The follow-the-leader principle works on a trail that has proven to be relatively safe from perils and predators. However, when new frontiers are breached, a new kind of leadership is required for survival.

Insurers have generally been able to just follow the leader for ages, but now a new frontier has been breached. The insurance industry is vulnerable to three game changers that consumers are eager to embrace.

Drawing on remarks I made recently at a keynote for the National Association of Mutual Insurance Companies Annual Conference, here are the game changers:

The first big disrupter is data collection. Insurance is built on the principle of using accurate data and statistics to build underwriting financial models that serve to predict behavior and events from an actuarial or probability standpoint. London's Edward Lloyd figured this out when he opened his coffee shop in 1688, and people started selling insurance to merchants and ship owners. His motto was fidentia, Latin for confidence. We now refer to "confidence factors" when estimating future losses.

Insurers have been notorious for using forms to collect data. But, today, a person is subjected to more new information in one day than a person in the Middle Ages saw in his entire life. If modern competitors to the insurance industry can obtain more accurate data in a faster and more in-depth manner, they may beat insurers at their own game.

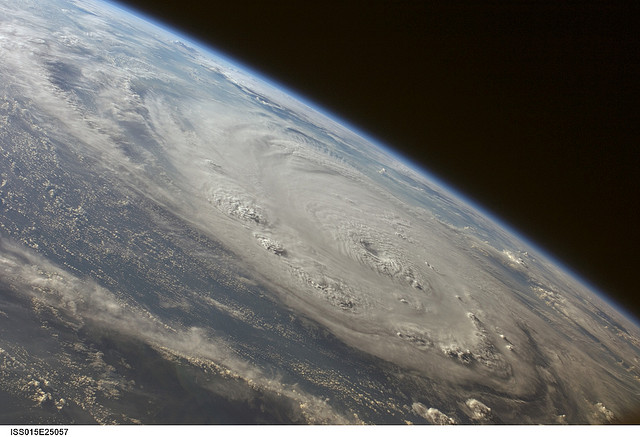

With cloud computing and its infinite data storage/retrieval capability, trillions of bits of information relating to insureds are available. Data sources track things like profile patterns, such as personal Internet searches or satellite surveillance data. Relevant data can be mined and analyzed to build a risk model for every insurable consumer or business peril from property and vehicle insurance to earthquake and weather insurance.

The five biggest data collectors on the planet are Google, Apple, Facebook, Yahoo and Amazon. These high-tech companies have the ability, financial resources and potential desire to foray into the insurance industry. Keep in mind that in 2014 the world's top 10 insurers received $1.2 trillion in revenue, yet surveys have shown that people around the world have grown to use and trust the products and services provided by the five biggest data collectors.

Accessibility and familiarity are allowing profitable new brands to replace old brands. Consumers also prefer and use third-party validation and independent comparisons found on websites.

What does this spell for the insurance industry? Sadly, consumers have grown more uncomfortable with reliance on and interaction with agent relationships. John Maynard Keynes once said: "The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas, as in escaping from old ones."

The second emerging threat to insurance is botsourcing -- the replacement of human jobs by robotics. The robots haven't just hatched in agriculture or auto assembly plants -- they're expanding in a variety of skills, moving up the corporate ladder, showing awesome productivity and retention rates and increasingly shoving aside their human counterparts.

Google won a patent recently to start building worker robots with personalities. Move over, Siri.

Author and entrepreneur Martin Ford, in his book Rise of the Robots, argues that artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics will soon overhaul our economy. Increasingly, machines will be able to take care of themselves, and fewer jobs will be necessary.

Reassessment of the way we employ our workforce is essential to cope with this new industrial revolution. The lucrative insurance realm of personal and product liability insurance lines and workers' comp is being tempered as human risk factors -- especially in high-risk areas -- give way to robotics. The saying goes: "Management is doing things right, but leadership is doing the right things."

How will the insurance industry react to the accelerating technology of bot-sourcing?

The third emerging threat to the insurance industry that has received enormous attention this past year autonomous vehicles. More than a half-dozen carmakers, as well as Google and Uber, predict that self-driving vehicles will be commonplace on our roads between 2017 and 2020. Tesla Motors CEO and general future-tech proponent Elon Musk has predicted that human drivers could someday be outlawed. Humans cannot outperform an autonomous vehicle, which can assess and react to more than 7,000 driving threats per second. There are no incidents of driver impairment, reckless driving, DUIs, road rage, driver texting, speeding or inattention.

With a plethora of electronic distractions, increased safety can only be achieved when human drivers are removed from the equation. Automakers have employed an incremental approach to safety in their current models. These new technologies are clever and helpful but do not remove the risks. There's a phenomenon called the Peltzman Effect, based on research from an economist at the University of Chicago who studied auto accidents. He found that, when you introduce more safety features like seatbelts into cars, the number of fatalities and injuries doesn't drop. The reason is that people compensate for it. When you have a safety net in place, people will naturally take more risks. Today, 35,000 vehicle occupants die in the U.S. because of auto accidents. Autonomous vehicles are expected to cut auto-related deaths and injuries by 80% or more.

One of the biggest revenue sources to insurers is vehicle insurance. As autonomous vehicles take over our roads and highways, you need to address all the numerous unanswered questions relating to the risk playing field. Who will own the vehicles? How can you assess the potential liability of software failure or cyberattacks? Will insurers still have a role? Where will legal liabilities fall? Who will lead the call to sort these issues out?

Clearly, the lucrative auto insurance market will change drastically. Insurance and reinsurance company leadership will be an essential ingredient to address this disruptive technology.

As I told the conference: Count on Insurance Thought Leadership to play a significant role in addressing these and other disruptive technologies facing the insurance industry. A Chinese proverb says: "Not the cry, but the flight of a wild duck, leads the flock to fly and follow."