This article was written with Adrian Jones, a #traditionalindustry guy and insurtech investor who writes in his personal capacity. The authors’ opinions are solely their own, and only public data was used to create this article.

***

“

All the insurance players will be insurtech,” as Matteo titled his recent book, but some insurtechs have chosen to be insurers. Real insurers. Which means they file detailed financial statements. These obscure but public regulatory filings are a rare glimpse into the closely guarded workings of startups.

Full-year 2017 filings for U.S.-based insurers were released earlier this month. Here’s what we found:

- Underwriting results have been poor

- It costs $15 million a year to run a startup insurtech carrier

- Customer acquisition costs and back-office expenses (so far) matter more than efficiencies from digitization and legacy systems

- Reinsurers are supporting insurtech by losing money, too

- In recent history, the startup insurers that have won were active in markets not targeted by incumbents

We explain and show data for each of these points in this article.

Context and Sources

The most notable recent independent U.S. property/casualty insurtech startups that operated throughout 2017 as fully licensed insurers are Lemonade, Metromile and Root.

Out of hundreds of U.S. insurtech startups, only a few have taken the hard route of being a fully licensed insurer. The lack of interest in becoming a regulated insurer is evidence against disruption evangelists who say that insurers are going to disappear or be killed by GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon).

Despite the lack of interest, being a fully licensed insurer may prove to be a more durable business model than the alternatives like being an agency or otherwise depending on incumbents, and the three carrier startups that we analyze all have strong teams with powerful investors. Adrian has previously argued that being a fully licensed insurer may actually be the best long-term strategy – See:

Six Questionable Things Said About Insurtech.

The filings we reviewed are called “statutory statements.” and only insurers file them, not agencies, brokers or service providers. Statutory statements provide many of the traditional KPIs of insurance companies. Startups may use additional internal measures as they scale their company. Statutory statements typically do not include the financials of an insurer’s holding company or affiliated agencies, and companies have some flexibility in how they record certain numbers. But for all their limitations, statutory figures have the benefit of being time-tested, mostly standard across insurers and measuring critical indicators like loss ratio and net income.

See also: Innovation: ‘Where Do We Start?’

Though the public can access statutory statements, it’s not always easy.

Some insurers post them online, even private insurers. This is an area for improvement by both the #traditionalindustry and the startups that tell tales of “transparency” but don’t upload their statutory statement.

The statistics

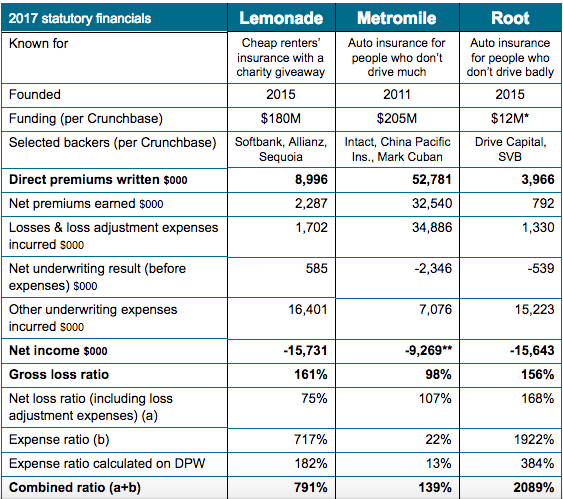

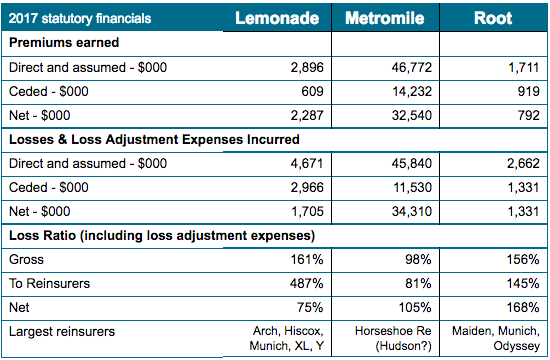

Here are the key stats on three companies – from top line to bottom line:

[caption id="attachment_30864" align="alignnone" width="563"]

*The company has gross paid-in surplus of over $31 million so this figure is probably low. **Excludes a write-in for “revenue from parent for administrative costs,” possibly a way of topping up the company’s surplus[/caption]

A combined ratio greater than 100% usually means a loss. Combined ratio doesn’t include returns from investing insurance reserves, but the days of double-digit bond yields are long gone. In a low-rate environment, investment income can’t offset poor technical results. The ratios are typically calculated on net earned premiums, but we also show a row where the expense ratio denominator is total direct premiums written, which may be more appropriate for growing books.

Observations:

- Lemonade

- Considering the statutory top line before reinsurance of $8,996,000 of gross premium written, it’s unclear how Lemonade calculated that “our total sales for 2017 topped $10 million.” The premiums reported by Lemonade may already have deducted the 20% fee paid to the affiliated agency – the parent company’s only source of income due to the giveaway model. (This would also explain why there is no commission and brokerage expense showing.)

- Lemonade claims to have insured “over 100,000 homes.” If we assume that this figure includes rented apartments, then it implies premium written per policy of $90, or $7.50/month, if premium written is based on an annual policy.

- Lemonade’s giveaway does not appear to be separately disclosed. Nonetheless, one of the brilliant aspects of the business model is the fact that even with a 791% combined ratio, Lemonade still has at least one or two pools doing well and thus enabling the PR of a giveback.

- Metromile

- As the oldest startup in this group, Metromile has by far the highest premium, but the loss ratio is still nearly 100%. The expense ratio appears to have scaled down to a reasonable number, but the company puts $7 million of expense into “loss adjustment expense,” which may flatter the expense ratio.

- Root

- As with Lemonade, the loss ratio around 160% is cause for concern – is this a few volatile claims (bad luck) or a problem with pricing? Time will tell.

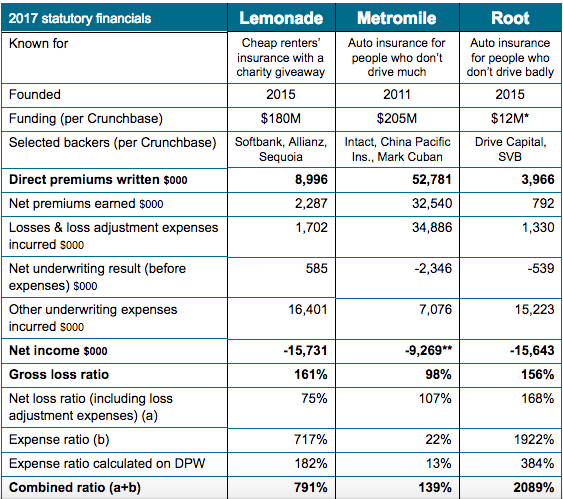

A few other notable companies are worth a mention:

- Berkshire Hathaway Direct Insurance sells online via biBERK.com but isn’t a venture-backed startup. They wrote $6.4 million in premium last year, their second year of operations, most of it workers' compensation. Their loss ratio gross of reinsurance was 124%.

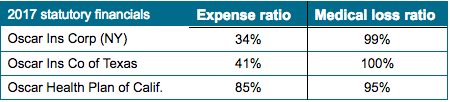

- Oscar is a startup brought to you by Jared Kushner and others who have plowed in $728 million already, with more funds being raised currently. Oscar shows no signs of profitability in its three main states:

1. Underwriting results have been poor

1. Underwriting results have been poor

All three companies have a gross loss ratio of near 100% or higher. (For reference, the industry average in 2016 was 72%). That means they have paid $1 as claims for each $1 earned from policyholders in the last 12 months.

An insurance startup has to prove two critical things:

- Does the underwriting model work?

- Does the distribution model work?

We’ve been in debates over which is more important, and we always start with underwriting, because it takes no special talent to distribute a product that has been poorly underwritten (i.e. selling below cost). Underwriting quality/discipline is one of the “

golden rules” of the insurance sector. Disrupt it at your investors’ peril.

Underwriting returns have generally been poor, in some cases awful (double the industry average counts as awful in our book). Poor results are to be expected at first, even for the first several years. A single big loss can foul a year’s results in a small book. It can be hard to tell if that single loss is an anomaly or a failure in the model. Building an underwriting model is like playing whack-a-mole with a year’s time lag. Sometimes it’s difficult or impossible to address

even widely known underwriting issues.

2. It costs $15 million a year to run a startup insurtech carrier

All three companies incurred right about $15 million in run-rate expenses last year, of which $5 million to $6 million is headcount expense. It may be possible to keep the overall expense total closer to $10 million if one is especially lean, but the cost of operating in a regulated environment and building a book quickly mount.

Some startups have organized as a managing general agency instead of a carrier. Thus they pay a “front” a fee of around 5% to produce their policies. However, even MGAs are state-licensed entities that are subject to most of the same regulation as carriers, so the expense saving of being an MGA is only a true savings at small volumes.

The upshot: The capital raises of around $20 million to $30 million that we have recently heard about may only be good for around two years of operating expense, before any net underwriting losses.

See also: Insurtech Is Ignoring 2/3 of Opportunity

Scale matters in insurance and venture capital, but it’s a double-edged sword in insurance. Scaling too quickly without underwriting excellence magnifies underwriting losses, but staying too small leaves the book volatile and the expense ratio high. Some startups have been active for several years and have not yet scaled, or even saw a reduction of premiums in the last year, but this may be better than scaling without sustainable underwriting results. Future financial statements will tell if any of the new players will gain a sustainable market share in a major business line in the U.S., or at least in a niche.

3. Customer acquisition costs and back-office expenses (so far) matter more than efficiencies from digitization and legacy systems.

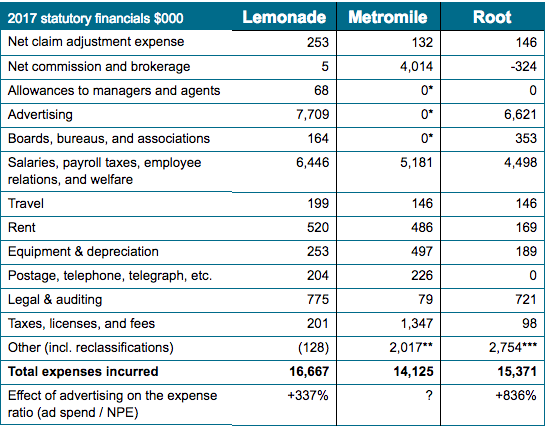

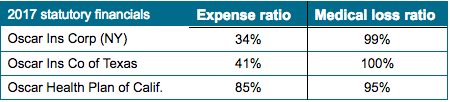

Insurance investors need to understand back-office expenses and distribution expenses, both of which are typically fixed costs for startups distributing directly to consumers. Here’s a look at what the three property/casualty insurance startups are spending money on. Beware that holding company expenses and affiliated agencies may or may not be reflected in the figures below, depending on the intercompany arrangements in place.

[caption id="attachment_30866" align="alignnone" width="548"]

*Likely included in commission and brokerage expense, which is net of $2.1 million ceded to reinsurers **Largest write-in item is “other professional services” at $891,000. ***Includes $1,958 of unpaid current year expenses and write-ins like “other technology” and “contractors”[/caption]

Observations:

- Lemonade:

- This startup is spending almost $1 in advertising for every $1 of premium they wrote ($7.7 million of advertising for $9 million of premium written). Again, if we assume Lemonade has insured 100,000 homes and apartments, then the customer acquisition cost (CAC) assuming only advertising expense is around $77. This is probably a measure that encourages the company’s backers, because the CAC of a renewal policy written directly is minimal, and the industry-average churn rate is single digits in U.S.

- The regulatory and overhead costs are considerable – notice lines like legal and auditing; taxes, licenses and fees; and some of the salary expense.

- The volumes have to continue to grow exponentially for some years to get the cost base (also net advertising) lower than the 20% of the premium required to make a profit for the parent company (for reference, the market average expense ratio was 28%). Recall that Lemonade’s parent or affiliates take a 20% flat fee up front for their profits and expenses and gives to charity anything left after paying claims and reinsurance.

- Metromile:

- Has the highest tax expense, perhaps because it is selling the most, with many states charging premium tax as a percentage of the policy value.

- Their “legal and auditing” expense is probably much higher but is put into “other.”

- Note the absence of advertising expense but large commission and brokerage expense, partially ceded to reinsurers. Accounting treatments, as ever, can vary by company.

- Root

- The company’s small volume makes it difficult to run the same absolute expenses as Lemonade and Metromile, but it might not be wise to grow a book running a loss ratio of more than 150%.

- Has no telegraph expense (woo-hoo!).

- Unclear why the company has almost $2 million of unpaid expense.

Advertising expense vs. pricing. Old-fashioned insurance agents are a variable cost that scales up with the business – the agent absorbs fixed advertising, occupancy and salary costs in exchange for a variable commission. But in the direct distribution models favored by many startups, variable costs and agents’ costs become fixed costs borne by the startup. (True, some can be kept variable, as we discuss below.) Fixed costs need to be amortized over more premium volume, which requires yet more fixed costs (e.g. advertising) to solve.

Insurtech carriers from the dot.com era like eSurance and Trupanion are still investing heavily in advertising and producing losses or barely breaking even. They would probably argue that they could eliminate much of their expense and “harvest” an attractive book of business for years to come – which may be true. The U.S. churn rate in personal auto and home insurance can be as low as single digits, far lower than many Western countries. Because customer-retention cost is much lower than customer-acquisition cost, loyalty is absolutely critical to non-life insurers, particularly in a direct distribution model. (Bain & Co. – both of us are alumni of this consulting firm -- has done excellent

work on loyalty in insurance.)

It is tempting to acquire insurance customers by underpricing and later transforming them into profitable customers. A loss ratio of more than 100% implies a pricing problem, not a problem with the underwriting model. Insurers with a customer base that came for cheap insurance and expects it to continue will find their market vanishes when they begin repricing to bring loss ratios to acceptable levels, destroying any value from customer loyalty and forcing a pivot to a new value proposition. In some cases, it may be necessary to double prices before underwriting price adequacy can be achieved, even ignoring expenses. (Most U.S. state regulators also have broad powers to disapprove, block or roll back rate increases – for more on the maze of state regulation, see

this study from the R Street Institute.)

The API approach – a B2B2C model based on distributing the product through the digital fronts of third parties – has become “the new black” to transform fixed acquisition costs in success fees linked to the volumes. This model shows promise, provided that distribution partners do not extract too much value from the competitive insurance market.

The point for founders and investors today is to be prepared mentally and financially for a long road to profitability with tens of millions sunk before it becomes apparent whether the underwriting works and whether the relationship between CAC/distribution, fixed expenses and customer loyalty can produce a sustainable and profitable business.

4. Reinsurers are supporting insurtech by losing money, too

Some members of the #traditionalindustry have strongly supported the development of insurtech through investment in equity, providing regulatory capital, providing risk capacity and sharing technical expertise. Startup insurers typically are reliant on reinsurance as a form of capital because (1) it can be cheaper than venture capital, (2) startups typically need reinsurance to hold their rating and (3) the strong backing of a highly rated reinsurer shows validation of the company’s business model, just like the backing of the best VCs provides.

The carrier model has real advantages concerning reinsurance: reinsurance is easier to arrange and more flexible than an MGA relationship. Many successful agencies find that their economics would be better if they were able to retain some of the risk they produce instead of writing on behalf of a licensed carrier and ceding that carrier all but a commission.

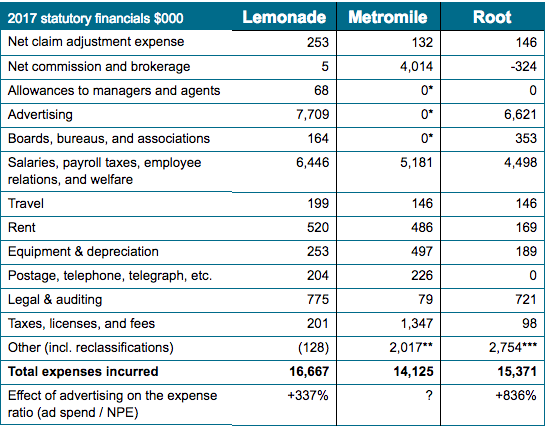

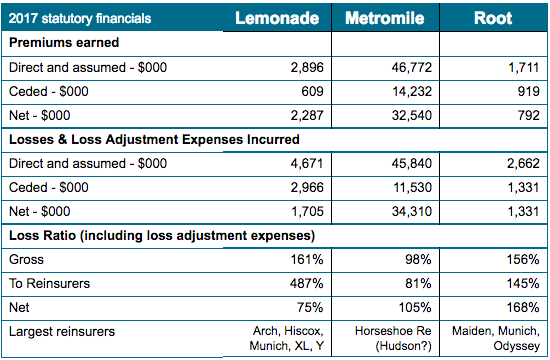

Here is a look at results disaggregated for reinsurance:

[caption id="attachment_30867" align="alignnone" width="550"]

(Source: Schedule P; subject to minor variations compared to prior tables)[/caption]

Observations:

- Lemonade seems to have a great reinsurance scheme, but they have to hope that reinsurers continue to take $5 in losses for every $1 in premium ceded to them. The amounts ceded are small, and Lemonade has a big panel of reinsurers.

- Metromile and Root do not appear to get much loss ratio benefit from their reinsurance.

It is a great experience for a giant reinsurer to work with a small and innovative startup. The expected losses in dollar terms are negligible if compared with the value of the lessons learned, the culture created and the halo the reinsurer may partially claim. Startups need to find reinsurers that are both flexible and prepared for losses, potentially for several years. But startups cannot count on reinsurers to take losses forever.

5. In recent history, the startup insurers that have won were active in markets not targeted by incumbents.

Since 2000, at least 34 property/casualty insurers were formed in the U.S. without the aid of a powerful parent and earned more than $10 million in premium in 2016.

Of these 34 startup insurers:

- 21 specialized in high-volatility catastrophic risk like hurricanes or earthquakes. Incumbent carriers have largely stopped or greatly limited their new business in certain catastrophe-exposed regions, sometimes because they felt that regulators or competitors (often government-run pools) did not allow them to charge adequate premiums.

- Nine were motor insurers, mostly non-standard motor. Non-standard means bad drivers, exotic cars or other risk factors that “standard” carriers avoid.

- Two don’t have a rating.

- Two remain: Trupanion (a pet insurer) and ReliaMax (which insurers student loans).

Adrian readily acknowledges that some carriers aren’t picked up by his screen, such as financial lines companies like Essent. Essent is a Bermuda-based mortgage re/insurer that wrote $570 million of premium at a 33% combined ratio in 2017 after a standing start in 2008 – which might be the most successful U.S.-market insurance startup in the last decade. Other startups were sold along the way, were sponsored by a powerful parent or purchased an older “shell” and inverted into it.

The point is that successful insurers have rarely won by attacking strong incumbents in their core markets. They have won by figuring out ways to write difficult risks better than incumbents, have created markets (like pet insurance) or have entered seriously dislocated markets with good timing (like writing mortgage insurance in 2009).

This leads to several questions:

- Are urban millennials actually a new market that is being ignored by incumbents?

- Are direct and B2B2C distribution really new markets that incumbents cannot penetrate? Can “platformification” be profitable over the long term?

- How quickly can new/digital systems show cost and pricing benefits over legacy systems that incumbents are retooling aggressively today? How long before the new systems become a legacy for the newcomer that created them?

- Are new underwriting and claims techniques like the use of big data sufficiently disruptive to allow entry to tightly guarded markets?

There are early signs that all of these questions will be answered favorably for at least a couple of startups but not without some bumps along the way.

See also: Insurance Coverage Porn

Previous waves of technological changes have allowed new competitors to rise to prominence – think of the big multi-liners that dominated the skyline of Hartford CT with mainframe technology in the ‘50s and ‘60s, the specialists like WR Berkley built on personal computers in the ‘70s and ‘80s and the Bermuda CAT specialists of the ‘90s and ‘00s. Will the next wave of technology-driven insurers include the ones today putting up 150%-plus loss ratios? Perhaps.

***

Conclusion

Technology changes a lot, but it doesn’t change fundamental facts that make insurance hard. As we said at the start, we admire and support the companies that choose to become fully licensed insurers. They have taken the harder path to market but may be more durable in the long term. We think commentators should be very careful before criticizing startup insurers for not having great performance on the loss ratio and expense ratio in the first few years. We also think companies need to be careful about overselling the awesomeness of their business model too early.

To use

Matteo’s 4Ps framework to judge any insurtech initiative – from startups or incumbents, we have yet to know whether/how new challengers can leverage technology to outperform incumbents on technical profitability, productivity, proximity with the clients and persistency of the book of business. Whoever is capable of doing this will survive and may be the next big winner in insurance. Insurtech startup carriers, their investors and their reinsurers need to be prepared for a long and expensive startup phase. Insurance is a get-rich-slowly business, but it is also a durable business that rewards patience, wise risk-taking, data analysis and operational excellence.

And for the futurists, disruption evangelists, black swan hunters and anyone who just learned more about insurance than you ever wanted to know, we hope these dispatches from insurtech Survival Island have been informative for examining startup financials in insurance or other markets where you operate.

Please follow Adrian and Matteo on LinkedIn for future posts.

The three highest-scoring departments were Underwriting (with 70% of respondents naming it), Pricing (55%) and Marketing (54%). Other areas that warrant mention were Actuarial (51%) and Distribution (36%). We noted in our earlier post on Marketing & Customer-Centricity that the roots of today’s consumer-led disruption are in the rise and ease-of-use of new distribution channels – so insurers that leave Distribution outside of their product discussions do so at their peril!

See also: Next for Insurtech: Product Diversity

Which insurance lines are driving the greatest degree of product innovation?

In addition to seeing product as department-driven, we also investigated the extent to which it is line-driven. The chart below shows Auto (voted by 56% of respondents), Home (45%) and Health (41%) to be the three lines experiencing the most product innovation (according to carriers taking our survey). This is corroborated anecdotally by the sheer number of in-market IoT products we see across these fields, from in-car telematics through to smart-home controllers and connected-health armbands.

Life and Commercial are relative laggards in this regard, although we do believe there is ample opportunity in both these areas. This may follow the same pattern we identified with IoT (itself an abundant source of product innovation), where we saw platform implementation in Commercial currently trailing but quickly drawing level with other lines (see our earlier post on IoT). Regional trends for this question warrant some high-level comment:

The three highest-scoring departments were Underwriting (with 70% of respondents naming it), Pricing (55%) and Marketing (54%). Other areas that warrant mention were Actuarial (51%) and Distribution (36%). We noted in our earlier post on Marketing & Customer-Centricity that the roots of today’s consumer-led disruption are in the rise and ease-of-use of new distribution channels – so insurers that leave Distribution outside of their product discussions do so at their peril!

See also: Next for Insurtech: Product Diversity

Which insurance lines are driving the greatest degree of product innovation?

In addition to seeing product as department-driven, we also investigated the extent to which it is line-driven. The chart below shows Auto (voted by 56% of respondents), Home (45%) and Health (41%) to be the three lines experiencing the most product innovation (according to carriers taking our survey). This is corroborated anecdotally by the sheer number of in-market IoT products we see across these fields, from in-car telematics through to smart-home controllers and connected-health armbands.

Life and Commercial are relative laggards in this regard, although we do believe there is ample opportunity in both these areas. This may follow the same pattern we identified with IoT (itself an abundant source of product innovation), where we saw platform implementation in Commercial currently trailing but quickly drawing level with other lines (see our earlier post on IoT). Regional trends for this question warrant some high-level comment:

Human hand pointing at touchscreen in working environment at meeting[/caption]

Key trends in the development of products

It’s clear from this section so far that product development is a strategic priority for a diverse spread of departments and lines. But how are insurers actually going about product development on the ground? Let us now present our trends on a number of product approaches that we identified among our carrier respondents: product diversification, Usage-Based Insurance (UBI) and product bundling/upselling.

Human hand pointing at touchscreen in working environment at meeting[/caption]

Key trends in the development of products

It’s clear from this section so far that product development is a strategic priority for a diverse spread of departments and lines. But how are insurers actually going about product development on the ground? Let us now present our trends on a number of product approaches that we identified among our carrier respondents: product diversification, Usage-Based Insurance (UBI) and product bundling/upselling.