Fertilizers and pesticides have increased crop yields for centuries, but they also create broader problems that increase pollution liability risks for farmers. Legislative and legal developments in the past several decades have led to unfortunate consequences: agricultural runoff is polluting rivers and oceans, and farmers and agribusinesses are exposed to environmental liability from everyday activities that were intended only to improve food production. Retail insurance agents can play an important role in advising agribusiness clients on loss prevention practices and working with wholesale specialists to develop tailored risk transfer solutions for agriculture risks.

Risks from agricultural runoff

Irrigation and precipitation cause runoff from fields and pastures, taking on chemicals and animal waste. Eventually, this runoff finds its way into streams and rivers, and drains into oceans. The runoff can cause algal blooms that spawn low-oxygen spots and disrupt marine ecosystems.

An analysis by North Carolina State University found a complex chain of effects from the addition of nitrogen and phosphorus – common ingredients in fertilizers. Published in the Biological Review, the analysis "combined the results of 184 studies drawn from 885 individual experiments around the globe that investigated the effects of adding nitrogen and phosphorus, the main components of fertilizer, in streams and rivers. While the analysis only included studies where scientists added nitrogen and phosphorus experimentally, nitrogen and phosphorus pollution can run off from farms into streams, lakes, and rivers – as well as from wastewater discharge. At high levels, fertilizer pollution can cause harmful algal blooms and can lead to fish kills."

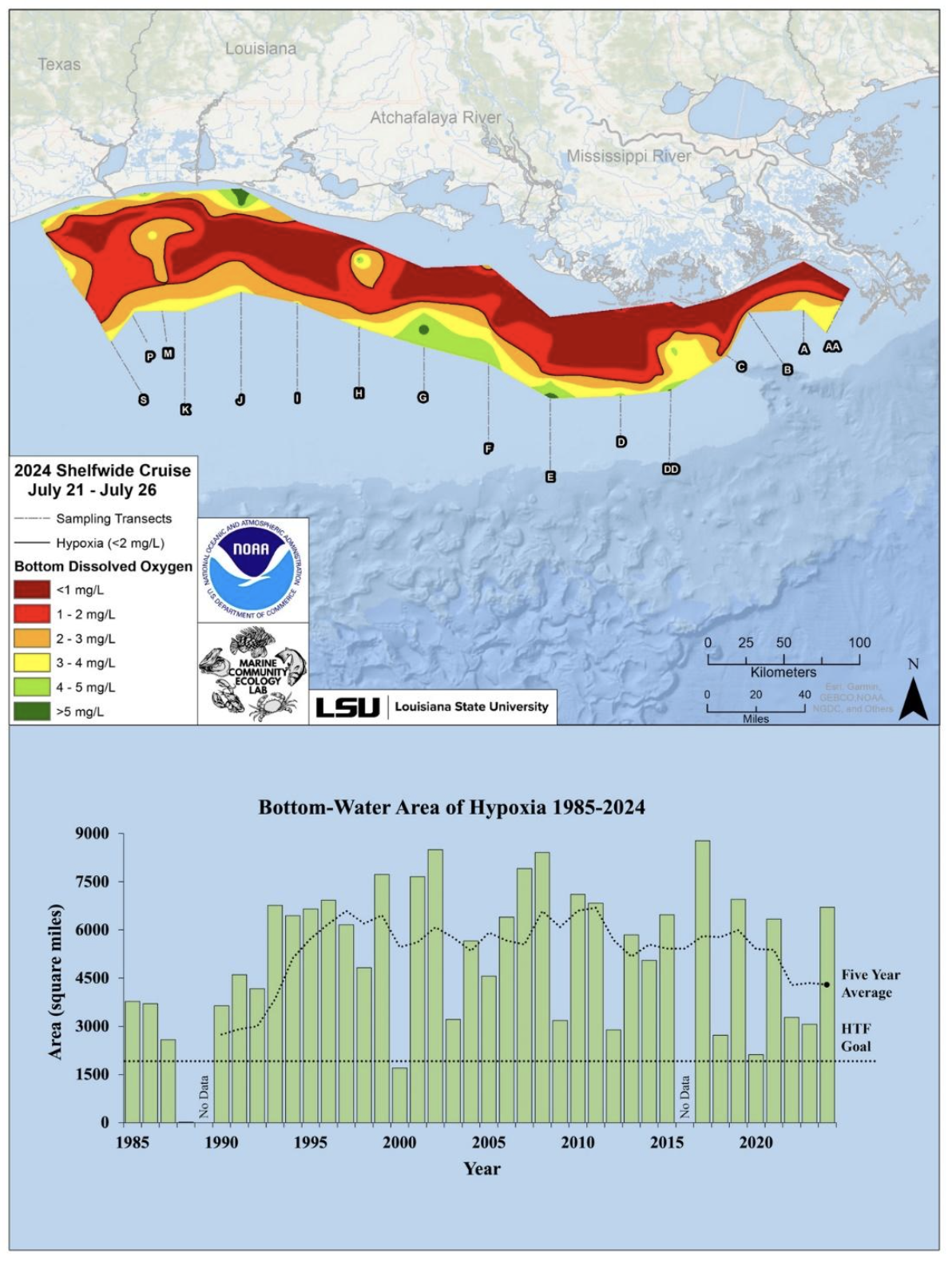

A prime example of these consequences is the "dead zone" in the Gulf of Mexico. The Science Education Resource Center at Carleton College says it "is primarily a result of runoff of nutrients from fertilizers and manure applied to agricultural land in the Mississippi River basin. Runoff from farms carries nutrients with the water as it drains to the Mississippi River, which ultimately flows to the Gulf of Mexico. If the number of nutrients reaching the Gulf of Mexico can be reduced, then the dead zone will begin to shrink."

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has studied the dead zone since 1985 and notes it varies in size. In Aug. 2024, NOAA estimated the Gulf of Mexico dead zone was more than 6,700 square miles – about the size of the state of New Jersey. Subsequently, the Hypoxia Task Force formed in 1997. Led by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and consisting of five federal agencies and 12 states, it has been working to implement policies and regulations to reduce the size of the zone.

Initiatives include:

- Better management of nutrient application can reduce nutrient runoff to streams.

- Planting of certain grasses, grains or clovers, called cover crops can recycle excess nutrients and reduce soil erosion, keeping nutrients out of surface waterways.

- Reducing how often fields are tilled reduces erosion and soil compaction, builds soil organic matter, and reduces runoff.

- Keeping animals and their waste out of streams, rivers, and lakes keep nitrogen and phosphorus out of the water and restores stream banks.

- Reducing nutrient loadings that drain from agricultural fields helps prevent degradation of the water in local streams and lakes.

Source: NOAA/Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium/Louisiana State University

Waste minimization and pollution risks

An analysis of United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization data shows that global meat production quintupled from 1961 to 2023. More than 360 million tons of meat are produced worldwide from various kinds of livestock. Managing the waste produced by the livestock required to fulfill global demand is an enormous challenge.

Since 1976, when the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) was enacted, the U.S. has sought to address the increasing volume of municipal and industrial waste. The 1984 passage of Hazardous and Solid Waste Amendments to RCRA "required phasing out land disposal of hazardous waste, corrective action for releases and waste minimization. Waste minimization refers to the use of source reduction and/or environmentally sound recycling methods prior to treating or disposing of hazardous wastes," according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

In recent years, additional legislation has extended to the agricultural efforts of farmlands that have the continuing potential to pollute and harm the very land on which they reside, in addition to the surrounding environment, groundwater and wildlife that share these spaces. The National Resources Defense Council defines agricultural pollution as "the contamination we release into the environment as a by-product of growing and raising livestock, food crops, animal feed, and biofuel crops."

Protecting farmers' right to farm, not pollute

State and federal court decisions in agricultural pollution cases have consistently found in favor of protecting the environment and adjacent lands. Courts have generally ruled the right to farm does not grant a right to pollute. Commonly, courts levying fines have issued findings of negligence, nuisance and trespassing related to the storage, hauling, treatment and disposal of waste of all kinds.

In 2014, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled that "manure applied to fertilize a field in the usual course of a farming business was transformed into a 'pollutant' when it seeped into adjoining neighbors' wells. As such, the Court ruled that a 'pollution exclusion' clause in the farmer's insurance policy eliminated the insurer's duty to defend in lawsuits seeking damage for the contaminated wells."

In the underlying case, the court noted the farmer used "manure from his dairy cows as fertilizer for his fields pursuant to a nutrient management plan prepared by a certified crop agronomist and approved by the Washington County Land and Water Conservation Division. Several months later, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources notified the farmer that the manure had polluted a local aquifer and contaminated neighboring water wells. The well owners demanded compensation, and the farmer sought coverage from his insurer under his farm owners' policy."

The insurer sought a declaratory judgment that it had no duty to defend or indemnify the farmer because "manure was a 'pollutant' subject to exclusion under the policy. The circuit court agreed with the insurer, finding that the pollution exclusion in the policy applied to exclude coverage for damage caused by the application of manure because 'a reasonable person in the position of the (farmer) would understand cow manure to be a waste,'" the state supreme court ruled.

Mitigating pollution liability

Farmers today face many difficult issues, from the effect of climate change and weather volatility to the continued urbanization of rural areas, to how to manage runoff and waste. What can farmers do with all the manure as their operation grows? How can farmers protect themselves from pollution laws even when they've done their best to alleviate the problem?

Fortunately, tailored pollution insurance solutions are available to retail agents and brokers to help curtail the potential effect of exposures and liability confronted by their clients, today's farmers and agricultural community. Some insurance options include:

- Sudden & Accidental (Time Element) Insurance. This typically covers sudden pollution incidents that happen on an insured's land. Incidents typically need to be found in about three days and reported to the insurance carrier within two weeks. It must begin and end in a certain timeframe and is meant to exclude true gradual pollution damage claims that occur accidentally over months or years. Gradual damage tends to be the most costly, hence why Sudden & Accidental pollution coverage for agriculture risks is so inexpensive.

- Pollution Legal Liability (PLL). This is a risk management tool for property owners that is typically designed to address premises pollution exposures. This claims-made coverage, in our experience, consistently manages the on- and off-site cleanup/remediation expenses; third-party bodily injury and property damage; and defense expenses associated with industries including the agricultural sector. However, because it is an expanded gradual coverage compared to sudden and accidental, it comes with a much higher price tag.

- Transportation Pollution Liability. This type of cargo pollution insurance generally covers pollution conditions caused during transportation, loading or unloading, and sometimes mis-delivery of this cargo including waste such as manure, or a product such as fertilizer.

- Non-Owned Disposal Site Liability (NODS) typically covers disposal of waste to a non-owned disposal facility. RCRA provides for joint and several liability for waste generators, meaning a farmer that uses a non-owned disposal facility can still be deemed a potentially responsible party for cleanup and remediation by the EPA. NODS coverage exists to indemnify insureds in this situation.

The key to helping protect the agricultural community from potential pollution conditions starts with the careful understanding of the client's workplace, practices and processes. A one-size-fits-all solution may not take into account the specifics involved in an insured's work and daily practices. Other solutions include the tailoring and blending of various policy forms to create an a la carte coverage form that is designed to help cover the specific pollution conditions of this unique marketplace.