How to Avoid Summer Scams

As the weather gets warmer, mosquitos and ticks re-enter our lives, and along with them comes their larger cousin, the scam artist.

As the weather gets warmer, mosquitos and ticks re-enter our lives, and along with them comes their larger cousin, the scam artist.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Adam K. Levin is a consumer advocate and a nationally recognized expert on security, privacy, identity theft, fraud, and personal finance. A former director of the New Jersey Division of Consumer Affairs, Levin is chairman and founder of IDT911 (Identity Theft 911) and chairman and co-founder of Credit.com .

CFOs have limited awareness of the unnecessary risks and poor strategies deployed by the people they think are managing their healthcare spending.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Craig Lack is "the most effective consultant you've never heard of," according to Inc. magazine. He consults nationwide with C-suites and independent healthcare broker consultants to eliminate employee out-of-pocket expenses, predictably lower healthcare claims and drive substantial revenue.

Last week, Mary Meeker released her annual opus on the state of the digital world, and I wanted to be sure you saw it. Her massive, 355-slide deck is now the bible about the state of the internet for the next year, so you'll be seeing some of the data a lot. You should also spend some time with the presentation because some of the trends will matter a lot for insurance.

Beyond what you'd expect about the continued growth of the internet and about our obsessions with our mobile phones, three things stood out for me.

First is the continued improvement of voice recognition. Slide 48 says the technology is now roughly as accurate as we humans are. That still leaves room on the back end for figuring out how to turn those words into a query that can hit a data base and get a useful response—try asking your Amazon Echo what the leading cause of car accidents is—but the progress means we all have to keep working to incorporate voice recognition into interactions with customers. Just when you thought that moving to chatbots and texting put you on the cutting edge, you're getting another technology thrown at you.

Second is that apps are fading as the organizing principle for mobile devices. As slick as apps seemed to almost all of us at one point, it seems they're now just too cumbersome. Now, the trend is to make things happen "in-app"—inside whatever app someone is using. Slide 70, for instance, shows capability built by Google inside the Lowe's app that leads people in a Lowe's store to an item they're trying to find. I first asked a friend, the CIO of a regional grocery store chain, for that sort of capability more than a decade ago, and I'm reminded of that request every Mother's Day when I try to find where a store has hidden the tiny yellow cans of Hollandaise sauce that I need for Eggs Benedict. I'm delighted that my wait is ending. More importantly, from an insurance standpoint, the move toward in-app capabilities creates both a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge is that you have to move beyond the boundaries of your own app and establish a presence in whatever app your customer is using. The opportunity is for what might be called a do-you-want-fries-with-that strategy: "I see that you're heading toward the chainsaws at Lowe's; do you want some additional insurance to cover yourself and your house, for whatever happens when you take that tree down?"

Third is that the trends that Meeker identifies create liabilities that insurers need to consider and risks that they can cover. Some of the issues that she discusses at length will be familiar, such as the growing cyber risks that come with our increasingly connected world and the increasing, but still quite limited, health information from wearables. I'm more intrigued by some of the smaller examples she provides. For instance, Slide 66 says that apartment lobbies are becoming warehouses because of all the package deliveries and that the landlord/super is becoming the foreman of those warehouses. Sounds like a risk that the insurer should be aware of and possibly sell additional insurance to cover.

Happy exploring!

Cheers,

Paul Carroll,

Editor-in-Chief

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Paul Carroll is the editor-in-chief of Insurance Thought Leadership.

He is also co-author of A Brief History of a Perfect Future: Inventing the Future We Can Proudly Leave Our Kids by 2050 and Billion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn From the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last 25 Years and the author of a best-seller on IBM, published in 1993.

Carroll spent 17 years at the Wall Street Journal as an editor and reporter; he was nominated twice for the Pulitzer Prize. He later was a finalist for a National Magazine Award.

Technology advancements are blurring the borders between humans and machines. Where is this all leading us?

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Sri Ramaswamy is the founder and CEO of Infinilytics, a technology company offering AI and big data analytics solutions for the insurance industry. As an entrepreneur at the age of 19, she made a brand new product category a huge success in the Indian marketplace.

Why can’t insurance work in the same way as Amazon, easy, seamless, one-click, no hassle, managed through your mobile and regular updates?

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Sam Evans is founder and general partner of Eos Venture Partners. Evans founded Eos in 2016. Prior to that, he was head of KPMG’s Global Deal Advisory Business for Insurance. He has lived in Sydney, Hong Kong, Zurich and London, working with the world’s largest insurers and reinsurers.

The pendulum appears to be swinging back toward complacency for all too many companies, especially SMBs, after the WannaCry attack.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Byron Acohido is a business journalist who has been writing about cybersecurity and privacy since 2004, and currently blogs at LastWatchdog.com.

PwC’s survey found that executive confidence in their digital IQ had dropped a stunning 15 percentage points from the year before.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Chris Curran is a principal and chief technologist for PwC's advisory practice in the U.S. Curran advises senior executives on their most complex and strategic technology issues and has global experience in designing and implementing high-value technology initiatives across industries.

Is machine learning really bias-free? And how can we leverage this tool much more consciously than we do now?

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Oren Steinberg is an experienced CEO and entrepreneur with a demonstrated history of working in the big-data, digital-health and insurtech industries.

It seems so obvious: The hand of the taker is responsible for the deliberate action of suicide. But that perspective is too limited.

B.o.B tweeted, “The cities in the background are approx. 16miles apart....where is the curve? please explain this. "

Look, it’s obvious the Earth is flat.

Going back a thousand years, the Earth would in fact have looked downright flat to every one of us. From the every-man perspective, with a limited view, this appeared to be obvious for thousands of years.

Of course, there have always been signs that our limited view as humans was, well, limited. The first clue is that in every lunar eclipse we see the shadow of the earth cast against the moon. And we see a circle.

B.o.B tweeted, “The cities in the background are approx. 16miles apart....where is the curve? please explain this. "

Look, it’s obvious the Earth is flat.

Going back a thousand years, the Earth would in fact have looked downright flat to every one of us. From the every-man perspective, with a limited view, this appeared to be obvious for thousands of years.

Of course, there have always been signs that our limited view as humans was, well, limited. The first clue is that in every lunar eclipse we see the shadow of the earth cast against the moon. And we see a circle.

Tyson also explained to B.o.B that the Foucault pendulum demonstrates that the earth rotates. These clues could have been put together (and were) long before satellites or space travel. The conclusion: The world must be a ball!

Apparently, this was way too much looking through a glass darkly and didn’t persuade B.o.B. He believes the pictures of the round earth are the CGI creations of a conspiracy, and, in reality, most humans have not seen this view with their own eyes.

However, we could try to change his perspective. Instead of 16 miles across, let’s go one more mile. Let’s make it 17 miles — but straight up. Now, the curvature of the great, great big planet begins to emerge. The “Aha!” moment.

See also: Blueprint for Suicide Prevention

In life, we don’t always get the 17-mile perspective. Sometimes we fall one mile short. What seems obvious could not be more wrong, and sometimes, unlike with B.o.B's tweets, there are consequences.

I wish we could zip up 17 miles to see the true perspective on suicide, but it’s going to take some faith. Let’s look at the clues and what doesn’t fit, like that nagging circle shadow of the Earth on the moon.

Tyson also explained to B.o.B that the Foucault pendulum demonstrates that the earth rotates. These clues could have been put together (and were) long before satellites or space travel. The conclusion: The world must be a ball!

Apparently, this was way too much looking through a glass darkly and didn’t persuade B.o.B. He believes the pictures of the round earth are the CGI creations of a conspiracy, and, in reality, most humans have not seen this view with their own eyes.

However, we could try to change his perspective. Instead of 16 miles across, let’s go one more mile. Let’s make it 17 miles — but straight up. Now, the curvature of the great, great big planet begins to emerge. The “Aha!” moment.

See also: Blueprint for Suicide Prevention

In life, we don’t always get the 17-mile perspective. Sometimes we fall one mile short. What seems obvious could not be more wrong, and sometimes, unlike with B.o.B's tweets, there are consequences.

I wish we could zip up 17 miles to see the true perspective on suicide, but it’s going to take some faith. Let’s look at the clues and what doesn’t fit, like that nagging circle shadow of the Earth on the moon.

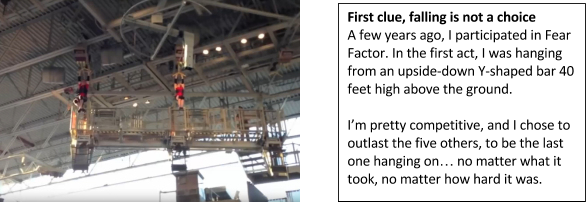

The approach I describe in the caption sounded really good… until the moment the platform underneath me dropped away. I was immediately slipping on the bar, struggling to hold on, my hands sweaty. I doubled down on my grip, but, quickly, my muscles began to ache, and my forearms ballooned like Popeye's. The pain intensified as the seconds passed.

I relaxed my breathing and went to my happy place (a beach in my mind with gentle waves lapping). That strategy was good for a couple seconds, but it still didn't work.

Finally, I was simply repeating to myself, “Hold on one more second, one more second.”

It was a long way to fall, so I desperately wanted to hang on. But I could not. Gravity and fatigue forced me to succumb to the pain.

You can watch my embarrassing fall. (YouTube Video).

Pain is not a choice

Many of us somehow think we've experienced enough pain through the normal ups and downs of being human that we have at least some insight into what leads people to suicide. One of America’s top novelists, William Styron, said, Not a chance. His book, “A Darkness Visible,” about his own debilitating and suicidal depression, is titled after John Milton’s description of Hell in “Paradise Lost.”

No light; but rather darkness visible

Where peace and rest can never dwell, hope never comes

That comes to all, but torture without end

One of our most talented writers ever, Styron said his depression was so mysteriously painful and elusive as to verge on being beyond description. He wrote, “It thus remains nearly incomprehensible to those who haven’t experienced extreme mode.”

If you haven’t experienced this kind of darkness, anguish, the clinical phrase “psychic distress” probably doesn’t help much. Styron offers the metaphor of physical pain to help us grasp what it’s like. But, frankly, many with lived experience say they would definitely prefer physical pain to this anguish.

Putting the Clues Together

So, some of you are thinking, I get what you are saying, but my loved one didn’t fall passively. I’m sure they were in pain, but they took a deliberate action. They pulled a trigger. They ingested a poison.

So, let’s put these two clues together but reverse the order. The pain. And the response.

After my first marathon, when my legs had cramped badly, I decided to try an ice bath and jumped right in. I bolted. I was propelled. Exiting the tub filled every neural pathway of my mind, and my hands and body flailed as if completely disconnected from my conscious decision-making process.

My example references an acute pain, but extend that into a chronic day-over-day anguish that blinds the person to the possibility of a better day. Perhaps people do not choose suicide so much as they finally succumb because they just don’t have the supports, resources, hope, etc. to hold on any longer. Their strength is extinguished and utterly fails.

See also: Employers’ Role in Preventing Suicide

Is Suicide a Choice?

The every-man perspective is that suicide is a choice. Robin Williams committed suicide. And it’s the hand of the taker that is completely responsible for the choice and deliberate action.

It seems so obvious. But it’s the limited, 16-mile perspective, the one we all have, and it's one mile short of the truth.

Someday, we’ll have the space-station view — and with it the solutions to create Zero Suicide.

But, for now, it’s time we study the signs, trust the clues and be brave to stand behind them.

Here’s a different headline:

“Robin Williams lost his battle. Tragically, he succumbed and died of suicide.”

Loving, respectful, true.

When you can’t hang on any longer, you can’t hang on. As I watch the video of my fall on Fear Factor, it looks like my right hand is still holding on to an invisible bar. I never, ever stopped choosing to hang on. But I fell.

Believe the signs. Change your perspective. Use your voice. Let’s change that great big beautiful round planet we live on, and let’s do it together by doubling down on our efforts to help others hold on.

The approach I describe in the caption sounded really good… until the moment the platform underneath me dropped away. I was immediately slipping on the bar, struggling to hold on, my hands sweaty. I doubled down on my grip, but, quickly, my muscles began to ache, and my forearms ballooned like Popeye's. The pain intensified as the seconds passed.

I relaxed my breathing and went to my happy place (a beach in my mind with gentle waves lapping). That strategy was good for a couple seconds, but it still didn't work.

Finally, I was simply repeating to myself, “Hold on one more second, one more second.”

It was a long way to fall, so I desperately wanted to hang on. But I could not. Gravity and fatigue forced me to succumb to the pain.

You can watch my embarrassing fall. (YouTube Video).

Pain is not a choice

Many of us somehow think we've experienced enough pain through the normal ups and downs of being human that we have at least some insight into what leads people to suicide. One of America’s top novelists, William Styron, said, Not a chance. His book, “A Darkness Visible,” about his own debilitating and suicidal depression, is titled after John Milton’s description of Hell in “Paradise Lost.”

No light; but rather darkness visible

Where peace and rest can never dwell, hope never comes

That comes to all, but torture without end

One of our most talented writers ever, Styron said his depression was so mysteriously painful and elusive as to verge on being beyond description. He wrote, “It thus remains nearly incomprehensible to those who haven’t experienced extreme mode.”

If you haven’t experienced this kind of darkness, anguish, the clinical phrase “psychic distress” probably doesn’t help much. Styron offers the metaphor of physical pain to help us grasp what it’s like. But, frankly, many with lived experience say they would definitely prefer physical pain to this anguish.

Putting the Clues Together

So, some of you are thinking, I get what you are saying, but my loved one didn’t fall passively. I’m sure they were in pain, but they took a deliberate action. They pulled a trigger. They ingested a poison.

So, let’s put these two clues together but reverse the order. The pain. And the response.

After my first marathon, when my legs had cramped badly, I decided to try an ice bath and jumped right in. I bolted. I was propelled. Exiting the tub filled every neural pathway of my mind, and my hands and body flailed as if completely disconnected from my conscious decision-making process.

My example references an acute pain, but extend that into a chronic day-over-day anguish that blinds the person to the possibility of a better day. Perhaps people do not choose suicide so much as they finally succumb because they just don’t have the supports, resources, hope, etc. to hold on any longer. Their strength is extinguished and utterly fails.

See also: Employers’ Role in Preventing Suicide

Is Suicide a Choice?

The every-man perspective is that suicide is a choice. Robin Williams committed suicide. And it’s the hand of the taker that is completely responsible for the choice and deliberate action.

It seems so obvious. But it’s the limited, 16-mile perspective, the one we all have, and it's one mile short of the truth.

Someday, we’ll have the space-station view — and with it the solutions to create Zero Suicide.

But, for now, it’s time we study the signs, trust the clues and be brave to stand behind them.

Here’s a different headline:

“Robin Williams lost his battle. Tragically, he succumbed and died of suicide.”

Loving, respectful, true.

When you can’t hang on any longer, you can’t hang on. As I watch the video of my fall on Fear Factor, it looks like my right hand is still holding on to an invisible bar. I never, ever stopped choosing to hang on. But I fell.

Believe the signs. Change your perspective. Use your voice. Let’s change that great big beautiful round planet we live on, and let’s do it together by doubling down on our efforts to help others hold on.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

David Covington, LPC, MBA is CEO and president of RI International, a partner in Behavioral Health Link, co-founder of CrisisTech 360, and leads the international initiatives “Crisis Now” and “Zero Suicide.”

As you contemplate the introduction of artificial intelligence, you should articulate what mix of three approaches works best for you.

Though it is the closest machine to a human brain, a deep learning neural network is not suitable for all problems. It requires multiple processors with enormous computing power, far beyond conventional IT architecture; it will learn only by processing enormous amounts of data; and its decision processes are not transparent.

News aggregation software, for example, had long relied on rudimentary AI to curate articles based on people’s requests. Then it evolved to analyze behavior, tracking the way people clicked on articles and the time they spent reading, and adjusting the selections accordingly. Next it aggregated individual users’ behavior with the larger population, particularly those who had similar media habits. Now it is incorporating broader data about the way readers’ interests change over time, to anticipate what people are likely to want to see next, even if they have never clicked on that topic before. Tomorrow’s AI aggregators will be able to detect and counter “fake news” by scanning for inconsistencies and routing people to alternative perspectives.

AI applications in daily use include all smartphone digital assistants, email programs that sort entries by importance, voice recognition systems, image recognition apps such as Facebook Picture Search, digital assistants such as Amazon Echo and Google Home and much of the emerging Industrial Internet. Some AI apps are targeted at minor frustrations — DoNotPay, an online legal bot, has reversed thousands of parking tickets — and others, such as connected car and language translation technologies, represent fundamental shifts in the way people live. A growing number are aimed at improving human behavior; for instance, GM’s 2016 Chevrolet Malibu feeds data from sensors into a backseat driver–like guidance system for teenagers at the wheel.

Despite all this activity, the market for AI is still small. Market research firm Tractica estimated 2016 revenues at just $644 million. But it expects hockey stick-style growth, reaching $15 billion by 2022 and accelerating thereafter. In late 2016, there were about 1,500 AI-related startups in the U.S. alone, and total funding in 2016 reached a record $5 billion. Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Salesforce.com and other tech companies are snapping up AI software companies, and large, established companies are recruiting deep learning talent and, like Monsanto, buying AI companies specializing in their markets. To make the most of this technology in your enterprise, consider the three main ways that businesses can or will use AI:

Though it is the closest machine to a human brain, a deep learning neural network is not suitable for all problems. It requires multiple processors with enormous computing power, far beyond conventional IT architecture; it will learn only by processing enormous amounts of data; and its decision processes are not transparent.

News aggregation software, for example, had long relied on rudimentary AI to curate articles based on people’s requests. Then it evolved to analyze behavior, tracking the way people clicked on articles and the time they spent reading, and adjusting the selections accordingly. Next it aggregated individual users’ behavior with the larger population, particularly those who had similar media habits. Now it is incorporating broader data about the way readers’ interests change over time, to anticipate what people are likely to want to see next, even if they have never clicked on that topic before. Tomorrow’s AI aggregators will be able to detect and counter “fake news” by scanning for inconsistencies and routing people to alternative perspectives.

AI applications in daily use include all smartphone digital assistants, email programs that sort entries by importance, voice recognition systems, image recognition apps such as Facebook Picture Search, digital assistants such as Amazon Echo and Google Home and much of the emerging Industrial Internet. Some AI apps are targeted at minor frustrations — DoNotPay, an online legal bot, has reversed thousands of parking tickets — and others, such as connected car and language translation technologies, represent fundamental shifts in the way people live. A growing number are aimed at improving human behavior; for instance, GM’s 2016 Chevrolet Malibu feeds data from sensors into a backseat driver–like guidance system for teenagers at the wheel.

Despite all this activity, the market for AI is still small. Market research firm Tractica estimated 2016 revenues at just $644 million. But it expects hockey stick-style growth, reaching $15 billion by 2022 and accelerating thereafter. In late 2016, there were about 1,500 AI-related startups in the U.S. alone, and total funding in 2016 reached a record $5 billion. Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Salesforce.com and other tech companies are snapping up AI software companies, and large, established companies are recruiting deep learning talent and, like Monsanto, buying AI companies specializing in their markets. To make the most of this technology in your enterprise, consider the three main ways that businesses can or will use AI:

Assisted Intelligence

Assisted intelligence amplifies the value of existing activity. For example, Google’s Gmail sorts incoming email into “Primary,” “Social" and “Promotion” default tabs. The algorithm, trained with data from millions of other users’ emails, makes people more efficient without changing the way they use email or altering the value it provides.

Assisted intelligence tends to involve clearly defined, rules-based, repeatable tasks. These include automated assembly lines and other uses of physical robots; robotic process automation, in which software-based agents simulate the online activities of a human being; and back-office functions such as billing, finance and regulatory compliance. This form of AI can be used to verify and cross-check data — for example, when paper checks are read and verified by a bank’s ATM. Assisted intelligence has already become common in some enterprise software processes. In “opportunity to order” (basic sales) and “order to cash” (receiving and processing customer orders), the software offers guidance and direction that was formerly available only from people.

The Oscar W. Larson Co. used assisted intelligence to improve its field service operations. This is a 70-plus-year-old family-owned general contractor, which, among other services to the oil and gas industry, provides maintenance and repair for point-of-sales systems and fuel dispensers at gas stations. One costly and irritating problem is “truck rerolls”: service calls that have to be rescheduled because the technician lacks the tools, parts or expertise for a particular issue. After analyzing data on service calls, the AI software showed how to reduce truck rerolls by 20%, a rate that should continue to improve as the software learns to recognize more patterns.

Assisted intelligence apps often involve computer models of complex realities that allow businesses to test decisions with less risk. For example, one auto manufacturer has developed a simulation of consumer behavior, incorporating data about the types of trips people make, the ways those affect supply and demand for motor vehicles and the variations in those patterns for different city topologies, marketing approaches and vehicle price ranges. The model spells out more than 200,000 variations for the automaker to consider and simulates the potential success of any tested variation, thus assisting in the design of car launches. As the automaker introduces cars and the simulator incorporates the data on outcomes from each launch, the model’s predictions will become ever more accurate.

AI-based packages of this sort are available on more and more enterprise software platforms. Success with assisted intelligence should lead to improvements in conventional business metrics such as labor productivity, revenues or margins per employee and average time to completion for processes. Much of the cost involved is in the staff you hire, who must be skilled at marshaling and interpreting data. To evaluate where to deploy assisted intelligence, consider two questions: What products or services could you easily make more marketable if they were more automatically responsive to your customers? Which of your current processes and practices, including your decision-making practices, would be more powerful with more intelligence?

Augmented Intelligence

Augmented intelligence software lends new capability to human activity, permitting enterprises to do things they couldn’t do before. Unlike assisted intelligence, it fundamentally alters the nature of the task, and business models change accordingly.

For example, Netflix uses machine learning algorithms to do something media has never done before: suggest choices customers would probably not have found themselves, based not just on the customer’s patterns of behavior but on those of the audience at large. A Netflix user, unlike a cable TV pay-per-view customer, can easily switch from one premium video to another without penalty, after just a few minutes. This gives consumers more control over their time. They use it to choose videos more tailored to the way they feel at any given moment. Every time that happens, the system records that observation and adjusts its recommendation list — and it enables Netflix to tailor its next round of videos to user preferences more accurately. This leads to reduced costs and higher profits per movie, and a more enthusiastic audience, which then enables more investments in personalization (and AI). Left outside this virtuous circle are conventional advertising and television networks. No wonder other video channels, such as HBO and Amazon, as well as recorded music channels such as Spotify, have moved to similar models.

Over time, as algorithms grow more sophisticated, the symbiotic relationship between human and AI will further change entertainment industry practices. The unit of viewing decision will probably become the scene, not the story; algorithms will link scenes to audience emotions. A consumer might ask to see only scenes where a Meryl Streep character is falling in love, or to trace a particular type of swordplay from one action movie to another. Data accumulating from these choices will further refine the ability of the entertainment industry to spark people’s emotions, satisfy their curiosity and gain their loyalty.

Another current use of augmented intelligence is in legal research. Though most cases are searchable online, finding relevant precedents still requires many hours of sifting through past opinions. Luminance, a startup specializing in legal research, can run through thousands of cases in a very short time, providing inferences about their relevance to a current proceeding. Systems like these don’t yet replace human legal research. But they dramatically reduce the rote work conducted by associate attorneys, a job rated as the least satisfying in the U.S. Similar applications are emerging for other types of data sifting, including financial audits, interpreting regulations, finding patterns in epidemiological data and (as noted above) farming.

To develop applications like these, you’ll need to marshal your own imagination to look for products, services or processes that would not be possible at all without AI. For example, an AI system can track a wide number of product features, warranty costs, repeat purchase rates and more general purchasing metrics, bringing only unusual or noteworthy correlations to your attention. Are a high number of repairs associated with a particular region, material or line of products? Could you use this information to redesign your products, avoid recalls or spark innovation in some way?

The success of an augmented intelligence effort depends on whether it has enabled your company to do new things. To assess this capability, track your margins, innovation cycles, customer experience and revenue growth as potential proxies. Also watch your impact on disruption: Are your new innovations doing to some part of the business ecosystem what, say, ride-hailing services are doing to conventional taxi companies?

You won’t find many off-the-shelf applications for augmented intelligence. They involve advanced forms of machine learning and natural language processing, plus specialized interfaces tailored to your company and industry. However, you can build bespoke augmented intelligence applications on cloud-based enterprise platforms, most of which allow modifications in open source code. Given the unstructured nature of your most critical decision processes, an augmented intelligence application would require voluminous historical data from your own company, along with data from the rest of your industry and related fields (such as demographics). This will help the system distinguish external factors, such as competition and economic conditions, from the impact of your own decisions.

The greatest change from augmented intelligence may be felt by senior decision makers, as the new models often give them new alternatives to consider that don’t match their past experience or gut feelings. They should be open to those alternatives, but also skeptical. AI systems are not infallible; just like any human guide, they must show consistency, explain their decisions and counter biases, or they will lose their value.

Autonomous Intelligence

Very few autonomous intelligence systems — systems that make decisions without direct human involvement or oversight — are in widespread use today. Early examples include automated trading in the stock market (about 75% of Nasdaq trading is conducted autonomously) and facial recognition. In some circumstances, algorithms are better than people at identifying other people. Other early examples include robots that dispose of bombs, gather deep-sea data, maintain space stations and perform other tasks inherently unsafe for people.

The most eagerly anticipated forms of autonomous intelligence — self-driving cars and full-fledged language translation programs — are not yet ready for general use. The closest autonomous service so far is Tencent’s messaging and social media platform WeChat, which has close to 800 million daily active users, most of them in China. The program, which was designed primarily for use on smartphones, offers relatively sophisticated voice recognition, Chinese-to-English language translation, facial recognition (including suggestions of celebrities who look like the person holding the phone) and virtual bot friends that can play guessing games. Notwithstanding their cleverness and their pioneering use of natural language processing, these are still niche applications, and still very limited by technology. Some of the most popular AI apps, for example, are small, menu- and rule-driven programs, which conduct fairly rudimentary conversations around a limited group of options.

See also: Machine Learning to the Rescue on Cyber?

Despite the lead time required to bring the technology further along, any business prepared to base a strategy on advanced digital technology should be thinking seriously about autonomous intelligence now. The Internet of Things will generate vast amounts of information, more than humans can reasonably interpret. In commercial aircraft, for example, so much flight data is gathered that engineers can’t process it all; thus, Boeing has announced a $7.5 million partnership with Carnegie Mellon University, along with other efforts to develop AI systems that can, for example, predict when airplanes will need maintenance. Autonomous intelligence’s greatest challenge may not be technological at all — it may be companies’ ability to build in enough transparency for people to trust these systems to act in their best interest.

First Steps

As you contemplate the introduction of artificial intelligence, articulate what mix of the three approaches works best for you.

Assisted Intelligence

Assisted intelligence amplifies the value of existing activity. For example, Google’s Gmail sorts incoming email into “Primary,” “Social" and “Promotion” default tabs. The algorithm, trained with data from millions of other users’ emails, makes people more efficient without changing the way they use email or altering the value it provides.

Assisted intelligence tends to involve clearly defined, rules-based, repeatable tasks. These include automated assembly lines and other uses of physical robots; robotic process automation, in which software-based agents simulate the online activities of a human being; and back-office functions such as billing, finance and regulatory compliance. This form of AI can be used to verify and cross-check data — for example, when paper checks are read and verified by a bank’s ATM. Assisted intelligence has already become common in some enterprise software processes. In “opportunity to order” (basic sales) and “order to cash” (receiving and processing customer orders), the software offers guidance and direction that was formerly available only from people.

The Oscar W. Larson Co. used assisted intelligence to improve its field service operations. This is a 70-plus-year-old family-owned general contractor, which, among other services to the oil and gas industry, provides maintenance and repair for point-of-sales systems and fuel dispensers at gas stations. One costly and irritating problem is “truck rerolls”: service calls that have to be rescheduled because the technician lacks the tools, parts or expertise for a particular issue. After analyzing data on service calls, the AI software showed how to reduce truck rerolls by 20%, a rate that should continue to improve as the software learns to recognize more patterns.

Assisted intelligence apps often involve computer models of complex realities that allow businesses to test decisions with less risk. For example, one auto manufacturer has developed a simulation of consumer behavior, incorporating data about the types of trips people make, the ways those affect supply and demand for motor vehicles and the variations in those patterns for different city topologies, marketing approaches and vehicle price ranges. The model spells out more than 200,000 variations for the automaker to consider and simulates the potential success of any tested variation, thus assisting in the design of car launches. As the automaker introduces cars and the simulator incorporates the data on outcomes from each launch, the model’s predictions will become ever more accurate.

AI-based packages of this sort are available on more and more enterprise software platforms. Success with assisted intelligence should lead to improvements in conventional business metrics such as labor productivity, revenues or margins per employee and average time to completion for processes. Much of the cost involved is in the staff you hire, who must be skilled at marshaling and interpreting data. To evaluate where to deploy assisted intelligence, consider two questions: What products or services could you easily make more marketable if they were more automatically responsive to your customers? Which of your current processes and practices, including your decision-making practices, would be more powerful with more intelligence?

Augmented Intelligence

Augmented intelligence software lends new capability to human activity, permitting enterprises to do things they couldn’t do before. Unlike assisted intelligence, it fundamentally alters the nature of the task, and business models change accordingly.

For example, Netflix uses machine learning algorithms to do something media has never done before: suggest choices customers would probably not have found themselves, based not just on the customer’s patterns of behavior but on those of the audience at large. A Netflix user, unlike a cable TV pay-per-view customer, can easily switch from one premium video to another without penalty, after just a few minutes. This gives consumers more control over their time. They use it to choose videos more tailored to the way they feel at any given moment. Every time that happens, the system records that observation and adjusts its recommendation list — and it enables Netflix to tailor its next round of videos to user preferences more accurately. This leads to reduced costs and higher profits per movie, and a more enthusiastic audience, which then enables more investments in personalization (and AI). Left outside this virtuous circle are conventional advertising and television networks. No wonder other video channels, such as HBO and Amazon, as well as recorded music channels such as Spotify, have moved to similar models.

Over time, as algorithms grow more sophisticated, the symbiotic relationship between human and AI will further change entertainment industry practices. The unit of viewing decision will probably become the scene, not the story; algorithms will link scenes to audience emotions. A consumer might ask to see only scenes where a Meryl Streep character is falling in love, or to trace a particular type of swordplay from one action movie to another. Data accumulating from these choices will further refine the ability of the entertainment industry to spark people’s emotions, satisfy their curiosity and gain their loyalty.

Another current use of augmented intelligence is in legal research. Though most cases are searchable online, finding relevant precedents still requires many hours of sifting through past opinions. Luminance, a startup specializing in legal research, can run through thousands of cases in a very short time, providing inferences about their relevance to a current proceeding. Systems like these don’t yet replace human legal research. But they dramatically reduce the rote work conducted by associate attorneys, a job rated as the least satisfying in the U.S. Similar applications are emerging for other types of data sifting, including financial audits, interpreting regulations, finding patterns in epidemiological data and (as noted above) farming.

To develop applications like these, you’ll need to marshal your own imagination to look for products, services or processes that would not be possible at all without AI. For example, an AI system can track a wide number of product features, warranty costs, repeat purchase rates and more general purchasing metrics, bringing only unusual or noteworthy correlations to your attention. Are a high number of repairs associated with a particular region, material or line of products? Could you use this information to redesign your products, avoid recalls or spark innovation in some way?

The success of an augmented intelligence effort depends on whether it has enabled your company to do new things. To assess this capability, track your margins, innovation cycles, customer experience and revenue growth as potential proxies. Also watch your impact on disruption: Are your new innovations doing to some part of the business ecosystem what, say, ride-hailing services are doing to conventional taxi companies?

You won’t find many off-the-shelf applications for augmented intelligence. They involve advanced forms of machine learning and natural language processing, plus specialized interfaces tailored to your company and industry. However, you can build bespoke augmented intelligence applications on cloud-based enterprise platforms, most of which allow modifications in open source code. Given the unstructured nature of your most critical decision processes, an augmented intelligence application would require voluminous historical data from your own company, along with data from the rest of your industry and related fields (such as demographics). This will help the system distinguish external factors, such as competition and economic conditions, from the impact of your own decisions.

The greatest change from augmented intelligence may be felt by senior decision makers, as the new models often give them new alternatives to consider that don’t match their past experience or gut feelings. They should be open to those alternatives, but also skeptical. AI systems are not infallible; just like any human guide, they must show consistency, explain their decisions and counter biases, or they will lose their value.

Autonomous Intelligence

Very few autonomous intelligence systems — systems that make decisions without direct human involvement or oversight — are in widespread use today. Early examples include automated trading in the stock market (about 75% of Nasdaq trading is conducted autonomously) and facial recognition. In some circumstances, algorithms are better than people at identifying other people. Other early examples include robots that dispose of bombs, gather deep-sea data, maintain space stations and perform other tasks inherently unsafe for people.

The most eagerly anticipated forms of autonomous intelligence — self-driving cars and full-fledged language translation programs — are not yet ready for general use. The closest autonomous service so far is Tencent’s messaging and social media platform WeChat, which has close to 800 million daily active users, most of them in China. The program, which was designed primarily for use on smartphones, offers relatively sophisticated voice recognition, Chinese-to-English language translation, facial recognition (including suggestions of celebrities who look like the person holding the phone) and virtual bot friends that can play guessing games. Notwithstanding their cleverness and their pioneering use of natural language processing, these are still niche applications, and still very limited by technology. Some of the most popular AI apps, for example, are small, menu- and rule-driven programs, which conduct fairly rudimentary conversations around a limited group of options.

See also: Machine Learning to the Rescue on Cyber?

Despite the lead time required to bring the technology further along, any business prepared to base a strategy on advanced digital technology should be thinking seriously about autonomous intelligence now. The Internet of Things will generate vast amounts of information, more than humans can reasonably interpret. In commercial aircraft, for example, so much flight data is gathered that engineers can’t process it all; thus, Boeing has announced a $7.5 million partnership with Carnegie Mellon University, along with other efforts to develop AI systems that can, for example, predict when airplanes will need maintenance. Autonomous intelligence’s greatest challenge may not be technological at all — it may be companies’ ability to build in enough transparency for people to trust these systems to act in their best interest.

First Steps

As you contemplate the introduction of artificial intelligence, articulate what mix of the three approaches works best for you.

Though investments in AI may seem expensive now, the costs will decline over the next 10 years as the software becomes more commoditized. “As this technology continues to mature,” writes Daniel Eckert, a managing director in emerging technology services for PwC US, “we should see the price adhere toward a utility model and flatten out. We expect a tiered pricing model to be introduced: a free (or freemium model) for simple activities, and a premium model for discrete, business-differentiating services.”

AI is often sold on the premise that it will replace human labor at lower cost — and the effect on employment could be devastating, though no one knows for sure. Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne of Oxford University’s engineering school have calculated that AI will put 47% of the jobs in the U.S. at risk; a 2016 Forrester research report estimated it at 6%, at least by 2025. On the other hand, Baidu Research head (and deep learning pioneer) Andrew Ng recently said, “AI is the new electricity,” meaning that it will be found everywhere and create jobs that weren’t imaginable before its appearance.

At the same time that AI threatens the loss of an almost unimaginable number of jobs, it is also a hungry, unsatisfied employer. The lack of capable talent — people skilled in deep learning technology and analytics — may well turn out to be the biggest obstacle for large companies. The greatest opportunities may thus be for independent businesspeople, including farmers like Jeff Heepke, who no longer need scale to compete with large companies, because AI has leveled the playing field.

It is still too early to say which types of companies will be the most successful in this area — and we don’t yet have an AI model to predict it for us. In the end, we cannot even say for sure that the companies that enter the field first will be the most successful. The dominant players will be those that, like Climate Corp., Oscar W. Larson, Netflix and many other companies large and small, have taken AI to heart as a way to become far more capable, in a far more relevant way, than they otherwise would ever be.

Though investments in AI may seem expensive now, the costs will decline over the next 10 years as the software becomes more commoditized. “As this technology continues to mature,” writes Daniel Eckert, a managing director in emerging technology services for PwC US, “we should see the price adhere toward a utility model and flatten out. We expect a tiered pricing model to be introduced: a free (or freemium model) for simple activities, and a premium model for discrete, business-differentiating services.”

AI is often sold on the premise that it will replace human labor at lower cost — and the effect on employment could be devastating, though no one knows for sure. Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne of Oxford University’s engineering school have calculated that AI will put 47% of the jobs in the U.S. at risk; a 2016 Forrester research report estimated it at 6%, at least by 2025. On the other hand, Baidu Research head (and deep learning pioneer) Andrew Ng recently said, “AI is the new electricity,” meaning that it will be found everywhere and create jobs that weren’t imaginable before its appearance.

At the same time that AI threatens the loss of an almost unimaginable number of jobs, it is also a hungry, unsatisfied employer. The lack of capable talent — people skilled in deep learning technology and analytics — may well turn out to be the biggest obstacle for large companies. The greatest opportunities may thus be for independent businesspeople, including farmers like Jeff Heepke, who no longer need scale to compete with large companies, because AI has leveled the playing field.

It is still too early to say which types of companies will be the most successful in this area — and we don’t yet have an AI model to predict it for us. In the end, we cannot even say for sure that the companies that enter the field first will be the most successful. The dominant players will be those that, like Climate Corp., Oscar W. Larson, Netflix and many other companies large and small, have taken AI to heart as a way to become far more capable, in a far more relevant way, than they otherwise would ever be.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Anand Rao is a principal in PwC’s advisory practice. He leads the insurance analytics practice, is the innovation lead for the U.S. firm’s analytics group and is the co-lead for the Global Project Blue, Future of Insurance research. Before joining PwC, Rao was with Mitchell Madison Group in London.