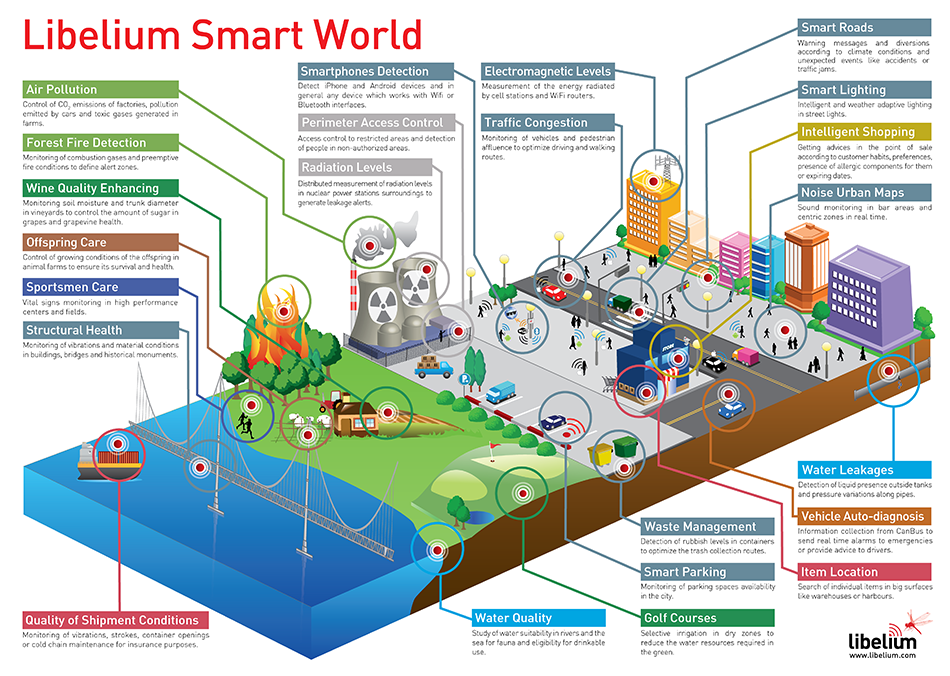

As part of a broad need for more governance but less government, communities need to share risk on health, agriculture and more.

Since independence, all governments of India have committed to gradual rather than revolutionary means for spreading democratic and socialist principles (as attested notably by the preamble to the constitution of India). Independent India averted the revolutions (and most of the debates) that have shaped the role of the state in the western world for some 500 years. In recent history, India never had to face its Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John Stuart Mill, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Karl Marx, Beatrice and Sidney Webb, Franklin Delano Roosevelt or Margaret Thatcher, John Maynard Keynes or Milton Friedman. India was saved the horrors of the French, American, Russian, Turkish, Cultural (Chinese) or Iranian revolutions (to mention but a few). India was largely spared the two World Wars and most of the “…isms” (fascism, communism, Marxism, capitalism, etc.). For every political fad that swore by TINA (“There Is No Alternative”), India responded with its inimitable TATA (“There Are Thousands of Alternatives”). It had its gradual transition away from non-democratic practices (e.g., abolition of privy purses in 1971 and of debt bondage in 1976) to a welfare democracy. Even the embrace of the “Washington consensus” (a combination of open markets and prudent economic management) under the guidance of Manmohan Singh has not changed the essential nature of the state.

This “Fabian” model meant that the state was committed to provide welfare, not merely security, to the citizens, and that central government was in the main responsible for funding, producing, procuring, allocating and distributing most goods and services. This has been done in large measure through subsidies to public enterprises, producers of inputs, private-sector producers and consumers. The goods and services whose availability and price have been modified through subsidies include food, water, energy, financial services, labor, education, healthcare, fertilizers, information and media. As the public demanded more and more, the state promised more and more, sometimes through milestone measures (e.g., the largest debt waiver and debt relief program for farmers, in 2008) but mainly through quasi-permanent subsidies, which have led to a sizable fiscal deficit (almost 75% of the 2014-15 budget estimate, and 4.1% of GDP). The net cost of these handouts and subsidies is much higher than their nominal value, for three reasons: the interest payable to fund the deficit, the losses because of intermediation (e.g., it has been reported that for every kilogram of subsidized grains delivered to the poor, the government released 2.4 kg from the central pool) and the societal effects of enhanced inequity (an IMF working paper titled "The fiscal and welfare impacts of fuel subsidies in India" argued that the richest 10% of the households benefited from fuel subsidies seven times more than the poorest 10%).

This is why a policy of “less government” could have much scope by divesting ownership of public sector undertakings (PSUs) in manufacturing, services and distribution and reducing subsidies substantially. However, the existing system has created many winners that would presumably be motivated and suitably represented to protect their vested interests by militating for status quo. Additionally, certain social services must be improved considerably (mainly water-sanitation-health, financial protection, food security and education), but acting on those needs would lead to more rather than less government. Similarly, actions to remedy inequitable targeting and inefficient distribution of subsidies could bring “more governance” only if preceded by more government intervention and spending.

So, what is the road to “less government and more governance” that would both engage the many who today enjoy representation without taxation and protect future taxpayers from the financial and societal ramifications of today’s consumption? We submit the answer is in “localism.”

“Localism” means encouraging people to be involved in elaborating and governing local solutions, with only subsidiary support from government. Most of India’s population is rural and in the informal sector. For this vast majority, the world is local, and local is the measure for most things. It is a moot point to argue whether people wish to be in the informal sector (to be excluded from the framework through which the government collects taxes and imposes regulations) or whether they are victims of circumstances (of being de facto excluded from the practical measures through which the government delivers universal rights for all citizens). The essential point is that people belong to local groups through which they access benefits that are not otherwise available as public goods. Therefore, communities reinforce the norms and networks that enable individuals to act collectively, influence decisions of single community members on the economic and social engagements they can/must/must not enter into, who can/cannot do so and on how benefits are distributed. Compliance with consensus flows from members’ reliance on the community’s patterns of reciprocity. As the community reaches most everybody on a continuing basis, it can be mobilized to play a role in “more governance” of local activities and structures.

Experience from rural India and from other countries confirms that underserved rural communities have been able to operate community-based mutual-aid schemes that create welfare and distribute benefits, which are funded by resources of the members. Such collective action of groups, by groups and for group members is a major paradigm shift from the mentality of reliance on government handouts, decisions and entitlements. The change in mindset is from being dependent to being dependable; the change in the financial model is from relying on inflow of charity to relying on pooling of own funds, which are otherwise invisible and inaccessible, to obtain welfare gains. The argument in favor of empowering community-based mutual aid is not merely that it is more opportune, but that it is more legitimate. Recalling the words of Abraham Lincoln (a speech from 1854, quoted in G.S. Boritt, 2004: Lincoln and Democracy): “the objective of government is to do for a community of people whatever they need to have done but cannot do at all or cannot so well do for themselves in their separate and individual capacities.” If now the case is that communities of people can do for themselves what the government cannot so well do for them, is it not then self-explanatory that the government should do all it can to support such action at the local level? Moreover, the argument in favor of encouraging the proliferation of local action is consistent with the democratic system of India, where interest groups are well established. In his book The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (1965), M. Olson pointed out that small local groups can form more easily and function more effectively to advance their interests. Olson also asserted that it is easier for the government to support many small groups than few large ones, and by supporting community-based self-interest the state can also advance its interests more easily and less expensively. If the reason for seeking “less government” is to encourage more self-reliance and hard work and a decrease in dependence on acquired rights and corruption, then does it not follow that government should provide tangible support to encourage voluntary action? The pooling of part of people’s resources for the advancement of community-based welfare gains serves the interest of the members of such groups (who can take charge of rationing and of priority-setting relating to the use of their funds) and also of the government (which could leverage the community-based risk management by limiting its intervention to subsidiary coverage of only rare events).

The development of community-based health insurance in India as a mutual-aid activity, replacing entitlements or debt, is one of the most effective mechanisms for voluntary social change.

Just as after independence India abolished several homegrown systems based on inequality of rights (e.g., chaudhary, deshmukh, jagir, samanta and zamindar) and favored equality through democracy, so asset creation should take primacy over money lending (in all its forms, from village shark to microfinance and to banks), for the same reason. India also abolished bonded labor (which also involves interlinking debt and exploitative labor agreements), even if this practice is not yet dismantled completely, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO). And the infamous phenomenon of farmer suicides is also linked, at least in part, to debt: Farmers are held morally deficient for inability to repay loans, when in fact the reason for that insolvency is crop failure (occasioned by the inherent risks of agriculture: too much or too little rain, too hot or too cold climate, pests etc.). Many other countries developed crop insurance to protect both farmers and farming. In India, agricultural insurance is used mostly to securitize loans rather than farming (farmers must pay the premium when they borrow, but the payout goes to the lending bank).

Disconnecting crop insurance from borrowing and connecting it with “what a responsible adult does” to avert the risks of agriculture can bring about safer agriculture and more governance with less government. This change is best accomplished when embraced by local communities, not merely single individuals. When agriculture is a safer economic activity, more farmers are likely to continue farming (and thus provide food security). When crop insurance becomes an act of mutual aid, something everybody in our village does, it is easier to mobilize the community to also encourage asset creation, and better financial protection. The virtuous cycle of more community-based cooperation fosters multiple positive changes, including improved targeting of government support for financial protection, better advisory to farmers on how to improve their agricultural productivity and thus food security and enhanced equality. These are objectives that have never been achieved by debt/credit extension or debt relief, because such programs missed completely the opportunity to leverage the collective energy that, what the community can do together, none of its members can do alone.

Creation of such local asset pools may start with modest amounts, as many villagers are cash-poor, and will first want to gain trust that the new form of collective action will deliver welfare to many members of the group, not just to a few powerful or privileged persons. However, the accumulation of funds will grow over time, especially if such growth is stimulated by the government. The government can encourage such solidarity-based collective action by passing enabling regulations to recognize mutual and cooperative insurance schemes (as part of the revision of the insurance law). Indonesia has recently changed its insurance law to recognize mutual and cooperative insurance at par with commercial insurance, to facilitate the development of mutual micro-insurance in rural communities. The European experience has shown that today’s large financial institutions originated from exactly such community-based local initiatives. As these were allowed and supported to grow, they served as the basis for universalization of health insurance, agricultural insurance and natural catastrophe insurance. In some countries (e.g. Switzerland, France, the Netherlands, Belgium or South Africa) ,the local schemes have morphed into large private or cooperative insurance companies. The local origin of the activity was essential to ensure that local groups can define their local priorities (which enhance local willingness to pay) and operate their scheme with locally dependable persons (which enhances flow of information, notably through gossip, about the fair and equitable treatment of all members of the scheme).

Government support for community-based asset creation can provide the government with information that it does not have currently but that it needs to enhance governance and the government’s revenue side. The shift from remote governance to local governance relies on local trusted elites, a new kind of elite, different from the capitalist elite and the bureaucratic elite. The local elite needs to be given a good start (by imparting private sector methods for social sector activities, minus the profit-taking), and the government must still provide worst-case protection. But for the rest, government should encourage communities to devote their talents to create public goods, to fend for themselves, to concentrate on assuming responsibility for their own welfare.

This is so much better than the present situation, in which many people entertain huge, unrealistic expectations and contradictory demands from the government based on messages, disseminated for years, that welfare is a right; and when they receive welfare or debt/credit benefits, rather than being grateful, many people feel that their due has reached them too little and too late. Anchoring the support to local asset-building by community-based collective action enhances the notion that we can do more on our own and allows each local group to design and do itself some of the work that hitherto it waited for the government to do. Supporting “localism” means that welfare creation is the legitimate domain of each community, delivered bottom-up rather than entirely top-down, supported by the government rather than the exclusive responsibility of the state to each individual. Localism will enhance governance because communities, governing their own priorities and resources, are very good regulators of their local scheme, because they are responsible for doing, not debating, and their actions are transparent locally. This transition from external to community leadership entails transition to performance-related legitimacy and away from formal title or appointment. It can also be the transition from short-termism (with the next elections as implied statute-of-limitations) to the long-term, recognizing that to achieve universal access to financial services, or to health insurance, or to secured livelihoods, or to relevant agricultural insurance or better sanitation may take decades. Notwithstanding the patience needed to get results, localism can provide the platform for less government and more governance now.