This is Paper 3 of a series of five on risk appetite and associated questions. The author believes that enterprise risk management (ERM) will remain locked in organizational silos until boards comprehend the links between risk and strategy. This is achieved either through painful crises or through the less expensive development of a risk appetite framework (RAF). Understanding of risk appetite is very much a work in progress for many organizations, but RAF development and approval can lead boards to demand action from executives.

Paper 1, the shortest paper, makes a number of general observations based on experience with a wide variety of companies.

Paper 2 describes the risk landscape, measurable and unmeasurable uncertainties and the evolution of risk management. This paper, Paper 3, answers questions relating to the need for risk appetite frameworks and describes in some detail the relationship between risk appetite frameworks and strategy. Paper 4 answers further questions on risk appetite and goes into some detail on the questions of risk culture and risk maturity. Paper 5 describes the characteristics of a risk appetite statement and provides a detailed summary of how to operationalize the links between risk and strategy.

Paper 3: Should all organizations have a risk appetite framework?

The relationship between risk and strategy is a function or neither risk management nor strategic management. Rather, it is simply good management in an uncertain world, where business models are:

- Increasingly driven to be available on a 24/7 global footprint,

- Online using telecom networks,

- Becoming more dependent on third-party service providers,

- Becoming more connected within larger financial, supply chain and energy supply chains.

It is our view that the term "risk management" will, within the 2010 decade, become supplanted by the term "resilience management" and that the latter term will become an integral part of risk culture in organizations that are trading internationally or vulnerable to international supply chains.

Maintaining a risk appetite framework will thus, before the end of this decade, be a matter of necessity, and not a matter of choice. The driver in this regard will be the pace of change. Look at the pictures above, both at a papal blessing, and you see what a difference less than a decade years can make.

What is leading organizations to put formal risk appetite frameworks in place?

Greater investor and regulatory focus, combined with a recognition that risk practices are becoming increasingly professional, has caused organizations to change attitude toward risk from a broadly negative stance to a more positive and engaged approach.

We note a global scarcity of skilled chief risk officers and unwillingness by organizations to commit resources in the current economic climate. Nevertheless, enlightened organizations are gaining appreciation of the links between risk and strategy and in turn toward putting in place the necessary resources and supports to provide greater risk professionalism.

How are risk appetite and strategy related?

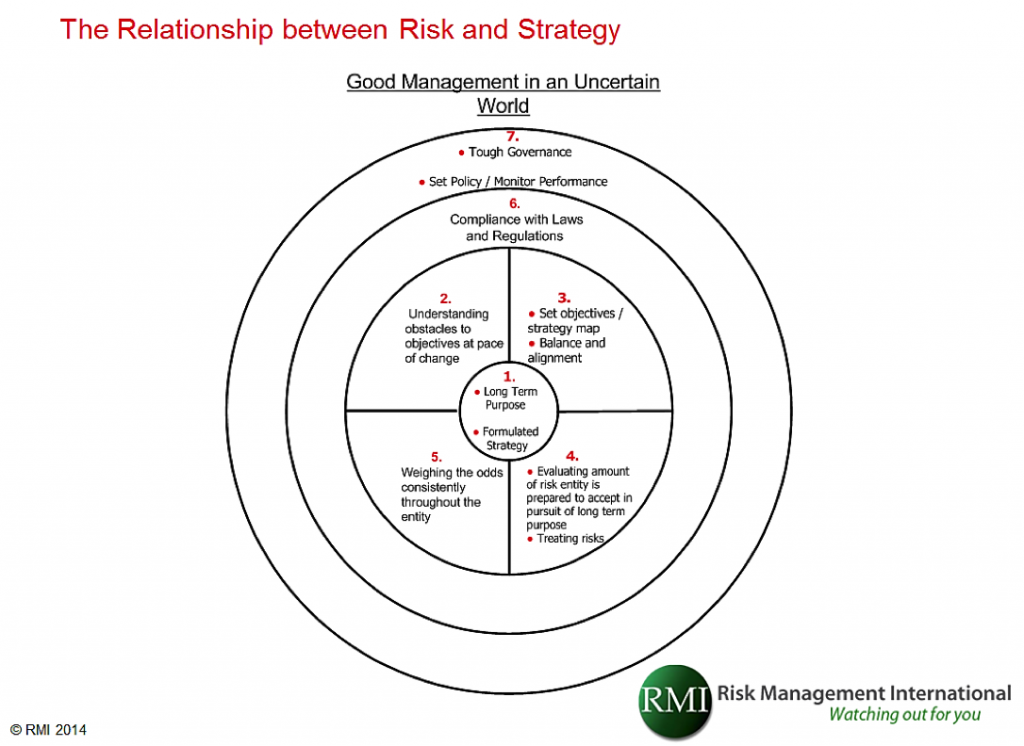

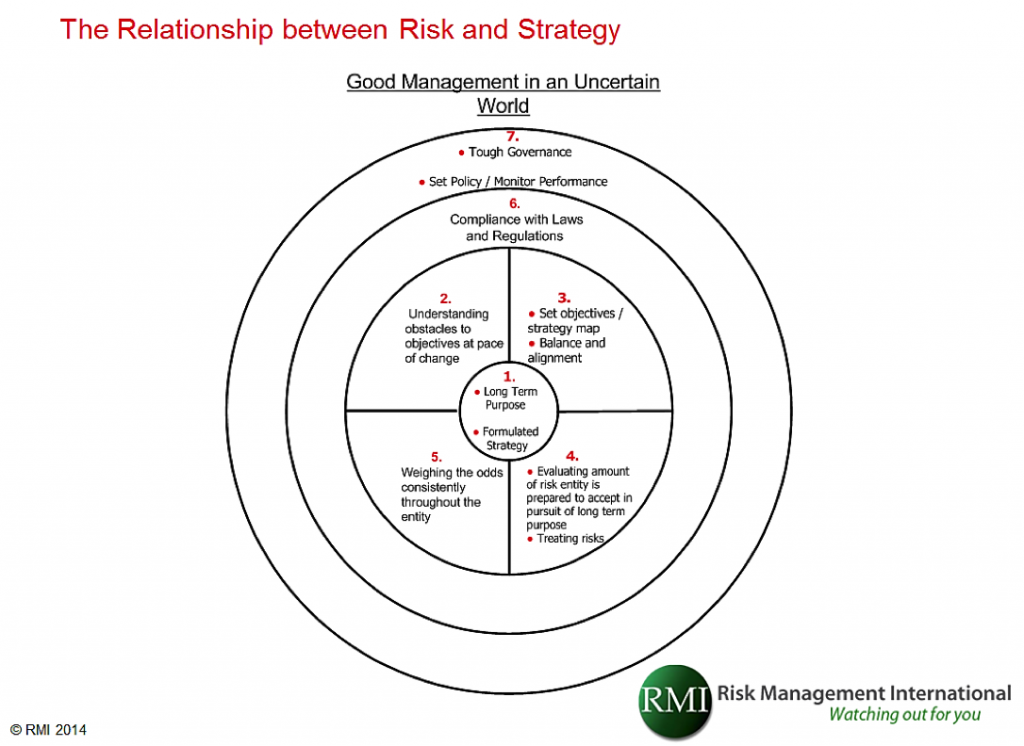

The diagram below describes the relationship.

Figure 2: RMI’s 7 elements approach to aligning strategy and risk

Earlier in these papers, we described board risk assurance as assurance that strategy, objectives and execution are aligned.

We further explained that alignment is achieved by operationalizing the links between risk and strategy. This is done by integrating each of the seven numbered elements described in the diagram above as follows:

1. Reaching a determination as to long-term purpose and formulating those strategic initiatives and objectives that are required to achieve it[1],

2. Understanding obstacles to the achievement of objectives: This needs to be understood

practically in terms of a motor journey from say Dublin to Cork or Berlin to Paris.

Before the journey, people need to understand, and manage, what can stop them, slow them down or distract them on the journey. Once people understand risk management in these simple and practical terms, they understand that risk management is more about achieving objectives (getting from point A to point B) than compliance with regulations. It is about improving performance on the journey.

What people? In the simplest of terms, they are the owners of the car (shareholders represented by the board), the driver (CEO and executives) and passengers (primary stakeholders, i.e. customers, employees, investors, suppliers and secondary stakeholders and others with a legitimate interest in the business).

3. Setting objectives and getting balance and alignment (Note: strategy maps, e.g. Balanced Scorecard):

This is done in risk management terms by:

a. Strengthening the strategic planning process; for example:

i. Increasing rigor, formality and consistency in the strategic planning office (SPO), which derives its authority from the board and the CEO's office,

ii. Aligning strategy, risk and audit board subcommittees (through cross-representation) in a manner that largely mirrors the conventional three lines of defense model

[2] and reflects the requirement to strengthen board risk oversight, reporting and monitoring

[3],

iii. Embedding risk management competence within the SPO

[4],

iv. Explicitly articulating corporate and organizational objectives,

v. Testing the alignment of group, corporate and organizational objectives through development and review of risk appetite statements.

b. Establishing an effective risk appetite framework, which includes:

i. Statement of purpose and values of the organization,

ii. Explicitly stated board risk assurance requirements; factors to consider would include:

- Mapping objectives to a risk appetite continuum,

- Qualitatively expressed risk appetite statements,

- Quantitatively expressed risk criteria related to both risk tolerance and risk limits.

c. Understanding and improving the organizational level of risk maturity

Risk maturity is outside the scope of this paper; however, discussion on the topic would be welcomed by RMI. RMI has developed a five-level RMI Risk Maturity Index, which provides a road map to risk optimization. The index scores risk maturity capability requirements, etc. In summary, it describes:

- Level 5: "Value-Driven" -- Optimizing value through aligning risk and strategy with corporate objectives,

- Level 4: "Managed" -- Gaining value through aligning risk and strategy in pursuit of corporate objectives,

- Level 3: "Insight" -- Gaining insights into how to better align risk and strategy in pursuit of corporate objectives,

- Level 2: "Awareness" -- Developing awareness into how to align risk and strategy in pursuit of corporate objectives,

- Level 1: "Basic" -- Seeking awareness of the links of risk and strategy in pursuit of corporate objectives.

d. Building resilience:

i. Ensuring that the SPO engages in systematic risk horizon scanning as well as:

1. Understanding near misses and escalation reports in the organization and externally,

2. Monitoring performance of risk treatments

[5],

3. Proofs and tests of the quality of decision making, and decision making processes, through simulated threat and opportunity crisis

[6] scenario(s) exercises,

ii. Anticipating Emerging Risks

[7].

4. Evaluating the amount of risk the organization is prepared to accept in pursuit of the long-term statement of purpose; and then deciding how to treat risks:

Just as implementation is critical to performance

[8], risk treatment is at the cutting edge of risk management and managing risks!

Disappointingly, however, very many organizations commit disproportionate resources to risk assessment with inadequate attention paid to what really matters; that is,

treating risks. In essence, very many organizations concentrate on the P in the PDCA (plan, do, check, act) cycle, with not enough attention paid to doing, checking and acting on continuous improvement requirements.

This is pretty much in evidence in a review of many of the risk registers we have examined on behalf of clients. The majority of the surface area/content of the report (sadly, and sometimes tragically, an Excel, Word or Power Point document, as distinct from a credible database solution

[9]) is given to risk assessment.

In our experience, often, precious little detail is given to:

- Who, specifically is responsible for individual risk treatments,

- Change management and resource requirements supporting risk treatments,

- The project/risk treatment key performance indicators (KPIs), milestones and gateways,

- The expected residual effect of risk treatments on likelihood and impact,

- The role of management in reviewing performance against KPIs, milestones and gateways.

Risk treatment reports, which are presented to the level of detail described above and which are evaluated by the SPO in a manner that provides a feedback loop to the performance of objectives, become leading indicators of the future state of health of objectives.

5. Weighing the odds consistently throughout the organization: This is the function of the chief risk officer (CRO), a most important role within the organization, and risk committee.

The ability of the CRO and risk committee to efficiently and effectively perform this function is directly proportional to the efficacy of the assurances delivered as described above.

Typical weaknesses and challenges that can occur include:

1. Frequency of changes required to risk criteria (tolerances and limits) in early stage (risk) maturity organizations as a consequence of:

- Pace of change internally and externally in the organization,

Identification of emerging and external risks hitherto not understood.

2. Inability to undertake real time dynamic tests of risk aggregations:

- Around discrete objectives,

- Across risk categories.

The weaknesses and challenges described above often result in:

1. Meetings where questions asked can only be answered in terms of:

i. This is the historic "point in time" information we have prepared.

ii. We will need to revert with answers to your query in X days.

2. Risk aggregation tests not being run and emerging/known unknown risks not being identified until there is an occurrence.

6. Compliance with laws and regulations: Organizations are established to achieve superior returns, with limited liability to risk takers. However, they are expected to do so having full regard for all legal requirements.

Clearly, it is axiomatic to assume the lawful intent of a company’s original promoters, and thereafter its directors and the executive. To this extent, compliance is an operational imperative and a sunken cost.

Compliance alone does not drive value, but without it value cannot be created.

It would seem inappropriate to place compliance at the center of board agenda, just as it would be a mistake to place compliance at the center of the diagram above, which describes the relationship between risk and strategy.

However, compliance is a mission-critical element within the risk/strategy governance framework.

7. Tough governance, setting policy and monitoring performance: In the context of the relationship between risk and strategy,

tough governance means risk culture.

"Risk culture" is a term describing the values, belief, knowledge and understanding about risk shared by a group of people with a common purpose, in particular the employees of an organization or of teams or groups within an organization. This applies whether the organizations are private companies, public bodies or not-for profits, wherever they are in the world.

[10].

Risk culture, as an aspect of culture, can be practically described thus:

Culture: The way we do things around here!

Risk culture: The freedom we have to challenge around here!

Risk culture is capable of being demonstrably and credibly evidenced by:

1. Board and executive messaging

[11] on threats and risks to operations and jobs when people fail to act/report when they:

i. Identify a smarter way of completing a task, achieving an objective,

ii. See a threat or risk to the organization.

2. Escalation reports and their treatment by the executive and management,

3. Near misses reported and averted.

References

[1] Strategy formulation is not part of the development of risk appetite frameworks; however, each is intrinsic to, and informs, the other.

[2] IIA Position Paper: The Three Lines of Defense in Effective Risk Management and Internal Control, January 2013

[3] Board Risk Oversight, A Progress Report: Where Boards of Directors Currently Stand in Executing Their Risk Oversight Responsibilities (Protiviti Report commissioned by COSO (Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Threadway Commission))

[4] NOTE: Risk Management and the Strategy Execution System by Robert S. Kaplan, which advances a method for aligning enterprise risk management with strategy through the Balanced Scorecard

[5] Effective reporting and monitoring of risk treatments delivers the twin benefits of 1) monitoring risk performance, and 2) establishing leading indicators on the future state of health of objectives

[6] Crisis is defined as: An inherently abnormal, unstable and complex situation that represents a threat to the strategic objectives, reputation or existence of an organization: PAS 200:2011 Crisis Management – Guidance and Good Practice, UK Cabinet Office in partnership with the British Standards Institute

[7] Reference Kaplan, Mikes Level 1 Global Enterprise Risks,

[8] McKinsey, August 2014, Why Implementation Matters: Good implementers—defined as companies where respondents reported top-quartile scores for their implementation capabilities—are 4.7 times more likely than bottom-quartile companies to say they ran successful change efforts over the past five years. Respondents at the good implementers also score their companies around 30% higher on a series of financial performance indexes. Perhaps most important, the good-implementer respondents say their companies sustained twice the value from their prioritized opportunities two years after the change efforts ended, compared with those at poor implementers

[9] Functionally designed and specified to meet the ISO 31000 series

[10] Institute of Risk Management (IRM) , Risk Culture, Under the Microscope: Guidance for Boards

[11] Speak up/Stand up/Ethics Line/Whistleblower Lines etc.

Sir James Dyson with his Dyson Vacuum

If the term had existed, the board of Dyson’s company at that time might have labeled Dyson’s effort an ill-conceived “red ocean” strategy. It rejected his request for funding to produce the vacuum -- even though Dyson owned a third of the company. Dyson was told:

Sir James Dyson with his Dyson Vacuum

If the term had existed, the board of Dyson’s company at that time might have labeled Dyson’s effort an ill-conceived “red ocean” strategy. It rejected his request for funding to produce the vacuum -- even though Dyson owned a third of the company. Dyson was told: