The first time I really thought about wiring the world with sensors came in 2007, when I was speaking at a boutique conference right after -- to drop a name -- Mike Mullen. Mullen was at that point the chief naval officer and a few months later was named chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

He stayed for the full three days of the conference, and I kept bumping into him at the coffee bar, where I found him charming in a geeky, four-star-admiral kind of way. I've always appreciated it when famous/important people can laugh at themselves, and he told me he'd been surprised to learn that one of the perks of becoming chief naval officer was that then-President George W. Bush invited him to the National Prayer Breakfast, where Bono would speak.

"Bono?" Mullen said he asked himself. "The singer who was married to Cher? Didn't he die in a skiing accident 10 years ago?"

Fortunately, Mullen wasn't there to talk music or pop culture. He wanted to lay out an idea he called the "1,000-ship navy." The U.S. has some 250 ships in active service at any given time, so he wasn't just describing a U.S. initiative. He was talking about finding a way for many of the world's navies to coordinate on issues of common interest and patrol the oceans in ways that no single navy could manage. He especially had his eye on the Somali pirates who were such a scourge at the time -- and a coalition of more than a dozen nations did, in fact, cooperate and greatly reduce piracy by 2010.

With those conversations as a starting point, I've followed a variety of attempts since then to wire the world with eyes and ears and all sorts of other sensors, some on the ground, some in the air, many in space. And we're making great progress.

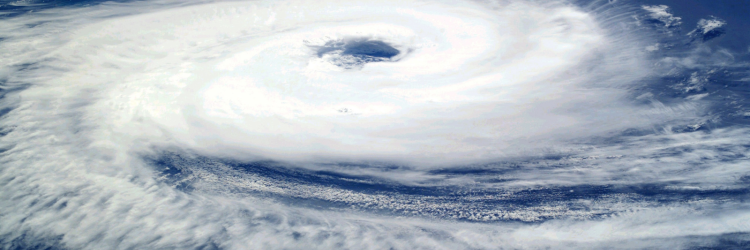

Advances in data collection and in the supercomputers that make sense of all that data are helping us predict the paths and intensity of hurricanes and other types of extreme weather, which means governments and insurers can help protect people and their possessions. Advances will also help governments and insurers reduce fraud.

Way back in 1987, when I was young and invincible and spent 27 days sailing across the Atlantic in a 42-foot boat as a crew member in a race, we could only get a satellite fix on our position six times a day. We got so little weather information that we stumbled into 12 days of nearly constant storms and a stretch of 70-foot waves that caused such mayhem on the QEII that there were national news stories.

(Did I mention that I'd never sailed before? Or that I was at the helm in the middle of the darkest night imaginable for some of the worst of the storms, with the rain blowing so hard in my face that I couldn't have seen anything anyway? Digression.... I know....)

Today, my particular form of recklessness would barely be possible. There are so many satellites up there that they're in danger of running into each other. They will tell you precisely where you are at any moment, even in the middle of an ocean. They will also give you such good information on the weather that you won't, just to pick a situation at random, head straight toward the middle of a massive low-pressure system and spend 12 days getting beaten silly by storms in a little boat, 1,500 miles from the nearest land.

The processing of the data from all those satellites has maybe moved even faster than all the launches. The MIT Technology Review reports that, because of advancements in supercomputers, "Average errors in hurricane path predictions dropped from about 100 miles in 2005 to about 65 miles in 2020. The difference might seem small when storms can be hundreds of miles wide, but when it comes to predicting where the worst effects from a hurricane will hit, 'every little wiggle matters,'" according to the head of the Hurricane Specialist Unit at the National Hurricane Center. And two new supercomputers delivered to the National Weather Service at the end of 2021 should continue the progress.

The article adds: "Understanding and predicting hurricanes’ intensity has been more challenging than predicting their paths, since the strength of a hurricane is driven by more local factors, like wind speed and temperature at the center of a storm. Still, intensity predictions have also started to improve in the past decade. Errors in the intensity forecast within 48 hours decreased by 20% to 30% between 2005 and 2020."

A more recent MIT Technology Review article says AI is even getting better at predicting the intensity of storms because it is being trained on the basics of the physics that determines intensity, not just on historical storm data. That sort of improvement might have, for instance, mitigated the disaster in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, in April, when what was expected to be a routine thunderstorm lasted hours and dumped some 25 inches of rain.

Getting better at predicting paths and intensity will at least allow for enough warning that residents can evacuate ahead of a major storm and will save lives. The improvements may eventually also allow for people to do a much better job of securing their homes before they leave.

The profusion of satellites is also making it far easier to track shipping, helping governments and insurers spot fraud. Some shippers have figured out how to turn off transponders that broadcast where their vessels are and use sophisticated technology to "spoof" their locations so they can appear to be in international waters while actually picking up Russian oil or delivering cargo to a pariah nation such as North Korea. But those ships can no longer hide from satellites. So governments can know when rogue shippers and their national sponsors are violating sanctions, and insurers can know when shippers are violating the terms of their policies.

The world is becoming so wired that military analysts are using earthquake sensors (underground, not in space, in this case) to track where Russian missiles and bombs are striking in Ukraine. As a result, the analysts not only have pictures that document the damage from the attacks but can show exactly when they occurred, based on the readings from dozens of earthquake sensors nearby -- information that could be useful in any war crimes trials.

We have a long way to go before the world is truly wired, but we've come a long way, with great benefits for governments, citizens and insurers -- and any 20-something kid reckless enough to decide it'd be cool to sail across an ocean.

Cheers,

Paul