Building Blocks for Risk Leaders (Part 2)

Risk leaders increasingly need broader experience and capabilities and should hone their skills outside their organizations.

Risk leaders increasingly need broader experience and capabilities and should hone their skills outside their organizations.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Christopher E. Mandel is senior vice president of strategic solutions for Sedgwick and director of the Sedgwick Institute. He pioneered the development of integrated risk management at USAA.

A short, little book by Tal Ben-Shahar lays out three ways to be happier and backs them up with a series of useful exercises.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Fully 78% of insurers have begun the journey with policy administration systems, but configuration tools are posing a challenge.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Karen Furtado, a partner at SMA, is a recognized industry expert in the core systems space. Given her exceptional knowledge of policy administration, rating, billing and claims, insurers seek her unparalleled knowledge in mapping solutions to business requirements and IT needs.

Private equity firms are showing great interest in buying workers' comp services firms, and that will likely persist for four reasons.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Joseph Paduda, the principal of Health Strategy Associates, is a nationally recognized expert in medical management in group health and workers' compensation, with deep experience in pharmacy services. Paduda also leads CompPharma, a consortium of pharmacy benefit managers active in workers' compensation.

Muzzlers work on a need-to-know basis -- and think you don't need to know. Here are three ways to root out these cancers and help your business.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

The workers' comp industry clearly requires change but seems to be impervious. Some healthy disrespect, a la Google's Larry Page, could help.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Karen Wolfe is founder, president and CEO of MedMetrics. She has been working in software design, development, data management and analysis specifically for the workers' compensation industry for nearly 25 years. Wolfe's background in healthcare, combined with her business and technology acumen, has resulted in unique expertise.

Public WiFi can be hacked with ease -- and the potential exposure is huge both for individuals and for businesses.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Byron Acohido is a business journalist who has been writing about cybersecurity and privacy since 2004, and currently blogs at LastWatchdog.com.

In the face of the threat of possible new competitors, agents and insurers must cooperate on digital means for better engaging clients.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Dax Craig is the co-founder, president and CEO of Valen Analytics. Based in Denver, Valen is a provider of proprietary data, analytics and predictive modeling to help all insurance carriers manage and drive underwriting profitability.

As the company learned with Windows 8, even a massive ad campaign can't save a lousy product or reverse a crummy customer experience.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Jon Picoult is the founder of Watermark Consulting, a customer experience advisory firm specializing in the financial services industry. Picoult has worked with thousands of executives, helping some of the world's foremost brands capitalize on the power of loyalty -- both in the marketplace and in the workplace.

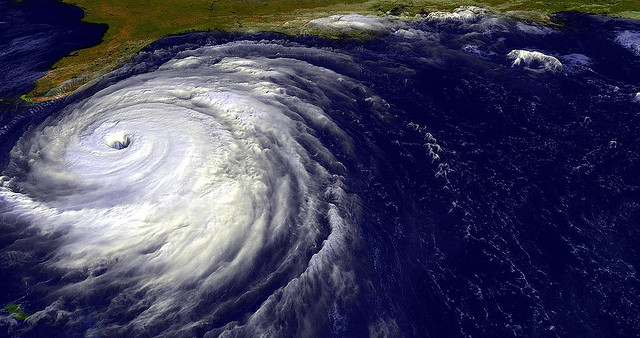

It shouldn’t be so quiet: The warmer the Atlantic Ocean is, the more potential there is for hurricanes to develop.

Last year’s hurricane season passed off relatively quietly. Gonzalo, a Category 2 hurricane, hit Bermuda in October 2014, briefly making the world’s headlines, but it did relatively little damage, apart from uprooting trees and knocking out power temporarily to most of the island’s inhabitants. It is now approaching 10 years since a major hurricane hit the U.S., when four powerful hurricanes -- Dennis, Katrina, Rita and Wilma -- slammed into the country in the space of a few months in 2005.

There have been a number of reasons put forward for why there has been a succession of seasons when no major storms have hit the US. It shouldn’t be so quiet. Why?

Put simply, the warmer the Atlantic Ocean is, the more potential there is for storms to develop. The temperatures in the Atlantic basin (the expanse of water where hurricanes form, encompassing the North Atlantic Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea) have been relatively high for roughly the past decade, meaning that there should have been plenty of hurricanes.

There have been a number of reasons put forward for why there has been a succession of seasons when no major storms have hit the U.S. They include: a much drier atmosphere in the Atlantic basin because of large amounts of dust blowing off the Sahara Desert; the El Niño effect; and warmer sea surface temperatures causing hurricanes to form further east in the Atlantic, meaning they stay out at sea rather than hitting land.

Although this is by far the longest run in recent times of no big storms hitting the U.S., it isn’t abnormal to go several years without a big hurricane. “From 2000 to 2003, there were no major land-falling hurricanes,” says Richard Dixon, group head of catastrophe research at Hiscox. “Indeed, there was only one between 1997 and 2003: Bret, a Category 3 hurricane that hit Texas in 1999.”

There then came two of the most devastating hurricane seasons on record in 2004 and 2005, during which seven powerful storms struck the U.S.

The quiet before the storm

An almost eerie calm has followed these very turbulent seasons. Could it be that we are entering a new, more unpredictable era when long periods of quiet are punctuated by intense bouts of violent storms? It would be dangerous to assume there has been a step change in major-land-falling hurricane behavior.

“Not necessarily,” Dixon says. “Neither should we be lulled into a false sense of security just because no major hurricanes -- that is Category 3 or higher -- have hit the U.S. coast.” There have, in fact, been plenty of hurricanes in recent years -- it’s just that very few of them have hit the U.S. Those that have -- Irene in 2011 and Sandy in 2013 -- had only Category 1 hurricane wind speeds by the time they hit the U.S. mainland, although both still caused plenty of damage.

The number of hurricanes that formed in the Atlantic basin each year between 2006 and 2013 has been generally in line with the average number for the period since 1995, when the ocean temperatures have risen relative to the "cold phase" that stretched from the early 1960s to the mid-1990s. On average, around seven hurricanes have formed each season in the period 2006-2013, roughly three of which have been major storms.

“So, although we haven’t seen the big land-falling hurricanes, the potential for them has been there,” Dixon says.

Why the big storms that have brewed have not hit the U.S. is a mixture of complicated climate factors -- such as atmospheric pressure over the Atlantic, which dictates the direction, speed and intensity of hurricanes, and wind shear, which can tear a hurricane apart.

There have been several near misses: Hurricane Ike, which hit Texas in 2008, was close to being a Category 3, while Hurricane Dean, which hit Mexico in 2007, was a Category 5 -- the most powerful category of storm, with winds in excess of 155 miles per hour.

That’s not to say there is not plenty of curiosity as to why there have recently been no powerful U.S. land-falling hurricanes. This desire to understand exactly what’s going on has prompted new academic research. For example, Hiscox is sponsoring postdoctoral research at Reading University into the atmospheric troughs known as African easterly waves. Although it is known that many hurricanes originate from these waves, there is currently no understanding of how the intensity and location of these waves change from year to year and what impact they might have on hurricane activity.

Breezy optimism?

The dearth of big land-falling hurricanes has both helped and hurt the insurance industry. Years without any large bills to pay from hurricanes have helped the global reinsurance industry’s overall capital to reach a record level of $575 billion by January 2015, according to data from Aon Benfield. But, as a result, competition for business is intense, and prices for catastrophe cover have been falling; a trend that continued at the latest Jan. 1 renewals.

We certainly shouldn’t think that next year will necessarily be as quiet as the past few have been. Meanwhile, the values at risk from an intense hurricane are rising fast. Florida -- perhaps the most hurricane-prone state in the U.S. -- is experiencing a building boom. In 2013, permissions to build $18.2 billion of new residential property were granted in Florida, the second-highest amount in the country behind California, according to U.S. government statistics.

“The increasing risk resulting from greater building density in Florida has been offset by the bigger capital buffer the insurance industry has built up,” says Mike Palmer, head of analytics and research at Hiscox Re. But, he adds: “It will still be interesting to see how the situation pans out if there’s a major hurricane.”

Of course, a storm doesn’t need to be a powerful hurricane to create enormous damage. Sandy was downgraded from a hurricane to a post-tropical cyclone before making landfall along the southern New Jersey coast in October 2012, but it wreaked havoc as it churned up the northeastern U.S. coast. The estimated overall bill has been put at $68.5 billion by Munich Re, of which around $29.5 billion was picked up by insurers.

Although Dixon acknowledges that the current barren spell of major land-falling hurricanes is unusually long, he remains cautious. “It would be dangerous to assume there has been a step change in major-land-falling hurricane behavior.”

Scientists predict that climate change will lead to more powerful hurricanes in coming years. If global warming does lead to warmer sea surface temperatures, then evidence shows that it tends to make big storms grow in intensity. Even without the effects of climate change, the factors are still in place for there to be some intense hurricane seasons for at least the next couple of years, Dixon argues.

“The hurricane activity in the Atlantic basin in recent years suggests to me that we’re still in a warm phase of sea surface temperatures -- a more active hurricane period, in other words. So we certainly shouldn’t think that 2015 will necessarily be as quiet as the past few have been.”

Storm warning

Predictions of hurricanes are made on a range of timescales, and the skill involved in these varies dramatically. On short timescales (from days to as much as a week), forecasts of hurricane tracks are now routinely made with impressive results. For example, Hurricane Gonzalo was forecast to pass very close to Bermuda more than a week before it hit the island, giving its inhabitants a chance to prepare.

Such advances in weather forecasting have been helped by vast increases in computing power and by "dynamical models" of the atmosphere. These models work using a grid system that encompasses all or part of the globe, in which they work out climatic factors, such as sea surface temperature and atmospheric conditions, in each particular grid square.

Using this information and a range of equations, they are then able to forecast the behavior of the atmosphere over coming days, including the direction and strength of tropical storms. But even though computing power has improved massively in recent years, each of the grid squares in the dynamical models typically corresponds to an area of many square miles, so it’s impossible to take into account every cloud or thunderstorm in that grid that would contribute to a hurricane’s strength.

This, combined with the fact that it is impossible to know the condition of the atmosphere everywhere, means there will always be an element of uncertainty in the forecast. And while these models can do very well at predicting a hurricane’s track, they currently struggle to do as good a job with storm intensity.

Pre-season forecasts

Recent years have seen the advent of forecasts aimed at predicting the general character of the coming hurricane season some months in advance. These seasonal forecasts have been attracting increasing media fanfare and go as far as forecasting the number of named storms, of powerful hurricanes and even of land-falling hurricanes. Most are not based on complicated dynamical models (although these do exist) but tend to be based on statistical models that link historical data on hurricanes with atmospheric variables, such as El Niño.

But as Richard Dixon, Hiscox’s group head of catastrophe research, says: “There is a range of factors that can affect the coming hurricane season, and these statistical schemes only account for some of them. As a result, they don’t tend to be very skillful, although they are often able to do better than simply basing your prediction on the historical average.”

It would be great if the information contained in seasonal forecasts could be used to help inform catastrophe risk underwriting, but as Mike Palmer, head of analytics and research for Hiscox Re, explains, this is a difficult proposition. “Let’s say, for example, that a seasonal forecast predicts an inactive hurricane season, with only one named storm compared with an average of five. It would be tempting to write more insurance and reinsurance on the basis of that forecast. However, even if it turns out to be true, if the single storm that occurs is a Category 5 hurricane that hits Miami, the downside would be huge.”

Catastrophe models

That’s not to say that there is no useful information about hurricane frequency that underwriters can use to inform their underwriting. Catastrophe models provide the framework to allow them to do just that. These models have become the dominant tools by which insurers try to predict the likely frequency and severity of natural disasters.

“A cat model won’t tell you what will happen precisely in the coming year, but it will let you know what the range of possible outcomes may be,” Dixon says.

The danger comes if you blindly follow the numbers, Palmer says. That’s because although the models will provide a number for the estimated cost, for example, of the Category 5 hurricane hitting Miami, that figure masks an enormous number of assumptions, such as the expected damage to a wooden house as opposed to a brick apartment building.

These variables can cause actual losses to differ significantly from the model estimates. As a result, many reinsurers are increasingly using cat models as a starting point to working out their own risk, rather than using an off-the-shelf version to provide the final answer.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Dr. Michael Palmer is head of analytics and research for Hiscox Re. Palmer has a research background from Oxford University, where he completed a PhD in atmospheric science, carrying out climate model experiments to investigate climate change. This was followed by work at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, on the tropical upper atmosphere's impact on the weather at the surface.