moat around Geico and Progressive in personal auto is wide and deep. Conclusion The annual figures that are published in March contain a wealth of additional information. To be notified when these numbers are available, please follow the authors on LinkedIn.