Workers' Comp Is Under Attack

Workers' comp is under attack from all sides. Employers are sick and tired of the expense and their lack of control. So are workers.

Workers' comp is under attack from all sides. Employers are sick and tired of the expense and their lack of control. So are workers.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

David DePaolo is the president and CEO of WorkCompCentral, a workers' compensation industry specialty news and education publication he founded in 1999. DePaolo directs a staff of 30 in the daily publication of industry news across the country, including politics, legal decisions, medical information and business news.

To see how effective you are, you need a combination of technical skills and must measure "above the line" and "below the line."

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Paul Laughlin is the founder of Laughlin Consultancy, which helps companies generate sustainable value from their customer insight. This includes growing their bottom line, improving customer retention and demonstrating to regulators that they treat customers fairly.

After decades of efforts to enact NARAB, more hard work lies ahead to implement the interstate clearinghouse for licensing nonresidents.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Joel Wood is senior vice president of government affairs at the Council of Insurance Agents & Brokers, a position he has held since 1992. Dubbed one of the top trade association lobbyists in Washington by “The Hill,” Wood is a regular contributor to Leader's Edge magazine.

The author, a longtime critic of claims that corporate wellness programs deliver a return on investment, says he has reconsidered his position.

April Fools.

Of course wellness doesn’t save money. Even the industry trade association itself, the Health Enhancement Research Organization, admits wellness loses money.

That doesn’t mean the industry lacks other benefits, such as levity. And in the spirit of the wellness field’s most appropriate holiday, we present “On the (Even) Lighter Side,” a compendium of the funniest moments in recent wellness history.

Unfortunately, the joke is that wellness is not a joke. Besides damaging morale, things are being done to employees that could even harm them -- medical interventions that the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) urges not be done. Even routine screens that are done to employees -- only for cholesterol and related blood values -- shouldn’t be done annually, and shouldn’t be done on everyone, according to the USPSTF.

Still, we’ll let it go this one day and urge you to do the same and enjoy the one contribution that wellness advocates are bringing to the healthcare policy debate: merriment.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Al Lewis, widely credited with having invented disease management, is co-founder and CEO of Quizzify, the leading employee health literacy vendor. He was founding president of the Care Continuum Alliance and is president of the Disease Management Purchasing Consortium.

When the tables turned and the author became a software customer, "the loftiness of strategic vision met the cold, hard pavement of execution."

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Eileen Maier is vice president, sales consulting, at Guidewire Software. She oversees global pre-sales support and the development of sales enablement programs for the extended team of Guidewire sellers. Maier started her career at Liberty Mutual Insurance and has spent the last 10 years with Guidewire.

The first step on cyber security is to get our heads out of the sand and understand that we are all, collectively and individually, at risk.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Norman Marks has spent more than a decade as a chief audit executive (CAE) for major companies, with as much as $28 billion in annual revenue. He has implemented risk management, ethics programs and disclosure processes at multiple organizations.

To maintain healthcare profits, key players resist transformational change and use the power of political lobbying, fear and confusion.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Craig Lack is "the most effective consultant you've never heard of," according to Inc. magazine. He consults nationwide with C-suites and independent healthcare broker consultants to eliminate employee out-of-pocket expenses, predictably lower healthcare claims and drive substantial revenue.

With property claims, the assumption is: Submit your invoices, and your insurer sends you a check. If only the process were that simple.

When a property claim occurs, with or without business interruption, it is very common to assume that it will be straightforward. Just submit your invoices, and your insurer sends you a check. You may think, "We can do it ourselves," or, "We have it under control." If this has been your approach, you need to read on.

There are many potential issues when preparing a property claim that are commonly overlooked or misunderstood. The challenge is even greater if there is a business interruption component to your claim.

From experience, my partners and I have identified the most common property claim issues that can slow down the claim process and have an adverse affect on recovery.

Repair vs. replacement comes up in almost every significant property claim. The issue arises when it becomes a battle of opinions and assumptions. We all know the humor on opinions and assumptions -- but your property damage claim is no laughing matter, so let's explore what can happen.

If you have a replacement policy, you have the option to repair or replace. If it makes more sense to replace with a new and improved item, then you should do what's best for your business. However, if repairs are possible and at a lower cost, the adjuster will undoubtedly dispute the claim, and you'll be debating a matter of opinion. When the adjuster's experts recommend repairs that you know are not guaranteed to work, especially long-term, you face a challenge. As a business, you cannot afford to risk a failed repair, so you elect to go with new equipment with a warranty. The repair option will now be a theoretical scenario that your insurer can leverage to adjust your claim payment. Regardless of the adjuster's position, you did what was best for your business, but there's a way to neutralize this potential adjustment.

Losses often present opportunities to make useful changes and improvements to operations. Adjusters anticipate this and will be prepared with reasons to limit recovery by labeling certain repairs, reconfigurations, and replacements as betterments. Most of the time, newer is better, and that is why you pay for a replacement policy. However, just because something is better does not mean you should not get full replacement value.

Let's say you are replacing a piece of production equipment that was damaged as part of your loss. In searching for a replacement, you find that the as-was capacity replacement for your equipment is no longer available and that the alternative equipment has a 10% greater production capacity than the damaged property. In this case, the adjuster may argue for a credit for the increased capacity. Though the new equipment is clearly a benefit to your business, because the exact model that is being replaced is no longer available, you don't have an equivalent alternative. If required to justify and validate your decision, simply compare the cost/time differential between your decision and a custom order built to spec. In cases like this, you should not be penalized for the betterment.

There are valid adjustments for betterments, but it's important to understand the difference between a betterment and your rights to a replacement of like kind and quality.

From a policyholder perspective, the types of expenses related to the claim do not really matter because they are necessary to get back in business. The insurance company, however, needs to see expenses segregated into their proper insurance claim buckets. To ensure a smooth claim process, knowing how best to account for expenses is critical to the outcome of your claim. Let's say you have payroll expenses for cleanup and remediation. If you consider that property and extra expense are subject to different limits and deductibles, it makes good sense to claim them according to your coverage limits. As a rule of thumb, look at the property bucket first for expenses related to cleanup and repair of the property because the extra-expense bucket will offset business interruption, thus allowing you to operate as normally as possible during the indemnity period.

As an example, assume you have production labor working overtime to keep production going and to clean up and repair damage from the loss. This time should be separated as normal labor, property damage cleanup and repair and extra expense. To complicate things further, both normal rates and overtime rates need to be factored into each calculation. Finally, you have to keep detailed records that document the who, what, when and where that is involved in the work being done.

Remember, when appropriate, it's best to claim expenses as property damage, provided the costs can be documented. It is a more tangible approach and will avoid conflicting with the business interruption calculations for extra expense and inefficiencies, which are based on assumptions and subject to debate.

Immediately after a loss, you are entitled to recover the documented actual cash value (ACV) of your damaged property. You may claim ACV as the amount you are due before exploring replacement options. This is a good tactic if you want to get the cash flowing early in the process while the replacement values are being determined and decisions on replacement are made. However, accurately determining ACV can be challenging.

Typically, the starting point is the asset ledger that shows a depreciated value of the asset. However, this number is usually used for tax purposes and may not represent the actual value of the asset. Other options to value the asset include pricing based on what a willing buyer would pay or replacement less physical depreciation based on the actual life of the asset. These methods vary state by state. Do your research to value the asset appropriately under the circumstances and know that there is not one right answer.

Additionally, some policies allow you to recover full replacement value for assets even if you do not replace them. The policies usually require that you spend the money on a capital project that was not approved at the time of the loss. The capital improvement does not necessarily have to replace capability of the lost assets. If this is of interest, check with your broker about adding this option to your program.

In general, the period of indemnity is the length of time it takes (or should take) to make property repairs. Once repairs are complete or should have been complete, the period of indemnity terminates. While you can, and should, attempt to settle portions of the property claim as you go, any agreements related to the property side of your claim can have a costly impact on the indemnity period for the time-element portion of the claim. It is critically important to address property issues in tandem with time element, to avoid unnecessary recovery issues.

This can be a little confusing. As an example, let's assume you have a total loss to a piece of equipment, and the replacement cost is known. It would be reasonable to settle for the replacement cost of that equipment. However, the adjuster assumes an aggressive timeline to order and install the equipment, not considering how installation might affect continuing production. When this happens, make sure the timeline and assumptions for installation are clear and acceptable before settling on the cost to replace the equipment. Otherwise, you might get what you want on the property settlement and then lose on the time element.

If you have a separate team working on the property and time-element claims, collaboration is essential to avoid assumption-based adjustments, This becomes especially important when repairs are theoretical, as this will be the basis for the time-element recovery. Always remember to consider all assumptions needed for time-element claims as part of any property settlement.

If you have a significant property claim, you may need to purchase equipment or supplies on a temporary basis. The validity of these purchases is not in question, but their use once permanent repairs are made is. For items such as this, the adjuster may look to take a residual value credit. Essentially, the adjuster agrees that you needed that item, but when the permanent repairs are made (and paid for), you will no longer need it. This may be true, but this does not always mean you should not get full value for the item.

For example, you have an electrical loss that will keep you out of business for an extended period. You purchase a generator to provide basic power to areas of your business. When repairs are complete and power is restored, you no longer need the generator but still have the unit. Because you still have it, the adjuster takes a residual value credit. Is that fair?

The first question you need to ask is whether you want to keep the generator. If there is some value to you, a fair credit can be negotiated with the insurance company. If you do not want to keep the item or do not feel the credit is reasonable, you can have the insurance company take possession -- after all, the insurer paid for it. If the insurance company thinks it can get value from the generator by taking possession and selling it, the company will probably take you up on this. More often than not, this is not cost-effective, and you can minimize or eliminate the residual value credit.

If you have never been through a significant property claim, you might not appreciate the level of detail that is required to document your claim. The general perception is that you gather some invoices and quotes on a sample basis, and that should be enough. Unfortunately, the requirements for an insurance claim are more detailed than most capital projects and audits. Quotes and estimates need to be extremely detailed, and proof of payment needs to be documented almost entirely -- if you cannot properly document a claim, it will likely not be paid. It may not be acceptable to the insurance company to use a dollar threshold for charges because the company will insist on auditing 100% of the charges.

To demonstrate the level of scrutiny that claims come under, I refer to an experience I had on one of the largest claims I worked on. The property portion of the claim was close to $200 million. Months of work and tons (literally) of paper were presented to support this claim. During a meeting between the accountants and engineers, one of the engineers made copies for everyone of one invoice presented for payment. He adamantly pointed out that the invoice had been duplicated in our claim submission. It was for one $5 roll of duct tape.

The point is that handling and organizing all the documentation required to support your claim can be daunting. To avoid mistakes, it is advisable to assign a dedicated person or team to locate, scan, print and manage all the support documentation. Bringing in an expert forensic accountant is always a good option to consider, especially for larger, complicated claims or just to relieve your team from these tedious and burdensome tasks. Forensic accountants that specialize in claim preparation may be covered in your policy to work on your behalf. Though you will still have some work to do, your claim will go more smoothly, with fewer pitfalls.

Now you know why property claims are not as easy and straightforward as you might expect. After decades of preparing claims for policyholders, we can attest that what you don't know comes at a cost in both time and money. We hope the information above can help you prepare for at least some of the issues you might encounter should you have a future property damage claim.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Christopher B. Hess is a partner in the Pittsburgh office of RWH Myers, specializing in the preparation and settlement of large and complex property and business interruption insurance claims for companies in the chemical, mining, manufacturing, communications, financial services, health care, hospitality and retail industries.

In the digital revolution, insurers must recognize that a one-size-fits-all channel model is obsolete and must find new ways to touch customers.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Denise Garth is senior vice president, strategic marketing, responsible for leading marketing, industry relations and innovation in support of Majesco's client-centric strategy.

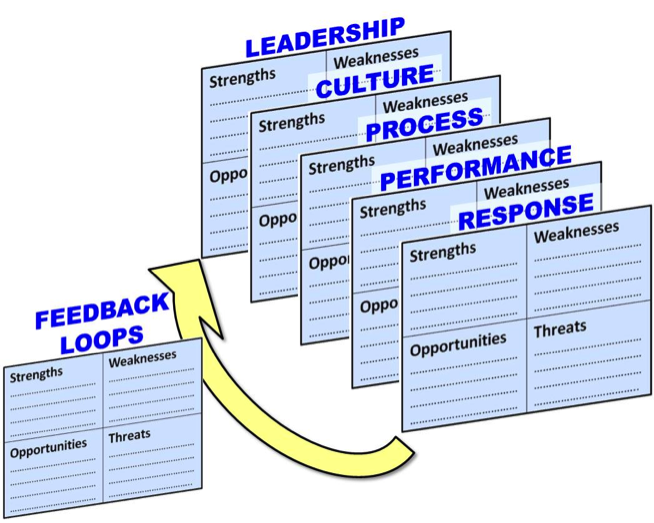

Looking at SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) can be a great start but must move to a deeper level of sophistication.

Figure 1. Each element of internal cascades should be SWOT-ed separately with candid and honest inputs from all levels of employees

SWOT expansion to include external cascading risk assessments

External risks need to be listed, rated for connectedness and assessed for their impact and likelihood of affecting the business. This offers a good start for subsequent strategic risk management efforts. The World Economic Forum's annual Global Risk Report offers a good reference to use as a starting point for possible risks to consider. Separate SWOT analysis should be carried out for the six main areas of global risks:

Figure 1. Each element of internal cascades should be SWOT-ed separately with candid and honest inputs from all levels of employees

SWOT expansion to include external cascading risk assessments

External risks need to be listed, rated for connectedness and assessed for their impact and likelihood of affecting the business. This offers a good start for subsequent strategic risk management efforts. The World Economic Forum's annual Global Risk Report offers a good reference to use as a starting point for possible risks to consider. Separate SWOT analysis should be carried out for the six main areas of global risks:

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

David Patrishkoff is president of E3 (Extreme Enterprise Efficiency) and the founder of the Institute for Cascade Effect Research. He is a Lean Six Sigma Master Black Belt and the inventor of a cascading risk management methodology that has patent pending status.