This keynote address was delivered to the EY/Insurance Insider's Global Re/Insurance Outlook conference at the Hamilton Princess Hotel in Bermuda.

It's a pleasure to be here this morning. I appreciate being invited to offer some thoughts on the state of our industry and where we seem to be headed.

If you'll indulge me for a few minutes, I'm going to look back at 2015 before I look forward to 2016. It feels like the right thing to do, given the year we've had.

I don't know about all of you, but for me 2015 has come and gone in the blink of an eye.

And what a year it's been.

You could invoke Dickens and say: It was the best of times. It was the worst of times.

This was the year that a youthful head of state swept into office in Canada on a promise of "sunny ways" - and it was the year that terror ripped through a nightclub in Paris, and a Christmas party in San Bernardino, CA, shattering our personal sense of security.

It was the year that the pope declared a Holy Year of Mercy, and it was the year that more than a million refugees streamed out of the Middle East and into Europe, in a desperate attempt to escape a jihadist war.

It was the year that almost 200 nations signed a landmark agreement to address climate change, and it was the year that another once-in-100-year flood lashed northern England for the second time in less than 10 years.

It was the year that the concept of "the singularity" - when human computing is overtaken by machines - became a distinct possibility.

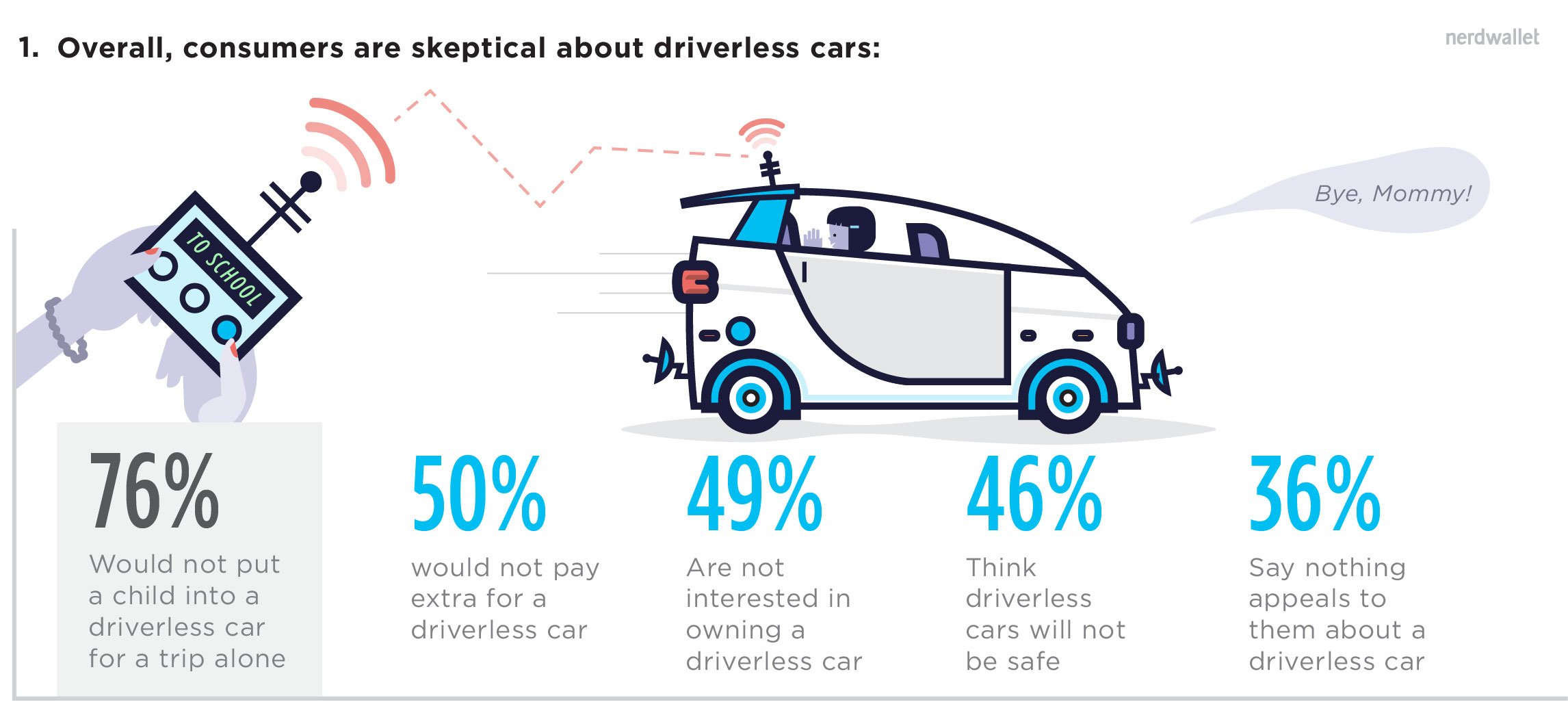

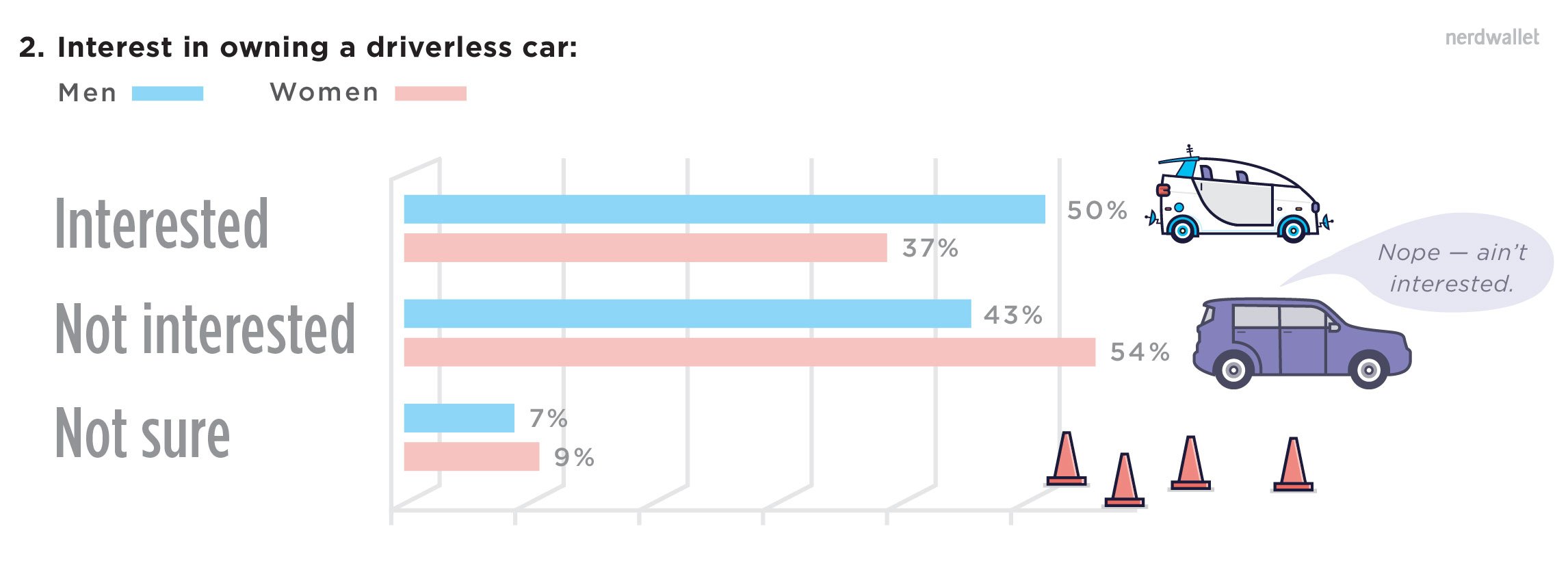

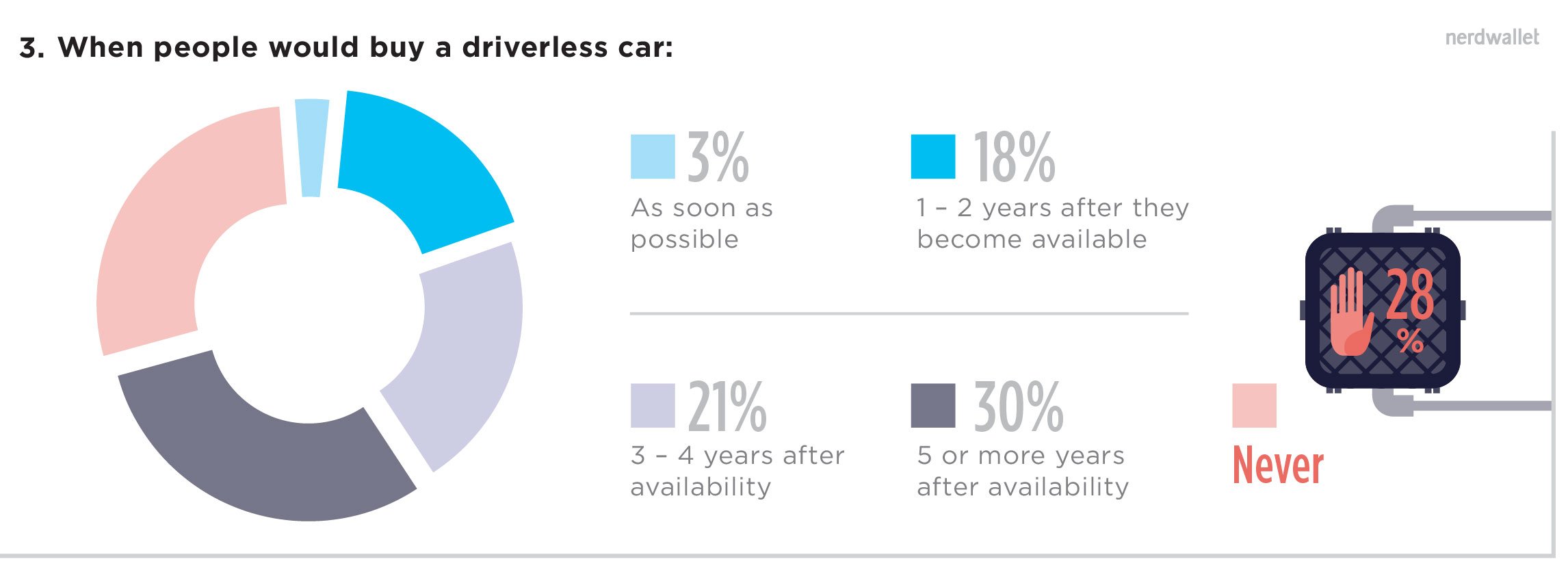

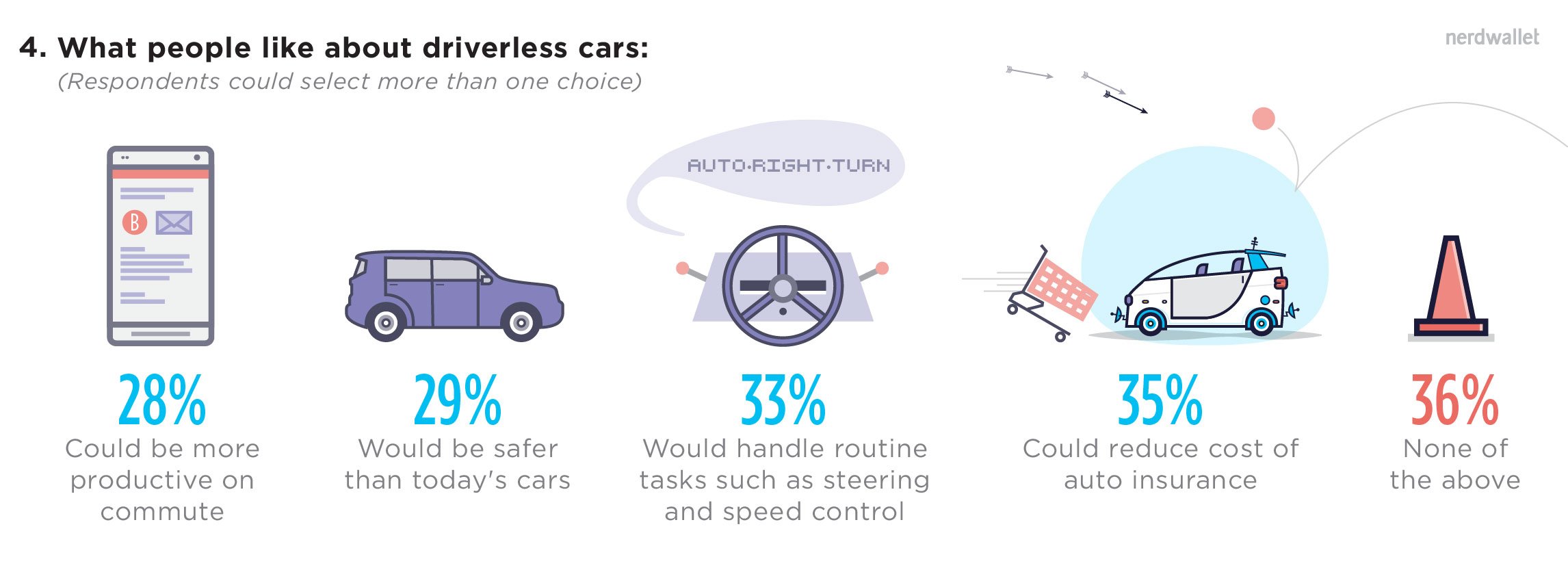

It was also a year when driverless cars, packages delivered by drone and 3D printing became tangible realities.

Here in Bermuda, 2015 was the year that signaled the demise of a brand name close to my heart - that would be ACE - as M&A fever reshaped the island's market landscape. It was also the year that the Bermuda Monetary Authority pulled off a coup - seven years in the making - by getting the European Commission to grant us Solvency II equivalence.

2015 was the year when Millennials - the generation born between the late '80s and the turn of this century - became the largest demographic ever. Think about it. More than half the world is now under the age of 30.

And it was the year when we truly began to exit a world driven by an analog mindset and woke up to the fact that we're living in a digital age. Labels like digital immigrants and digital natives were used to describe two of the four generations now making up our labor force.

I was invited to speak at a number of different venues this year, and, at each, I tried to describe this sense of being between two worlds.

I'd like to share some of the highlights with you, as I think these issues are going to be key to transforming our industry.

The first speech I gave this year was called "Risk in 140 Characters."

I was speaking to a group of Millennials in London, and I used Twitter as an example of stripping out inefficiencies to get to the core of a business model. I challenged them to figure out how we can leverage technology to make our industry more efficient.

I also challenged them to spread the word about the industry to their peers. Millennials don’t think much of insurance as a career. With 400,000 positions opening up in five years in the U.S., this lack of interest is creating a talent crisis.

The next speech was "Can We Disrupt Ourselves?"

I spoke to the International Insurance Society in New York a few weeks after I spoke to the Millennials in London, and described some of the game-changing forces our industry is facing - driven by disruptive technology.

I challenged this group - who represent executive management - to figure out how to attract a new generation to our industry, AND to figure out how to work with them. The solution to our disruption will come from the digital natives among us.

Then there was "Where Are the Women? One Year Later."

In 2014, I gave a speech called "Where Are the Women?" I asked why there aren't more women in the C-suites and boardrooms of the insurance industry.

This year, I looked at whether much has changed in a year - the answer is no - and what might be done.

The short answer is that people like me - the white males who dominate our industry - need to make gender parity and diversity a priority, and mean it.

A speech I gave to St. John's University's School of Risk Management was called "The Canary in the Coal Mine."

St. John's organized a day-long conference on issues facing the industry. I talked about M&A, alternative capital and the changing roles of brokers, cedants and reinsurers.

I also addressed the talent crisis, making the point that Millennials are the canaries in the coal mine.

If we don't pay attention to what they're telling us about our workplaces and work policies - and this includes our attitude toward diversity and inclusion - they're going to continue to snub our industry. And we can't afford to let that happen. Not only are they our future workforce, they're our current and future customers.

An address to 400 top producers of a brokerage firm was called "Do You Know How to Think Like a Unicorn?"

In Silicon Valley, companies backed by a $1 billion or more in capital are called unicorns, and those backed by more than $10 billion are called "decacorns." There are more companies with this level of capitalization now than at any other time.

And remember, most of these are tech start-ups, many of which are behind the disruption that's transforming our world.

I told the brokers that, in the digital world, they need to know their clients' business, and their clients' risks, better than the CEO does.

There's currency in knowing how to interpret data, and brokers have a great opportunity to develop specialized skills that they can monetize.

That's where the real value-add is.

According to a recent study by IBM, C-suite executives around the world are kept awake at night worrying about being ambushed by so-called digital invaders.

More than 5,000 executives participated in the IBM study. More than half of them told researchers that, above all else, they fear being "Uberized" - blindsided by a competitor outside their industry wielding disruptive technology.

While loss activity, interest rates and pressure on terms and conditions will always affect underwriting and financial performance, it's now a given that technology and talent will determine who will succeed and who will fail.

So, I asked the brokers: do you know how to think like a unicorn?

I was told later that this firm is now describing itself as a technology company whose product is insurance - so I guess they took my suggestions to heart.

So this year, I focused on five main themes:

- We still have rampant inefficiency in the way much of our business is conducted.

- We're threatened by technological disruption.

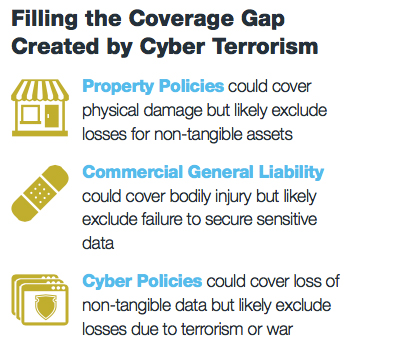

- We have unprecedented risks for which there are no actuarial data.

- The roles we play are being reinvented in real time.

- And we have a looming talent crisis.

Not a pretty picture, and not for the faint of heart.

But what scope for innovation!

I really do believe this is one of the most exciting times to be working in this industry in the 40 years since I joined it.

We enter 2016 with the hope that terms and conditions will improve, and the expectation that industry consolidation will continue.

[The recent increase] in interest rates could mean that our capital may take a hit, but we're likely to earn greater investment income over time, leading to increased revenue.

But these are the traditional hallmarks of a market cycle. This is the easy stuff.

There's nothing easy or traditional about what's facing our industry right now. Those of us who cling to the old way of doing business aren't going to make it.

It's the manner in which we navigate from the analog to the digital - how we move between two worlds - that will set our future course. This is going to take bold, courageous moves, some leaps of faith and a willingness to fail as often as we succeed.

I think it's telling that [in November] about 200 industry representatives and entrepreneurs gathered in Silicon Valley to figure out how to change the traditional insurance model.

They felt we need to flip the value proposition from protection to prevention, using data analytics to define the characteristics of a risk and identify how to avoid it.

A report on this conference described it this way:

"One of the biggest challenges for successful executive teams is to reframe a company's purpose away from its past greatness, and toward a different future."

We've been an industry where past is prologue. But for many of the risks we're facing, there is no past.

It really shouldn't matter. We're awash in data, but data pure and simple isn't the point.

We need to harness data to predict the future - in other words, adopt the prevention mindset.

The issue isn't simply gathering massive quantities of data. We need to take the data we have and know how to ask the right questions, and refine the right algorithms, to get the analysis we need to provide our products quickly and efficiently to a world doing business on smart phones.

To create the best risk solutions, we need to redefine the relationships we have with each other and build new organizational ecosystems. This is no time for staying in our traditional comfort zone.

And as an industry whose purpose is to secure the future, we have a collective obligation to address the massive protection gap between the developed and emerging economies.

In 2014, there were an estimated $1.7 trillion in losses. $1.3 trillion of that number was uninsured.

With collaborative undertakings like Blue Marble, the microinsurance consortium that was launched this year, we can begin to close this gap. This not only helps prevent disaster for the underserved, it helps build a sustainable planet.

I know we can figure out how to re-create our workplaces, finding ways to meld the experience and traditional perspective of Baby Boomers like me with the open, diverse, purpose-driven focus of Millennials.

This might be one of our greatest challenges, because it aims straight at the heart of our industry's old-school DNA.

By the way, I like that Millennials are purpose-driven - because what industry can more rightfully lay claim to purpose than insurance?

As I said in one of my earlier speeches, insurance should be catnip to a Millennial.

Several of us are banking on that being true by supporting an awareness program to let the younger generation know that this is a great career choice.

I've been joined by Marsh's Dan Glaser and Lloyd's Inga Beale in signing a letter urging our fellow CEOs to put their companies' weight behind this initiative.

The first phase of this plan is an Insurance Careers Month that will be launched in February 2016. This is primarily a U.S.-based project because that's where the urgent need is, but other markets will be participating, too. We were aiming to enlist the support of at least 200 carriers, brokers, agents and industry partners - and at last count we had almost 260 signed up. The response has been great.

So, in closing:

It HAS been quite a year.

The way we live and work is changing faster than I think any of us thought possible. We have some amazing challenges and opportunities ahead of us - here in Bermuda, and in the countries where many of us do business.

I'm excited about where we're going and how we'll get there, and I hope you are, too.

I believe it's the best of times.

In the meantime, I hope you all have a great morning of provocative thought and discussion, and I wish you a safe, happy and healthy holiday season.