This article is an excerpt from a white paper, "Capturing Hearts, Minds and Market Share: How Connected Insurers Are Improving Customer Retention." In addition to the material covered here, the white paper includes specific recommendations on how to improve retention.

To download it, click here.

Insurers currently operate in a challenging environment. On the financial side, premiums are stagnant and interest rates low, and many cost-cutting measures have already been enacted. On the other hand, customer empowerment is growing. Customers are finding the information and offers they need to switch providers more freely than in the past - customers whom insurers can ill afford to lose.

For many carriers, the key to preserving customer relationships still lies in personal interaction, executed through traditional distribution and service models with tied agents and brokers. For some customer sets - those who strongly favor personal interaction - this business model works well. Yet a growing segment of customers, especially those 30 years old and younger, differ in some key aspects. While they still look for help and advice, they seek personal contact in the context of a holistic, omni-channel experience; they communicate and find information whenever, wherever and however they want. And even traditional customers appreciate if their agents have broader and faster access to the information and specialists they need on a case-by-case basis.

How can insurers keep - and even expand - these diverse customer sets, old and young alike? What factors drive retention and loyalty? To explore these questions, we surveyed more than 12,000 insurance customers in 24 nations about relationships with their insurers, what they perceive as valuable and in what ways they would like to interact and obtain new services going forward.

We found that while insurers understand well how to cover risks, they often fail to engage their customers on an individual basis. Even though insurance is complex, customers want to be involved, emotionally and rationally. When insurers act on this knowledge, customer share can rise.

The churn challenge

As a rule of thumb, the cost of acquiring new customers is four times that of retaining existing ones. To grow market share, insurers need new customers. But for the balance sheet, retention has a much larger impact.

For a long time, the insurance industry did not consider this lack of trust a problem. In the highly asymmetrical pre-Internet world, there was a necessary gatekeeper to information and knowledge about risks and coverages: the insurance intermediary. For insurers, the intermediary's trusted personal customer relationship was a guarantee of fairly reliable renewals and low customer churn - thus, keeping the most profitable customers.

The technological innovations of the digital age have altered this picture. Information asymmetry is diminishing. Although many customers still seek advice on insurance matters, the empowered digital customer does not need to rely solely on the gatekeepers of old for information. With communication being swift and ubiquitous, misinformation is quickly uncovered, leading to a steady erosion of trust, even with the personal adviser and insurer.

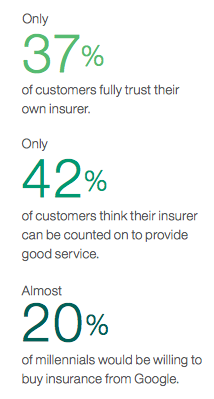

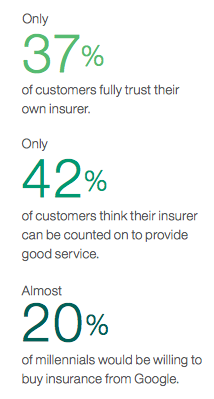

We have come to expect that only 43% of our survey respondents trust the insurance industry in general - a number that has stayed fairly stable since our first survey in 2007 - but only 37% trust their own insurers to a high or very high degree. Most customers are neutral, with 16% actually distrusting their providers.

As we have often seen in past studies, trust varies widely by market and culture. For example, only 12% of South Korean customers responded that they trust their insurers, compared with 26% in France, 43% in the U.S. and 51% in Mexico.

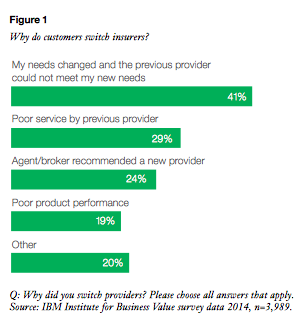

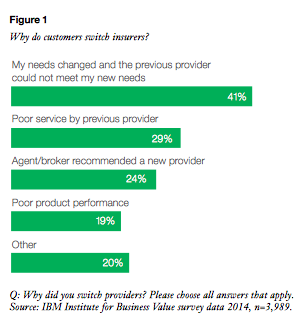

Low trust translates to high churn. Even though 93% of our respondents state that they plan to stay with their current insurers for their recently acquired coverage through 2015, almost a third came to that coverage by switching insurers. Why? Most commonly (for 41% of respondents), their old insurers couldn't meet their changing needs (see Figure 1).

The pattern of increasing customer empowerment and decreasing information asymmetry is continuing. New and non-traditional entrants to the insurance market are taking advantage of the opportunities of digital technologies. For example, Google recently launched an insurance comparison site for California and other regions of the U.S. This presents a real threat to both online insurers and traditional providers - not because of the comparison option itself, but because Google has collected a huge amount of information about each individual through his or her surfing habits, thus allowing better personalization and higher-value offers.

The three dimensions of retention

What do insurers need to do to increase trust and customer retention with the intent of improving both the top and bottom lines? The findings of our survey point to three courses of action:

- Know your customers better. Customer behavior is affected by experiences and underlying psychographic factors. Insurers need to know and understand customers better, not only as target groups but as individuals. Insurers also need to get their customers involved, rationally and emotionally.

- Offer customer value. As overused as the term is, a strong and individualized value proposition is exactly what insurers need to provide to their customers. Value is more than price; it includes many factors, including quality, brand and transparency.

- Fully engage your customers across access points. As Millennials become a significant part of the insurance market, speed and breadth of access has begun to matter much more than in the past. Insurers need to engage their customers as widely as possible, from in-person interactions at one extreme all the way to digital interaction models such as those made possible by the Internet of Things.

Customer perception and behavior

Ever since the Internet has become a viable way to shop for goods and services, much discussion has centered on the matter of price. In theory, insurance products are easy to compare, so shouldn't the cheapest one win out?

This view assumes that, aside from the price, all else is equal. If that were true, price would indeed be the sole tie-breaker. In reality, though, all else is never equal. Insurance is a product based on trust, for which perception matters. Perception, and thus customer behavior, is shaped by the individual customer's attitudes and experiences. Understanding a customer on an individual basis helps a carrier tailor these experiences by communicating the "right way."

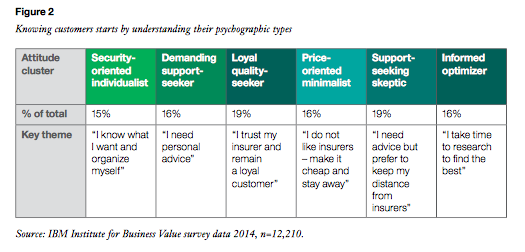

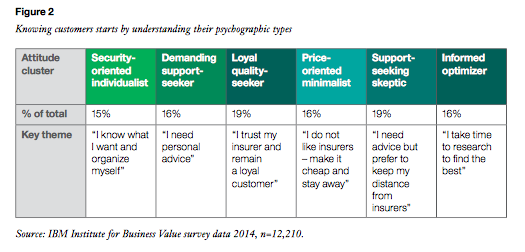

To classify our respondents according to their attitudes, we used the same psychographic segmentation as in previous studies (see Figure 2).

One size seldom fits all

Overall, our respondents stated that the three most important retention factors are price (63%), quality of service (61%) and past experience (33%) - leading back to the price as the main tie-breaker. Yet a closer look across segments paints a more diverse picture: For a demanding support-seeker, quality is by far the most important (74%), while a loyal quality-seeker bases his renewal intentions on past experience more strongly than any other group (43%).

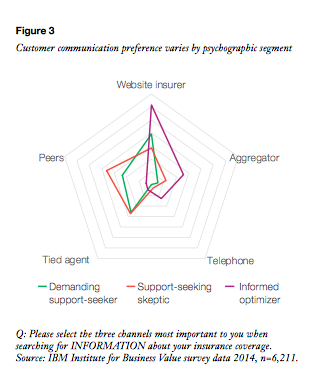

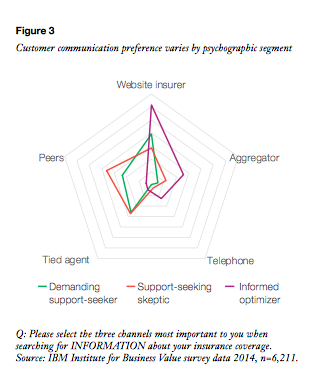

Assuming an insurer is targeting all these customer segments, it will need a diverse set of customer communication options, as each segment requires approaches tailored to its specific preferences (see Figure 3). This figure shows the five most-used insurance search options in the three segments where we are seeing the biggest shift among Millennials, who represent future customers.

The power of emotional involvement

Our data show that appropriate communication with customers sets off a positive chain reaction. First, it increased the use of that type of interaction. Customers perceived the interaction as more positive, and ultimately this increased emotional involvement with their providers - the "heart share" of our study title. Finally, emotional involvement is strongly connected to customer loyalty, so increasing involvement from medium to high had a dramatic impact on the loyalty index (see Figure 4).

What is the right way to communicate and increase involvement? As seen in Figure 3, the answer is "It depends," so there is no one right approach for all customers. But using current technology - specifically, social media analytics - can help insurers improve involvement.

With this tool, providers can "listen" to various online sources, understand how they are seen by customers, uncover trends and quickly tie this knowledge to specific actions. Providers can combine the findings of social media analytics with psychographic segmentation and an individual customer's place within the segmentation; the latter gained via more traditional customer analytics. With this customer view, insurers can even go beyond the personalized knowledge their tied agents tend to have: As customer wants and needs change and they articulate it on social channels, insurers will know and can react in close to real time.

Social media analytics

Social media analytics is a set of tools that allow insurers to analyze topics and ideas that are expressed by their actual or potential customers through social media. This can be on an individual basis, or per customer group. Through social media analytics, insurers can apply predictive capabilities to determine overall or individual attitude and behavior patterns, and identify new opportunities.

This article is an excerpt from a white paper, "Capturing Hearts, Minds and Market Share: How Connected Insurers Are Improving Customer Retention." In addition to the material covered here, the white paper includes specific recommendations on how to improve retention.

To download it, click here.