Technological disruption: artificial intelligence, blockchain, telematics, genomics, the Internet of Things.

Economic disruption: imagine: AirBnB is now the #1 hotel company, Uber is the #1 taxi company, big stores and shopping malls are fighting for their lives. Sears, the Amazon of the 20th century, recently declared bankruptcy, and many traditional bricks-and-morter retailers are threatened.

Social disruption: some parts of the world are aging rapidly, with attendant retirement savings and healthcare challenges, while other parts, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, have more young people than jobs; people want to be able to use things without necessarily owning them; concepts of work are changing; income equality and gender equality are major issues.

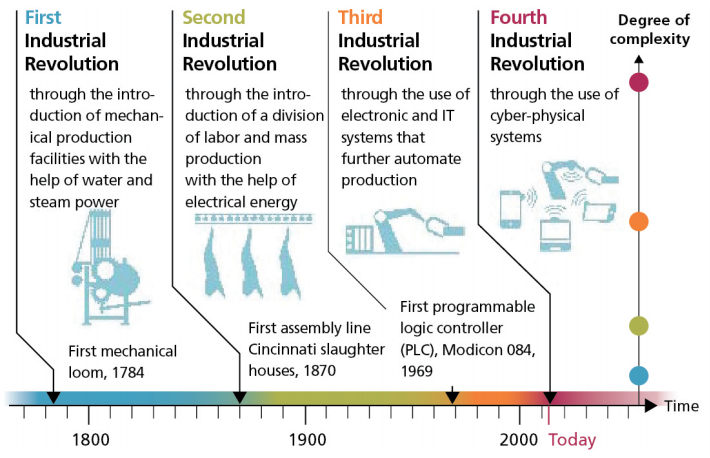

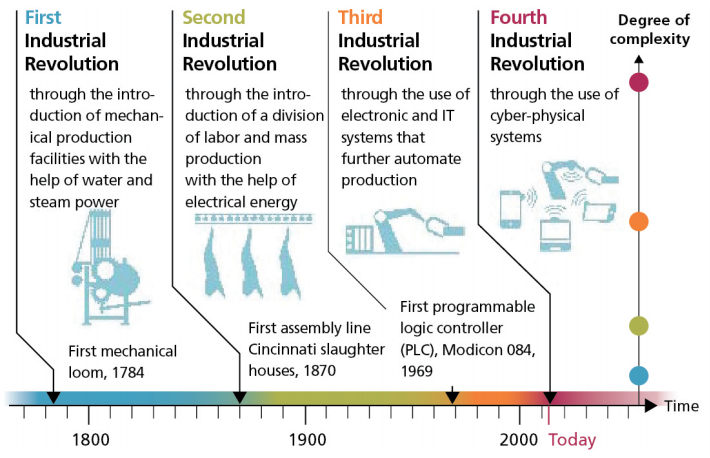

While the concept of a Fourth Industrial Revolution is now widely discussed, I would like to describe the Fourth Insurance Revolution as I see it. Like the eras of the four industrial revolutions, there have been three previous periods in insurance industry history that are somewhat similar to the evolution of the industrial world.

The first era, which I call Insurance 1.0, began logically enough in the parts of the world that were the cradles of civilization, the Middle East and Asia.

See also: Industry 4.0: What It Means for Insurance

As far back as the second and third millennia BC, traveling Chinese merchants practiced an early form of risk management by distributing their wares among numerous ships and different trade routes, to minimize losses along the way. In Babylonia, merchants receiving a loan to ship goods paid the lender an additional fee that would cancel the loan if the goods were somehow lost – credit insurance. This form of coverage is even memorialized in the Code of Hammurabi. The Greeks and Romans introduced the origins of life and health insurance when they created guilds called benevolent societies, to pay family members for funeral expenses of deceased members. These are our industry’s beginnings.

Insurance 2.0 as I see it was the introduction of the first actual insurance contracts. These were developed in Genoa, Italy, in the 14th century and related to marine insurance for goods in transit. This was a formalization of the earlier concepts employed in the Insurance 1.0 period.

Our industry matured greatly in the 17th century, into what I deem Insurance 3.0, a major leap forward.

Much of the accelerated formalization of insurance was stimulated by the Great Fire of London in 1666. This enormous conflagration destroyed nearly 70,000 of the city’s 80,000 residences, and gave rise to urgent risk management and insurance planning. Property and fire insurance as we know it was launched by Nicholas Barbon in London in 1681. Around the same time, French mathematicians Blaise Pascal and Henri de Fermat conducted loss probability studies that resulted in the first actuarial tables. Insurance became an empirically based enterprise, and became widely understood to be a prudent expenditure for businesses and families.

With that brief history of the evolution of our industry, let’s now move on to insurance in the 21st century: Insurance 4.0

In my view, most of the change in the industry since Insurance 3.0 up until the present has been incremental. Broader product lines, more distribution channels and, recently, the first elements of digitization. But what’s happening now is fundamentally different. The basic function and processes of insurance are being disrupted at an accelerating pace.

So let me now present some of the issues and implications of change in the industry, what Insurance 4.0 looks like. I’ll start by making some comments on the insurance industry of today.

Of course much of the rapid change taking place now and defining Insurance 4.0 is related to technology. The insurance industry’s raw material is data. Data not only to make underwriting and loss reserving judgments, but increasingly to manage virtually every business process in the insurance value chain. Data is valuable. But how can insurers successfully plan and manage data when, as Science Daily magazine tells us, 90% of all the data in the world has been generated in the last two years?! How do we use this avalanche of data to make sound business decisions? More data does not inevitably lead to better decisions.

One promising set of tools: Artificial intelligence and machine learning, which represent a quantum leap from the predictive modeling insurers have been using over the past decade.

Moving rapidly from applications in high-frequency, low-severity lines like auto and home insurance, AI capabilities are now employed in more complex commercial lines, and already show evidence of having real underwriting and loss reserving value.

Skeptical about whether this can work in complex cases? Let me give you an AI example. A few years ago, a computer beat the world chess champion. Well, some said, that’s fine, but it will be a long time before a computer can beat a top Go player. As many of you know, Go is a complex Asian game played on a 19-by-19 grid, with more possible configurations than the number of atoms in the known universe. Google’s Deep Mind Lab computer input all the Go games ever recorded, over a 1,000-plus year span. After playing 4.9 million games against itself in a three-day period to learn, the computer immediately beat the world’s best Go player in a live game.

What’s more thought-provoking, though, is what happened next. Putting aside the input of historical game results, Google just uploaded the basic rules of the game – no experience data. This new program, AlphaGoZero, became expert simply from learning first principles alone, without any human knowledge or experience input. Does anyone still think sophisticated underwriting or loss reserving is beyond the capability of modern computers? I don’t.

Entrepreneurs have expanded the way technology can influence the insurance value chain to create an ecosystem we call insurtech. Leveraging off fintech’s huge impact on the banking and payments world, insurtech companies, which now number more than 100,000, are innovating in every insurance company department. Investments in them have grown by leaps and bounds. Insurtech attracted about $140 million in funding in 2011, $275 million in 2013, $2.7 billion by 2015 and more than $4 billion last year.

Insurtech products and services address product development, marketing, pricing, claims and distribution, especially reducing policy acquisition costs, and have been much more focused on nonlife insurance (especially personal lines) than life and health insurance to date. Up until now, insurtech ventures have tended not to displace the incumbent insurers, but have been invested in or acquired by them to enhance their existing operations.

Much of the industry’s current expanded use of technology, including insurtech, is focused on customer interface and the customer experience. It has always been said that an industry can’t disrupt itself; that disruption always comes from the outside. Not surprisingly, then, insurance policyholders and potential customers have had their expectations of customer experience elevated by their interaction with other product and service providers. No longer do they measure their satisfaction against other insurance companies. They want the kind of experience they get from Apple, Alibaba, Amazon, Starbucks and the like. They want mobile, 24/7, personalized service. Most insurers today are simply not capable of delivering this. They lack both the innovation mindsets and the IT budgets to deliver a 21st century insurance customer experience, and they will lose share of market to those companies that do.

Another element of change in today’s insurance business is the emergence of public/private partnerships. More sovereign and sub-sovereign governments have come to realize that they are effectively the insurers of last resort when catastrophes strike.

Efforts are accelerating to narrow the protection gap between total economic losses and the portion covered by insurance.

Because the governments often end up paying directly or indirectly for disasters, and their citizens feel their brunt in terms of higher taxes or reduced services, governments now increasingly seek to partner with insurers. This is a positive development for the industry, one that presents both an enormous growth opportunity and a benefit to society.

Recent years have seen the launch of the African Risk Capacity, the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Fund and the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Insurance Company. All are regional public/private partnerships, and all are enabled by technology-driven parametric triggers. Others are in the works, facilities designed to address a range of perils including flood pools, terrorism pools and the like, best managed by governments and industry working together.

The “lower interest rates for longer” world we live in presents major challenges for investing the assets that support our policy liabilities. Insurers can no longer simply commit the bulk of their portfolios to investment grade corporate and government debt. Such a strategy just isn’t sufficient to pay claims and provide an adequate return on capital now.

Insurers and the asset managers who serve them have responded by changing their asset mix, to increase allocations to higher-return, not-much-higher-risk securities (let's hope). More equities. Structured products and bundles of loans. Private equity funds. And recently, infrastructure debt, in both developed and emerging markets.

Portfolio yields are rising, but only time will tell whether these new investment allocations provide an appropriate margin of safety in more turbulent market conditions. It’s really too soon to tell if the industry’s investments have become riskier, or if insurers have simply better understood the true risks of 21st century investing.

A more subtle but truly profound change in Insurance 4.0 is the industry’s focus on talent. I’ve been in the insurance business more than 47 years, and I can say with complete confidence that insurers have never remotely spent as much time, money and thought on developing their future leadership as today. There has always been talk about this, but the action has never before matched the rhetoric.

With approximately 25% of the industry’s top management retiring in the next five years, as Baby Boomers retire in large numbers, the urgency of talent development has finally dawned on CEOs and even boards. Competing for top young talent isn’t easy. The lure of technology firms, entertainment, investment banking and other seemingly more exciting career paths is undeniable. But insurers have to try to attract at least some of the best, because our industry’s role in society is so critical, and the talent gap is large and growing.

For the first time in my career, CEOs bring up their programs for attracting, developing and retaining talent without me asking them first. More and more describe carefully thought-out programs that are so strategically important that they have high visibility with their boards. Believe me, this is a real change. These are the companies that will thrive over the long term.

All of these initiatives, in technology, in the customer experience, in public/private partnerships, in new investment approaches as well as in talent development, exemplify Insurance 4.0. Not just doing what we have always done, hoping to be somewhat better, but developing new tools to address new challenges, new opportunities and new competitors from within and without the industry.

This is because insurers are the financial first responders in this risky world. We rebuild communities and homes after disasters, we provide financial stability when families lose loved ones and we invest to build economies around the world, and in Insurance 4.0 we do it faster and better.

As numerous and daunting as the changes of today are for the insurance industry, there will be more and greater challenges in the industry of tomorrow.

The accelerating pace of change in our world not only demands new products, but presents entirely new forms of risk, as well. I referred earlier to the three generic kinds of disruption we are witnessing. Each of them carries new risk exposure the likes of which our industry has not dealt with before.

Technology disruption, for example, presents a host of new risks related to our connected world. Insurers are struggling to find their place as autonomous vehicles loom large in our future. What does this mean for the motor insurance business, the industry’s largest line of coverage? Will auto manufacturers simply bypass the insurance industry and go directly to the capital markets for their enormous coverage needs? Will commercial drones inspecting property damage claims improve workflow and reduce reliance on human error?

How will blockchain reduce expenses? The InsureWave project developed by EY, Maersk, Willis and GuardTime promises to slash marine insurance expense ratios by approximately 10 points! Other blockchain applications are in the works, and industry consortia like The Institutes’ Risk Block Alliance are finding new processes to save and make money every day now.

Finally, cyber risk represents the world’s first truly global peril, including a cascading potential due to our connectedness. Clearly, there is premium growth potential in cyber, but the early promoters of long-term-care insurance might remind us that revenue growth potential does not necessarily portend long-term profit. Current cyber combined ratios are running around 60%. True loss experience, though, will take years or decades to be fully understood.

Economic disruption also presents new challenges and opportunities for insurers going forward. Who will be the insureds of the future? How does a company insure Uber or AirBnB, let alone the people who use them and the facilities they work with? How does the collapse of traditional industry customers like retailers, coal companies and other industries that dominated the 20th century affect insurers? And by the way, is the industry prepared to cut 25% to 50% of its non-customer-facing jobs over the next decade as a “benefit” of AI and robotics? Some of the internal workforce can become part of the “hybrid system,” the human overlords who write and work alongside the smart systems to make their ultimate decisions, but not many.

Social disruption is also a source of new risks. For nonlife insurers, reputation risk and privacy risk have enormous potential exposures, and little existing loss data to make rates. It’s much too soon to tell if providing coverage for these exposures will be viable or not.

What are the insurance implications of the sharing economy, where more people want the ability to use things without owning them? Usage based insurance is gaining popularity, but also has the potential to significantly reduce premium volume. What about the “gig economy,” where many people hold several part-time jobs and no full-time job (meaning no benefits)?

And how will life and health insurers cope with a rapidly aging developed world? Retirement savings is a looming crisis. And even if we manage to avoid pandemics (consider: If the Spanish Flu of 1918 occurred today, it could kill 400 million people), what are the implications of a hotter and more polluted planet for healthcare? Will wearable devices driving the Internet of Things provide a cornucopia of information to enable better health outcomes?

See also: Insurance Service Rates Zero Stars

And what of the big issue: climate change? Both the World Economic Forum and Lloyd’s of London define climate change as a top socio-economic risk to our society. Climate risk is now considered a core strategic issue by governments, businesses, even the military. Certainly for the insurance industry, adaptation and mitigation, the need to make future provisions for inevitable damage, and send pricing signals to insureds of the true cost of risk, is a defining issue of our time.

In a broad way, Insurance 4.0 means the industry is becoming part of an ecosystem of connected and communicating sectors that are symbiotic, not as “B to B,” business to business, or “B to C,” business to consumer, but “E to E”: everything to everybody, where the information exchange benefits all participants, but is not equally understood by all parties. The information flow is asymmetrical. We can all agree that reducing risk in our world is a good thing for society, but, if risk is materially reduced, will the size and relevance of our industry then shrink?

A few words are also in order about the political capital the insurance industry possesses. I have written herein mostly about the risk management side of our business, and indeed it is the very reason we are in business. But even in a time of increasing public/private partnerships seeking to mitigate and remediate natural disasters, politicians and policy makers primarily ascribe our industry’s power and influence to our investment portfolios.

Globally, the industry has over $35 trillion of invested assets. Assets that are invested in companies’ domiciliary countries’ government bond markets and are critical to those countries.

Assets invested in their stock and corporate bond markets, as well. And now, insurers’ role, along with pension funds, as the only true long-term investors, means they are vital to infrastructure funding. Growth projects for the emerging world, and reconstruction financing for the developed world. This is what gets the attention of policymakers. And so this attribute is what we must nurture and promote to enhance our stature. Our most promising avenue to high esteem with policymakers is by securing their understanding of the vital role our investment portfolios play in helping them achieve their goals.

And so, the world of Insurance 4.0 is not just one of new products covering new risks, but a whole new conception of what insurance can be and do. Some say that in the future, all companies will be technology companies. If that is even close to being true, then insurance companies, which run on information, must surely be technology companies to succeed.

But can they all be? No. Some don’t have the innovation mindset to adapt. I know of many insurers that employ only slightly modernized versions of the same processes that have been around for well over 100, and have yet survived. They will continue to try to muddle along until forced. Capital providers to stock insurers are getting impatient about returns, and so merger and acquisition activity is increasing. Few small insurers can afford to become state-of-the-art technology providers, and many will have to seek stronger partners. Most mutual companies, which do not have those demanding investors to answer to, will just carry on, but lose share of market to faster-moving competitors. I believe Insurance 4.0 will feature an accelerating consolidation of the global industry, driven by the technology leaders taking over technology laggards.

I also believe that more and better utilization of data by insurers will lead to better pricing and better loss reserving, reducing the amplitude of underwriting cycles. This, in turn, will result in the industry becoming less of a frequency business and more of a severity provider, a tail-risk provider. The greatest value of the industry to its customers will become having the ability to better forecast and the capacity to provide for extreme weather events and other large losses. Examples would include cyber, environmental and terrorism/civil unrest. This is yet another argument for industry consolidation around fewer, bigger, tech-savvy insurers, and for an even greater role for funding from the capital markets.

Another rapidly emerging concept of Insurance 4.0 is the industry’s role in loss mitigation. I’m shocked to find that many people still think our industry exists solely to pay money to people after bad things happen. In fact, the industry’s role in mitigating and even preventing losses before they occur is the key reason for the rapid rise of public/private partnerships and invitations by governments to help them anticipate and reduce, not just pay for, losses.

As an example, I participated in this year’s G20 meetings in Argentina , where, for the first time ever, a dedicated insurance summit was held. Industry and governments explored opportunities to work together better to reduce losses any way possible. It is becoming widely understood that every dollar spent on loss mitigation and prevention by governments saves five dollars of post-event spending.

This gets to a basic disconnect that the industry must come to grips with: Insurers basically want to sell protection for when losses occur, which they have done for centuries now. Customers, on the other hand, now want to buy loss prevention and mitigation, in the form of broader advisory services.

If real customer-centricity is to be achieved, making this fundamental shift in the business model of how the industry meets customer needs would truly mean we have reached Insurance 4.0!

Technological disruption: artificial intelligence, blockchain, telematics, genomics, the Internet of Things.

Economic disruption: imagine: AirBnB is now the #1 hotel company, Uber is the #1 taxi company, big stores and shopping malls are fighting for their lives. Sears, the Amazon of the 20th century, recently declared bankruptcy, and many traditional bricks-and-morter retailers are threatened.

Social disruption: some parts of the world are aging rapidly, with attendant retirement savings and healthcare challenges, while other parts, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, have more young people than jobs; people want to be able to use things without necessarily owning them; concepts of work are changing; income equality and gender equality are major issues.

While the concept of a Fourth Industrial Revolution is now widely discussed, I would like to describe the Fourth Insurance Revolution as I see it. Like the eras of the four industrial revolutions, there have been three previous periods in insurance industry history that are somewhat similar to the evolution of the industrial world.

The first era, which I call Insurance 1.0, began logically enough in the parts of the world that were the cradles of civilization, the Middle East and Asia.

See also: Industry 4.0: What It Means for Insurance

As far back as the second and third millennia BC, traveling Chinese merchants practiced an early form of risk management by distributing their wares among numerous ships and different trade routes, to minimize losses along the way. In Babylonia, merchants receiving a loan to ship goods paid the lender an additional fee that would cancel the loan if the goods were somehow lost – credit insurance. This form of coverage is even memorialized in the Code of Hammurabi. The Greeks and Romans introduced the origins of life and health insurance when they created guilds called benevolent societies, to pay family members for funeral expenses of deceased members. These are our industry’s beginnings.

Insurance 2.0 as I see it was the introduction of the first actual insurance contracts. These were developed in Genoa, Italy, in the 14th century and related to marine insurance for goods in transit. This was a formalization of the earlier concepts employed in the Insurance 1.0 period.

Our industry matured greatly in the 17th century, into what I deem Insurance 3.0, a major leap forward.

Much of the accelerated formalization of insurance was stimulated by the Great Fire of London in 1666. This enormous conflagration destroyed nearly 70,000 of the city’s 80,000 residences, and gave rise to urgent risk management and insurance planning. Property and fire insurance as we know it was launched by Nicholas Barbon in London in 1681. Around the same time, French mathematicians Blaise Pascal and Henri de Fermat conducted loss probability studies that resulted in the first actuarial tables. Insurance became an empirically based enterprise, and became widely understood to be a prudent expenditure for businesses and families.

With that brief history of the evolution of our industry, let’s now move on to insurance in the 21st century: Insurance 4.0

In my view, most of the change in the industry since Insurance 3.0 up until the present has been incremental. Broader product lines, more distribution channels and, recently, the first elements of digitization. But what’s happening now is fundamentally different. The basic function and processes of insurance are being disrupted at an accelerating pace.

So let me now present some of the issues and implications of change in the industry, what Insurance 4.0 looks like. I’ll start by making some comments on the insurance industry of today.

Of course much of the rapid change taking place now and defining Insurance 4.0 is related to technology. The insurance industry’s raw material is data. Data not only to make underwriting and loss reserving judgments, but increasingly to manage virtually every business process in the insurance value chain. Data is valuable. But how can insurers successfully plan and manage data when, as Science Daily magazine tells us, 90% of all the data in the world has been generated in the last two years?! How do we use this avalanche of data to make sound business decisions? More data does not inevitably lead to better decisions.

One promising set of tools: Artificial intelligence and machine learning, which represent a quantum leap from the predictive modeling insurers have been using over the past decade.

Moving rapidly from applications in high-frequency, low-severity lines like auto and home insurance, AI capabilities are now employed in more complex commercial lines, and already show evidence of having real underwriting and loss reserving value.

Skeptical about whether this can work in complex cases? Let me give you an AI example. A few years ago, a computer beat the world chess champion. Well, some said, that’s fine, but it will be a long time before a computer can beat a top Go player. As many of you know, Go is a complex Asian game played on a 19-by-19 grid, with more possible configurations than the number of atoms in the known universe. Google’s Deep Mind Lab computer input all the Go games ever recorded, over a 1,000-plus year span. After playing 4.9 million games against itself in a three-day period to learn, the computer immediately beat the world’s best Go player in a live game.

What’s more thought-provoking, though, is what happened next. Putting aside the input of historical game results, Google just uploaded the basic rules of the game – no experience data. This new program, AlphaGoZero, became expert simply from learning first principles alone, without any human knowledge or experience input. Does anyone still think sophisticated underwriting or loss reserving is beyond the capability of modern computers? I don’t.

Entrepreneurs have expanded the way technology can influence the insurance value chain to create an ecosystem we call insurtech. Leveraging off fintech’s huge impact on the banking and payments world, insurtech companies, which now number more than 100,000, are innovating in every insurance company department. Investments in them have grown by leaps and bounds. Insurtech attracted about $140 million in funding in 2011, $275 million in 2013, $2.7 billion by 2015 and more than $4 billion last year.

Insurtech products and services address product development, marketing, pricing, claims and distribution, especially reducing policy acquisition costs, and have been much more focused on nonlife insurance (especially personal lines) than life and health insurance to date. Up until now, insurtech ventures have tended not to displace the incumbent insurers, but have been invested in or acquired by them to enhance their existing operations.

Much of the industry’s current expanded use of technology, including insurtech, is focused on customer interface and the customer experience. It has always been said that an industry can’t disrupt itself; that disruption always comes from the outside. Not surprisingly, then, insurance policyholders and potential customers have had their expectations of customer experience elevated by their interaction with other product and service providers. No longer do they measure their satisfaction against other insurance companies. They want the kind of experience they get from Apple, Alibaba, Amazon, Starbucks and the like. They want mobile, 24/7, personalized service. Most insurers today are simply not capable of delivering this. They lack both the innovation mindsets and the IT budgets to deliver a 21st century insurance customer experience, and they will lose share of market to those companies that do.

Another element of change in today’s insurance business is the emergence of public/private partnerships. More sovereign and sub-sovereign governments have come to realize that they are effectively the insurers of last resort when catastrophes strike.

Efforts are accelerating to narrow the protection gap between total economic losses and the portion covered by insurance.

Because the governments often end up paying directly or indirectly for disasters, and their citizens feel their brunt in terms of higher taxes or reduced services, governments now increasingly seek to partner with insurers. This is a positive development for the industry, one that presents both an enormous growth opportunity and a benefit to society.

Recent years have seen the launch of the African Risk Capacity, the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Fund and the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Insurance Company. All are regional public/private partnerships, and all are enabled by technology-driven parametric triggers. Others are in the works, facilities designed to address a range of perils including flood pools, terrorism pools and the like, best managed by governments and industry working together.

The “lower interest rates for longer” world we live in presents major challenges for investing the assets that support our policy liabilities. Insurers can no longer simply commit the bulk of their portfolios to investment grade corporate and government debt. Such a strategy just isn’t sufficient to pay claims and provide an adequate return on capital now.

Insurers and the asset managers who serve them have responded by changing their asset mix, to increase allocations to higher-return, not-much-higher-risk securities (let's hope). More equities. Structured products and bundles of loans. Private equity funds. And recently, infrastructure debt, in both developed and emerging markets.

Portfolio yields are rising, but only time will tell whether these new investment allocations provide an appropriate margin of safety in more turbulent market conditions. It’s really too soon to tell if the industry’s investments have become riskier, or if insurers have simply better understood the true risks of 21st century investing.

A more subtle but truly profound change in Insurance 4.0 is the industry’s focus on talent. I’ve been in the insurance business more than 47 years, and I can say with complete confidence that insurers have never remotely spent as much time, money and thought on developing their future leadership as today. There has always been talk about this, but the action has never before matched the rhetoric.

With approximately 25% of the industry’s top management retiring in the next five years, as Baby Boomers retire in large numbers, the urgency of talent development has finally dawned on CEOs and even boards. Competing for top young talent isn’t easy. The lure of technology firms, entertainment, investment banking and other seemingly more exciting career paths is undeniable. But insurers have to try to attract at least some of the best, because our industry’s role in society is so critical, and the talent gap is large and growing.

For the first time in my career, CEOs bring up their programs for attracting, developing and retaining talent without me asking them first. More and more describe carefully thought-out programs that are so strategically important that they have high visibility with their boards. Believe me, this is a real change. These are the companies that will thrive over the long term.

All of these initiatives, in technology, in the customer experience, in public/private partnerships, in new investment approaches as well as in talent development, exemplify Insurance 4.0. Not just doing what we have always done, hoping to be somewhat better, but developing new tools to address new challenges, new opportunities and new competitors from within and without the industry.

This is because insurers are the financial first responders in this risky world. We rebuild communities and homes after disasters, we provide financial stability when families lose loved ones and we invest to build economies around the world, and in Insurance 4.0 we do it faster and better.

As numerous and daunting as the changes of today are for the insurance industry, there will be more and greater challenges in the industry of tomorrow.

The accelerating pace of change in our world not only demands new products, but presents entirely new forms of risk, as well. I referred earlier to the three generic kinds of disruption we are witnessing. Each of them carries new risk exposure the likes of which our industry has not dealt with before.

Technology disruption, for example, presents a host of new risks related to our connected world. Insurers are struggling to find their place as autonomous vehicles loom large in our future. What does this mean for the motor insurance business, the industry’s largest line of coverage? Will auto manufacturers simply bypass the insurance industry and go directly to the capital markets for their enormous coverage needs? Will commercial drones inspecting property damage claims improve workflow and reduce reliance on human error?

How will blockchain reduce expenses? The InsureWave project developed by EY, Maersk, Willis and GuardTime promises to slash marine insurance expense ratios by approximately 10 points! Other blockchain applications are in the works, and industry consortia like The Institutes’ Risk Block Alliance are finding new processes to save and make money every day now.

Finally, cyber risk represents the world’s first truly global peril, including a cascading potential due to our connectedness. Clearly, there is premium growth potential in cyber, but the early promoters of long-term-care insurance might remind us that revenue growth potential does not necessarily portend long-term profit. Current cyber combined ratios are running around 60%. True loss experience, though, will take years or decades to be fully understood.

Economic disruption also presents new challenges and opportunities for insurers going forward. Who will be the insureds of the future? How does a company insure Uber or AirBnB, let alone the people who use them and the facilities they work with? How does the collapse of traditional industry customers like retailers, coal companies and other industries that dominated the 20th century affect insurers? And by the way, is the industry prepared to cut 25% to 50% of its non-customer-facing jobs over the next decade as a “benefit” of AI and robotics? Some of the internal workforce can become part of the “hybrid system,” the human overlords who write and work alongside the smart systems to make their ultimate decisions, but not many.

Social disruption is also a source of new risks. For nonlife insurers, reputation risk and privacy risk have enormous potential exposures, and little existing loss data to make rates. It’s much too soon to tell if providing coverage for these exposures will be viable or not.

What are the insurance implications of the sharing economy, where more people want the ability to use things without owning them? Usage based insurance is gaining popularity, but also has the potential to significantly reduce premium volume. What about the “gig economy,” where many people hold several part-time jobs and no full-time job (meaning no benefits)?

And how will life and health insurers cope with a rapidly aging developed world? Retirement savings is a looming crisis. And even if we manage to avoid pandemics (consider: If the Spanish Flu of 1918 occurred today, it could kill 400 million people), what are the implications of a hotter and more polluted planet for healthcare? Will wearable devices driving the Internet of Things provide a cornucopia of information to enable better health outcomes?

See also: Insurance Service Rates Zero Stars

And what of the big issue: climate change? Both the World Economic Forum and Lloyd’s of London define climate change as a top socio-economic risk to our society. Climate risk is now considered a core strategic issue by governments, businesses, even the military. Certainly for the insurance industry, adaptation and mitigation, the need to make future provisions for inevitable damage, and send pricing signals to insureds of the true cost of risk, is a defining issue of our time.

In a broad way, Insurance 4.0 means the industry is becoming part of an ecosystem of connected and communicating sectors that are symbiotic, not as “B to B,” business to business, or “B to C,” business to consumer, but “E to E”: everything to everybody, where the information exchange benefits all participants, but is not equally understood by all parties. The information flow is asymmetrical. We can all agree that reducing risk in our world is a good thing for society, but, if risk is materially reduced, will the size and relevance of our industry then shrink?

A few words are also in order about the political capital the insurance industry possesses. I have written herein mostly about the risk management side of our business, and indeed it is the very reason we are in business. But even in a time of increasing public/private partnerships seeking to mitigate and remediate natural disasters, politicians and policy makers primarily ascribe our industry’s power and influence to our investment portfolios.

Globally, the industry has over $35 trillion of invested assets. Assets that are invested in companies’ domiciliary countries’ government bond markets and are critical to those countries.

Assets invested in their stock and corporate bond markets, as well. And now, insurers’ role, along with pension funds, as the only true long-term investors, means they are vital to infrastructure funding. Growth projects for the emerging world, and reconstruction financing for the developed world. This is what gets the attention of policymakers. And so this attribute is what we must nurture and promote to enhance our stature. Our most promising avenue to high esteem with policymakers is by securing their understanding of the vital role our investment portfolios play in helping them achieve their goals.

And so, the world of Insurance 4.0 is not just one of new products covering new risks, but a whole new conception of what insurance can be and do. Some say that in the future, all companies will be technology companies. If that is even close to being true, then insurance companies, which run on information, must surely be technology companies to succeed.

But can they all be? No. Some don’t have the innovation mindset to adapt. I know of many insurers that employ only slightly modernized versions of the same processes that have been around for well over 100, and have yet survived. They will continue to try to muddle along until forced. Capital providers to stock insurers are getting impatient about returns, and so merger and acquisition activity is increasing. Few small insurers can afford to become state-of-the-art technology providers, and many will have to seek stronger partners. Most mutual companies, which do not have those demanding investors to answer to, will just carry on, but lose share of market to faster-moving competitors. I believe Insurance 4.0 will feature an accelerating consolidation of the global industry, driven by the technology leaders taking over technology laggards.

I also believe that more and better utilization of data by insurers will lead to better pricing and better loss reserving, reducing the amplitude of underwriting cycles. This, in turn, will result in the industry becoming less of a frequency business and more of a severity provider, a tail-risk provider. The greatest value of the industry to its customers will become having the ability to better forecast and the capacity to provide for extreme weather events and other large losses. Examples would include cyber, environmental and terrorism/civil unrest. This is yet another argument for industry consolidation around fewer, bigger, tech-savvy insurers, and for an even greater role for funding from the capital markets.

Another rapidly emerging concept of Insurance 4.0 is the industry’s role in loss mitigation. I’m shocked to find that many people still think our industry exists solely to pay money to people after bad things happen. In fact, the industry’s role in mitigating and even preventing losses before they occur is the key reason for the rapid rise of public/private partnerships and invitations by governments to help them anticipate and reduce, not just pay for, losses.

As an example, I participated in this year’s G20 meetings in Argentina , where, for the first time ever, a dedicated insurance summit was held. Industry and governments explored opportunities to work together better to reduce losses any way possible. It is becoming widely understood that every dollar spent on loss mitigation and prevention by governments saves five dollars of post-event spending.

This gets to a basic disconnect that the industry must come to grips with: Insurers basically want to sell protection for when losses occur, which they have done for centuries now. Customers, on the other hand, now want to buy loss prevention and mitigation, in the form of broader advisory services.

If real customer-centricity is to be achieved, making this fundamental shift in the business model of how the industry meets customer needs would truly mean we have reached Insurance 4.0!Insurance and Fourth Industrial Revolution

The accelerating change in our world not only demands new products, but presents entirely new forms of risk, as well, for Insurance 4.0.

Technological disruption: artificial intelligence, blockchain, telematics, genomics, the Internet of Things.

Economic disruption: imagine: AirBnB is now the #1 hotel company, Uber is the #1 taxi company, big stores and shopping malls are fighting for their lives. Sears, the Amazon of the 20th century, recently declared bankruptcy, and many traditional bricks-and-morter retailers are threatened.

Social disruption: some parts of the world are aging rapidly, with attendant retirement savings and healthcare challenges, while other parts, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, have more young people than jobs; people want to be able to use things without necessarily owning them; concepts of work are changing; income equality and gender equality are major issues.

While the concept of a Fourth Industrial Revolution is now widely discussed, I would like to describe the Fourth Insurance Revolution as I see it. Like the eras of the four industrial revolutions, there have been three previous periods in insurance industry history that are somewhat similar to the evolution of the industrial world.

The first era, which I call Insurance 1.0, began logically enough in the parts of the world that were the cradles of civilization, the Middle East and Asia.

See also: Industry 4.0: What It Means for Insurance

As far back as the second and third millennia BC, traveling Chinese merchants practiced an early form of risk management by distributing their wares among numerous ships and different trade routes, to minimize losses along the way. In Babylonia, merchants receiving a loan to ship goods paid the lender an additional fee that would cancel the loan if the goods were somehow lost – credit insurance. This form of coverage is even memorialized in the Code of Hammurabi. The Greeks and Romans introduced the origins of life and health insurance when they created guilds called benevolent societies, to pay family members for funeral expenses of deceased members. These are our industry’s beginnings.

Insurance 2.0 as I see it was the introduction of the first actual insurance contracts. These were developed in Genoa, Italy, in the 14th century and related to marine insurance for goods in transit. This was a formalization of the earlier concepts employed in the Insurance 1.0 period.

Our industry matured greatly in the 17th century, into what I deem Insurance 3.0, a major leap forward.

Much of the accelerated formalization of insurance was stimulated by the Great Fire of London in 1666. This enormous conflagration destroyed nearly 70,000 of the city’s 80,000 residences, and gave rise to urgent risk management and insurance planning. Property and fire insurance as we know it was launched by Nicholas Barbon in London in 1681. Around the same time, French mathematicians Blaise Pascal and Henri de Fermat conducted loss probability studies that resulted in the first actuarial tables. Insurance became an empirically based enterprise, and became widely understood to be a prudent expenditure for businesses and families.

With that brief history of the evolution of our industry, let’s now move on to insurance in the 21st century: Insurance 4.0

In my view, most of the change in the industry since Insurance 3.0 up until the present has been incremental. Broader product lines, more distribution channels and, recently, the first elements of digitization. But what’s happening now is fundamentally different. The basic function and processes of insurance are being disrupted at an accelerating pace.

So let me now present some of the issues and implications of change in the industry, what Insurance 4.0 looks like. I’ll start by making some comments on the insurance industry of today.

Of course much of the rapid change taking place now and defining Insurance 4.0 is related to technology. The insurance industry’s raw material is data. Data not only to make underwriting and loss reserving judgments, but increasingly to manage virtually every business process in the insurance value chain. Data is valuable. But how can insurers successfully plan and manage data when, as Science Daily magazine tells us, 90% of all the data in the world has been generated in the last two years?! How do we use this avalanche of data to make sound business decisions? More data does not inevitably lead to better decisions.

One promising set of tools: Artificial intelligence and machine learning, which represent a quantum leap from the predictive modeling insurers have been using over the past decade.

Moving rapidly from applications in high-frequency, low-severity lines like auto and home insurance, AI capabilities are now employed in more complex commercial lines, and already show evidence of having real underwriting and loss reserving value.

Skeptical about whether this can work in complex cases? Let me give you an AI example. A few years ago, a computer beat the world chess champion. Well, some said, that’s fine, but it will be a long time before a computer can beat a top Go player. As many of you know, Go is a complex Asian game played on a 19-by-19 grid, with more possible configurations than the number of atoms in the known universe. Google’s Deep Mind Lab computer input all the Go games ever recorded, over a 1,000-plus year span. After playing 4.9 million games against itself in a three-day period to learn, the computer immediately beat the world’s best Go player in a live game.

What’s more thought-provoking, though, is what happened next. Putting aside the input of historical game results, Google just uploaded the basic rules of the game – no experience data. This new program, AlphaGoZero, became expert simply from learning first principles alone, without any human knowledge or experience input. Does anyone still think sophisticated underwriting or loss reserving is beyond the capability of modern computers? I don’t.

Entrepreneurs have expanded the way technology can influence the insurance value chain to create an ecosystem we call insurtech. Leveraging off fintech’s huge impact on the banking and payments world, insurtech companies, which now number more than 100,000, are innovating in every insurance company department. Investments in them have grown by leaps and bounds. Insurtech attracted about $140 million in funding in 2011, $275 million in 2013, $2.7 billion by 2015 and more than $4 billion last year.

Insurtech products and services address product development, marketing, pricing, claims and distribution, especially reducing policy acquisition costs, and have been much more focused on nonlife insurance (especially personal lines) than life and health insurance to date. Up until now, insurtech ventures have tended not to displace the incumbent insurers, but have been invested in or acquired by them to enhance their existing operations.

Much of the industry’s current expanded use of technology, including insurtech, is focused on customer interface and the customer experience. It has always been said that an industry can’t disrupt itself; that disruption always comes from the outside. Not surprisingly, then, insurance policyholders and potential customers have had their expectations of customer experience elevated by their interaction with other product and service providers. No longer do they measure their satisfaction against other insurance companies. They want the kind of experience they get from Apple, Alibaba, Amazon, Starbucks and the like. They want mobile, 24/7, personalized service. Most insurers today are simply not capable of delivering this. They lack both the innovation mindsets and the IT budgets to deliver a 21st century insurance customer experience, and they will lose share of market to those companies that do.

Another element of change in today’s insurance business is the emergence of public/private partnerships. More sovereign and sub-sovereign governments have come to realize that they are effectively the insurers of last resort when catastrophes strike.

Efforts are accelerating to narrow the protection gap between total economic losses and the portion covered by insurance.

Because the governments often end up paying directly or indirectly for disasters, and their citizens feel their brunt in terms of higher taxes or reduced services, governments now increasingly seek to partner with insurers. This is a positive development for the industry, one that presents both an enormous growth opportunity and a benefit to society.

Recent years have seen the launch of the African Risk Capacity, the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Fund and the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Insurance Company. All are regional public/private partnerships, and all are enabled by technology-driven parametric triggers. Others are in the works, facilities designed to address a range of perils including flood pools, terrorism pools and the like, best managed by governments and industry working together.

The “lower interest rates for longer” world we live in presents major challenges for investing the assets that support our policy liabilities. Insurers can no longer simply commit the bulk of their portfolios to investment grade corporate and government debt. Such a strategy just isn’t sufficient to pay claims and provide an adequate return on capital now.

Insurers and the asset managers who serve them have responded by changing their asset mix, to increase allocations to higher-return, not-much-higher-risk securities (let's hope). More equities. Structured products and bundles of loans. Private equity funds. And recently, infrastructure debt, in both developed and emerging markets.

Portfolio yields are rising, but only time will tell whether these new investment allocations provide an appropriate margin of safety in more turbulent market conditions. It’s really too soon to tell if the industry’s investments have become riskier, or if insurers have simply better understood the true risks of 21st century investing.

A more subtle but truly profound change in Insurance 4.0 is the industry’s focus on talent. I’ve been in the insurance business more than 47 years, and I can say with complete confidence that insurers have never remotely spent as much time, money and thought on developing their future leadership as today. There has always been talk about this, but the action has never before matched the rhetoric.

With approximately 25% of the industry’s top management retiring in the next five years, as Baby Boomers retire in large numbers, the urgency of talent development has finally dawned on CEOs and even boards. Competing for top young talent isn’t easy. The lure of technology firms, entertainment, investment banking and other seemingly more exciting career paths is undeniable. But insurers have to try to attract at least some of the best, because our industry’s role in society is so critical, and the talent gap is large and growing.

For the first time in my career, CEOs bring up their programs for attracting, developing and retaining talent without me asking them first. More and more describe carefully thought-out programs that are so strategically important that they have high visibility with their boards. Believe me, this is a real change. These are the companies that will thrive over the long term.

All of these initiatives, in technology, in the customer experience, in public/private partnerships, in new investment approaches as well as in talent development, exemplify Insurance 4.0. Not just doing what we have always done, hoping to be somewhat better, but developing new tools to address new challenges, new opportunities and new competitors from within and without the industry.

This is because insurers are the financial first responders in this risky world. We rebuild communities and homes after disasters, we provide financial stability when families lose loved ones and we invest to build economies around the world, and in Insurance 4.0 we do it faster and better.

As numerous and daunting as the changes of today are for the insurance industry, there will be more and greater challenges in the industry of tomorrow.

The accelerating pace of change in our world not only demands new products, but presents entirely new forms of risk, as well. I referred earlier to the three generic kinds of disruption we are witnessing. Each of them carries new risk exposure the likes of which our industry has not dealt with before.

Technology disruption, for example, presents a host of new risks related to our connected world. Insurers are struggling to find their place as autonomous vehicles loom large in our future. What does this mean for the motor insurance business, the industry’s largest line of coverage? Will auto manufacturers simply bypass the insurance industry and go directly to the capital markets for their enormous coverage needs? Will commercial drones inspecting property damage claims improve workflow and reduce reliance on human error?

How will blockchain reduce expenses? The InsureWave project developed by EY, Maersk, Willis and GuardTime promises to slash marine insurance expense ratios by approximately 10 points! Other blockchain applications are in the works, and industry consortia like The Institutes’ Risk Block Alliance are finding new processes to save and make money every day now.

Finally, cyber risk represents the world’s first truly global peril, including a cascading potential due to our connectedness. Clearly, there is premium growth potential in cyber, but the early promoters of long-term-care insurance might remind us that revenue growth potential does not necessarily portend long-term profit. Current cyber combined ratios are running around 60%. True loss experience, though, will take years or decades to be fully understood.

Economic disruption also presents new challenges and opportunities for insurers going forward. Who will be the insureds of the future? How does a company insure Uber or AirBnB, let alone the people who use them and the facilities they work with? How does the collapse of traditional industry customers like retailers, coal companies and other industries that dominated the 20th century affect insurers? And by the way, is the industry prepared to cut 25% to 50% of its non-customer-facing jobs over the next decade as a “benefit” of AI and robotics? Some of the internal workforce can become part of the “hybrid system,” the human overlords who write and work alongside the smart systems to make their ultimate decisions, but not many.

Social disruption is also a source of new risks. For nonlife insurers, reputation risk and privacy risk have enormous potential exposures, and little existing loss data to make rates. It’s much too soon to tell if providing coverage for these exposures will be viable or not.

What are the insurance implications of the sharing economy, where more people want the ability to use things without owning them? Usage based insurance is gaining popularity, but also has the potential to significantly reduce premium volume. What about the “gig economy,” where many people hold several part-time jobs and no full-time job (meaning no benefits)?

And how will life and health insurers cope with a rapidly aging developed world? Retirement savings is a looming crisis. And even if we manage to avoid pandemics (consider: If the Spanish Flu of 1918 occurred today, it could kill 400 million people), what are the implications of a hotter and more polluted planet for healthcare? Will wearable devices driving the Internet of Things provide a cornucopia of information to enable better health outcomes?

See also: Insurance Service Rates Zero Stars

And what of the big issue: climate change? Both the World Economic Forum and Lloyd’s of London define climate change as a top socio-economic risk to our society. Climate risk is now considered a core strategic issue by governments, businesses, even the military. Certainly for the insurance industry, adaptation and mitigation, the need to make future provisions for inevitable damage, and send pricing signals to insureds of the true cost of risk, is a defining issue of our time.

In a broad way, Insurance 4.0 means the industry is becoming part of an ecosystem of connected and communicating sectors that are symbiotic, not as “B to B,” business to business, or “B to C,” business to consumer, but “E to E”: everything to everybody, where the information exchange benefits all participants, but is not equally understood by all parties. The information flow is asymmetrical. We can all agree that reducing risk in our world is a good thing for society, but, if risk is materially reduced, will the size and relevance of our industry then shrink?

A few words are also in order about the political capital the insurance industry possesses. I have written herein mostly about the risk management side of our business, and indeed it is the very reason we are in business. But even in a time of increasing public/private partnerships seeking to mitigate and remediate natural disasters, politicians and policy makers primarily ascribe our industry’s power and influence to our investment portfolios.

Globally, the industry has over $35 trillion of invested assets. Assets that are invested in companies’ domiciliary countries’ government bond markets and are critical to those countries.

Assets invested in their stock and corporate bond markets, as well. And now, insurers’ role, along with pension funds, as the only true long-term investors, means they are vital to infrastructure funding. Growth projects for the emerging world, and reconstruction financing for the developed world. This is what gets the attention of policymakers. And so this attribute is what we must nurture and promote to enhance our stature. Our most promising avenue to high esteem with policymakers is by securing their understanding of the vital role our investment portfolios play in helping them achieve their goals.

And so, the world of Insurance 4.0 is not just one of new products covering new risks, but a whole new conception of what insurance can be and do. Some say that in the future, all companies will be technology companies. If that is even close to being true, then insurance companies, which run on information, must surely be technology companies to succeed.

But can they all be? No. Some don’t have the innovation mindset to adapt. I know of many insurers that employ only slightly modernized versions of the same processes that have been around for well over 100, and have yet survived. They will continue to try to muddle along until forced. Capital providers to stock insurers are getting impatient about returns, and so merger and acquisition activity is increasing. Few small insurers can afford to become state-of-the-art technology providers, and many will have to seek stronger partners. Most mutual companies, which do not have those demanding investors to answer to, will just carry on, but lose share of market to faster-moving competitors. I believe Insurance 4.0 will feature an accelerating consolidation of the global industry, driven by the technology leaders taking over technology laggards.

I also believe that more and better utilization of data by insurers will lead to better pricing and better loss reserving, reducing the amplitude of underwriting cycles. This, in turn, will result in the industry becoming less of a frequency business and more of a severity provider, a tail-risk provider. The greatest value of the industry to its customers will become having the ability to better forecast and the capacity to provide for extreme weather events and other large losses. Examples would include cyber, environmental and terrorism/civil unrest. This is yet another argument for industry consolidation around fewer, bigger, tech-savvy insurers, and for an even greater role for funding from the capital markets.

Another rapidly emerging concept of Insurance 4.0 is the industry’s role in loss mitigation. I’m shocked to find that many people still think our industry exists solely to pay money to people after bad things happen. In fact, the industry’s role in mitigating and even preventing losses before they occur is the key reason for the rapid rise of public/private partnerships and invitations by governments to help them anticipate and reduce, not just pay for, losses.

As an example, I participated in this year’s G20 meetings in Argentina , where, for the first time ever, a dedicated insurance summit was held. Industry and governments explored opportunities to work together better to reduce losses any way possible. It is becoming widely understood that every dollar spent on loss mitigation and prevention by governments saves five dollars of post-event spending.

This gets to a basic disconnect that the industry must come to grips with: Insurers basically want to sell protection for when losses occur, which they have done for centuries now. Customers, on the other hand, now want to buy loss prevention and mitigation, in the form of broader advisory services.

If real customer-centricity is to be achieved, making this fundamental shift in the business model of how the industry meets customer needs would truly mean we have reached Insurance 4.0!

Technological disruption: artificial intelligence, blockchain, telematics, genomics, the Internet of Things.

Economic disruption: imagine: AirBnB is now the #1 hotel company, Uber is the #1 taxi company, big stores and shopping malls are fighting for their lives. Sears, the Amazon of the 20th century, recently declared bankruptcy, and many traditional bricks-and-morter retailers are threatened.

Social disruption: some parts of the world are aging rapidly, with attendant retirement savings and healthcare challenges, while other parts, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, have more young people than jobs; people want to be able to use things without necessarily owning them; concepts of work are changing; income equality and gender equality are major issues.

While the concept of a Fourth Industrial Revolution is now widely discussed, I would like to describe the Fourth Insurance Revolution as I see it. Like the eras of the four industrial revolutions, there have been three previous periods in insurance industry history that are somewhat similar to the evolution of the industrial world.

The first era, which I call Insurance 1.0, began logically enough in the parts of the world that were the cradles of civilization, the Middle East and Asia.

See also: Industry 4.0: What It Means for Insurance

As far back as the second and third millennia BC, traveling Chinese merchants practiced an early form of risk management by distributing their wares among numerous ships and different trade routes, to minimize losses along the way. In Babylonia, merchants receiving a loan to ship goods paid the lender an additional fee that would cancel the loan if the goods were somehow lost – credit insurance. This form of coverage is even memorialized in the Code of Hammurabi. The Greeks and Romans introduced the origins of life and health insurance when they created guilds called benevolent societies, to pay family members for funeral expenses of deceased members. These are our industry’s beginnings.

Insurance 2.0 as I see it was the introduction of the first actual insurance contracts. These were developed in Genoa, Italy, in the 14th century and related to marine insurance for goods in transit. This was a formalization of the earlier concepts employed in the Insurance 1.0 period.

Our industry matured greatly in the 17th century, into what I deem Insurance 3.0, a major leap forward.

Much of the accelerated formalization of insurance was stimulated by the Great Fire of London in 1666. This enormous conflagration destroyed nearly 70,000 of the city’s 80,000 residences, and gave rise to urgent risk management and insurance planning. Property and fire insurance as we know it was launched by Nicholas Barbon in London in 1681. Around the same time, French mathematicians Blaise Pascal and Henri de Fermat conducted loss probability studies that resulted in the first actuarial tables. Insurance became an empirically based enterprise, and became widely understood to be a prudent expenditure for businesses and families.

With that brief history of the evolution of our industry, let’s now move on to insurance in the 21st century: Insurance 4.0

In my view, most of the change in the industry since Insurance 3.0 up until the present has been incremental. Broader product lines, more distribution channels and, recently, the first elements of digitization. But what’s happening now is fundamentally different. The basic function and processes of insurance are being disrupted at an accelerating pace.

So let me now present some of the issues and implications of change in the industry, what Insurance 4.0 looks like. I’ll start by making some comments on the insurance industry of today.

Of course much of the rapid change taking place now and defining Insurance 4.0 is related to technology. The insurance industry’s raw material is data. Data not only to make underwriting and loss reserving judgments, but increasingly to manage virtually every business process in the insurance value chain. Data is valuable. But how can insurers successfully plan and manage data when, as Science Daily magazine tells us, 90% of all the data in the world has been generated in the last two years?! How do we use this avalanche of data to make sound business decisions? More data does not inevitably lead to better decisions.

One promising set of tools: Artificial intelligence and machine learning, which represent a quantum leap from the predictive modeling insurers have been using over the past decade.

Moving rapidly from applications in high-frequency, low-severity lines like auto and home insurance, AI capabilities are now employed in more complex commercial lines, and already show evidence of having real underwriting and loss reserving value.

Skeptical about whether this can work in complex cases? Let me give you an AI example. A few years ago, a computer beat the world chess champion. Well, some said, that’s fine, but it will be a long time before a computer can beat a top Go player. As many of you know, Go is a complex Asian game played on a 19-by-19 grid, with more possible configurations than the number of atoms in the known universe. Google’s Deep Mind Lab computer input all the Go games ever recorded, over a 1,000-plus year span. After playing 4.9 million games against itself in a three-day period to learn, the computer immediately beat the world’s best Go player in a live game.

What’s more thought-provoking, though, is what happened next. Putting aside the input of historical game results, Google just uploaded the basic rules of the game – no experience data. This new program, AlphaGoZero, became expert simply from learning first principles alone, without any human knowledge or experience input. Does anyone still think sophisticated underwriting or loss reserving is beyond the capability of modern computers? I don’t.

Entrepreneurs have expanded the way technology can influence the insurance value chain to create an ecosystem we call insurtech. Leveraging off fintech’s huge impact on the banking and payments world, insurtech companies, which now number more than 100,000, are innovating in every insurance company department. Investments in them have grown by leaps and bounds. Insurtech attracted about $140 million in funding in 2011, $275 million in 2013, $2.7 billion by 2015 and more than $4 billion last year.

Insurtech products and services address product development, marketing, pricing, claims and distribution, especially reducing policy acquisition costs, and have been much more focused on nonlife insurance (especially personal lines) than life and health insurance to date. Up until now, insurtech ventures have tended not to displace the incumbent insurers, but have been invested in or acquired by them to enhance their existing operations.

Much of the industry’s current expanded use of technology, including insurtech, is focused on customer interface and the customer experience. It has always been said that an industry can’t disrupt itself; that disruption always comes from the outside. Not surprisingly, then, insurance policyholders and potential customers have had their expectations of customer experience elevated by their interaction with other product and service providers. No longer do they measure their satisfaction against other insurance companies. They want the kind of experience they get from Apple, Alibaba, Amazon, Starbucks and the like. They want mobile, 24/7, personalized service. Most insurers today are simply not capable of delivering this. They lack both the innovation mindsets and the IT budgets to deliver a 21st century insurance customer experience, and they will lose share of market to those companies that do.

Another element of change in today’s insurance business is the emergence of public/private partnerships. More sovereign and sub-sovereign governments have come to realize that they are effectively the insurers of last resort when catastrophes strike.

Efforts are accelerating to narrow the protection gap between total economic losses and the portion covered by insurance.

Because the governments often end up paying directly or indirectly for disasters, and their citizens feel their brunt in terms of higher taxes or reduced services, governments now increasingly seek to partner with insurers. This is a positive development for the industry, one that presents both an enormous growth opportunity and a benefit to society.

Recent years have seen the launch of the African Risk Capacity, the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Fund and the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Insurance Company. All are regional public/private partnerships, and all are enabled by technology-driven parametric triggers. Others are in the works, facilities designed to address a range of perils including flood pools, terrorism pools and the like, best managed by governments and industry working together.

The “lower interest rates for longer” world we live in presents major challenges for investing the assets that support our policy liabilities. Insurers can no longer simply commit the bulk of their portfolios to investment grade corporate and government debt. Such a strategy just isn’t sufficient to pay claims and provide an adequate return on capital now.

Insurers and the asset managers who serve them have responded by changing their asset mix, to increase allocations to higher-return, not-much-higher-risk securities (let's hope). More equities. Structured products and bundles of loans. Private equity funds. And recently, infrastructure debt, in both developed and emerging markets.

Portfolio yields are rising, but only time will tell whether these new investment allocations provide an appropriate margin of safety in more turbulent market conditions. It’s really too soon to tell if the industry’s investments have become riskier, or if insurers have simply better understood the true risks of 21st century investing.

A more subtle but truly profound change in Insurance 4.0 is the industry’s focus on talent. I’ve been in the insurance business more than 47 years, and I can say with complete confidence that insurers have never remotely spent as much time, money and thought on developing their future leadership as today. There has always been talk about this, but the action has never before matched the rhetoric.

With approximately 25% of the industry’s top management retiring in the next five years, as Baby Boomers retire in large numbers, the urgency of talent development has finally dawned on CEOs and even boards. Competing for top young talent isn’t easy. The lure of technology firms, entertainment, investment banking and other seemingly more exciting career paths is undeniable. But insurers have to try to attract at least some of the best, because our industry’s role in society is so critical, and the talent gap is large and growing.

For the first time in my career, CEOs bring up their programs for attracting, developing and retaining talent without me asking them first. More and more describe carefully thought-out programs that are so strategically important that they have high visibility with their boards. Believe me, this is a real change. These are the companies that will thrive over the long term.

All of these initiatives, in technology, in the customer experience, in public/private partnerships, in new investment approaches as well as in talent development, exemplify Insurance 4.0. Not just doing what we have always done, hoping to be somewhat better, but developing new tools to address new challenges, new opportunities and new competitors from within and without the industry.

This is because insurers are the financial first responders in this risky world. We rebuild communities and homes after disasters, we provide financial stability when families lose loved ones and we invest to build economies around the world, and in Insurance 4.0 we do it faster and better.

As numerous and daunting as the changes of today are for the insurance industry, there will be more and greater challenges in the industry of tomorrow.

The accelerating pace of change in our world not only demands new products, but presents entirely new forms of risk, as well. I referred earlier to the three generic kinds of disruption we are witnessing. Each of them carries new risk exposure the likes of which our industry has not dealt with before.

Technology disruption, for example, presents a host of new risks related to our connected world. Insurers are struggling to find their place as autonomous vehicles loom large in our future. What does this mean for the motor insurance business, the industry’s largest line of coverage? Will auto manufacturers simply bypass the insurance industry and go directly to the capital markets for their enormous coverage needs? Will commercial drones inspecting property damage claims improve workflow and reduce reliance on human error?

How will blockchain reduce expenses? The InsureWave project developed by EY, Maersk, Willis and GuardTime promises to slash marine insurance expense ratios by approximately 10 points! Other blockchain applications are in the works, and industry consortia like The Institutes’ Risk Block Alliance are finding new processes to save and make money every day now.

Finally, cyber risk represents the world’s first truly global peril, including a cascading potential due to our connectedness. Clearly, there is premium growth potential in cyber, but the early promoters of long-term-care insurance might remind us that revenue growth potential does not necessarily portend long-term profit. Current cyber combined ratios are running around 60%. True loss experience, though, will take years or decades to be fully understood.

Economic disruption also presents new challenges and opportunities for insurers going forward. Who will be the insureds of the future? How does a company insure Uber or AirBnB, let alone the people who use them and the facilities they work with? How does the collapse of traditional industry customers like retailers, coal companies and other industries that dominated the 20th century affect insurers? And by the way, is the industry prepared to cut 25% to 50% of its non-customer-facing jobs over the next decade as a “benefit” of AI and robotics? Some of the internal workforce can become part of the “hybrid system,” the human overlords who write and work alongside the smart systems to make their ultimate decisions, but not many.

Social disruption is also a source of new risks. For nonlife insurers, reputation risk and privacy risk have enormous potential exposures, and little existing loss data to make rates. It’s much too soon to tell if providing coverage for these exposures will be viable or not.

What are the insurance implications of the sharing economy, where more people want the ability to use things without owning them? Usage based insurance is gaining popularity, but also has the potential to significantly reduce premium volume. What about the “gig economy,” where many people hold several part-time jobs and no full-time job (meaning no benefits)?