Over the past decade, many industries have made tremendous progress when it comes to offering consumer choice. Just look at the travel industry. Twenty years ago, it wasn’t possible to search for a flight, compare dozens of different options side-by-side and tailor your selection to match your specific needs. Shopping experiences across many categories are now offering choices -- and making those choices clear. The healthcare industry, however, is lagging behind. And when it comes to something as critical as healthcare, clear choices are

imperative. Consumers who make a less-than-optimum insurance choice face higher costs, less satisfaction and poorer health when an issue that should be looked after gets ignored because it’s not covered.

These Six Factors Make Clear Choices Imperative for Health Insurance Shoppers

1. Cost

When most individuals shop for a new plan, it’s not just a matter of going with the option that comes with the lowest monthly premium. There’s always a juggling act between the monthly premium and out-of-pocket costs. If the co-pays and deductibles are too high, if there are services that individuals use that aren’t covered, the lowest-cost plan may well end up costing the consumer more. Consumers need to understand their total cost of healthcare with any given plan.

See also: Key Misconceptions on Health Insurance

2. What’s Covered

After the basics, individuals may have a wide range of services for which they seek coverage, and every healthcare consumer will have different needs. One individual may require mental health services, another physical therapy. For yet another, it’s audiology services. Even if a certain service is covered at some level, there will likely be different limits (e.g., the number of physical therapy sessions allowed) from one plan to the next. While it’s not possible for individuals to anticipate everything that they might need in a year, consumers should be experts in their current requirements.

3. Prescription Drug Coverage

Formularies listing the prescription drugs covered under each insurance plan can be extensive. And when they’re on paper, they can be very difficult to navigate. However, consumers are quickly learning the importance of determining whether the drugs they take are covered by their health insurance plans. Given last year’s unexpected cost increases for the EpiPen, consumers are wising up. Looking through the formulary and not finding an expensive drug they need to take regularly may knock a plan out of consideration.

4. Provider Network

Whether a healthcare provider is in-network is a big deal to consumers. In fact, when it comes to choosing a physician, it may be the biggest deal. A 2015 survey of more than a thousand patients showed that 90% of consumers

reported that the most important attribute of a physician is whether they accept the individual’s health insurance – more important even than the physician’s clinical experience. Consumers need to know what happens when they see a physician or other provider, or use a hospital, that’s outside of their network: The costs may be untenable. Consumers might be okay with switching from a primary care physician to someone new if they only see them once a year for a regular physical. But if they’ve developed a close relationship with their pediatrician – someone they like and trust – they’ll want to make sure that their provider is in-network.

5. Unique Elements

Consumers are taking more ownership of their own healthcare. These days, when shopping for health insurance, they are now factoring in all of the details that make them unique. For example, if their kids play sports, they’re thinking about ER visits. When they’re planning an addition to the family, they’re doing research to see if the facility where they want to have their baby is covered by their health plan. There are many unique elements that require choice. Health insurance is not a one-size fits all solution.

6. Overall Risk Aversion

When it comes to choosing a health insurance plan, risk aversion is really about what level of financial risk an individual is able to accept. And, in this regard, every individual is different. The lower-cost premium plan might be fine if there’s a low probability of something occurring that is not covered. But if you’re likely to be making frequent ER trips with your kids, that low-premium plan may not be so attractive. It’s up to the individual to determine how risk-averse they are.

Insurance customers are desperate for clear choices that are easy to understand. They need them because everyone is unique and living a different situation. And, given the wide range of choices that are available to consumers in so many other aspects of their lives, they expect options. Choices provide an opportunity for your customers to find the best-fitting health insurance plan. Are you offering enough choices?

See also: The Basic Problem for Health Insurance

Clearly presenting the information that today’s healthcare consumers require can be overwhelming. After all, carriers are experts in insurance, not in software application development and data presentation. Fortunately, in the 21st century, data is highly digestible, usable and transparent. Health insurtech companies across the nation are making sure of that. As insurance carriers and health insurtech companies work together, slowly but surely, the industry will progress, offering more clearly defined choices for today’s consumers.

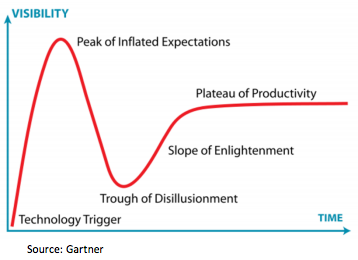

Have we reached the peak of inflated expectations? We expect not. Certainly, valuations continue to rise with relatively new businesses still at the effectively pre-revenue stage commanding valuations in the tens of millions. Hard to justify on any fundamental level.

However, at the core of insurtech, we continue to see a huge opportunity to innovate in a sector that is ripe for change – lack of customer engagement, lack of customer trust, outdated and legacy infrastructure combined with traditional and unpopular products all highlight the need for change and the underlying potential.

Ignore Insurtech at Your Own Risk

Eos has talked with dozens of insurance companies, and there is a wide range of responses from the insurance community about when, where, if and how to engage with insurtech.

The top insurance companies have, for the most part, followed a two-phased approach combining an innovation team with a corporate venture initiative. These carriers see the impending disruption clearly and want to be able to shape and influence the impact. The results so far have been mixed, as some large incumbents have found it difficult to circumvent legacy mindsets, governance, organizational structures and technology.

See also: 10 Trends at Heart of Insurtech Revolution

Other carriers have yet to agree/settle on an approach to deal with these disruptive forces.

Eos calculates that the impact of insurtech is at least 40% to the average carrier. We calculate that by looking at a 20% upside, and a 20% downside scenario:

On a conservative basis, insurers may risk losing at least 20% of their business to disruption. On the flip side, for those that embrace innovation there is an opportunity to grow their business by 20%.

Stated another way, the net present value (NPV) of insurtech is $100 million for every $1 billion of premium on the downside and $285 million on the upside, assuming a top-line and profitability improvement.

Timing is also key, as the scale of adoption and impact is not linear. The upside opportunity by investing now in the right opportunities is likely to give an insurer a lead that others can’t catch --- essentially a “first-mover” advantage. At the same time, the lost opportunity by delaying is exponential, not linear.

There are many ways to create and capture value

The positive momentum is further driven by the growth of insurtech into all areas of the value chain and across multiple product lines. We see two broad types of innovator: the "enabler" and the "disruptor."

The enabler is a business that significantly improves an existing part of the value chain driving efficiency, improved customer satisfaction or better customer outcomes. A great example is RightIndem, which is transforming the claims process by creating an end-to-end, customer-managed claims process.

The disruptor is a business that has developed a new approach to fulfilling part, or all, of the value chain. This is illustrated by Insure A Thing, an insurtech startup that has created a way of providing insurance without the need for an upfront premium.

On face value, the disruptors may appear more exciting, but the enablers perhaps better illustrate the underlying potential of insurtech, as there are an abundance of opportunities for most insurance companies to hit "the low-hanging fruit" and do things better, more cheaply and more aligned with the customer.

Insurtech is not an overnight revolution, and there are many ways to create and capture value that combine different elements of the above, for example:

Have we reached the peak of inflated expectations? We expect not. Certainly, valuations continue to rise with relatively new businesses still at the effectively pre-revenue stage commanding valuations in the tens of millions. Hard to justify on any fundamental level.

However, at the core of insurtech, we continue to see a huge opportunity to innovate in a sector that is ripe for change – lack of customer engagement, lack of customer trust, outdated and legacy infrastructure combined with traditional and unpopular products all highlight the need for change and the underlying potential.

Ignore Insurtech at Your Own Risk

Eos has talked with dozens of insurance companies, and there is a wide range of responses from the insurance community about when, where, if and how to engage with insurtech.

The top insurance companies have, for the most part, followed a two-phased approach combining an innovation team with a corporate venture initiative. These carriers see the impending disruption clearly and want to be able to shape and influence the impact. The results so far have been mixed, as some large incumbents have found it difficult to circumvent legacy mindsets, governance, organizational structures and technology.

See also: 10 Trends at Heart of Insurtech Revolution

Other carriers have yet to agree/settle on an approach to deal with these disruptive forces.

Eos calculates that the impact of insurtech is at least 40% to the average carrier. We calculate that by looking at a 20% upside, and a 20% downside scenario:

On a conservative basis, insurers may risk losing at least 20% of their business to disruption. On the flip side, for those that embrace innovation there is an opportunity to grow their business by 20%.

Stated another way, the net present value (NPV) of insurtech is $100 million for every $1 billion of premium on the downside and $285 million on the upside, assuming a top-line and profitability improvement.

Timing is also key, as the scale of adoption and impact is not linear. The upside opportunity by investing now in the right opportunities is likely to give an insurer a lead that others can’t catch --- essentially a “first-mover” advantage. At the same time, the lost opportunity by delaying is exponential, not linear.

There are many ways to create and capture value

The positive momentum is further driven by the growth of insurtech into all areas of the value chain and across multiple product lines. We see two broad types of innovator: the "enabler" and the "disruptor."

The enabler is a business that significantly improves an existing part of the value chain driving efficiency, improved customer satisfaction or better customer outcomes. A great example is RightIndem, which is transforming the claims process by creating an end-to-end, customer-managed claims process.

The disruptor is a business that has developed a new approach to fulfilling part, or all, of the value chain. This is illustrated by Insure A Thing, an insurtech startup that has created a way of providing insurance without the need for an upfront premium.

On face value, the disruptors may appear more exciting, but the enablers perhaps better illustrate the underlying potential of insurtech, as there are an abundance of opportunities for most insurance companies to hit "the low-hanging fruit" and do things better, more cheaply and more aligned with the customer.

Insurtech is not an overnight revolution, and there are many ways to create and capture value that combine different elements of the above, for example: