We in the U.S. spend a lot on healthcare. Whether expressed as the cost per service, the cost per person or as a percentage of the gross domestic product, the high cost of healthcare is well documented. While solutions to this situation have been suggested for many years, the expensive reality continues.

Is it possible that unique characteristics of the American healthcare environment create special challenges? This article discusses several unique aspects.

Geographic Diversity

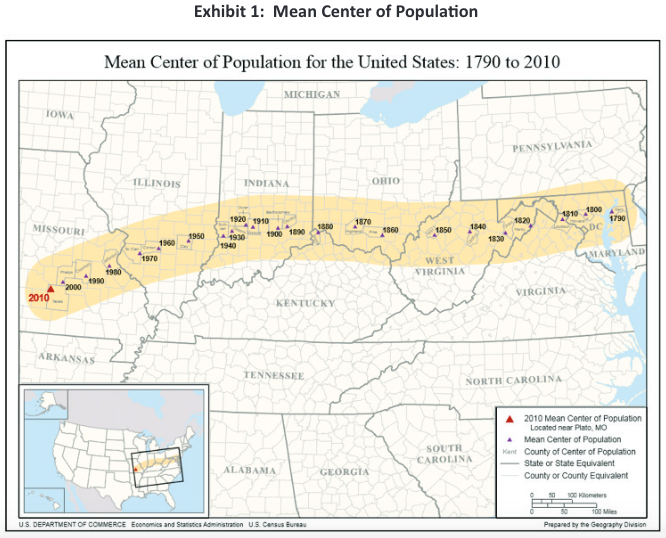

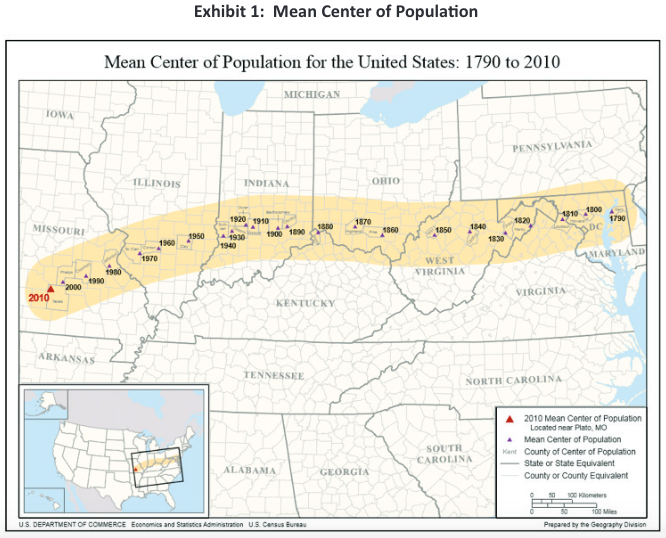

The U.S. is a diverse country with population centers scattered throughout the country. The mean center of population currently lies in Missouri.

As the inset map shows, this is east and south of the geographic center of the U.S. The major population centers in the eastern half of the country pull it east. The major population centers in the south pull it south. More than 10% of the population is in one major southwestern state, California. Major metropolitan areas can be found throughout the country: San Francisco and Los Angeles in the Southwest, Dallas and Houston in the south Midwest, Chicago in the upper Midwest, Boston and New York in the northeastern part of the country, Atlanta and Miami in the Southeast. Why is this important?

More than 90% of the Canadian population lives within 100 miles of the U.S. border. The oft-touted Canadian system serves a population that is concentrated in a thin band of land. In a concentrated environment, it is possible to have a more efficient allocation of resources. In the Canadian provinces with significant rural populations (e.g., Alberta and Saskatchewan) the provinces use regional health authorities to take responsibility.

See also: A Road Map for Health Insurance

American Definition of Quality

Quality is difficult to universally define. Many times people say, “I know it when I see it” or, more importantly “I know it when I don’t see it.” Over the past 15 to 20 years, quality has been objectively defined, to the point that it is consistently measured across health systems. One of the best definitions of quality is “providing the right service, at the right time, to the right patient as efficiently as possible.” The American definition of quality usually includes a high degree of access and a significant sense of urgency.

Other countries do not see waiting as a deterioration in quality. In fact, queuing, or waiting lines, are accepted. The American ideal is getting healthcare now, not tomorrow, not next week or next year. Most Americans see waiting as a reduction in quality. Health systems that require pre-authorization or approval of referrals are frequently viewed as substandard because those systems create barriers that patients have to work through. In countries with socialized healthcare systems, patients regularly have to wait. Much of this wait is associated with fiscal limits within the system restricting the available resources. In the U.S., the excess capacity in the system almost always provides an adequate supply of healthcare resources, so the required waiting time is very limited.

The waiting line is caused by either quotas or specific budgets for specific procedures, producing a rigid form of rationing. In the U.S., waiting occurs when the physician was booked or the schedule was full. This queue is not a budget-driven constraint.

The U.S. healthcare system is recognized as one of the highest-quality in the world (e.g., high cancer screening rates). Although the quality of care is generally quite high, some of the measured outcomes suggest that the U.S. health system is not advancing as much as would be hoped. One example is the efforts to eliminate breast cancer. Screening for breast cancer is higher than it has ever been, but so is the rate of breast cancer. Perhaps improved detection has identified more cases.

Freedom of Choice

Americans value freedom of choice; they like to make decisions for themselves. Americans value going where they want to get care, choosing who they want to provide that care, oftentimes deciding what care they want and getting it when they want to get it. This has resulted in broader networks offering more choices than needed. This has resulted in higher-than-necessary utilization of specific services, including new technology. The need for freedom of choice has limited the effectiveness of care management programs. Freedom of choice combined with limited cost sharing results in expensive healthcare. One unfortunate consequence is the negative opinion that develops regarding any administrative process that limits freedom of choice. Programs that focus on limiting medically unnecessary care are accused of disrupting the physician/patient relationship.

Healthcare Resource Planning

In most states, there is very limited overall resource planning. At various times, some states have implemented certificate of need programs for specific types of providers. But, for the most part, there are no formal limits to the number of providers or types of providers. In most urban markets, there is an oversupply of providers. Rural markets are often plagued with a shortage. Some markets are so desperate for providers that significant compensation is offered to lure them.

Why is this important? Healthcare tends to be a market that fails to respond to traditional supply and demand economics. In the general economy, the greater the supply, the lesser the demand and the lower the prices. In healthcare, the higher the supply, the greater the induced demand and the continuation of higher prices. Informal studies suggest that utilization levels positively correlate with supply.

One of the reasons for escalating costs is the continued oversupply of healthcare providers. One of the best examples of effective resource planning is the approach implemented by Kaiser Foundation Health Plan. Kaiser carefully plans the supply of professional services based on a long-established staffing model. As the associated membership grows, they move from a combination of “nearby owned facilities” and “rented facilities” to “owned facilities.” Kaiser carefully manages the strategic transition to a “wholly owned delivery system” and manages the resources based on membership growth. Kaiser avoids excess capacity and maintains a cost-effective delivery system.

Countries with socialized healthcare systems are much more involved with resource planning than the U.S. The competitive nature of healthcare in the U.S. is much more focused on capturing market share than defining appropriate resources for a region. Less effective resource planning drives up the cost of care.

Wide Variations in Efficiency

The efficiency of regional healthcare systems varies significantly from one geographic market to another. Delivery system care patterns have emerged based on local needs, regional care practices and the extent of provider involvement in the financing of care. Markets like Portland, OR, have developed extremely efficient in-patient care patterns with a larger portion of their healthcare dollar going to professional providers. Other markets have emerged at the same time with much less efficient patterns. In-patient utilization patterns vary by more than 35% to 45%. Analyses show no clinical rationale to support the observed variation. The U.S. is one of the few countries exhibiting this level of variation. Experts generally concur that much of this variation is caused by personal physician preference.

Tax-Sheltered Benefits

The current tax-sheltered employee benefit approach emerged during the post-WWII era where employers were seeking creative ways to attract, hire and keep employees. The tax law enabled employers to write off the cost of benefits and provide their employees a valuable tax-sheltered employee benefit. The tax law provides this favorable status only to employer-sponsored programs. Individual health insurance benefit programs do not enjoy this same tax advantage. Tax reform efforts have considered eliminating this difference. Self-funded employer-sponsored benefit programs, including those involving labor union negotiations (i.e., Taft -Hartley plans) are also tax-advantaged.

This is an important issue when discussing transitions to alternative systems. What role will employers play? What about programs negotiated by labor unions? How will we unravel the tax-advantaged funding of healthcare costs by the employer?

Diverse Insurance and Claims Administration

The employee health benefit marketplace has grown significantly with a large variety of organizations targeting the effective administration of such programs. Merger/acquisition activity has transformed the marketplace into a handful of major players and a large number of regional players. Third party administrators (TPAs) are active in the market supporting the self-funded and self-administered benefit programs. The federal government provides government-sponsored coverage for the elderly and disabled (Medicare) and for beneficiaries in lower socio-economic levels (Medicaid). Many of these programs outsource the administration and risk taking to the private sector. Healthcare administration in the U.S. includes a significant private sector involvement. There is little uniformity between different health plans. There are limited standards to streamline the process.

Public/Private Sector Cost Shift

The U.S. healthcare system incorporates a significant cost shift between the government-sponsored programs and the private sector programs. The private sector pays a much higher amount for identical services than the public sector. Within the private sector, each carrier/health plan is required to negotiate payment rates, which can vary substantially from one carrier to the next. The variability in reimbursement increases administrative costs for both the providers and the health plans or administrators.

See also: Healthcare Debate Misses Key Point

Hesitancy to Declare Healthcare a Human Rights Issue

In the U.S., there has been a hesitancy to declare healthcare a human rights issue. In Canada, the Canada Health Care Act defines five principles:

-

- Public Administration: All administration of provincial health insurance must be carried out by a public authority on a non-profit basis.

- Comprehensiveness: All necessary health services, including hospitals, physicians and surgical dentists, must be insured.

- Universality: All insured residents are entitled to the same level of healthcare.

- Portability: A resident who moves to a different province or territory is still entitled to coverage from the home province during a minimum waiting period. This also applies to residents who leave the country.

- Accessibility: All insured persons have reasonable access to healthcare facilities. In addition, all physicians, hospitals, etc., must be provided reasonable compensation for the services they provide.

A quick internet review will show considerable discussion defending both opinions: It is a right, or it isn’t a right. Dominant emerging thought focuses on what is called Triple Aim: a strong focus on quality and customer satisfaction, improving the population’s health status and reducing costs of care. They are admirable goals, but all require the definition or identification of a population. Who is the population? Is it everyone? Is it just the segment I am concerned about?

Recent healthcare reform efforts have focused on minimizing uninsured, which was a step toward universality. Ironically, the American’s demand for freedom of choice also includes freedom from being told that they must buy insurance and what kind of care they should pay for.

Summary

These nine issues provide an initial list of unique characteristics of the U.S. healthcare system. When working toward solutions to resolving the high cost of care, these issues must be considered. This is not an exhaustive list but does begin to highlight what makes American healthcare different.

As the inset map shows, this is east and south of the geographic center of the U.S. The major population centers in the eastern half of the country pull it east. The major population centers in the south pull it south. More than 10% of the population is in one major southwestern state, California. Major metropolitan areas can be found throughout the country: San Francisco and Los Angeles in the Southwest, Dallas and Houston in the south Midwest, Chicago in the upper Midwest, Boston and New York in the northeastern part of the country, Atlanta and Miami in the Southeast. Why is this important?

More than 90% of the Canadian population lives within 100 miles of the U.S. border. The oft-touted Canadian system serves a population that is concentrated in a thin band of land. In a concentrated environment, it is possible to have a more efficient allocation of resources. In the Canadian provinces with significant rural populations (e.g., Alberta and Saskatchewan) the provinces use regional health authorities to take responsibility.

See also: A Road Map for Health Insurance

American Definition of Quality

Quality is difficult to universally define. Many times people say, “I know it when I see it” or, more importantly “I know it when I don’t see it.” Over the past 15 to 20 years, quality has been objectively defined, to the point that it is consistently measured across health systems. One of the best definitions of quality is “providing the right service, at the right time, to the right patient as efficiently as possible.” The American definition of quality usually includes a high degree of access and a significant sense of urgency.

Other countries do not see waiting as a deterioration in quality. In fact, queuing, or waiting lines, are accepted. The American ideal is getting healthcare now, not tomorrow, not next week or next year. Most Americans see waiting as a reduction in quality. Health systems that require pre-authorization or approval of referrals are frequently viewed as substandard because those systems create barriers that patients have to work through. In countries with socialized healthcare systems, patients regularly have to wait. Much of this wait is associated with fiscal limits within the system restricting the available resources. In the U.S., the excess capacity in the system almost always provides an adequate supply of healthcare resources, so the required waiting time is very limited.

The waiting line is caused by either quotas or specific budgets for specific procedures, producing a rigid form of rationing. In the U.S., waiting occurs when the physician was booked or the schedule was full. This queue is not a budget-driven constraint.

The U.S. healthcare system is recognized as one of the highest-quality in the world (e.g., high cancer screening rates). Although the quality of care is generally quite high, some of the measured outcomes suggest that the U.S. health system is not advancing as much as would be hoped. One example is the efforts to eliminate breast cancer. Screening for breast cancer is higher than it has ever been, but so is the rate of breast cancer. Perhaps improved detection has identified more cases.

Freedom of Choice

Americans value freedom of choice; they like to make decisions for themselves. Americans value going where they want to get care, choosing who they want to provide that care, oftentimes deciding what care they want and getting it when they want to get it. This has resulted in broader networks offering more choices than needed. This has resulted in higher-than-necessary utilization of specific services, including new technology. The need for freedom of choice has limited the effectiveness of care management programs. Freedom of choice combined with limited cost sharing results in expensive healthcare. One unfortunate consequence is the negative opinion that develops regarding any administrative process that limits freedom of choice. Programs that focus on limiting medically unnecessary care are accused of disrupting the physician/patient relationship.

Healthcare Resource Planning

In most states, there is very limited overall resource planning. At various times, some states have implemented certificate of need programs for specific types of providers. But, for the most part, there are no formal limits to the number of providers or types of providers. In most urban markets, there is an oversupply of providers. Rural markets are often plagued with a shortage. Some markets are so desperate for providers that significant compensation is offered to lure them.

Why is this important? Healthcare tends to be a market that fails to respond to traditional supply and demand economics. In the general economy, the greater the supply, the lesser the demand and the lower the prices. In healthcare, the higher the supply, the greater the induced demand and the continuation of higher prices. Informal studies suggest that utilization levels positively correlate with supply.

One of the reasons for escalating costs is the continued oversupply of healthcare providers. One of the best examples of effective resource planning is the approach implemented by Kaiser Foundation Health Plan. Kaiser carefully plans the supply of professional services based on a long-established staffing model. As the associated membership grows, they move from a combination of “nearby owned facilities” and “rented facilities” to “owned facilities.” Kaiser carefully manages the strategic transition to a “wholly owned delivery system” and manages the resources based on membership growth. Kaiser avoids excess capacity and maintains a cost-effective delivery system.

Countries with socialized healthcare systems are much more involved with resource planning than the U.S. The competitive nature of healthcare in the U.S. is much more focused on capturing market share than defining appropriate resources for a region. Less effective resource planning drives up the cost of care.

Wide Variations in Efficiency

The efficiency of regional healthcare systems varies significantly from one geographic market to another. Delivery system care patterns have emerged based on local needs, regional care practices and the extent of provider involvement in the financing of care. Markets like Portland, OR, have developed extremely efficient in-patient care patterns with a larger portion of their healthcare dollar going to professional providers. Other markets have emerged at the same time with much less efficient patterns. In-patient utilization patterns vary by more than 35% to 45%. Analyses show no clinical rationale to support the observed variation. The U.S. is one of the few countries exhibiting this level of variation. Experts generally concur that much of this variation is caused by personal physician preference.

Tax-Sheltered Benefits

The current tax-sheltered employee benefit approach emerged during the post-WWII era where employers were seeking creative ways to attract, hire and keep employees. The tax law enabled employers to write off the cost of benefits and provide their employees a valuable tax-sheltered employee benefit. The tax law provides this favorable status only to employer-sponsored programs. Individual health insurance benefit programs do not enjoy this same tax advantage. Tax reform efforts have considered eliminating this difference. Self-funded employer-sponsored benefit programs, including those involving labor union negotiations (i.e., Taft -Hartley plans) are also tax-advantaged.

This is an important issue when discussing transitions to alternative systems. What role will employers play? What about programs negotiated by labor unions? How will we unravel the tax-advantaged funding of healthcare costs by the employer?

Diverse Insurance and Claims Administration

The employee health benefit marketplace has grown significantly with a large variety of organizations targeting the effective administration of such programs. Merger/acquisition activity has transformed the marketplace into a handful of major players and a large number of regional players. Third party administrators (TPAs) are active in the market supporting the self-funded and self-administered benefit programs. The federal government provides government-sponsored coverage for the elderly and disabled (Medicare) and for beneficiaries in lower socio-economic levels (Medicaid). Many of these programs outsource the administration and risk taking to the private sector. Healthcare administration in the U.S. includes a significant private sector involvement. There is little uniformity between different health plans. There are limited standards to streamline the process.

Public/Private Sector Cost Shift

The U.S. healthcare system incorporates a significant cost shift between the government-sponsored programs and the private sector programs. The private sector pays a much higher amount for identical services than the public sector. Within the private sector, each carrier/health plan is required to negotiate payment rates, which can vary substantially from one carrier to the next. The variability in reimbursement increases administrative costs for both the providers and the health plans or administrators.

See also: Healthcare Debate Misses Key Point

Hesitancy to Declare Healthcare a Human Rights Issue

In the U.S., there has been a hesitancy to declare healthcare a human rights issue. In Canada, the Canada Health Care Act defines five principles:

As the inset map shows, this is east and south of the geographic center of the U.S. The major population centers in the eastern half of the country pull it east. The major population centers in the south pull it south. More than 10% of the population is in one major southwestern state, California. Major metropolitan areas can be found throughout the country: San Francisco and Los Angeles in the Southwest, Dallas and Houston in the south Midwest, Chicago in the upper Midwest, Boston and New York in the northeastern part of the country, Atlanta and Miami in the Southeast. Why is this important?

More than 90% of the Canadian population lives within 100 miles of the U.S. border. The oft-touted Canadian system serves a population that is concentrated in a thin band of land. In a concentrated environment, it is possible to have a more efficient allocation of resources. In the Canadian provinces with significant rural populations (e.g., Alberta and Saskatchewan) the provinces use regional health authorities to take responsibility.

See also: A Road Map for Health Insurance

American Definition of Quality

Quality is difficult to universally define. Many times people say, “I know it when I see it” or, more importantly “I know it when I don’t see it.” Over the past 15 to 20 years, quality has been objectively defined, to the point that it is consistently measured across health systems. One of the best definitions of quality is “providing the right service, at the right time, to the right patient as efficiently as possible.” The American definition of quality usually includes a high degree of access and a significant sense of urgency.

Other countries do not see waiting as a deterioration in quality. In fact, queuing, or waiting lines, are accepted. The American ideal is getting healthcare now, not tomorrow, not next week or next year. Most Americans see waiting as a reduction in quality. Health systems that require pre-authorization or approval of referrals are frequently viewed as substandard because those systems create barriers that patients have to work through. In countries with socialized healthcare systems, patients regularly have to wait. Much of this wait is associated with fiscal limits within the system restricting the available resources. In the U.S., the excess capacity in the system almost always provides an adequate supply of healthcare resources, so the required waiting time is very limited.

The waiting line is caused by either quotas or specific budgets for specific procedures, producing a rigid form of rationing. In the U.S., waiting occurs when the physician was booked or the schedule was full. This queue is not a budget-driven constraint.

The U.S. healthcare system is recognized as one of the highest-quality in the world (e.g., high cancer screening rates). Although the quality of care is generally quite high, some of the measured outcomes suggest that the U.S. health system is not advancing as much as would be hoped. One example is the efforts to eliminate breast cancer. Screening for breast cancer is higher than it has ever been, but so is the rate of breast cancer. Perhaps improved detection has identified more cases.

Freedom of Choice

Americans value freedom of choice; they like to make decisions for themselves. Americans value going where they want to get care, choosing who they want to provide that care, oftentimes deciding what care they want and getting it when they want to get it. This has resulted in broader networks offering more choices than needed. This has resulted in higher-than-necessary utilization of specific services, including new technology. The need for freedom of choice has limited the effectiveness of care management programs. Freedom of choice combined with limited cost sharing results in expensive healthcare. One unfortunate consequence is the negative opinion that develops regarding any administrative process that limits freedom of choice. Programs that focus on limiting medically unnecessary care are accused of disrupting the physician/patient relationship.

Healthcare Resource Planning

In most states, there is very limited overall resource planning. At various times, some states have implemented certificate of need programs for specific types of providers. But, for the most part, there are no formal limits to the number of providers or types of providers. In most urban markets, there is an oversupply of providers. Rural markets are often plagued with a shortage. Some markets are so desperate for providers that significant compensation is offered to lure them.

Why is this important? Healthcare tends to be a market that fails to respond to traditional supply and demand economics. In the general economy, the greater the supply, the lesser the demand and the lower the prices. In healthcare, the higher the supply, the greater the induced demand and the continuation of higher prices. Informal studies suggest that utilization levels positively correlate with supply.

One of the reasons for escalating costs is the continued oversupply of healthcare providers. One of the best examples of effective resource planning is the approach implemented by Kaiser Foundation Health Plan. Kaiser carefully plans the supply of professional services based on a long-established staffing model. As the associated membership grows, they move from a combination of “nearby owned facilities” and “rented facilities” to “owned facilities.” Kaiser carefully manages the strategic transition to a “wholly owned delivery system” and manages the resources based on membership growth. Kaiser avoids excess capacity and maintains a cost-effective delivery system.

Countries with socialized healthcare systems are much more involved with resource planning than the U.S. The competitive nature of healthcare in the U.S. is much more focused on capturing market share than defining appropriate resources for a region. Less effective resource planning drives up the cost of care.

Wide Variations in Efficiency

The efficiency of regional healthcare systems varies significantly from one geographic market to another. Delivery system care patterns have emerged based on local needs, regional care practices and the extent of provider involvement in the financing of care. Markets like Portland, OR, have developed extremely efficient in-patient care patterns with a larger portion of their healthcare dollar going to professional providers. Other markets have emerged at the same time with much less efficient patterns. In-patient utilization patterns vary by more than 35% to 45%. Analyses show no clinical rationale to support the observed variation. The U.S. is one of the few countries exhibiting this level of variation. Experts generally concur that much of this variation is caused by personal physician preference.

Tax-Sheltered Benefits

The current tax-sheltered employee benefit approach emerged during the post-WWII era where employers were seeking creative ways to attract, hire and keep employees. The tax law enabled employers to write off the cost of benefits and provide their employees a valuable tax-sheltered employee benefit. The tax law provides this favorable status only to employer-sponsored programs. Individual health insurance benefit programs do not enjoy this same tax advantage. Tax reform efforts have considered eliminating this difference. Self-funded employer-sponsored benefit programs, including those involving labor union negotiations (i.e., Taft -Hartley plans) are also tax-advantaged.

This is an important issue when discussing transitions to alternative systems. What role will employers play? What about programs negotiated by labor unions? How will we unravel the tax-advantaged funding of healthcare costs by the employer?

Diverse Insurance and Claims Administration

The employee health benefit marketplace has grown significantly with a large variety of organizations targeting the effective administration of such programs. Merger/acquisition activity has transformed the marketplace into a handful of major players and a large number of regional players. Third party administrators (TPAs) are active in the market supporting the self-funded and self-administered benefit programs. The federal government provides government-sponsored coverage for the elderly and disabled (Medicare) and for beneficiaries in lower socio-economic levels (Medicaid). Many of these programs outsource the administration and risk taking to the private sector. Healthcare administration in the U.S. includes a significant private sector involvement. There is little uniformity between different health plans. There are limited standards to streamline the process.

Public/Private Sector Cost Shift

The U.S. healthcare system incorporates a significant cost shift between the government-sponsored programs and the private sector programs. The private sector pays a much higher amount for identical services than the public sector. Within the private sector, each carrier/health plan is required to negotiate payment rates, which can vary substantially from one carrier to the next. The variability in reimbursement increases administrative costs for both the providers and the health plans or administrators.

See also: Healthcare Debate Misses Key Point

Hesitancy to Declare Healthcare a Human Rights Issue

In the U.S., there has been a hesitancy to declare healthcare a human rights issue. In Canada, the Canada Health Care Act defines five principles: