Workers' compensation is a no-fault form of insurance that an employer is legally obligated to secure, providing wage replacement as well as medical, rehabilitation and death (survivor) benefits to employees injured in the course of employment. Workers' comp is in exchange for mandatory relinquishment of the employee's right to sue his or her employer for the tort of negligence. The lack of recourse outside the workers' compensation system is sometimes referred to as "the compensation bargain." This compromise system also establishes limits on the obligations of employers for these workplace exposures, so that the costs are supposedly more predictable and affordable.

The system is always evolving, and there are key choices in workers' comp, which I will cover here -- and update as the system continues to evolve.

First, some background:

Where did workers' comp come from?

Workers' compensation has roots all the way to 2050 B.C., where ancient Sumerian law outlined compensation for injury or impairment involving loss of a worker’s specific body parts. Beginning in the 17th century, most pirate crews, including the one led by English privateer Capt. Henry Morgan, organized fairly sophisticated and favorable benefits for injured crew members. Injured pirates were treated on board and fitted for prosthetics - as popularized in literature and film. Furthermore, they were compensated in pieces of eight depending upon the type and severity of injury. As for modified duty, crew members were oftentimes offered non-physically demanding work on the ship. Such work could include cleaning cannons, cooking meals and washing the ship decks.

In modern times, workers' comp as we know it today was first modeled in Germany and Prussia in the late 19th century, then adopted in the U.S. in 1908 by the federal government, then in 1911 by Wisconsin. Workers' comp spread to all states and the District of Columbia by 1948, with Mississippi as the last state to adopt the model.

Why is workers' comp coverage mandated?

At first, participation in U.S. workers' compensation programs was voluntary. In 1917, however, after the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of compulsory workers' comp laws, the majority of states then passed legislation that required employers to purchase workers' compensation coverage for their employees. Requirements varied -- and still vary -- from state to state. Currently, Texas and Oklahoma have voluntary "opt-out" or "non-subscription" provisions, which allow employers to provide their own formal injury benefit plan options.

How is workers' comp different from other insurance?

Workers' comp is intended to eliminate tort liability litigation arising from employee injuries or work-related diseases by providing wage replacement, vocational rehabilitation and medical benefits to employee injured in the course and scope of their employment. This is intended to minimize worker conflicts and to avoid costly lawsuits. The standard workers' compensation insurance policy is a unique insurance contract in many respects. Unlike other liability insurance policies, it doesn't have a dollar amount limit to its primary coverage. The coverage is considered "exclusive remedy," to deny employees the opportunity to sue their employee. In general, an employee with a work-related illness or injury can get workers' compensation benefits regardless of who was at fault -- the employee, the employer, a coworker, a customer or some other third party.

Why does a workers' comp policy have two parts?

Part One is the standard workers' compensation insurance policy (formerly known as Coverage A) that transfers liability for statutory workers' compensation benefits of an employer to the insurance company. If a state increases benefit levels during the term of the policy, the employer doesn't have to make any adjustments to the policy. Instead, the policy automatically makes it the responsibility of the insurance company to pay all claims due for workers' compensation insurance for the named employer in the particular states covered by the policy.

Part Two (formerly known as Coverage B) addresses employers' liability coverage. This coverage protects the employer against lawsuits brought by the injured employee or the survivor. If an employer is thought to be grossly negligent, the employer runs the risk of being sued for that negligence. Under Part Two of the workers' comp policy, the employer would be defended in such a suit. If a judgment were rendered against the employer, that judgment would be paid by the workers' comp coverage, but no more than the limits provide for in the policy. Part Two also insures an employer in cases such as third-party "over suits," where an injured worker sues a third party and that third party seeks to hold the employer responsible.

How states differ

Examine your company's possible exposures to workers' compensation claims from different states. If you have employees who live and work in or who travel to other states, you need to make sure you are properly covered in each state. In most jurisdictions, employers can meet their workers' compensation obligations by purchasing an insurance policy.

Five states and two U.S. territories (North Dakota, Ohio, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Washington, West Virginia and Wyoming) require employers to get coverage exclusively through state-operated ("monopolistic") funds. If you're an employer doing business in any of these jurisdictions, you need to obtain coverage from the specified government-run fund unless you’re legally self-insured. A business cannot meet its workers' compensation obligations in these jurisdictions with private insurance.

Thirteen other states also maintain a state compensation insurance fund, but their state funds compete with private insurance. In these states, an employer has the option (at least theoretically) to use either the state fund or private insurance. Those states that offer employers this option are Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania and Utah.

FORMS OF FINANCING WORKERS' COMP

- Fully Insured

There are more than 300 workers' comp insurers writing policies in the U.S., although many will only provide coverage with a high deductible. Most states have a State Fund Insurance Carrier that is the insurer of last resort and provides fully insured (no deductible) workers' comp coverage to entities operating in their state. State fund programs are also referred to as the residual markets. They are more commonly known as state insurance funds, assigned risk plans or workers' compensation pool policies. Generally speaking, state insurance funds are non-profit entities that cost more than private companies (10% to 40% higher premiums) but that guarantee availability of coverage as a "last resort" carrier.

Some common reasons that employers fail to obtain competitive quotes from private carriers include: 1) a high frequency of claims or a high cost of claims; (2) the dangerous nature of the risk or industry (based on codes from the National Council on Compensation Insurance, or NCCI); 3) prior bankruptcies or poor financial status of the business; and 4) prior cancellations because of nonpayment of workers' compensation premiums.

- Group or Association Coverage Plans

In various states, there are options for small to medium-sized companies to obtain group coverage through their industry associations. These options include Self-Insured Groups (SIGs), which provide a true self-insured option. Group members make contributions to the self-insured group, and the self-insured group pays expenses and claims for injured workers.

SIGs directly contract for services normally performed by an insurance company. Services secured on behalf of members include: elected Board of trustees, program administration, safety and loss-control services, third-party administration (TPA), independent accountants and actuaries and excess insurance carrier.

Companies must apply for membership and generally indicate adherence to effective risk management and loss control programs.

- Large-Deductible Plans

This is a form of self-insurance where the employer is responsible for reimbursing the insurer for claims up to a certain dollar amount and the insurer is responsible for paying claims in excess of that deductible. The insured funds an account (loss fund) to pay losses, and the insured reimburses the fund as losses are paid. The insured must collateralize, usually by letter of credit, an amount approximately equal to the difference between paid and ultimate losses. The actuary is typically one assigned by the carrier.

With the advent of the high-deductible program in the early ‘9Os, actuarial efforts focused principally on pricing issues. Employers are able to save significant premium expenses if they manage their loss-control and return-to-work programs effectively. The "deductible" is a sum that is subtracted from the insurer’s indemnity or defense obligation under the policy. Importantly, the responsibility for the defense and settlement of each claim rests almost entirely with the insurer, and the insurer typically maintains control over the entire claim process.

Large-deductible programs were slow to find favor in the U.S. In 1990, only six states approved of such deductibles. Currently, at least 45 states utilize large-deductible programs for workers’ compensation.

Deductibles are based on a per claim or per occurrence basis, with self-insured retentions of $100,000 to $1 million. The insurer sets the minimum deductible allowed. Insurers initially developed this program to provide both themselves and insureds certain advantages, including:

- price flexibility, by passing risk back to the insured

- reduced residual market charges and premium taxes in some states

- better cash flow

- coverage options for aggregate limits

- broadest choice of insurance carriers

- the possibility that a separate TPA may be allowed as an option to the carrier

- that certificates of insurance issued to the employer’s key business partners show full coverage and policy limits

With a well-designed and -managed, loss-sensitive product, companies can potentially lower costs by assuming a greater proportion of their risk. You get increased cash flow and lower costs and improve claims outcomes for the business and its employees. What’s important with a loss-sensitive program is that the organization is committed to fully leveraging the insurer’s loss control, claims, medical and pharmacy management programs.

