$1 Million Reward to Show Wellness Works

We'll settle the wellness debate the old-fashioned way: offering a $1 million reward to anyone who can prove it isn't a horrible investment.

We'll settle the wellness debate the old-fashioned way: offering a $1 million reward to anyone who can prove it isn't a horrible investment.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Al Lewis, widely credited with having invented disease management, is co-founder and CEO of Quizzify, the leading employee health literacy vendor. He was founding president of the Care Continuum Alliance and is president of the Disease Management Purchasing Consortium.

Contrary to myth, option programs create competitive pressures that reduce workers’ comp costs and benefit both large and small employers.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Bill Minick is the president of PartnerSource, a consulting firm that has helped deliver better benefits and improved outcomes for tens of thousands of injured workers and billions of dollars in economic development through "options" to workers' compensation over the past 20 years.

Artificial intelligence can create natural dialogue with customers, nurture those leads, prioritize them for agents and follow through.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Jeff To is the insurance leader for Salesforce. He has led strategic innovation projects in insurance as part of Salesforce's Ignite program. Before that, To was a Lean Six Sigma black belt leading process transformation and software projects for IBM and PwC's financial services vertical.

Elements of medical care in the U.S. just plumb confound me. One is the requirement of a prescription for the most mundane of items.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Bob Wilson is a founding partner, president and CEO of WorkersCompensation.com, based in Sarasota, Fla. He has presented at seminars and conferences on a variety of topics, related to both technology within the workers' compensation industry and bettering the workers' comp system through improved employee/employer relations and claims management techniques.

Telematics is seen as a maturing technology, but there is still an untapped area: It can make processing claims much more efficient.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Monique Hesseling is a partner at Strategy Meets Action, focused on developing effective roadmaps and helping companies expand their business opportunities. Recognized internationally for her knowledge and expertise, she is assisting SMA customers across the insurance ecosystem.

Insurance agents need to have a discussion with their clients about their use of staffing companies and temps, especially in California.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Marjorie Segale is the Founder and President of <a href="http://www.segaleconsulting.com/">Segale Consulting Services, LLC</a> and provides a wide variety of services to the insurance industry, including account review, agency audits, strategic planning, and forensic claims analysis. Ms. Segale is also a principal and founding member of the <a href="http://www.insurancecommunitycenter.com/">Insurance Community Center, LLC</a>, a web-based resource and education on-line site for the insurance industry.

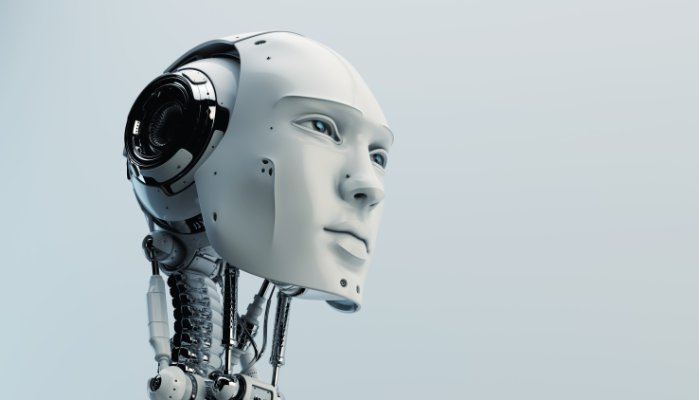

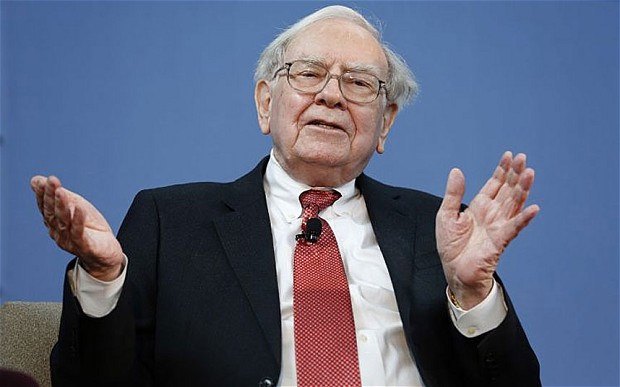

Buffett's timeless advice, over 38 years of writing to shareholders, includes: Uncertainty is okay as long as the price is right.

But all is not lost. Uncle Warren has written extensively about the insurance industry through letters to the shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway, which he has published every year since 1977. All this wisdom is available to anyone online for free, or you can even buy a printed copy. All you need is the nerdiness, dedication and patience to read through all 763 pages of material.

Because we know you’re busy, and don’t have the time to do this, we did it for you. We went through all 38 years of Warren Buffett’s letters, and we extracted everything you need to learn about insurance from the Oracle of Omaha himself, largely in his own words, with some of our colorful commentary. There is a lot to learn from Omaha’s Oracle, so instead of overwhelming you with all 38 years worth of knowledge, InsNerds will be publishing a series of articles sharing his wisdom.

The letters contain a lot of the history of GEICO, Gen Re, Berkshire Specialty Insurance and his other insurance companies in the letters; we chose not to include that and instead focus on insurance knowledge that can be useful to today’s insurance professionals. Uncle Warren keeps hitting many of the same points over and over; in those cases, we generally chose the wording from the newest letters, because, like good wine, Uncle Warren’s writing got better with time. Our first article will share three insights on the fundamentals of insurance:

But all is not lost. Uncle Warren has written extensively about the insurance industry through letters to the shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway, which he has published every year since 1977. All this wisdom is available to anyone online for free, or you can even buy a printed copy. All you need is the nerdiness, dedication and patience to read through all 763 pages of material.

Because we know you’re busy, and don’t have the time to do this, we did it for you. We went through all 38 years of Warren Buffett’s letters, and we extracted everything you need to learn about insurance from the Oracle of Omaha himself, largely in his own words, with some of our colorful commentary. There is a lot to learn from Omaha’s Oracle, so instead of overwhelming you with all 38 years worth of knowledge, InsNerds will be publishing a series of articles sharing his wisdom.

The letters contain a lot of the history of GEICO, Gen Re, Berkshire Specialty Insurance and his other insurance companies in the letters; we chose not to include that and instead focus on insurance knowledge that can be useful to today’s insurance professionals. Uncle Warren keeps hitting many of the same points over and over; in those cases, we generally chose the wording from the newest letters, because, like good wine, Uncle Warren’s writing got better with time. Our first article will share three insights on the fundamentals of insurance:

1. At the core, insurance is nothing but a promise, and being able to fulfill that promise is key:

“The buyer of insurance receives only a promise in exchange for his cash. The value of that promise should be appraised against the possibility of adversity, not prosperity. At a minimum, the promise should appear able to withstand a prolonged combination of depressed financial markets and exceptionally unfavorable underwriting results. ” 1984 letter, page 10.

Buffett is indicating that a company must be cognizant of the promise that it is making to its customers, which is that the company will have the funds to indemnify its customers after a loss. The company must manage its reserves and investments wisely to be able to fulfill its promise when there is a claim, so the investments must be able to withstand a down market and a year of catastrophic losses at the same time. One of the main things that makes insurance interesting is that, contrary to most other businesses, we don't know the cost of our product when we sell it.

2. Uncertainty is okay, as long as it's priced appropriately:

“Even if perfection in assessing risks is unattainable, insurers can underwrite sensibly. After all, you need not know a man’s precise age to know he is old enough to vote nor know his exact weight to recognize his need to diet.” 1996 letter, page 6.

The purpose of insurance is to manage risk. When taking on a given risk, it is not possible to know if you will see a positive or negative outcome. In choosing risks, one must make informed decisions, but if a company waits to make a decision it may lose the business. Insurers must determine how much uncertainty they are comfortable with. The company will likely not be able to attain every single bit of information that it would like before making a decision, but a decision must still be made.

3. Always remember the big picture:

“[…]any insurer can grow rapidly if it gets careless about underwriting.” 1997 letter, page 8.

Finally, in the business of insurance, a company should take on smart risks. It can be tempting to grow rapidly by writing any piece of business that comes your way. A company may take shortcuts in underwriting to put business on the books. However, if this practice becomes a habit, the profitability of your book will be unsustainable. Playing the long game is necessary in our business. This is something Uncle Warren is constantly talking about in his letters: Underwriting discipline, especially when the market gets soft, is his top priority.

These are three key observations about the basics of insurance that we found in reading Mr. Buffett’s letters. There are many more to be discovered, and we look forward to writing about some additional themes.

1. At the core, insurance is nothing but a promise, and being able to fulfill that promise is key:

“The buyer of insurance receives only a promise in exchange for his cash. The value of that promise should be appraised against the possibility of adversity, not prosperity. At a minimum, the promise should appear able to withstand a prolonged combination of depressed financial markets and exceptionally unfavorable underwriting results. ” 1984 letter, page 10.

Buffett is indicating that a company must be cognizant of the promise that it is making to its customers, which is that the company will have the funds to indemnify its customers after a loss. The company must manage its reserves and investments wisely to be able to fulfill its promise when there is a claim, so the investments must be able to withstand a down market and a year of catastrophic losses at the same time. One of the main things that makes insurance interesting is that, contrary to most other businesses, we don't know the cost of our product when we sell it.

2. Uncertainty is okay, as long as it's priced appropriately:

“Even if perfection in assessing risks is unattainable, insurers can underwrite sensibly. After all, you need not know a man’s precise age to know he is old enough to vote nor know his exact weight to recognize his need to diet.” 1996 letter, page 6.

The purpose of insurance is to manage risk. When taking on a given risk, it is not possible to know if you will see a positive or negative outcome. In choosing risks, one must make informed decisions, but if a company waits to make a decision it may lose the business. Insurers must determine how much uncertainty they are comfortable with. The company will likely not be able to attain every single bit of information that it would like before making a decision, but a decision must still be made.

3. Always remember the big picture:

“[…]any insurer can grow rapidly if it gets careless about underwriting.” 1997 letter, page 8.

Finally, in the business of insurance, a company should take on smart risks. It can be tempting to grow rapidly by writing any piece of business that comes your way. A company may take shortcuts in underwriting to put business on the books. However, if this practice becomes a habit, the profitability of your book will be unsustainable. Playing the long game is necessary in our business. This is something Uncle Warren is constantly talking about in his letters: Underwriting discipline, especially when the market gets soft, is his top priority.

These are three key observations about the basics of insurance that we found in reading Mr. Buffett’s letters. There are many more to be discovered, and we look forward to writing about some additional themes.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Tony Canas is a young insurance nerd, blogger and speaker. Canas has been very involved in the industry's effort to recruit and retain Millennials and has hosted his session, "Recruiting and Retaining Millennials," at both the 2014 CPCU Society Leadership Conference in Phoenix and the 2014 Annual Meeting in Anaheim.

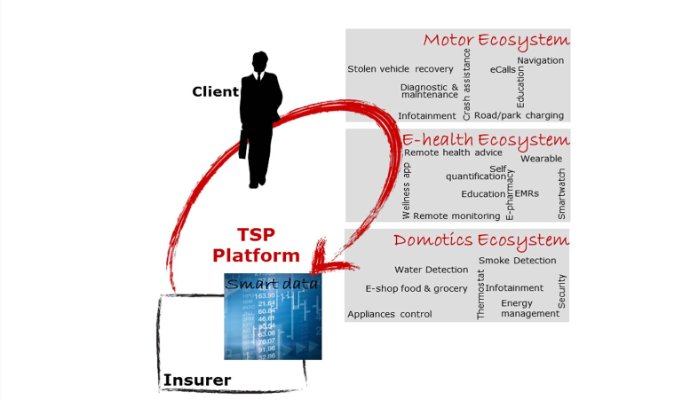

Numerous Fintech newcomers, building on the telematics model for autos, are taking dead aim at the health and home insurance markets.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Matteo Carbone is founder and director of the Connected Insurance Observatory and a global insurtech thought leader. He is an author and public speaker who is internationally recognized as an insurance industry strategist with a specialization in innovation.

Regrettably, organizations should anticipate that their carriers will deny claims under their cyber policies and must be ready.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Roberta Anderson is a director at Cohen & Grigsby. She was previously a partner in the Pittsburgh office of K&L Gates. She concentrates her practice in the areas of insurance coverage litigation and counseling and emerging cybersecurity and data privacy-related issues.

An industrywide coalition, MyPath, has formed to engage Millennials and get them excited about careers in insurance.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Alexander C. Vandevere serves as senior vice president of the Institutes and heads the strategic marketing department. Vandevere joined the Institutes in 2010 and was primarily responsible for the development of the Institutes Community—an online platform that enables professionals to stay connected with peers, the Institutes and the industry as a whole.