Data Breach Law Could Hurt Consumers

A data breach law making its way through Congress is designed to help but underscores a dangerous misunderstanding.

A data breach law making its way through Congress is designed to help but underscores a dangerous misunderstanding.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

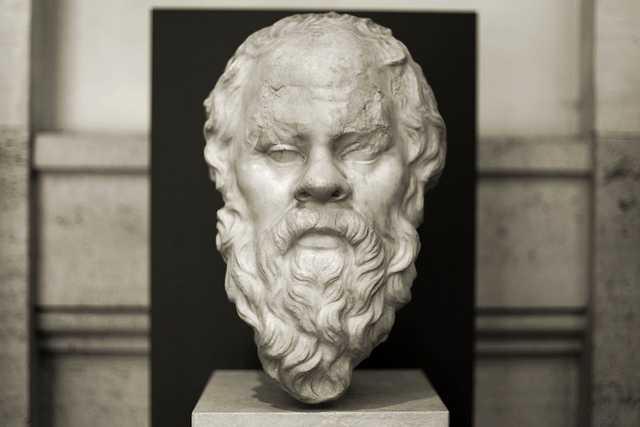

Far too often, what internal customers request from Customer Insight isn't what they really want or need. Socrates can help.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Paul Laughlin is the founder of Laughlin Consultancy, which helps companies generate sustainable value from their customer insight. This includes growing their bottom line, improving customer retention and demonstrating to regulators that they treat customers fairly.

Driverless cars will have to choose between evils when an accident is imminent, posing thorny ethics issues for makers and for insurers.

Self-driving cars will transform personal travel and, in doing so, will pose some interesting questions for insurers. One question that insurers seem not to have addressed so far involves the ethical issues raised by self-driving cars. And there's one particular issue of ethics that could have a significant influence on the liability exposures presented by self-driving cars.

Picture yourself relaxing back in a self-driving car. You've just dropped off your son, who has run off along the pavement ahead of you. Your car pulls out and accelerates, but suddenly six cyclists swerve into its path. A collision is imminent, and your self-driving car's computer has to make a split-second decision. Should the car swerve out of the way of the cyclists, saving their lives, but in doing so mount the pavement and kill your son? Or should it carry on and plow into the cyclists, saving your son's life?

Remember that the decision isn't yours: It's to be taken by your self-driving car's computer. Should the computer be programmed to reduce the overall number of casualties (and so avoid the cyclists but kill your son), or should it be programmed to put your interests first (and so collide with the cyclists)?

Classic ethical scenario

Some of you will recognize this as one of the classic scenarios used to stir debate in philosophy and ethics. It illustrates two ethical positions: utilitarianism and deontology. The former would say to swerve, for six lives are saved at the cost of one. The latter would say "carry on," for your interests are being put first.

The purely financial implications for insurers are clear: A self-driving car programmed according to utilitarian ethics will carry a lower liability exposure than one programmed according to deontological ethics. Will we see insurers turning to philosophers for help in deciding which car models fall into which rating categories?

Programmed by humans

The key point here, though, is not the employment prospects of philosophers but the recognition that all those algorithms underpinning the decisions made by self-driving cars will be programmed by human beings. Just like you and me, they'll be full of opinions and preconceptions, which will in turn influence the preferences coded into the decisions your self-driving car will take.

And as the big data supporting those decisions builds, so will the complexities that those algorithms have to handle. For example, if the six cyclists were wearing health tracking devices that told your self-driving car's computer that they were all octogenarians, should it still swerve into the path of your only child?

Embedding choices

The permutations are endless, but one dimension is fixed. It is that insurers using big data for underwriting and claims decisions need to recognize that choices are going to be embedded into those algorithms, and those choices often have an ethical dimension that needs to reflect the values of that insurer and the needs of the regulatory framework it operates within. Simply saying, as some insurers now do, that "it was the data that made the decision" will not hold water.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Duncan Minty is an independent ethics consultant with a particular interest in the insurance sector. Minty is a chartered insurance practitioner and the author of ethics courses and guidance papers for the Chartered Insurance Institute.

The appeals court's long-awaited decision is a knockout blow that lets the California legislature stop lien litigation madness.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit has issued its long-awaited decision in the Angelotti Chiropractic Inc. v Baker case. In what can only be considered a resounding win for both the legislature’s power to create the workers' compensation system and the Department of Industrial Relation's authority to enforce the provisions of SB 863, the appeals court has, in its 32-page decision, upheld the portions of the lower court's decision that were favorable to the DIR and reversed the portion that had challenged the validity of the statutory scheme. The result is a knockout, but not necessarily final, victory for the legislature and employer community's efforts to rein in lien litigation madness.

One of the hallmarks of the most recent reforms to the worker's compensation system in SB 863 was the adoption of both lien filing and lien activation fees. The intent of the fees was to filter out some of the less valid liens, encourage realistic settlement of liens before litigation and ultimately reduce the backlog of pending liens. Under the structure legislatively created, liens filed before Jan. 1, 2013, (the effective date of the statute) would be subject to an "activation fee" of $100 to actively pursue the lien before the W.C.A.B. Additionally, all pending liens as of Jan. 1, 2013, were required to have paid an activation fee by Jan. 1, 2014, or else be dismissed by operation of law. The second prong of the effort to reduce the backlog was to require lien claimants filing after Jan. 1, 2013, to pay a $150 filing fee. The challenge in this case was to the lien activation fee only, but the case has been watched carefully as similar arguments have been made in opposition to the lien filing fee. For many, Angelotti was considered a bellwether case on the lien fee validity.

Not surprising, shortly after its passage, the issue of the validity of the lien fee provisions in SB 863 was attacked in court with various challenges. In a ruling with what appeared to have the most potential for the challengers, a lower court had previously ruled that the plaintiffs in the Angelotti litigation had demonstrated a substantial likelihood of prevailing in their efforts to have the lien activation fee provisions declared unconstitutional. While by no means final, the resulting decision was accompanied by a temporary restraining order prohibiting the DIR from enforcing the lien activation fee provision. In its decision, the lower court rejected some of the plaintiff's arguments that the lien activation fee violated constitutional prohibitions under the takings clause and the due process clauses of the U.S. Constitution. That part of the claim was dismissed. The lower court, however, was much more impressed with the equal protection arguments advanced by the plaintiffs, finding that the different treatment of institutional lien claimants vs. direct medical providers did not constitute a rational distinction. As a result of the temporary injunction, the DWC suspended its enforcement of the lien activation fee provisions but appealed the ruling.

In its decision, the appeals court upheld the district court's rulings dismissing the plaintiff's causes of action based on the takings and due process arguments, finding that the lower court's rationale was well-founded. (The dismissal of those issues had been sought by the Angelotti plaintiffs.) However, in response to the defendant’s appeal of the restraining order and the failure to dismiss the equal protection claim, the court soundly rejected the lower court’s ruling that plaintiffs had established a probability of prevailing on an equal protection argument, reversing that holding and vacating the existing restraining order prohibiting the DIR from enforcing the lien activation fee provisions. That argument was based on the different treatment between institutional lien claimants (such as insurance companies) and private lien claimants (such as individual practitioners).

In reversing the lower court, the circuit court found the distinctions created by the legislature were both rational and within the wide latitude of the legislature to create:

"The legislature's approach also is consistent with the principle that 'the legislature must be allowed leeway to approach a perceived problem incrementally.' Beach Commc'ns, 508 U.S. at 316; see also Silver v. Silver, 280 U.S. 117, 124 (1929) (stating that '[i]t is enough that the present statute strikes at the evil where it is felt and reaches the class of cases where it most frequently occurs.'). Targeting the biggest contributors to the backlog-an approach that is both incremental, see Beach Commc'ns, 508 U.S. at 316, and focused on the group that “most frequently” files liens, see Silver, 280 U.S. at 124,-is certainly rationally related to a legitimate policy goal. Therefore, on this record, 'the relationship of the classification to [the Legislature's] goal is not so attenuated as to render the distinction arbitrary or irrational.'"

The appellate court further noted it was the plaintiff's burden to negate "every conceivable basis" that might have supported the distinction between exempt and non-exempt entities. The circuit (appellate) court said the district court did not put the plaintiffs to the proper test in this regard, instead rejecting the argument made by the defendants (DIR) that the activation fee was aimed at clearing up a backlog of liens. The circuit court found multiple flaws with the lower court’s analysis on this argument, including that it failed to give proper deference to the legislature's fact finding. Instead, the court held the proper application of correct legal principles demonstrated the plaintiffs, rather than showing a likelihood of success, actually showed no chance of success:

"...that plaintiffs have no chance of success on the merits because, regardless of what facts plaintiffs might prove during the course of litigation, 'a legislative choice is not subject to courtroom fact-finding and may be based on rational speculation unsupported by evidence or empirical data.' See Beach Commc'ns, 508 U.S. at 315. Thus, the presence in the commission report of evidence suggesting that non-exempt entities are the biggest contributors to the backlog is sufficient to eliminate any chance of plaintiffs succeeding on the merits."

While the plaintiffs in this matter have further appeal rights, it does not appear that under this decision the plaintiffs will be entitled to a trial at the lower court. The court not only vacated the injunction but took the unusual step of reversing the trial court's denial of defendant's petition to dismiss the equal protection cause of action. As noted in the above quote, the legislative authority to fashion a remedy effectively eliminated any chance of plaintiff's prevailing.

Comments and Conclusions:

While the decision in this appeal took some time to come, the finality of the decision, and the tenor of the court's ruling, will undoubtedly be considered well worth the wait. By reversing the lower court's failure to dismiss the equal protection clause, the appellate court left very little opening for preservation of this lawsuit. While the plaintiffs can both ask for a rehearing and appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, those levels of appeal come with rapidly diminishing probability of success.

With the DIR no longer hamstrung by the restraining order, we can anticipate a rapid enforcement of the lien regulations requiring activation fees. What will be a fascinating sideshow to this will be what happens to the provisions of Labor Code § 4903.06(a)(5), the requirement to pay the activation fee on any pre-1/1/13 lien claim on or before 1/1/14, a date long since passed. The DWC stopped collecting activation fees pursuant to the now vacated restraining order shortly after the TRO issued. Interestingly the language on the W.C.A.B.’s website indicated lien claimants were not obligated to pay the activation fee to appear at a hearing or file a DOR. However, it makes no mention of the dismissal language in 4903.06.

It is highly likely that few if any lien claimants paid activation fees by 1/1/14. It also seems unlikely, though not necessarily impossible, that the DIR or W.C.A.B. will be able to enforce the dismissal by operation by law provisions without allowing some kind of grace period for lien claimants to comply with the activation fee requirement before lowering the boom on liens without such fees. Lien claimants are now in something of a no man's land with the faint hope that a further appeal may save them from the lien activation cost, but the compliance clock will probably be ticking, and once it stops the jig will be up on their liens.

It would certainly make sense for any current lien claimants, especially those who are set for hearings, to start looking into complying with the activation fee requirements. Showing up at the W.C.A.B. on a pre- 1/1/13 lien claim without having paid the activation fee may very well result in dismissal in the very near future. For defendants, with the TRO no longer in force, it is game on as far as activation fees are concerned. I intend to start raising the issue tomorrow…(or at least at my next hearing with a pre-1/1/13 lien claim).

On a side note, a similar case in state court, Chorn v Brown, was also recently decided in an unpublished decision. In that case, a lien claimant had challenged the lien statutes on both activation and lien filing fees. The case has been dismissed for lack of subject matter jurisdiction in the superior court. As a practical matter, the dismissal is really more of a procedural issue than a substantive one. The court of appeal noted the proper remedy for Chorn was to pursue a petition for writ of mandamus in the court of appeal, a step Chorn has actually initiated. However, a petition for writ of mandamus requires an appellate court to decide the issue has merit, a rather dubious proposition at this point. However, it is one more step to finally clearing up the DIR/DWC/W.C.A.B.'s authority to deal with the lien morass that, while somewhat abated in the past couple of years, continues to plague the system.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Richard (Jake) M. Jacobsmeyer is a partner in the law firm of Shaw, Jacobsmeyer, Crain and Claffey, a statewide workers' compensation defense firm with seven offices in California. A certified specialist in workers' compensation since 1981, he has more than 18 years' experience representing injured workers, employers and insurance carriers before California's Workers' Compensation Appeals Board.

Was the ACA software designed primarily for benefits administration? (That will cost you.) Are forms stored for later use? (They'd better be.)

If you are a large employer or employee benefit broker, chances are you have spent a lot of time trying to determine the best ACA 6056 reporting and compliance solution. At ACA Reporting Service, we do not sell software - rather, full-service reporting. However, we have researched almost a dozen different Affordable Care Act employer reporting and compliance vendors, and we thought we would pass along what we learned.

Beginning Questions to Ask Yourself

As an employer or benefit broker, this is how the ACA software question breaks down for you.

1). Some employers will have their online enrollment (benefits administration) and payroll with the same vendor. In those cases, as long as the client is willing to pay for it, it will likely to make sense to just perform this required ACA reporting of IRS forms 1094 and 1095 with that vendor.

2). Some employers will not have an outside benefits administration vendor or payroll. They do everything in-house. For these employers, there is going to be a lot of ACA work to be done, and obviously you will need a stand-alone solution.

3). Finally, you have some employers that have payroll and benefits administration with different vendors. This would include the scenario where one of these functions is performed in-house. In these cases, you will either need to consolidate both payroll and benefit plan elections with one vendor, or you will need a stand-alone solution.

Basic conclusion: If you are an employee benefit broker with various types of employer clients, we don’t see a scenario where you can get away without having a stand-alone ACA software solution to help your clients meet their 6056 Affordable Care Act employer reporting requirements.

What do you need to know in evaluating ACA stand-alone software vendors? Here are some questions to ask yourself:

1). Security? What if all the Social Security numbers of your client's employees were stolen? Can you imagine the fallout? Many of the systems we reviewed were severely lacking in terms of security. What level of encryption is being used for the data?

2). Branded to your company? Many different ACA reporting vendors offer the ability to brand a portal to your company and let your employer clients log in.

3). Is the system mainly a benefits administration system? This can make an extreme difference. Will this add costs for the ACA reporting module? Also, with many benefits administration systems, there are additional charges for EDI (electronic data interface - where election data is sent to insurance carriers). Will additional fees apply with this new ACA reporting?

4). Is the ACA reporting solution even built yet? Many, MANY of the ACA reporting module demos we sat in on were from vendors that do not even have the software built yet.

5). How long will your data be stored? The IRS has said that audits will begin starting in about 18 months of filings, and that can last for 7 years total. If you do not have a methodology to get back to your data at the time of inquiry, you are stuck.

6). Is your vendor set up to file with the IRS? Did they just lie to you and say yes to that question? As of the writing of this blog, no one is set up to file with the IRS electronically (efile) for forms 1094 and 1095. The IRS has literally just issued the guidelines to begin getting started with this.

7). Variable hour tracking? Do you need variable hour tracking to determine eligibility? For many employers, a simple spreadsheet will do the trick. Many vendors have quite robust capabilities in this area, and for some employers this will definitely make sense.

8). The "Gotcha Moment." This comes at the end of a great presentation when you're told there is an additional charge of $3 to $5 per employee to file the forms with the IRS. Generally, these costs will render noncompetitive whatever solution you were just shown.

9). Robust ACA logic? We cannot tell you how important this is! If you have spent as much time looking at these forms as we have (especially in terms of form 1095c lines 14, 15 and 16), you will know that performing this reporting is MUCH MORE than just uploading a spreadsheet. The codes for these lines are based on logic. Most systems do not have this logic built into their system, so it will be up to you as an employer or benefit broker to figure this out. For most employee benefit agencies, you can count on this little "bug" shutting down your operations in January.

What if you decide to just file them incorrectly? When your largest client has 100 employees bring them letters from the IRS, you will then realize this was a very bad idea.

Also, without robust logic built into the system, there will be no accommodation for situations such as someone terminating in November/December and then electing COBRA in January. The codes for these situations are different.

10). Are forms stored for future access and corrections? Bottom line - there are going to be issues with the reporting from time to time. Do you have the ability to go back into the system and create a new/corrected 1094 or 1095 form on behalf of the employee? Many systems that rely solely on a census upload would require you to basically start over to make this one fix. OR, your staff can just manually create one in .pdf, which will take a lot of time.

11). Do you have to pay for the whole system up front, or are there monthly options? Do you need to commit to multiple years with the software vendor? Do you have to pay continually for the solution or only once? Are there implementation costs? Are there separate fees for the IRS form file reporting and all other functions in the system?

12). Can the employee elections be uploaded via census, or do you need to type it all in?

13). Will the vendor have adequate customer support between Jan. 1 and Jan. 31 so that you can KNOW you will be able to get all the work done?

14). Do you want to just let the payroll vendor do the work for your client? Do you really want to recommend that your client have another function performed by someone who wants nothing more than to take your business away from you?

. . . OK, that is enough! We hope you find this helpful.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Mark Combs is the managing partner of Triune Private Capital, an investment advisory firm dedicated to asset management of individuals and retirement plans. In addition, Triune Private Capital serves as the managing partner for investments in Triune Hedge Fund.

Benefit plan coverages and employer liability exposures are much more favorable for injured workers than "opt-out" opponents suggest.

This is the second of eight parts. The first article in the series is here.

"Opt-out" advocates have taken time to understand how workers' compensation systems work, so it is fair to expect option opponents to take time to understand how options work. Sometimes, option myths are simply because of misunderstandings. Sometimes, they are outright lies in a desperate attempt to maintain the status quo for workers' compensation programs that are championed only by a subset of interested insurance carriers, regulators and trial lawyers.

Despite what some myths say, most (if not all) option programs:

Opponents also do their best to avoid the fact that opt-out programs:

Interested in learning more? Consider this public policy paper or FAQ on the Oklahoma Option. In-depth information is also available from many insurance carriers and third-party administrators with whom you likely already do business. Let me know if you need contacts, legal citations, actuarially credible data or other detail on any point above.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Bill Minick is the president of PartnerSource, a consulting firm that has helped deliver better benefits and improved outcomes for tens of thousands of injured workers and billions of dollars in economic development through "options" to workers' compensation over the past 20 years.

Workers comp fraud just isn't taken seriously enough, perhaps because it's hard for so many to see insurance companies as victims.

Fraud, when discussed in the context of workers' compensation, is an interesting thing that many can't seem to agree on. Some injured workers will tell you that there is virtually no such thing as workers comp fraud (except for all the fraud committed against them by the entire world -- insurers, employers, regulators, Starbucks baristas and assorted Disney characters). Workers will grudgingly admit that in the event workers comp fraud does exist at all, it is so inconsequential, so infinitesimal, that it doesn't even deserve the time of day. Some on the professional side seem to believe that any claim is a fraudulent one and that injured workers are "guilty until proven innocent." They view every claim through a suspicious microscope and look for any indicator that someone is trying to pull the wool over their eyes.

The reality is that workers comp fraud exists, both on the worker and employer side. Fraud represents the minority of cases, but its presence makes it ever more difficult for the legitimately injured to navigate the labyrinth of comp.

All I know is this: We are far, far too easy on fraud cases when they are caught.

Our CompNewsNetwork ran a story about a former California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation officer who pleaded no contest to felony workers' compensation insurance fraud. He had filed a workers' compensation claim alleging he had injured his foot while working in the prison. It appears, however, that he failed to disclose his participation in certain events and activities. Those activities included "a 50-mile hike over rugged terrain just three weeks after he reported being injured at work." They also included activities like rock climbing, snowshoeing and acting in two plays, with multiple performances. He also engaged in numerous extreme hikes in rugged mountainous terrain during the one year and two months he was off work collecting benefits. Not to be satisfied with just committing fraud, he apparently felt compelled to document the endeavor, making video recordings and taking photos of many of his hikes and other activities.

Now, here's the rub: He will be placed on probation and ordered to serve 150 days in county jail, with the sheriff’s work furlough program recommended. He will also be ordered to pay to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation and State Compensation Insurance Fund a stipulated restitution amount of $33,262.56, with an additional $10,453.68 in discretionary costs to be determined by the court at sentencing.

In what can be termed the "coup de grace" (or Coop Da Grass as it is pronounced in northern Florida), if he pays restitution in full, the charge will be reduced to a misdemeanor.

Really? You can steal $33,262.56 but have it classified as a misdemeanor if you give it back? Is that the way it also works for embezzlement? Armed robbery? Burglary? If you give it back, all (or most) will be forgiven? The recommended time in the sheriff's work furlough program is a nice touch, as well. Can he work as a corrections officer while on work furlough from jail? That would be a short commute.

I suppose that means he could supervise himself.

This isn't the only fraud story I've seen with what I consider ridiculously light punishment. The problem, in my humble opinion, is that workers' comp fraud is a crime, but all too often it is treated as a minor indiscretion; they weren't stealing, they just filed a less than truthful claim and let the system send them money while they played or worked for cash or did whatever floated their boat at the time. The fraud is almost treated as a victimless crime, as people find it difficult to view an insurance company as a victim.

Never mind that we all pay for fraud, whether it is a faking prison guard or an employer flashing a bogus certificate of insurance. There are even bigger victims of fraud. They would be the legitimately injured who endure all the extra scrutiny that the specter of fraud brings to the table. These would be the people who are questioned simply because the possibility exists, and who are often left to feel as if they somehow wronged society by getting injured in the first place.

Getting injured isn't criminal. Faking an injury, quite frankly, is, and we should not be afraid to treat those who do so as the felonious thieves they actually are. We need to be tough on workers' compensation fraud.

It is the only way we will eventually see less of it.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Bob Wilson is a founding partner, president and CEO of WorkersCompensation.com, based in Sarasota, Fla. He has presented at seminars and conferences on a variety of topics, related to both technology within the workers' compensation industry and bettering the workers' comp system through improved employee/employer relations and claims management techniques.

Instead of having data gathering and analytics strewn all over, there will be one location for warehousing and one central source for analytics.

Last week, we spoke about how analytics in the insurance organization has been growing up in different locations and that it will continue to be interesting to see how and where analytics grows into maturity. Click here if you missed that blog and you would like to catch up. Today, we're going to step into the future and look at the most likely scenario in most insurance organizations, with the caveat that this will be highly dependent upon carrier size, type, unique features, etc.

To look at the logical location of analytics central within the insurance organization, it will be helpful to understand who will be using and needing data analytics and business intelligence (BI) reporting and how frequently it will be needed. In most organizations, this will naturally require some sort of assessment, because data gathering and analytics are changing at a rapid rate, and, if there is no current oversight, a survey/report will be needed.

For our purposes here, I'm going to assume that, sooner or later, nearly every area of the insurance value chain is going to be a consumer of data analytics. When we discuss analytics with insurance organizations today, we operate under the notion that data and analytics systems should be built with the capability to plug into areas of the organization that aren't clamoring for analytics yet. Operations or human resources might be excellent examples. Both are areas that may one day be composed of analytics power-users but today are only flirting with the fringes of data analytics. In the case of human resources, it may be making some data-driven decisions today, but often it is supplied through health insurance payers or other areas where it is pre-analyzed. As analytic capabilities grow, staffing choices and HR communications will benefit from entirely new levels of observation and reporting.

Once we make the case that anyone in the insurance organization could be a candidate for using analytics, we can also assume that data sources and analytics may frequently overlap from department to department. To address efficiencies, security and tool use throughout the organization, it may make sense to create an analytics department that operates as a central hub serving all other areas.

Let's use an analogy. We're in the midst of summer, and tomatoes or cucumbers may be growing in some of our back yards. With most vining plants, one root produces multiple fruits, varying in their maturity dates. Provided they are pollinated properly (go, bees!), the one vine will give many good tomatoes at various locations along the vine.

This is roughly comparable to what may happen in many insurers. Functions under the chief data officer will be responsible for gathering, housing and securing reliable data. Imagine that function as the roots and the soil of the vining plant. The data organization will then deliver the data to the analytics organization...the main vine that will turn the data "food" into the analytics "fruit." The fruit is the business intelligence every area needs to run its portion of the business. If we want to carry the analogy one step further, we can also consider that the fruit contains the seeds of the next generation's growth. So the analytics organization is not only going to produce good fruit but will also offer to plant its intelligence in areas where the business wants to see new growth.

Instead of having data gathering and analytics strewn all over the insurance greenhouse, there will be one location for warehousing and one central source for analytics. It is going to require oversight by the chief actuary, the chief data officer and in all probability a chief analytics officer. The chief marketing officer and the entire C-level will be a part of determining how this new unit is built to ensure timely and effective service to the organization. The analytics team will represent a unified core that will need to balance business needs with departmental priorities. In some ways, it will look much like today's management team, only with one goal - transforming the organization to be data-driven while keeping information secure and flowing through an ever-improving analytics infrastructure.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

John Johansen is a senior vice president at Majesco. He leads the company's data strategy and business intelligence consulting practice areas. Johansen consults to the insurance industry on the effective use of advanced analytics, data warehousing, business intelligence and strategic application architectures.

"Conservative care" needs to supplant opioids in the treatment of chronic pain -- premiums would plunge and workers would benefit.

The workers' comp industry is burdened with perhaps 200,000 or more injured workers on long-term opioid treatment for chronic pain. Many more workers enter these ranks yearly. For 10 years, I have observed this awful misery slowly accumulate. But claims payers can do more to prevent new case and resolve "legacy" cases. It will require from them more commitment to best practice care and a lot more frank, open collaboration among themselves and with medical providers.

Conservative care is hugely under-exploited as an approach to prevent and resolve chronic pain among injured workers. Workers' compensation claims payers would not have paid so much for opioid treatment, failed surgeries and claims settlements had they adopted conservative care decades ago, when research support for this approach was already pretty strong. The failure to promote this approach cost the policyholders perhaps $100 billion in higher premiums and cost injured workers years of disability and, in some cases, funerals.

By conservative care, I refer to functional restoration programs, which came into existence in the 1970s or earlier. Cognitive behavioral therapy became established in the 1980s. Coaching, as a non-medical method of helping persons in pain, has been around forever but recently gained visibility as a scalable form of intervention. There's a lot of innovation going on, such as the PGAP program imported from Canada and a number of nerve-stimulation services such as Scrambler in New England.

Payers need to learn how to create conditions within which conservative care can prosper rather than repeatedly blossom only to die.

A friend prods me to use the term "evidence-based medicine." But "conservative care" is my choice for an umbrella term because it is easy to remember, though inexact.

A few years ago, I talked by phone with a senior medical case manager at a claims payer in Kentucky, an epicenter of opioid prescribing excesses, who had never heard of functional restoration programs. This reminded me of the Harvard professor who spent a year in Munich without ever hearing about Oktoberfest.

The long history of insurers includes many instances where they brought risk management solutions like conservative care to the market. The first modern evidence of that goes all the way back to London fire insurers in the late 17th century. Mutual insurance companies played an essential role in introducing automatic fire-suppressing sprinkler systems to American factories in the late 19th century.

In my special report published by WorkCompCentral, "We're Beating Back Opioids - Now What?", I propose that claims payers and selected medical providers collaborate for the purpose of better success in treatment. This is particularly valuable for conservative care. The collaborations would allow each party to act on its own but to pool information. Periodically, analysts will dig into the database to report on the group’s experience on outcomes and costs.

The healthcare community, sometimes with the explicit support of health insurers, engages in collaborations to improve health outcomes. A Health Affairs article in 2011 is titled, "How a Regional Collaborative of Hospitals and Physicians in Michigan Cut Costs and Improved the Quality of Care." The article addresses surgical collaborations, for instance:

The article concludes that "results from the Michigan initiative suggest that hospitals participating in regional collaborative improvement programs improve far more quickly than they can on their own. Practice variation across hospitals and surgeons creates innumerable "natural experiments" for identifying what works and what doesn't.

Elsewhere, collaborations among independent medical providers have been noted in asthma, diabetes, surgery and congestive heart failure.

Another analysis of collaborations commented that "real improvements [in treatment] are likely to occur if the range of professionals responsible for providing a particular service are brought together to share their different knowledge and experiences, agree what improvements they would like to see, test these in practice and jointly learn from their results.

Claims payers need to help this cross-fertilization happen. Hard as it may seem, they need to "own" the need to build conservative care resources in their markets. Physicians don't understand conservative care; referral patterns are not set; and the providers of conservative care are often under-resourced. Claims payers need to step up.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

ApplePay introduces important elements into the security of mobile payments but also creates opportunities that hackers are already probing.

ApplePay, the mobile payments service introduced by Apple in October 2014, could ultimately set the security and privacy benchmarks for digital wallets much higher.

Even so, the hunt for security holes and privacy gaps in Apple's new digital wallet has commenced. It won't take long for both white hat researchers and well-funded criminal hackers to uncover weaknesses that neither Apple nor its banking industry partners thought of.

Here's ThirdCertainty's breakdown of the security and privacy issues stirred by Apple's bold move into the digital wallet business.

ApplePay defined

Available on the iPhone 6 and Apple Watch, ApplePay stores account numbers on a dedicated chip. Apple refers to this chip as the "secure element" only available n the iPhone 6 and iPhone 6 plus. It is on this chip that your financial information is stored. It is only accessed when a random 16-digit number gets generated for a given transaction, and the number never makes it to the phone's software, where hackers could reach it.

The devices then use near field communication (NFC) to send a simple token, instead of the full account number, to the merchant’s NFC-enabled point-of-sale register.

"This allows an ultra secure payment," says Anthony Antolino, business development officer at Eyelock, a biometrics technology vendor. "The only remaining concern is keeping the smart phone under your control."

Apple tightens down who can control each device by integrating itsTouch ID fingerprint scanner and its Passbook ticket-buying app into ApplePay. This new approach keeps personal information on the device - instead of moving account data into storage servers within easy reach of thieves. The hacks of big merchants in the U.S. and Europe, including Home Depot, Target, P.F. Chang's and Neiman Marcus, show how adept data thieves have become at attacking stored data.

How ApplePay improves security

ApplePay validates a "data-centric security model," argues Mark Bower, product management vice president at Voltage Security.

"The payments world needs to move on from vulnerable static credit card numbers and magnetic stripes to protected versions of data," Bower says. "Tokenized payments reduce the risk of data breaches and credit card theft."

Mathew Rowley, technical director at security consultancy NCC Group, observes that the U.S. payment card industry continues to require minimal security checks in authorizing credit and debit card purchases.

“Things like chip-and-PIN and two-factor credit cards have been implemented in other countries, but the U.S. seems to be behind the curve,” Rowley says. “Any additional logic built into the process of making payments will make it more secure.”

How ApplePay introduces new risks

Adding a mobile wallet function to the latest iPhone gives criminal hackers more incentive and opportunity to find fresh vulnerabilities, says Mike Park, managing consultant at Trustwave.

"Any new additions and functionality to a platform, even ones meant to enhance security, can expand the attack surface," Park says. "With the introduction of this type of functionality into a platform, this makes every device a possible target."

The more popular ApplePay becomes, the more likely cybercriminals will devote resources to cracking in. Research from legit sources already is available showing how to hack into NFC systems -- for instance this 2012 report from Accuvant reseacher Charlie Miller.

It's probable that elite criminal hackers "are looking to steal identities and mass harvest payment card information as they do in other platforms and verticals now," Park says.

One simple crime would be to target Apple devices for physical theft. Another is to figure out how to remotely access and manipulate ApplePay accounts. "The weakest link is the consumer," says Alisdair Faulkner, chief products officer at ThreatMetrix. "And ultimately a web page with a username and login, like iCloud, now has an unprecedented amount of information about you backed up into the cloud."

Pushing payments to mobile devices makes Internet cloud services more complex - and complexity creates vulnerabilities.

"In the past, the only participants were the merchant, the merchant’s bank and your personal bank," says Richard Moulds, vice president of product strategy at Thales e-Security. "Apple is stating that they will not know the details of individual transactions, which is very important; however, there is clearly the risk of attacks on the phone itself."

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Byron Acohido is a business journalist who has been writing about cybersecurity and privacy since 2004, and currently blogs at LastWatchdog.com.