What do you do if your entire industry has a negative ROI? If your industry and its lack of ROI have been skewered in the media? If even RAND, which is the most neutral, grownup organization in all of healthcare, now says your industry, wellness, produces no savings and no reduction in utilization of healthcare services? If your leadership group accidentally proved their own industry loses money for its customers? If, on this very site, Insurance Thought Leadership, your patron saint, Harvard professor Katherine Baicker, professes to have no interest in wellness any more, now that her work has been eviscerated?

What do you do if there is a proof that saving through wellness is impossible, and another proof that, even if savings were possible, there haven't been any? If these proofs are backed with a $1 million reward for anyone who can disprove them?

Here’s what you do: You change the rules so ROI doesn’t matter any more.

The new mantra is "value on investment," or VOI. The Willis Health and Productivity Survey published this week claims that 64% of employers do wellness for VOI - specifically, "employee morale" and "worksite productivity." (The survey also mentions "workplace safety." I guess the workplace is safer if no one is working because they are all out getting checkups.)

But the darnedest thing is, all the data shows that the best way to really get value on your investment is to cancel your "pry, poke, prod and punish" wellness program.

Employee Morale

Have you ever seen employees demand more blood tests? More Health Risk Assessments (HRAs)? More weigh-ins? Quite the opposite. This shouldn't be a newsflash, but employees hate wellness programs, except for the part where they get to collect employers' money. As a CEO myself (of Quizzify), I pride myself on our corporate culture. The last thing I would do is force my employees into a wellness program. It would destroy the camaraderie we've established.

Obviously, if employees liked wellness, you wouldn't need large and growing incentives/penalties to get people to participate. Employees dislike wellness programs so much that collectively they've forfeited billions of dollars just to avoid these programs.

Anecdotes often speak more loudly than data, and employee morale anecdotes are easy to come by. Simply look at the "comments" on quite literally any article in the lay media involving wellness programs. It's usually about 10-to-1 against wellness, with the "1" being someone who says: "Why should I pay for someone who's fat?" or something similar. Or the positive comment comes from a wellness vendor or consultant. You know an industry is bogus when the only people who defend it are people who profit on it.

The weight-shaming involved in wellness programs is, of course, a huge fallacy. Among other things, except at both extremes, there is only a slight correlation between weight and health expense in the under-65 population -- the problems associated with weight show up later, typically after people leave the workforce. Assuming major differences among employees would lead to underwriting every individual-marathoners who might get injured, women who might get pregnant, etc. Take the fallacy out, and there is nothing that the American public-left, right and center - is more unified on than detesting wellness.

Workplace Productivity

You're already pulling people off the line to do the "pry, poke and prod" programs and send them for checkups that are more likely to harm employees than benefit them. So productivity takes a hit to begin with. Add to that the weight-shaming and ineffectiveness of corporate weight-loss programs.

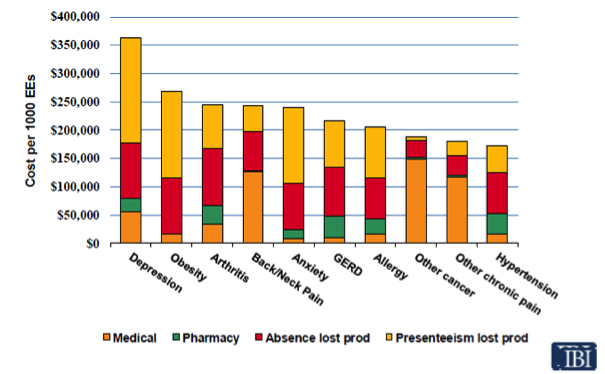

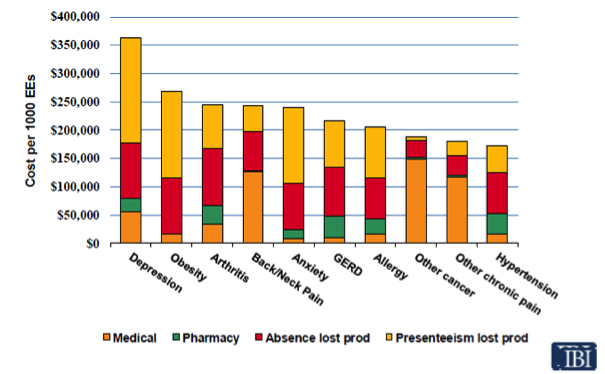

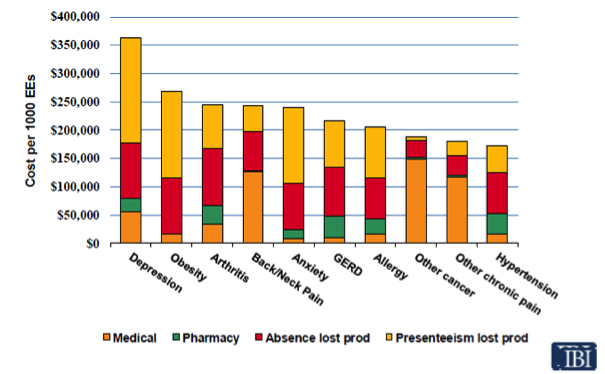

Most importantly, it turns out - according to the Integrated Benefits Institute, a wellness industry association - that the major contributor to low productivity is depression:

Maybe this is just me, but if I were running a company where workers were depressed, I probably wouldn't try to address depression by implementing a program that workers were going to hate, which is sort of a "the beatings will continue until morale improves" approach to management. I'm just sayin'...

The other noteworthy observation? Anxiety has a big impact on productivity. Wellness programs pride themselves on how many diseases they find. This practice is called hyperdiagnosis. The goal is to scare as many employees as possible into thinking they're sick. The C. Everett Koop-award-winning Nebraska state wellness program, for example, bragged about how it found that 40% of employees were at risk. However, the program didn't do anything about the finding, and a year later only 161 employees in the entire state had reduced a risk factor. The vendor, Health Fitness Corporation, also bragged about all the cancer cases it found and all the lives it saved, until admitting the whole thing was made up.

Once again, it's not clear how a wellness program would reduce anxiety and increase productivity. Or maybe I'm wrong. Maybe there's nothing like being told you are at risk of dying to really focus you on clearing your inbox before you croak.

Conclusion

Pretending there is a VOI looks to be even sillier than pretending there is an ROI, because wellness neither increases morale nor improves productivity.

All of this brings us back to what we've been saying for years-especially on this site, which was willing to post our stuff long before it was popular to do so: Do wellness for your employees and not to them.

The latter doesn't work no matter what initials you use. But if you want to improve morale and productivity, up your game for perks, subsidize healthier options for food and maybe even directly subsidize a portion of gym memberships. And maybe teach your employees how to spend their healthcare dollars more wisely. (Disclosure: That is the business we are in.)

What do you do if your entire industry has a negative ROI? If your industry and its lack of ROI have been skewered in the media? If even RAND, which is the most neutral, grownup organization in all of healthcare, now says your industry, wellness, produces no savings and no reduction in utilization of healthcare services? If your leadership group accidentally proved their own industry loses money for its customers? If, on this very site, Insurance Thought Leadership, your patron saint, Harvard professor Katherine Baicker, professes to have no interest in wellness any more, now that her work has been eviscerated?

What do you do if there is a proof that saving through wellness is impossible, and another proof that, even if savings were possible, there haven't been any? If these proofs are backed with a $1 million reward for anyone who can disprove them?

Here's what you do: You change the rules so ROI doesn't matter any more.

The new mantra is "value on investment," or VOI. The Willis Health and Productivity Survey published this week claims that 64% of employers do wellness for VOI - specifically, "employee morale" and "worksite productivity." (The survey also mentions "workplace safety." I guess the workplace is safer if no one is working because they are all out getting checkups.)

But the darnedest thing is, all the data shows that the best way to really get value on your investment is to cancel your "pry, poke, prod and punish" wellness program.

Employee Morale

Have you ever seen employees demand more blood tests? More Health Risk Assessments (HRAs)? More weigh-ins? Quite the opposite. This shouldn't be a newsflash, but employees hate wellness programs, except for the part where they get to collect employers' money. As a CEO myself (of Quizzify), I pride myself on our corporate culture. The last thing I would do is force my employees into a wellness program. It would destroy the camaraderie we've established.

Obviously, if employees liked wellness, you wouldn't need large and growing incentives/penalties to get people to participate. Employees dislike wellness programs so much that collectively they've forfeited billions of dollars just to avoid these programs.

Anecdotes often speak more loudly than data, and employee morale anecdotes are easy to come by. Simply look at the "comments" on quite literally any article in the lay media involving wellness programs. It's usually about 10-to-1 against wellness, with the "1" being someone who says: "Why should I pay for someone who's fat?" or something similar. Or the positive comment comes from a wellness vendor or consultant. You know an industry is bogus when the only people who defend it are people who profit on it.

The weight-shaming involved in wellness programs is, of course, a huge fallacy. Among other things, except at both extremes, there is only a slight correlation between weight and health expense in the under-65 population -- the problems associated with weight show up later, typically after people leave the workforce. Assuming major differences among employees would lead to underwriting every individual-marathoners who might get injured, women who might get pregnant, etc. Take the fallacy out, and there is nothing that the American public-left, right and center - is more unified on than detesting wellness.

Workplace Productivity

You're already pulling people off the line to do the "pry, poke and prod" programs and send them for checkups that are more likely to harm employees than benefit them. So productivity takes a hit to begin with. Add to that the weight-shaming and ineffectiveness of corporate weight-loss programs.

Most importantly, it turns out - according to the Integrated Benefits Institute, a wellness industry association - that the major contributor to low productivity is depression:

Maybe this is just me, but if I were running a company where workers were depressed, I probably wouldn't try to address depression by implementing a program that workers were going to hate, which is sort of a "the beatings will continue until morale improves" approach to management. I'm just sayin'...

The other noteworthy observation? Anxiety has a big impact on productivity. Wellness programs pride themselves on how many diseases they find. This practice is called hyperdiagnosis. The goal is to scare as many employees as possible into thinking they're sick. The C. Everett Koop-award-winning Nebraska state wellness program, for example, bragged about how it found that 40% of employees were at risk. However, the program didn't do anything about the finding, and a year later only 161 employees in the entire state had reduced a risk factor. The vendor, Health Fitness Corporation, also bragged about all the cancer cases it found and all the lives it saved, until admitting the whole thing was made up.

Once again, it's not clear how a wellness program would reduce anxiety and increase productivity. Or maybe I'm wrong. Maybe there's nothing like being told you are at risk of dying to really focus you on clearing your inbox before you croak.

Conclusion

Pretending there is a VOI looks to be even sillier than pretending there is an ROI, because wellness neither increases morale nor improves productivity.

All of this brings us back to what we've been saying for years-especially on this site, which was willing to post our stuff long before it was popular to do so: Do wellness for your employees and not to them.

The latter doesn't work no matter what initials you use. But if you want to improve morale and productivity, up your game for perks, subsidize healthier options for food and maybe even directly subsidize a portion of gym memberships. And maybe teach your employees how to spend their healthcare dollars more wisely. (Disclosure: That is the business we are in.)