Additionally, it is critical to choose the right risk-financing structure. That involves having the business itself, you, the agent and the carrier carefully examining the organization’s current financial situation and short- and long-term goals.

Because the carrier is legally responsible for the employer’s claims, the carrier will require collateralization of existing and future claims covered by the policy period. Collateral is usually a letter of credit, surety bond or cash.

Keep in mind, however, that choosing a high retention is all about the frequency and severity of your workers' comp claims as well as the responsiveness and quality of your claims administrator. In essence, the employer is giving the insurance company an open checkbook with respect to the handling and disposition of claims.

- Retrospective (Deferred) Premium Options

Retro programs are written through an endorsement on your large-deductible workers' comp policy. It is the ultimate amount of money you will owe your carrier for the contract period. It can be broken down into installment payments. It consists of basic premium and converted losses, both of which get adjusted by the tax multiplier, which are the taxes and assessments due to the state. The insurer provides you a written agreement that defines the terms of your contract. It will show the basic and maximum and minimum premium, how the premium will be paid during the policy year, how the retrospective premium will be calculated and, most importantly, when you will be eligible for a premium refund. The agreement also defines any penalties associated with a midterm cancellation of the contract.

The two major retro payment plan options:

A. Incurred Loss Retro:

You’ll pay the same up front as with a guaranteed-cost program, but you’ll be refunded money if your loss experience is favorable. The risk, however, is having to pay additional premium if your loss experience is unfavorable. The cost of the insurance program is determined by the actual incurred loss experience for a specific policy period. Incurred costs include paid costs as well as future expected costs (reserves). The premium is adjusted annually until all claims are paid and closed.

B. Paid Loss Retro:

Premiums are determined using paid only loss amounts rather than incurred (reserved amounts). Timing of premium and loss payments are negotiated before inception, and disbursements are made as costs are realized and billed. Because this option is typically the favorite of insureds, this option is typically only offered to large entities paying in excess of $1 million in premium.

How is the basic premium determined?

Basic premium is basically the insurer’s cost of doing business plus expected profitability. The amount is determined by multiplying the standard premium by a percentage called the basic premium factor. This factor varies based on your actual premium size and the amount of risk you are assuming. In general, if you take on more risk for your claims, the amount you will pay for the basic premium decreases.

What are converted losses?

Converted losses are the total claims, also called incurred losses, adjusted by the tax multiplier (see below) and multiplied by the loss conversion factor (LCF), which is negotiated with you prior to the inception of the coverage. As the loss conversion factor increases, you assume more risk, so the basic premium decreases.

What is the tax multiplier?

This is a factor that is applied to the basic premium and converted losses to cover state taxes and assessments that must be paid by your insurance carrier.

What is the maximum premium?

Maximum premium is the most you will have to pay under a retro plan. It helps protect you by placing a limit on the impact of any substantial losses you could have. It can range from 100% up to 150% of audited standard premium. For example, if the audited standard premium was $100,000, and you selected a 125% max, the most you could pay for the total of all retro charges under the specific contract period is $125,000.

When will my money be returned if losses are low?

After completing the full contract period, the first adjustment for a possible refund is usually calculated six months after the policy expiration date. The premium is adjusted according to the retro formula, using the basic premium, converted incurred losses and taxes. If your claim losses are better than expected, you will get as much as 50% of the total estimated refund. Another adjustment is usually made in 12 months, with as much as 25% of the total estimated refund. The final adjustment is at least 12 months after that, with the final 25%. If, however, you have complex indemnity (lost-time) claims that are unresolved, the adjustments may drag out for years.

- Captive Insurance

A captive insurance company is an insurance company formed by a business owner to insure the risks of related or affiliated businesses. A captive permits a business to manage its risks while potentially providing substantial benefits to that related business. More than 75% of the Fortune 500 now utilize some form of captive insurance, but captives are usually not a viable alternative for most small to medium-sized companies.

Is a captive still a viable alternative?

The number of captive insurance entities is growing worldwide. Today, nearly 10,000 businesses in the world employ some form of captive insurance coverage. Those totals are expected to triple over the next 10 years as more companies further examine comprehensive and well-targeted risk-management plans. More than 5,750 large companies have their wholly owned captive insurance entities that were formed to insure the risks of the parent company and its subsidiaries.

What risks does a captive typically underwrite?

Captives are formed in 30 domestic locations (state) or in foreign ("off-shore") domiciles like Bermuda and the Cayman Islands. Vermont is the most popular state. Each domicile has its own set of laws and regulations. To be successful, captives usually cover disparate types of risk, with a good geographical or industry spread. Captives are intended to build financial strength over time and help insulate the parent company from price fluctuations in the traditional insurance market. Increasingly, captives' owners are also looking to their captive to provide broader coverage, including unusual or emerging risks, where risk transfer is either expensive or unavailable.

The type of risks that captives cover is expanding rapidly, from the more common property damage and casualty coverage, to employee benefits, environmental, cyber, business interruption and other non-traditional covers like operational risk and supply chain. Captives typically provide large companies an opportunity to insure against risks that are generally uninsurable or exotic.

Are there different types of captives?

There are at least 10 types of legal insurance captives, including:

- Pure captives (single parent)

- Industry group captives

- Agency captives

- Association captives

- Risk-retention groups (RRGs)

- Rent-a-Captives

- Segregated and protected cell captives

- Special-purpose reinsurance captives

- Series LLC captives

- Internal Revenue Code 831b captives.

How is workers' comp coverage provided in each state?

A commercial insurance company ("fronting company"), licensed in the state where a risk to be insured is located, issues its policy to the insured. That risk is then fully transferred from the fronting company back to the captive insurance company through a reinsurance agreement, known as a fronting agreement. Thus, the insured obtains a policy issued on the paper of the commercial insurance company.

The cost varies for a fronting carrier, which legally assumes the workers' comp risk it fronts, in the event of default by the captive. The fronting company will almost always require collateral to secure the captive's obligations to the fronting company under the fronting agreement, in addition to a 4% to 10% fee.

Is there a tax advantage to using captives?

While the tax advantages from captive arrangements should never be at the top of any company’s list, captives can offer accelerated premium deductions, unlike most self-insurance programs. However, if the IRS believes that a captive has been established purely for tax purposes, the agency may challenge the captive status of the company. Comprehensive documentation of the objectives of the captive structure is important.

- Self- Insurance

A self-insured workers' comp program is one where the employer sets aside an amount to provide for any workers' comp claims and associated expenses—losses that could ordinarily be covered under an insurance program. Self-insurance is a means of capturing the cash flow benefits of unpaid loss reserves and offers the possibility of reducing expenses typically incorporated within a traditional insurance program. It involves a formal decision to retain risk rather than transfer (insure) and allows the employer to pay workers' comp associated expenses as incurred.

A self-insured workers' comp plan is one in which the employer has legal approval from the one or more states to assume the financial risk for providing workers' comp benefits to its employees. In practical terms, self-insured employers pay the cost of each claim "out of pocket" as necessary. The employer maintains its ability to settle or adjudicate each claim within its self-insured retention – assuming it has excess insurance.

Importantly, key decisions, including which vendors to use to treat injured workers and to administer claims, remain with the employer and not an insurer.

How many employers currently operate a self-insured workers' comp program?

It is estimated that more than 6,000 corporations and their subsidiaries nationwide operate self-insured workers' comp programs. Many other smaller employers participate in Self-Insured Groups (SIGs), where they pool their risks with other companies.

How large do you have to be to self-insure?

Each state sets its own minimum standards for eligibility. For example, in California, you only need to have at least $5 million in shareholder equity and a net profit of $500,000 per year for the last five years. Eligibility is not based on the number of claims.

Keep in mind that each state is a distinct entity, so a company might be self-insured in one state where it has a high concentration of employees and have a large-deductible policy in another state with fewer employees.

Does the state require collateralization?

Every state, except California and North Carolina, has mandatory minimum security deposits that consist of: letters of credit, surety bonds, securities or cash. In many states, the amount posted by the self-insured is less that that required by an insurer or captive.

Can self-insured employers protect themselves against unpredicted or catastrophic claims?

Most states, except California, require self-insureds to purchase statutory (no limit) excess insurance from a state-licensed workers' comp insurer. Where available, a negotiated, aggregate stop-loss ("attachment point") endorsement protects an employer to a specific policy period dollar cap regardless of the per-claim self-insured retention or number of claims incurred.

Is self-insurance typically only used by large entities?

No. Employers of all sizes typically choose to self-insure because it gives them the greatest opportunity of any workers' comp funding alternative to manage their own destiny. A self-insured can control its costs by choosing and managing various program vendors and by implementing a wide variety of loss-prevention and return-to-work programs that serve to greatly reduce workers' comp claims. Self-insureds choose program components that they feel are the most cost-effective and responsive.

Who administers claims for self-insured workers' compensation programs?

Self-insured employers can either administer the claims in-house (if allowed by the state) or subcontract to a TPA. Other medical treatment or claim-related services can be "unbundled," or obtained through TPA contractual services.

- Opting Out of Workers Comp

The opt-out concept is appealing to those who believe that statutory workers' comp systems are hopelessly complicated, burdensome to both employers and their injured employees and out of touch. Privatized opt-out programs are intended to better integrate into the matrix of existing employee health plans and benefits.

Just two states have laws that allow employers to opt out of the state-regulated system: Texas and Oklahoma. Texas has always had this law, with 114,000 employers (about 1/3 of the total employers) choosing to forgo workers' comp coverage. Oklahoma recently adopted a variation where employers can choose an alternative to workers' comp coverage.

Practically speaking, "Opt-Out" ("non-subscription") gives employers enormous discretion to decide under what circumstances to compensate an injured worker under the employer’s own benefit plan. To protect the employer from most negligence lawsuits, as a condition of employment the employer can force the employee to sign a contract so all cases are resolved through an employer-designed, secret arbitration system rather than in court.

One crucial aspect is the adoption of federal standards under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) for administering work-injury benefits. A state insurance or self-insured guarantee fund would not back up an opt-out employer that defaults.

With continuing legal challenges to workers' compensation, including recent lawsuits against Uber and Lyft seeking court approval to mandate workers' compensation benefits for "app assigned" work, traditional workers' comp may give way to modern versions of the opt-out programs. The goal would be to create a more seamless benefit program that participants hope will take out the litigation components that have haunted the "no-fault compensation bargain" that began just more than 100 years ago.

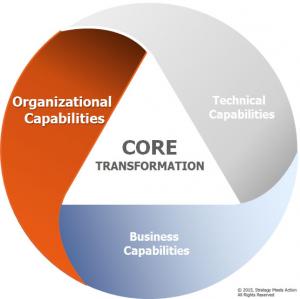

There is a happy ending to "Singing in the Rain," and it is not through the solution that Jean Hagen’s studio recommends – that being traditional diction training. Jean finds that what she does best, using her unique voice, leads her down the road to success in the new world of the talkies. In the transformative new world, insurers can also find their own road to success, heading toward the ultimate goal of becoming a Next-Gen Insurer. Core transformation, with its combination of synergistic organizational, business and technical capabilities, is a key ingredient to getting there.

There is a happy ending to "Singing in the Rain," and it is not through the solution that Jean Hagen’s studio recommends – that being traditional diction training. Jean finds that what she does best, using her unique voice, leads her down the road to success in the new world of the talkies. In the transformative new world, insurers can also find their own road to success, heading toward the ultimate goal of becoming a Next-Gen Insurer. Core transformation, with its combination of synergistic organizational, business and technical capabilities, is a key ingredient to getting there.

You Really Got a Hold on Me

In a time not so long ago, musicians had no choice but to go through record labels to even think about reaching their audience. The industry had a three-step process:

You Really Got a Hold on Me

In a time not so long ago, musicians had no choice but to go through record labels to even think about reaching their audience. The industry had a three-step process: