How to Innovate With an Agency Partner

The key to true transformation and innovation isn’t just about investing in new technology. It’s about investing in new mindsets.

The key to true transformation and innovation isn’t just about investing in new technology. It’s about investing in new mindsets.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Emily Smith is the senior manager of communication and marketing at Cake & Arrow, a customer experience agency providing end-to-end digital products and services that help insurance companies redefine customer experience.

If AI can substantiate what a business adviser recommends, if that recommendation is brief yet bold, an insurer can succeed.

If actuaries are the elite of the insurance industry, members of a licensed class whose workaday language is intelligible to few but influential to many, then business advisers are the interpreters of a separate yet equally important language: data. More to the point, business advisers are an independent class—hence their advisory role—in which they do much more than translate data into reports. They use artificial intelligence (AI) to find intelligence worth analyzing. They use intelligence to advance wisdom, because it takes skill to convert ones and zeros into a message that is as concise as it is compelling; it takes a different class of advisers to actualize a future that is close but hard to see; it takes verbal facility and visual acuity to present the future—to make the future present—for the insurance industry.

AI is a tool to accelerate the future. That future depends on business advisers who can explain why what seems possible is not only probable but inevitable: that AI answers the needs of insurers. Making the answers accessible—proving the answers are right—is an issue of talent, not technology. According to Nick Chini, managing partner of Bainbridge, AI augments the models actuaries develop and business advisers deliver. Which is to say actuaries theorize scenarios—they quantify what may happen—while business advisers qualify how things will likely happen; how a business adviser infers what will happen; how the inferences a business adviser draws are the result of his fluency in data; how his education is more extensive, his expertise more expansive, his experience more exhaustive than that of a typical adviser. He is atypical, in a good way, because he represents the future of business advisory services. He may have a doctorate in linguistics or degrees in finance and computer science. He may be a former professor or a career academic. To paraphrase Chini, what matters most is a business adviser’s ability to advise: to add value by abandoning generalities—to stop generalizing, period—and offer specifics about the future direction of the insurance industry and the course insurers should follow. In this situation, AI acts like a compass. It points the way, telling a person where to go without revealing how or when that person should start his journey. See also: What to Look for in an AI Partner For an insurer to begin that journey, he must know the advice he receives is right. To advise, then, is to communicate—to communicate with clarity and conviction—so an insurer has no reason not to do the right thing, so an insurer believes in the rightness of his decision, so an insurer knows he is right. If business advisers can further what is right, to get insurers to more easily and expeditiously do the right thing before challenges arise, the insurance industry will benefit as a whole. If AI can substantiate what a business adviser recommends, if that recommendation is brief yet bold, if that business adviser can prove his recommendation is right, an insurer can succeed. Let us welcome the chance to read—and endorse—these recommendations.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Insurance is stuck with legacy technology, built for legacy processes, operated by a legacy mindset. Each problem must be corrected.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Aly Dhalla is the CEO/co-founder of Finaeo, a venture-backed insurtech startup that is reshaping insurance distribution to help independent advisers thrive in a digital era.

Insurers must solve the language problem to remain relevant, providing broad coverage for the cyber peril on the insurance lines it affects.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Philip Rosace is a cyber risk authority, inventor and patent holder of cyber risk quantification systems at Guidewire Software.

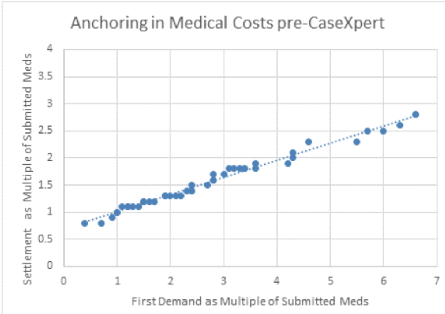

Data can let companies resist plaintiff attorneys' attempts to "anchor" negotiations with a high, initial demand.

To understand how medical costs influence, or anchor, the settlement, we looked at the relationship of first demands as a multiple of submitted medical costs (e.g., a settlement demand of $10,000 with $2,000 in submitted medical bills represents a 5:1 multiple), with final settlements as a multiple of medical costs (a $6,000 settlement demand with $2,000 in medical bills has a 3:1 ratio).

Chart 1 illustrates how medical costs dramatically affect the amount we are willing to settle for. It’d be hard to show any higher correlation. The higher the demand by a plaintiff attorney vis-à-vis the medical bills, the higher the settlement the attorney was able to negotiate. The plaintiff attorney very effectively “owns the anchor” by anchoring the overall value of the claim in the medical costs.

See also: Surprise Medical Bills: Just a Distraction

Why Medical Bills Influence

Medical bills have such an outsized impact on settlement values because they are, often, the only tangible item in discussions. Venue, pain and suffering, a claimant’s age, etc., aren’t tangible. By contrast, the dollar amounts shown in medical bills are easy to reference, and we naturally latch on to them.

Even when we seek to discredit the medical bills, we’re still referencing them, granting them relevance, even authority. They stubbornly remain the anchor.

The Fact-Based Fix

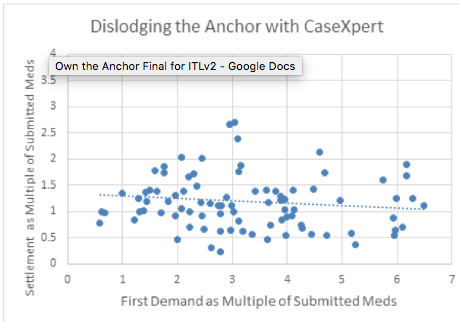

Chart 2

To understand how medical costs influence, or anchor, the settlement, we looked at the relationship of first demands as a multiple of submitted medical costs (e.g., a settlement demand of $10,000 with $2,000 in submitted medical bills represents a 5:1 multiple), with final settlements as a multiple of medical costs (a $6,000 settlement demand with $2,000 in medical bills has a 3:1 ratio).

Chart 1 illustrates how medical costs dramatically affect the amount we are willing to settle for. It’d be hard to show any higher correlation. The higher the demand by a plaintiff attorney vis-à-vis the medical bills, the higher the settlement the attorney was able to negotiate. The plaintiff attorney very effectively “owns the anchor” by anchoring the overall value of the claim in the medical costs.

See also: Surprise Medical Bills: Just a Distraction

Why Medical Bills Influence

Medical bills have such an outsized impact on settlement values because they are, often, the only tangible item in discussions. Venue, pain and suffering, a claimant’s age, etc., aren’t tangible. By contrast, the dollar amounts shown in medical bills are easy to reference, and we naturally latch on to them.

Even when we seek to discredit the medical bills, we’re still referencing them, granting them relevance, even authority. They stubbornly remain the anchor.

The Fact-Based Fix

Chart 2

Thankfully, facts are stubborn, too, and work very effectively to unseat anchors!

Plaintiff attorneys rely heavily (and successfully) on medical costs that they fail to examine to understand the underlying facts of their case. To exploit a claim’s facts, the approach demands a command and use of the facts of the injury and its treatment.

As Chart 2 illustrates, the same adjusters who produced the results in Chart 1 were subsequently able to “own the anchor” through negotiation grounded in facts. Our experience shows that using fact-based analyses dislodges the anchor of the submitted medical bills. In fact, the bills showed a negative correlation on the ultimate settlement accepted by the plaintiff attorneys.

The dispersion of results in Chart 2 shows that the tight relationship between submitted medical bills and settlements had ceased, with the anchor effectively displaced. This yields accurate settlement values grounded in facts. When arguing from facts, the adjuster calls the plaintiff attorney’s medical bill bluff and “owns the anchor.”

Set Sail

It's facts or nothing.

So, how do we stake our negotiations in facts? The answer rests in shifting a case from its “raw data,” like medical bill costs, to substantive arguments. And we don't mean bill review services, which focus on explanations of benefits and reductions in charges according to a fee schedule. Their use of obscure medical codes and rules, which aren't widely understood or capably explained in negotiations, means that bill reviews diminish their authority and can't help us to unseat the anchor.

Substantive arguments must be backed by evidence drawn directly from claim records, such as information from treatment notes, emergency room reports and observations from the medical world about how injuries are objectively documented and what justified medical care looks like. This approach will lower your ultimate settlement costs, with the wind in your sails.

See also: How to Cut Litigation Costs for Claims

For example, in a soft tissue injury case, plaintiff lawyers frequently assert that their client struggles with everyday activities. Rather than being drawn into this assertion, adjusters must undertake a thorough review of the claimant’s medical records (including treating physician, chiropractor and physical therapist notes) to determine if evidence is presented that demonstrates actual physical impairment. This includes examining observations of the claimant’s range of motion, strength and other functional deficits. If we aren’t prepared with this information, it is not difficult for a plaintiff attorney to use these assertions in conjunction with anchoring to drive the doubt in one’s mind that drives up the offers we’re willing to make. Except to the extent the lawyer’s claim of severe injury can be tied directly to evidence in the medical records, there is no basis for the adjuster’s evaluation to be influenced by the lawyer’s assertion. Where objective medical data indicates little to no impairment, claims of daily distress don’t hold water.

To dislodge the anchor cast by a plaintiff’s lawyer, adjusters must have organized medical records, a methodology (including the use of medical standards) to consistently review and interrogate the evidence from those records and the ability to produce a single, coherent assessment of the claim. We have found that the most effective use of evidence lies in the assessment of each component of a claim–-the pain and suffering of each injury, the legitimacy of claimed medical costs from each healthcare provider, the support for lost time from work. This is carried into negotiation, where an adjuster methodically presents his or her analysis of the claim and uses tactics for focusing the claim on facts. Training is a necessary element in this, but the dividends are significant.

Thankfully, facts are stubborn, too, and work very effectively to unseat anchors!

Plaintiff attorneys rely heavily (and successfully) on medical costs that they fail to examine to understand the underlying facts of their case. To exploit a claim’s facts, the approach demands a command and use of the facts of the injury and its treatment.

As Chart 2 illustrates, the same adjusters who produced the results in Chart 1 were subsequently able to “own the anchor” through negotiation grounded in facts. Our experience shows that using fact-based analyses dislodges the anchor of the submitted medical bills. In fact, the bills showed a negative correlation on the ultimate settlement accepted by the plaintiff attorneys.

The dispersion of results in Chart 2 shows that the tight relationship between submitted medical bills and settlements had ceased, with the anchor effectively displaced. This yields accurate settlement values grounded in facts. When arguing from facts, the adjuster calls the plaintiff attorney’s medical bill bluff and “owns the anchor.”

Set Sail

It's facts or nothing.

So, how do we stake our negotiations in facts? The answer rests in shifting a case from its “raw data,” like medical bill costs, to substantive arguments. And we don't mean bill review services, which focus on explanations of benefits and reductions in charges according to a fee schedule. Their use of obscure medical codes and rules, which aren't widely understood or capably explained in negotiations, means that bill reviews diminish their authority and can't help us to unseat the anchor.

Substantive arguments must be backed by evidence drawn directly from claim records, such as information from treatment notes, emergency room reports and observations from the medical world about how injuries are objectively documented and what justified medical care looks like. This approach will lower your ultimate settlement costs, with the wind in your sails.

See also: How to Cut Litigation Costs for Claims

For example, in a soft tissue injury case, plaintiff lawyers frequently assert that their client struggles with everyday activities. Rather than being drawn into this assertion, adjusters must undertake a thorough review of the claimant’s medical records (including treating physician, chiropractor and physical therapist notes) to determine if evidence is presented that demonstrates actual physical impairment. This includes examining observations of the claimant’s range of motion, strength and other functional deficits. If we aren’t prepared with this information, it is not difficult for a plaintiff attorney to use these assertions in conjunction with anchoring to drive the doubt in one’s mind that drives up the offers we’re willing to make. Except to the extent the lawyer’s claim of severe injury can be tied directly to evidence in the medical records, there is no basis for the adjuster’s evaluation to be influenced by the lawyer’s assertion. Where objective medical data indicates little to no impairment, claims of daily distress don’t hold water.

To dislodge the anchor cast by a plaintiff’s lawyer, adjusters must have organized medical records, a methodology (including the use of medical standards) to consistently review and interrogate the evidence from those records and the ability to produce a single, coherent assessment of the claim. We have found that the most effective use of evidence lies in the assessment of each component of a claim–-the pain and suffering of each injury, the legitimacy of claimed medical costs from each healthcare provider, the support for lost time from work. This is carried into negotiation, where an adjuster methodically presents his or her analysis of the claim and uses tactics for focusing the claim on facts. Training is a necessary element in this, but the dividends are significant.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Jim Kaiser is the CEO and founder of Casentric. Kaiser brings nearly 30 years of experience in the claims industry to Casentric.

We’re 10 to 15 years from the arrival of immensely powerful quantum computers; cryptography needs to be future-proofed starting now.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Byron Acohido is a business journalist who has been writing about cybersecurity and privacy since 2004, and currently blogs at LastWatchdog.com.

While many incentive programs are soon ignored, gamification makes desired actions and rewards part of the immediate sales environment.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Mark Herbert is president and CEO of Incentive Solutions (www.incentivesolutions.com). He has more than 30 years of experience overseeing business operations within the incentives industry.

In the wake of A.M. Best’s announcement that it will include a formal innovation assessment as part of its rating procedure for insurance companies, ITL Chief Innovation Officer Guy Fraker and I attended Best’s “Review and Preview” event in Scottsdale last week. Guy’s session was super well-attended, about twice as many folks as we expected. It’s rare in this type of event for no one in the audience to be looking at their phone or whispering to their neighbor, but everyone was attentive. With good reason: As became clear in all the sessions and in private conversations, the industry is at an inflection point.

You are either growing or dying, according to the adage. Nothing remains constant. If you are trying to maintain the status quo, you are setting simple survival as your "strategy," and mere survival is not a strategy. Given all the change that lies ahead for risk management and insurance businesses, you have to be aggressively innovating – or you are falling behind. You can’t just try to tread water while the world is changing rapidly around you..

As we noted in last week’s Six Things, A.M. Best has done the insurance world a huge favor by announcing a procedure for formally scoring insurance companies on their ability to innovate. Guy Kawasaki opened Best's event with a humorous run down of 10 insights on how to innovate (actually, 11; he threw in a bonus) and included this key: An innovative leader must bring people to the point where they “believe before they see.”

At ITL, we say you cannot do or build what you cannot imagine. But how do you imagine an unrecognizable future? That turns out to be hard for every insurance company. The successful companies will have the ability or willingness to believe in an innovation process before seeing results, because that process can keep you moving toward that future until it becomes possible to visualize it. That process doesn’t take ridiculous amounts of capital or gobs of people or a month of Sundays. We know. We’ve done it.

The call to innovate will divide insurance companies into three categories: those that drive toward growth and success; those that focus on the status quo and survival; and those that choose to sell.

Because technology is making our world safer all the time, the frequency of claims is falling, and our bet is that the severity will also decline. Roughly 90% of companies fight over 10% of gross written premium (GWP), and, in some circles, GWP is expected to drop as much as 20% over the next 10 years. The cost of customer acquisition and retention will remain high, and there will continue to be pressure on profitability as customers demand an experience like they’ve become used to thanks to Google, Amazon, Netflix, etc.

Many companies will want to take a wait-and-see approach, but time is not your friend. If you take a "slow follower" approach to innovation you will land by default in the hoping-for-survival category.

If you are in this survival category, either because of inaction, or a wait-and-see stance, you really are choosing to exit the game, at some point. How fast you exit will depend on a number of factors, but the time won’t be measured in decades, and you might have less control over the timing than you think. Brokers are looking to meet the needs of their customers to spur organic growth in their business, and, if a carrier has not innovated in ways that understand and meet those needs, the broker will recommend a different product from a more innovative company. Voila, you’re gone.

The last category comprises companies that do not have the will or capital to play the innovation game. For some, perhaps many, exit might be the best choice for stakeholders. But do not tarry. The markets will look for the best balance sheets. The longer you wait to hit the eject button, the more likely you are to find there are fewer buyers and lower valuations, if there are buyers at that point at all.

If you want to be in the category of companies that pursue innovation, get a favorable assessment from Best and thrive, ITL can help you to get a handle on whether you have the essential elements in place for innovation success. We have developed a free innovation assessment, which includes about 20 questions that will produce useful insights on the state of your innovation effort. At the end of the assessment, we will provide you with our findings and suggestions so you have a clearer picture of what your innovation future looks like. Click here to learn more and get started.

Best,

Wayne Allen

CEO

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Insurance Thought Leadership (ITL) delivers engaging, informative articles from our global network of thought leaders and decision makers. Their insights are transforming the insurance and risk management marketplace through knowledge sharing, big ideas on a wide variety of topics, and lessons learned through real-life applications of innovative technology.

We also connect our network of authors and readers in ways that help them uncover opportunities and that lead to innovation and strategic advantage.

The construction industry needs more video cameras to prevent accidents -- and shows the insurance industry a path to progress.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

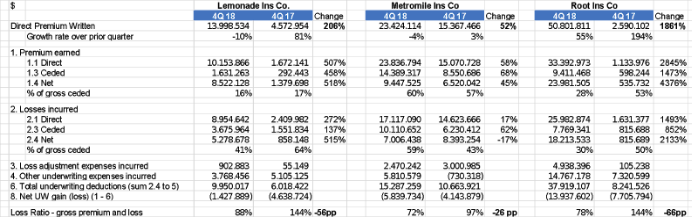

Quarterly growth for Lemonade, Metromile and Root was the slowest ever, but all three paid out in claims less than they collected in premium.

Skeptics point out that a quarter doesn’t mean much, that there’s a long way to go before reaching sustainability and that each additional point of loss gets harder to take out. True, but the increased focus this year on reducing losses and increasing prices is making a difference.

Here are the quarterly results:

Skeptics point out that a quarter doesn’t mean much, that there’s a long way to go before reaching sustainability and that each additional point of loss gets harder to take out. True, but the increased focus this year on reducing losses and increasing prices is making a difference.

Here are the quarterly results:

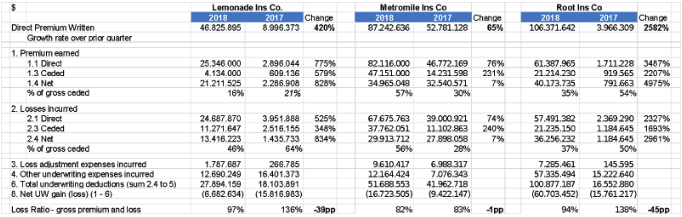

I think – as already mentioned in the previous articles - these companies have strong management teams who could ultimately create valuable businesses. This will take several years, but all three companies are well-funded, even if the combination of statutory capital injections and operating losses consumes tens of millions in capital each year. (The Uber/Lyft model of growing rapidly while also incurring large losses is doubly penalized in insurance because carriers have to maintain statutory capital that increases with premium.)

Here is a year-over-year comparison.

I think – as already mentioned in the previous articles - these companies have strong management teams who could ultimately create valuable businesses. This will take several years, but all three companies are well-funded, even if the combination of statutory capital injections and operating losses consumes tens of millions in capital each year. (The Uber/Lyft model of growing rapidly while also incurring large losses is doubly penalized in insurance because carriers have to maintain statutory capital that increases with premium.)

Here is a year-over-year comparison.

The three companies have sold in the last 12 months between $40 million and $110 million, less than some of the early 2017 enthusiastic forecasts that Lemonade (for example) would hit $90 million of premiums by the end of 2017. In auto, I pointed out at my IoT Insurance Observatory plenary sessions that the pay-as-you-drive telematics approach seems to attract only the niche of customers that rarely use cars – maybe a growing niche, but not a billion-dollar business (in premium at least).

See also: 9 Pitfalls to Avoid in Setting 2019 KPIs

Loss Ratios

Loss ratios have all been below 100%, which is a great improvement from the 2017 performances. The quarterly dynamics show a positive trend, but these loss ratio levels are far from the U.S. market average for home insurance (Lemonade) and auto insurance (Root and Metromile).

While loss ratio is a fundamental insurance number – claims divided by premiums -- I've been asked how to normalize/adjust the loss ratio of a fast-growing insurtech company.

Imagine a fast-growing insurer with the following annual figures:

The three companies have sold in the last 12 months between $40 million and $110 million, less than some of the early 2017 enthusiastic forecasts that Lemonade (for example) would hit $90 million of premiums by the end of 2017. In auto, I pointed out at my IoT Insurance Observatory plenary sessions that the pay-as-you-drive telematics approach seems to attract only the niche of customers that rarely use cars – maybe a growing niche, but not a billion-dollar business (in premium at least).

See also: 9 Pitfalls to Avoid in Setting 2019 KPIs

Loss Ratios

Loss ratios have all been below 100%, which is a great improvement from the 2017 performances. The quarterly dynamics show a positive trend, but these loss ratio levels are far from the U.S. market average for home insurance (Lemonade) and auto insurance (Root and Metromile).

While loss ratio is a fundamental insurance number – claims divided by premiums -- I've been asked how to normalize/adjust the loss ratio of a fast-growing insurtech company.

Imagine a fast-growing insurer with the following annual figures:

To measure efficiency, I prefer to use the two traditional components of the expense ratio:

To measure efficiency, I prefer to use the two traditional components of the expense ratio:

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Matteo Carbone is founder and director of the Connected Insurance Observatory and a global insurtech thought leader. He is an author and public speaker who is internationally recognized as an insurance industry strategist with a specialization in innovation.