How to Shield Your Sensitive Data

It’s imperative to ensure that no matter where your content travels or what device you use, at any point it is protected from getting into the wrong hands.

It’s imperative to ensure that no matter where your content travels or what device you use, at any point it is protected from getting into the wrong hands.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Byron Acohido is a business journalist who has been writing about cybersecurity and privacy since 2004, and currently blogs at LastWatchdog.com.

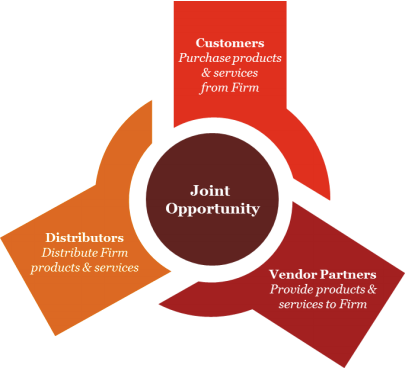

Though our organizations are independent, we are all a part of an interdependent ecosystem for service delivery — a highly relevant concept.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Denise Garth is senior vice president, strategic marketing, responsible for leading marketing, industry relations and innovation in support of Majesco's client-centric strategy.

Historically, managing and paying producers has been an afterthought. But the topic now has to be addressed.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Brad Denning is a partner with PwC’s Financial Services Advisory practice, combining more than 20 years of industry and consulting experience. Denning is PwC’s partner sponsor for our producer management and compensation practice.

Atanu Ghosh works at Microsoft as an industry digital strategy.

With "repeal and replace" looking less and less likely for Obamacare, here is a long list of ways it can be repaired and improved.

Average cost for an average annual worker and employer contributions for single and family (Kaiser Family Foundation): Single coverage, all firms: total $6,445 (employer share, $5,306; employee share, $1,129). Family Coverage: total $18,142 (employer share: $12,865, employee share: $5,277). In 2017, the maximum allowable cost-sharing (including out-of-pocket costs for deductibles, co-payments and co-insurance) is $7,150 for self-only coverage and $14,300 for families.

Most marketplace consumers have affordable options. More than 7 in 10 (72%) of current enrollees can find a plan for $75 or less in premiums per month, after applicable tax credits in 2017. Nearly 8 in 10 (77%) can find a plan for $100 or less in premiums per month, after applicable tax credits in 2017.

Two recent Kaiser Health Tracking Polls looked at Americans' current experience with and worries about healthcare costs, including their ability to afford premiums and deductibles. For the most part, the majority of the public does not have difficulty paying for care, but significant minorities do, and even more worry about their ability to afford care in the future. Four in ten (43%) adults with health insurance say they have difficulty affording their deductible, and roughly a third say they have trouble affording their premiums and other cost sharing; all shares have increased since 2015. Among people with health insurance, one in five (20%) working-age Americans report having problems paying medical bills in the past year that often cause serious financial challenges and changes in employment and lifestyle.

Even for those who may not have had difficulty affording care or paying medical bills, there is still a widespread worry about being able to afford needed healthcare services, with half of the public expressing worry about this. Healthcare-related worries and problems paying for care are particularly prevalent among the uninsured, individuals with lower incomes and those in poorer health. Women and members of racial minority groups are also more likely than their peers to report these issues.

Making health insurance affordable again

Medicare Part A is currently available with no premium if you or your spouses paid Medicare taxes. Medicare Part A can continue to be offered for free to those who pay taxes and for those who qualify for Medicaid.

Medicare Part B premiums are subsidized with the government paying a substantial portion (about 75%) of the Part B premium, and the beneficiary paying the remaining 25%. Premiums are subsidized, with the gross total monthly premium being $134. This amount is reduced to $109 on average for those on Social Security. Depending on your income, the premium can increase to $428.60 monthly. View information on Part B premiums here.

Medicare prescription drug coverage helps pay for your prescription drugs. For most beneficiaries, the government pays a major portion of the total costs for this coverage, and the beneficiary pays the rest. Prescription drug plan costs vary depending on the plan, as does whether you get extra help with your portion of the Medicare prescription drug coverage costs. Higher earners pay more.

Beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage typically pay monthly premiums for additional benefits covered by their plan, in addition to the Part B premium. Kaiser Family Foundation figures.

How is Medicare financed?

Medicare Part A is financed primarily through a 2.9% tax on earnings paid by employers and employees (1.45% each) (accounting for 88% of Part A revenue). Higher-income taxpayers (more than $200,000/individual and $250,000/couple) pay a higher payroll tax on earnings (2.35%). To pay for Part A, taxes will need to go up, but the trade-off is that premiums for the supplemental coverage will be less because it covers less - net impact to the consumer is zero.

Medicare Part B is financed through general revenues (73%), beneficiary premiums (25%), and interest and other sources (2%). Beneficiaries with annual incomes over $85,000/individual or $170,000/couple pay a higher, income-related Part B premium, ranging from 35% to 80%. The ACA froze the income thresholds through 2019, and, beginning in 2020, the income thresholds will once again be indexed to inflation, based on their levels in 2019 (a provision in the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015). As a result, the number and share of beneficiaries paying income-related premiums will increase as the number of people on Medicare continues to grow in future years and as their incomes rise. Premiums would be less than under current individual insurance plans because certain essential benefits would be covered by the expanded Medicare Part A.

Medicare Part D is financed by general revenues (77%), beneficiary premiums (14%) and state payments for dually eligible beneficiaries (10%). As with Part B, higher-income enrollees pay a larger share of the cost of Part D coverage.

Medicare Part C (The Medicare Advantage program) is not separately financed. Medicare Advantage plans such as HMOs and PPOs cover all Part A, Part B and (typically) Part D benefits. Beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans typically pay monthly premiums for additional benefits covered by their plan in addition to the Part B premium.

From Kaiser Foundation: The Facts on Medicare Spending and financing worksheet.

The public need for increased plan choice and market stability

Health insurance exchanges haven’t worked so far. Currently, there are only 12 state-based marketplaces; five state-based marketplace-federal platforms, six state-partnership marketplaces; and 28 federally facilitated marketplaces. A list of State Health Insurance Marketplace types can be be found on the Kaiser Family Foundation website.

The Congressional Budget Office said that although the ACA’s markets are “stable in most areas,” about 42% of those buying coverage on Obamacare’s exchanges had just one or two insurers to pick from for this year. Currently, one in three counties has just one insurer in the local market, significantly less choice than the one in 14 counted last year, according to the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation. And five states have a single insurer: Alabama, Alaska, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Wyoming. Moving to a Medicare-based system would mean that, if an insurance company decides to leave a county or state, the residents still have access to health insurance. There are parts of Tennessee where there may not be any exchange insurance options for 2018. And Oklahoma’s insurance regulator warned last week that his state’s lone carrier may quit the market.

With issues facing the Affordable Care Act on subsidies, Medicaid expansion and other potential changes, consumers may end up with few choices as insurance companies decide to not participate in the exchanges in the future. Humana has announced that it will drop out of the 11 states where it offers ACA plans. Other major insurance companies, including Anthem, Aetna and Molina Healthcare, have warned that they can’t commit to participating in the ACA exchanges in 2018.

Medi-gap supplements and Medicare Advantage will boost choice. Medicare Advantage has proven to be popular, and enrollment is expected to increase to all-time high of 18.5 million Medicare beneficiaries. In 2017, this will represent about 32% of Medicare beneficiaries. Typical Medicare Advantage plan providers offer managed care plans.

Access to the Medicare Advantage program remains nearly universal, with 99% of Medicare beneficiaries having access to a health plan in their area. Access to supplemental benefits, such as dental and vision benefits, continues to grow. More than 94% of Medicare beneficiaries have access to a $0 premium Medicare Advantage plan. 100% of Medicare beneficiaries – including Medicare Advantage enrollees – have access to recommended Medicare-covered preventive services at zero cost sharing.

Consumers have access to information to improve plan choice. Medicare beneficiaries are allowed a one-time opportunity to switch to a five-star Medicare Advantage plan or prescription drug plan in their area any time during the year. Medicare has a low-performing icon on Medicare.gov so beneficiaries know which plans are not performing well. Medicare Advantage plan sponsors are also required spend at least 85% of premiums on quality and care delivery and not on overhead, profit or administrative costs.

According to a recent fact sheet from CMS.gov, Moving Medicare Advantage and Part D Forward: Some counties have low Medicare Advantage penetration rates because the number of hospitals and doctors is too low for use of a managed care network to make much sense. This mirrors some of the reasons why there are few marketplace options in certain counties and state and is exactly why there needs to be a plan available through the federal government, as with the current Medicare Parts B & D.

When retirees are unhappy with Medicare Advantage plan provider directories, they typically combine traditional Medicare coverage with Medicare supplement insurance, or Medigap coverage. Retirees using Medigap coverage with traditional Medicare can use any provider that takes Medicare.

Consumers are better able to control their Medicare Advantage Plan (Part C) premiums by choosing a plan without a monthly premium, having a plan that pays part of Medicare Part B, having a deductible, choosing a copayment (coinsurance) amount, choosing the type of health services, setting their limit on annual out-of-pocket expenses and choosing whether they go to a doctor or other medical service supplier who accepts assignment (from Medicare).

Balancing the risk pool

The risk pool must be sufficiently large to take advantage of the law of big numbers. Insurance companies reflect healthcare costs, and their mission is to spread the risk and be balanced. If the risk pool is unbalanced by covering too many sick people and not enough healthy people, the insurance company will have higher claims and will need to collect higher premiums. When this happens, healthier individuals are usually the first to drop coverage, which they feel is not needed, which leaves a growing proportion of “less healthy” individuals. At some point, the imbalance becomes unsustainable, and the carriers exit the market entirely.

The only reason healthy people buy health insurance is that they know that if they wait until they get really sick no insurance company will sell them a policy. The same principle holds true for all insurance products. You can’t buy auto insurance after you get into an accident. You can’t buy life insurance at a reasonable cost after your doctor has given you six months to live. The fact that your car is already wrecked, or your arteries already clogged, are pre-existing conditions that no insurance company would be expected to ignore.

Allowing voters the low-cost option to buy health insurance after they actually need it is very popular. It’s like promising motorists they can stop paying their monthly auto insurance premium and just buy a policy after they have an accident. If the government were to require this, all auto insurance companies would quickly go out of business (unless they were bailed out by the government).

Contrary to belief, younger people (millennials) do want want health insurance and consider it a top life priority, according to a study from research firm Benson Strategy Group. Eighty-six percent of millennials are insured, and 85% said it is "absolutely essential" or "very important" to have coverage, according to the survey. Researchers said most millennials get their insurance through an employer (39%) or Medicaid (20%).

Shifting work force and ending the current group health insurance market

The U.S. work force is shifting, with fewer Americans working at large employers and being covered by group health insurance. Americans are moving more to being “gig” employees, freelancers/consultants, part-time employees, job movement, cash employees and seasonal employees and continuing to start businesses.

For employers, counting employees for purposes of ACA compliance seems to be an expensive nightmare.

The size of your employer is a major factor on if health insurance is offered: 96% of firms with 100 or more employees offered health insurance, 89% of employers between 50 and 99 employees offer health insurance, while 53% of employees with three to 49 workers offered health insurance; the average is 56% of employers offering coverage. So unless you work at a big firm, you can't count on health insurance anyway. And dependent on the size of the firm, there is no guarantee that it will offer coverage to spouses, dependents or domestic partners.

Even those with group health insurance received less value than historically. According to a recent LinkedIn study (2/2017), a total of 63% of respondents indicated that their healthcare benefits were either more expensive or stingier than in the previous year, and 40% saw both an increase in premium costs as well as higher out-of-pocket copays and deductibles when they used their health plans.

In a survey (2/2017), nearly one in five LinkedIn members in the U.S. (or 19%) indicated that health insurance has been their primary reason for taking, leaving or keeping a job.

If health insurance is available as proposed through individual, portable insurance plans, there will no longer be employer health insurance programs. Excluding premiums from taxes was worth about $250 billion in forgone tax revenue in 2013, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Some health economists have argued that the exemption artificially drives up health spending. Employer-provided health benefits, often worth thousands of dollars a year, aren’t taxed as wages are. People who have to buy coverage on their own don’t enjoy the same tax advantage. Currently, employers do offer supplemental benefits to their employees that they often pay at least part of the premium.

See also: Walmart’s Approach to Health Insurance

Eliminate health insurance age bands

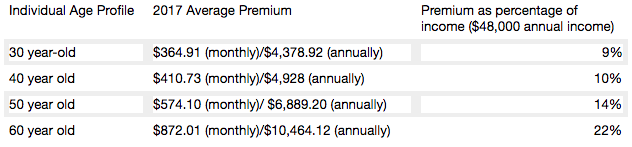

Medicare premiums do not increase with age. Medicare premiums do increase based on income. If someone age 85 is not paying more than someone age 65, why should someone age 50 pay more than someone age 35? Why should a basic health insurance plan work any differently?

Yes, healthcare costs increase with age. Per-person healthcare spending for the 65 and older population was $18,988 in 2012, more than five times higher than spending per child ($3,552) and approximately three times the spending per working-age person ($6,632). From NHE Fact Sheet (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Spending)

Health insurance is currently priced by age bands starting at age 21. Thirty-year-olds have premiums that are 1.135 times more; 40-year- olds pay 1.3 times more; 50-year-olds pay 1.786 more, and 65-year-olds pay 3 times the cost listed. Based on a study by Value Penguin on the Average Cost of Health Insurance (2016).

Private insurance companies are required to offer the same benefits for each lettered Medicare supplement plan, and they do have the ability to charge higher premiums for this coverage. Medicare Supplement Pricing does allow for community-based pricing. And they also do have attained-age-rates where premiums increase as you get older. However, the issue-rated plans have premiums that are lower based on the age which you enroll.

Higher premiums for higher earners

Medicare does require higher-income beneficiaries to pay a larger percentage of the total cost of Part B based on the income you report to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Monthly Part B premiums are equal to 35, 50, 65, or 80 percent of the total cost, depending on what is reported to the IRS. This in keeping with the current progressive tax system (or at least the planned theory of a progressive tax system).

A big Medicare impact from the ACA came via financial improvements it put in place to help the program. It raised a bunch of taxes, including requiring high-income wage earners to pay higher Medicare payroll taxes and stiff premium surcharges for Medicare Part B and D premiums. Health providers and Medicare Advantage insurance plans were also willing to accept lower payment levels from Medicare in exchange for the law’s provisions that would expand their access to more insurance customers.

The individual mandate is not working

Besides being unpopular, the individual mandate is not working. The economics of the ACA are not sound for the long term as there is no balanced offset between how insurance companies typically operate from charging high-risk consumers more than low-risk consumers and providing coverage to all. A planned offset was the penalties on those who didn’t participate. The Supreme Court recognized this as a flaw and Justice Roberts argued that the relative lightness of the penalties was insufficient to compel anyone to buy insurance and, as a result, he considered them to be a “tax” that could be voluntarily avoided rather than a coercive penalty to force commercial activity.

The individual mandate requires nearly all Americans to have health insurance coverage. The individual mandate is an important as it met the critical issue of insurance companies guarding against anti-selection; having health people wait until they need health insurance to sign up. This was meant to be an incentive, however, it is a penalty.

The full penalty for 2016 was $695 per person, $347.50 for each child, up to a maximum of $2,085 -- or 2.5% of your household income, whichever is higher.

It won’t ever work as it’s currently set up since the IRS isn't allowed to collect this penalty the same way it collects on other tax debts. The IRS can deduct penalties you owe from future tax refunds, however, they cannot garnish wages.

The IRS last month quietly reversed a decision to reject tax returns that fail to indicate whether filers had health insurance, received an exemption or paid the penalty. While this has always been key to enforcing the individual mandate, the IRS had been processing returns without this information under the Obama administration.

The IRS attributed the reversal to Trump's executive order that directed agencies to reduce the potential financial burden on Americans.

There are some who feel that since the IRS will accept a tax return without the penalty, that it can be skipped. The IRS has stated that: "Legislative provisions of the ACA law are still in force until changed by the Congress, and taxpayers remain required to follow the law and pay what they may owe,". The agency added that "taxpayers may receive follow-up questions and correspondence at a future date.”

This uncertainty and lack of uniformity is not positive for anyone. And you catch more flies with honey than vinegar. Therefore boosting the benefits is going to work better than a straight out penalty. For insurers, figuring out how to prod younger, healthier Americans to sign up for coverage is critical. As covered elsewhere in this article, there are other, potentially more effective ways to accomplish this. Having a base plan like Medicare will shift some burden directly onto the U.S. Government.

Increasing the burden on the U.S. government and the NFIP

Yes, it’s going to take a lot of planning and conservative assumptions and could be set up along similar lines as the National Flood Insurance Plan (NFIP) created in 1968 by Congress to help provide a means for property owners to financially protect themselves. NFIP is administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which works closely with more than 80 private insurance companies to offer flood insurance to homeowners, renters, and business owners. In order to qualify for flood insurance, the home or business must be in a community that has joined the NFIP and agreed to enforce sound floodplain management standards. Coverage can be purchased through private property and casualty insurance agents. Rates are set nationally and do not differ from company to company or agent to agent. These rates depend on many factors, which include the date and type of construction of your home, along with your building's level of risk. Check out the National Flood Insurance Plan overview. Read answers to common questions about NFIP. There are issues with the NFIP and it is scheduled for reform. The solution to this is to have flexible pricing for private insurance companies such as with Medicare Supplements and Medicare Advantage.

Revise tax credits

Providing tax credits helps low- and moderate-income patients afford health insurance. Premium tax credits protect consumers from rate increases. Marketplace tax credits adjust to match changes in each consumer’s benchmark silver plan premium. Additional consumers are eligible for tax credits. As Marketplace tax credits adjust to match increases in benchmark premiums, some consumers in areas that had low benchmark premiums in 2016 may be newly eligible for tax credits in 2017. Of the nearly 1.3 million HealthCare.gov consumers who did not receive tax credits in 2016, 22 percent have benchmark premiums and incomes in the range that may make them eligible for tax credits in 2017. In addition, an estimated 2.5 million consumers currently paying full price for individual market coverage off-Marketplace have incomes indicating they could be eligible for tax credits.

The Advance Premium Tax Credit is an ACA mechanism for helping some ACA exchange plan users pay for their health coverage. The enrollees estimate when they apply for coverage how much they'll earn in the coming calendar year. The exchange and the IRS use the cost of the coverage and the applicant's income to decide how much the applicant can get. If the applicant qualifies for APTC and buys an exchange plan, the government sends the APTC help to the health coverage issuer while the plan year is still under way. The enrollee does not get to touch the APTC cash.

The ACA currently requires consumers to predict in advance what their incoming will be in the coming year. The majority of consumers apply for individual health insurance during open enrollment for the following year in the preceding end of the year. So they are guessing what their income will be the following year. Then, they even up with the IRS the following year (almost a year and a half later).

Consumers who predict their income be too low and get too much tax credit money are supposed to true up with the IRS when the file their taxes the following spring. The IRS has an easy time getting the money when consumers are supposed to get refunds. It can then deduct the payments from the refunds. When consumers are not getting refunds, or simply fail to file tax returns, the IRS has no easy way to get the cash back.

The exchanges and the IRS also face the problem that some people earn too little to qualify for tax credits but too much to qualify for Medicaid. Those people have an incentive to lie and say their income will be higher than it is likely to be.

And it’s not even close to working, The Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, an agency that monitors the Internal Revenue Service, gave that figure in a new report on how the IRS handled ACA premium tax credit claims for 2014 and 2015. The IRS found that, as of June 30, 2016, the IRS had processed about 5.3 million 2015 returns that included claims for $20.3 billion in tax credits, part of which was $18.9 billion in APTC subsidy help. In June 2015, the IRS had processed 3 million 2014 returns that included claims for $9.8 billion in ACA premium tax credits, including $9 billion in APTC help. For the 2015 returns, which were processed in 2016, IRS program errors led to IRS premium tax credit amount calculation errors for 31,493 returns, TIGTA says. The programming errors led to 16,375 filers getting an average of about $300 too much help each, and 15,118 filers getting an average of $440 too little help each. ACA public exchange program managers send their own tax credit data files to the IRS. The IRS investigates when the gap between what the exchange reports and what the taxpayer reports is big, but not when the gap is small. Because of that policy, the IRS failed to investigate exchange-taxpayer data gaps for 903,488 2015 returns. A majority of the unexamined gaps seemed to hurt taxpayers, rather than helping them, TIGTA says. A review of the APTC gap data suggests that 511,384 affected filers may have missed out on an average of about $1,000 in help each, and that 392,104 may have gotten away with receiving an average of about $300 too much help each, according to TIGTA.

Another issue is that currently, eligibility to receive premium tax credits to purchase exchange coverage is determined by income and whether individuals and families have access to affordable employer coverage. However, many families are not eligible for premium and cost-sharing subsidies to purchase coverage on the exchanges because of the “family glitch,” because determinations about the affordability of employer-sponsored coverage are based on the cost of employee-only coverage, ignoring the cost of family coverage. As a result, these lower-income families are ineligible for subsidies to purchase coverage on exchanges. An estimated 10.5 million adults and children may fall within the family glitch, according to the Department of Health and Human Services’ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Credits would be relative to income and would be lower for those in higher brackets to match our current progressive income tax system. These advance able, refundable tax credits would need to reflect income and location of the health insurance plan. Tax credits would be available to more Americans than under current ACA rules.

Increase subsidies

On the insurer side, risk-based subsidies can help ease the financial pressure posed by enrollees with high health care costs.

Subsidies under the ACA are available to help qualifying Americans pay for their health insurance premiums. These subsidies work on a sliding scale, limiting what you are personally required to contribute toward your premiums to a fixed percentage of your annual income.

The dollar value of your subsidies will depend in part on the cost of the benchmark ACA plan in your area. If the benchmark plan costs more than a certain percentage of your estimated annual income, you can get a subsidy in the amount of the difference. You may then use that subsidy when you buy a qualified ACA health insurance plan. The main factor is your income. You can qualify for a subsidy if you make up to four times the Federal Poverty Level. That's about $47,000 for an individual and $97,000 for a family of four. If you're an individual who makes about $29,000 or less, or a family of four that makes about $60,000 or less, you may qualify for both subsidies.

Subsidies would also need to be fair to older enrollees. Current subsidies under the ACA, allow eligible enrollees to obtain a plan for less than 10% of their income. Having the proper type of subsidy will be crucial. According to the Price-linked subsidies and health insurance mark-ups study from the National Bureau of Economic Research

Senior House Republicans have stated that they expected the federal government to continue paying billions of dollars in subsidies to health insurance companies to keep low-income people covered under the Affordable Care Act for the rest of this year — and perhaps for 2018 as well.The Republican-led House had previously won a lawsuit accusing the Obama administration of unconstitutionally paying the insurance-company subsidies, since no law formally provided the money.Although that decision is on appeal, President Trump could accept the ruling and stop the subsidy payments, which reduce deductibles and co-payments for seven million low-income people. If the payments stopped, insurers — deprived of billions of dollars — would flee the marketplaces, they say. The implosion that Mr. Trump has repeatedly predicted could be hastened. The annual cost of these subsidies is estimated at 7 billion dollars. See “Health Subsidies for Low Earners Will Continue Through 2017, G.O.P. Says”.

Keep the cost-sharing reductions

People who earn up to $29,000 not only get subsidies to pay for their health insurance premiums, they also receive "cost-sharing reduction," or CSR, funds, to make out-of-pocket costs more affordable. Maintaining the CSR payments, which amount to $9 billion to insurers for 2017 is critical. Currently payment of these CSR funds have been halted by the House.

Wait, isn’t the ACA already costing too much?

It turns out that the ACA has turned out to much more cost effective than originally projected. The Congressional Budget Office now projects its cost to be about a third lower than it originally expected, around 0.7 percent of G.D.P. A report from the nonpartisan Urban Institute argues that the A.C.A. is “essentially underfunded,” and would work much better — in particular, it could offer policies with much lower deductibles — if it provided somewhat more generous subsidies. The report’s recommendations would cost around 0.2 percent of G.D.P.

Use a value-added tax (VAT) or other sales tax

Use the current Medicare Payroll Tax and supplement it with a sales/value added tax, that way everyone pays for the plan who would use it - underground economy, cash economy and those don’t file income tax returns This would encourage more people to file income tax returns to get the proposed (current) credit. This would be a boost to the US economy and the Federal Budget as this missed income tax revenue while reducing resources from the IRS in finding those who don’t file income tax returns.

Trade-offs needs to made and the only way to do so is to ensure that everyone has a baseline of benefits . Adding a value added tax/sales tax to help finance it would ensure that that plan is not solely supported by those who pay income, the plan is supported by anyone who makes a purchase, as let's face it, some people don't report income. Tax credits would still be available to those who qualify based on income. This would also encourage more people to file tax returns to make sure they received the credit if eligible. In fact, give everyone who files a $100 credit for their health insurance if they file, I'll bet the number of income tax returns would rise significantly.

Stop tax evasion

If all tax evasion were stopped, this alone could pay for health care. Following are some stats on tax evasion from The National Tax Research Committee released by Americans for Fair Taxation: Estimated Future Tax Evasion under the Income Tax and Prospects for Tax Evasion under the FairTax: New Perspectives

To enable the federal government to raise the same level of revenue it would collect if all taxpayers were to report their income and pay their taxes in full, the income tax system, in effect, assesses the average household an annual “surtax” that varies from $4,276 under the most conservative scenario, to $8,526 based on the more likely to occur historical evasion trends. The IRS estimates that almost 40% of the public are out of compliance with the present tax system, mostly unintentionally due to the enormous complexity of the present system. These IRS figures do not include taxes lost on illegal sources of income with a criminal economy estimated at a trillion dollars.

Market stabilization - Risk-sharing modifications

Diversifying the risk pool and keeping the market stable is a critical factor in maintaining viability for insurance companies. The ACA included 3 components to help accomplish this goal:

Average cost for an average annual worker and employer contributions for single and family (Kaiser Family Foundation): Single coverage, all firms: total $6,445 (employer share, $5,306; employee share, $1,129). Family Coverage: total $18,142 (employer share: $12,865, employee share: $5,277). In 2017, the maximum allowable cost-sharing (including out-of-pocket costs for deductibles, co-payments and co-insurance) is $7,150 for self-only coverage and $14,300 for families.

Most marketplace consumers have affordable options. More than 7 in 10 (72%) of current enrollees can find a plan for $75 or less in premiums per month, after applicable tax credits in 2017. Nearly 8 in 10 (77%) can find a plan for $100 or less in premiums per month, after applicable tax credits in 2017.

Two recent Kaiser Health Tracking Polls looked at Americans' current experience with and worries about healthcare costs, including their ability to afford premiums and deductibles. For the most part, the majority of the public does not have difficulty paying for care, but significant minorities do, and even more worry about their ability to afford care in the future. Four in ten (43%) adults with health insurance say they have difficulty affording their deductible, and roughly a third say they have trouble affording their premiums and other cost sharing; all shares have increased since 2015. Among people with health insurance, one in five (20%) working-age Americans report having problems paying medical bills in the past year that often cause serious financial challenges and changes in employment and lifestyle.

Even for those who may not have had difficulty affording care or paying medical bills, there is still a widespread worry about being able to afford needed healthcare services, with half of the public expressing worry about this. Healthcare-related worries and problems paying for care are particularly prevalent among the uninsured, individuals with lower incomes and those in poorer health. Women and members of racial minority groups are also more likely than their peers to report these issues.

Making health insurance affordable again

Medicare Part A is currently available with no premium if you or your spouses paid Medicare taxes. Medicare Part A can continue to be offered for free to those who pay taxes and for those who qualify for Medicaid.

Medicare Part B premiums are subsidized with the government paying a substantial portion (about 75%) of the Part B premium, and the beneficiary paying the remaining 25%. Premiums are subsidized, with the gross total monthly premium being $134. This amount is reduced to $109 on average for those on Social Security. Depending on your income, the premium can increase to $428.60 monthly. View information on Part B premiums here.

Medicare prescription drug coverage helps pay for your prescription drugs. For most beneficiaries, the government pays a major portion of the total costs for this coverage, and the beneficiary pays the rest. Prescription drug plan costs vary depending on the plan, as does whether you get extra help with your portion of the Medicare prescription drug coverage costs. Higher earners pay more.

Beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage typically pay monthly premiums for additional benefits covered by their plan, in addition to the Part B premium. Kaiser Family Foundation figures.

How is Medicare financed?

Medicare Part A is financed primarily through a 2.9% tax on earnings paid by employers and employees (1.45% each) (accounting for 88% of Part A revenue). Higher-income taxpayers (more than $200,000/individual and $250,000/couple) pay a higher payroll tax on earnings (2.35%). To pay for Part A, taxes will need to go up, but the trade-off is that premiums for the supplemental coverage will be less because it covers less - net impact to the consumer is zero.

Medicare Part B is financed through general revenues (73%), beneficiary premiums (25%), and interest and other sources (2%). Beneficiaries with annual incomes over $85,000/individual or $170,000/couple pay a higher, income-related Part B premium, ranging from 35% to 80%. The ACA froze the income thresholds through 2019, and, beginning in 2020, the income thresholds will once again be indexed to inflation, based on their levels in 2019 (a provision in the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015). As a result, the number and share of beneficiaries paying income-related premiums will increase as the number of people on Medicare continues to grow in future years and as their incomes rise. Premiums would be less than under current individual insurance plans because certain essential benefits would be covered by the expanded Medicare Part A.

Medicare Part D is financed by general revenues (77%), beneficiary premiums (14%) and state payments for dually eligible beneficiaries (10%). As with Part B, higher-income enrollees pay a larger share of the cost of Part D coverage.

Medicare Part C (The Medicare Advantage program) is not separately financed. Medicare Advantage plans such as HMOs and PPOs cover all Part A, Part B and (typically) Part D benefits. Beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans typically pay monthly premiums for additional benefits covered by their plan in addition to the Part B premium.

From Kaiser Foundation: The Facts on Medicare Spending and financing worksheet.

The public need for increased plan choice and market stability

Health insurance exchanges haven’t worked so far. Currently, there are only 12 state-based marketplaces; five state-based marketplace-federal platforms, six state-partnership marketplaces; and 28 federally facilitated marketplaces. A list of State Health Insurance Marketplace types can be be found on the Kaiser Family Foundation website.

The Congressional Budget Office said that although the ACA’s markets are “stable in most areas,” about 42% of those buying coverage on Obamacare’s exchanges had just one or two insurers to pick from for this year. Currently, one in three counties has just one insurer in the local market, significantly less choice than the one in 14 counted last year, according to the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation. And five states have a single insurer: Alabama, Alaska, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Wyoming. Moving to a Medicare-based system would mean that, if an insurance company decides to leave a county or state, the residents still have access to health insurance. There are parts of Tennessee where there may not be any exchange insurance options for 2018. And Oklahoma’s insurance regulator warned last week that his state’s lone carrier may quit the market.

With issues facing the Affordable Care Act on subsidies, Medicaid expansion and other potential changes, consumers may end up with few choices as insurance companies decide to not participate in the exchanges in the future. Humana has announced that it will drop out of the 11 states where it offers ACA plans. Other major insurance companies, including Anthem, Aetna and Molina Healthcare, have warned that they can’t commit to participating in the ACA exchanges in 2018.

Medi-gap supplements and Medicare Advantage will boost choice. Medicare Advantage has proven to be popular, and enrollment is expected to increase to all-time high of 18.5 million Medicare beneficiaries. In 2017, this will represent about 32% of Medicare beneficiaries. Typical Medicare Advantage plan providers offer managed care plans.

Access to the Medicare Advantage program remains nearly universal, with 99% of Medicare beneficiaries having access to a health plan in their area. Access to supplemental benefits, such as dental and vision benefits, continues to grow. More than 94% of Medicare beneficiaries have access to a $0 premium Medicare Advantage plan. 100% of Medicare beneficiaries – including Medicare Advantage enrollees – have access to recommended Medicare-covered preventive services at zero cost sharing.

Consumers have access to information to improve plan choice. Medicare beneficiaries are allowed a one-time opportunity to switch to a five-star Medicare Advantage plan or prescription drug plan in their area any time during the year. Medicare has a low-performing icon on Medicare.gov so beneficiaries know which plans are not performing well. Medicare Advantage plan sponsors are also required spend at least 85% of premiums on quality and care delivery and not on overhead, profit or administrative costs.

According to a recent fact sheet from CMS.gov, Moving Medicare Advantage and Part D Forward: Some counties have low Medicare Advantage penetration rates because the number of hospitals and doctors is too low for use of a managed care network to make much sense. This mirrors some of the reasons why there are few marketplace options in certain counties and state and is exactly why there needs to be a plan available through the federal government, as with the current Medicare Parts B & D.

When retirees are unhappy with Medicare Advantage plan provider directories, they typically combine traditional Medicare coverage with Medicare supplement insurance, or Medigap coverage. Retirees using Medigap coverage with traditional Medicare can use any provider that takes Medicare.

Consumers are better able to control their Medicare Advantage Plan (Part C) premiums by choosing a plan without a monthly premium, having a plan that pays part of Medicare Part B, having a deductible, choosing a copayment (coinsurance) amount, choosing the type of health services, setting their limit on annual out-of-pocket expenses and choosing whether they go to a doctor or other medical service supplier who accepts assignment (from Medicare).

Balancing the risk pool

The risk pool must be sufficiently large to take advantage of the law of big numbers. Insurance companies reflect healthcare costs, and their mission is to spread the risk and be balanced. If the risk pool is unbalanced by covering too many sick people and not enough healthy people, the insurance company will have higher claims and will need to collect higher premiums. When this happens, healthier individuals are usually the first to drop coverage, which they feel is not needed, which leaves a growing proportion of “less healthy” individuals. At some point, the imbalance becomes unsustainable, and the carriers exit the market entirely.

The only reason healthy people buy health insurance is that they know that if they wait until they get really sick no insurance company will sell them a policy. The same principle holds true for all insurance products. You can’t buy auto insurance after you get into an accident. You can’t buy life insurance at a reasonable cost after your doctor has given you six months to live. The fact that your car is already wrecked, or your arteries already clogged, are pre-existing conditions that no insurance company would be expected to ignore.

Allowing voters the low-cost option to buy health insurance after they actually need it is very popular. It’s like promising motorists they can stop paying their monthly auto insurance premium and just buy a policy after they have an accident. If the government were to require this, all auto insurance companies would quickly go out of business (unless they were bailed out by the government).

Contrary to belief, younger people (millennials) do want want health insurance and consider it a top life priority, according to a study from research firm Benson Strategy Group. Eighty-six percent of millennials are insured, and 85% said it is "absolutely essential" or "very important" to have coverage, according to the survey. Researchers said most millennials get their insurance through an employer (39%) or Medicaid (20%).

Shifting work force and ending the current group health insurance market

The U.S. work force is shifting, with fewer Americans working at large employers and being covered by group health insurance. Americans are moving more to being “gig” employees, freelancers/consultants, part-time employees, job movement, cash employees and seasonal employees and continuing to start businesses.

For employers, counting employees for purposes of ACA compliance seems to be an expensive nightmare.

The size of your employer is a major factor on if health insurance is offered: 96% of firms with 100 or more employees offered health insurance, 89% of employers between 50 and 99 employees offer health insurance, while 53% of employees with three to 49 workers offered health insurance; the average is 56% of employers offering coverage. So unless you work at a big firm, you can't count on health insurance anyway. And dependent on the size of the firm, there is no guarantee that it will offer coverage to spouses, dependents or domestic partners.

Even those with group health insurance received less value than historically. According to a recent LinkedIn study (2/2017), a total of 63% of respondents indicated that their healthcare benefits were either more expensive or stingier than in the previous year, and 40% saw both an increase in premium costs as well as higher out-of-pocket copays and deductibles when they used their health plans.

In a survey (2/2017), nearly one in five LinkedIn members in the U.S. (or 19%) indicated that health insurance has been their primary reason for taking, leaving or keeping a job.

If health insurance is available as proposed through individual, portable insurance plans, there will no longer be employer health insurance programs. Excluding premiums from taxes was worth about $250 billion in forgone tax revenue in 2013, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Some health economists have argued that the exemption artificially drives up health spending. Employer-provided health benefits, often worth thousands of dollars a year, aren’t taxed as wages are. People who have to buy coverage on their own don’t enjoy the same tax advantage. Currently, employers do offer supplemental benefits to their employees that they often pay at least part of the premium.

See also: Walmart’s Approach to Health Insurance

Eliminate health insurance age bands

Medicare premiums do not increase with age. Medicare premiums do increase based on income. If someone age 85 is not paying more than someone age 65, why should someone age 50 pay more than someone age 35? Why should a basic health insurance plan work any differently?

Yes, healthcare costs increase with age. Per-person healthcare spending for the 65 and older population was $18,988 in 2012, more than five times higher than spending per child ($3,552) and approximately three times the spending per working-age person ($6,632). From NHE Fact Sheet (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Spending)

Health insurance is currently priced by age bands starting at age 21. Thirty-year-olds have premiums that are 1.135 times more; 40-year- olds pay 1.3 times more; 50-year-olds pay 1.786 more, and 65-year-olds pay 3 times the cost listed. Based on a study by Value Penguin on the Average Cost of Health Insurance (2016).

Private insurance companies are required to offer the same benefits for each lettered Medicare supplement plan, and they do have the ability to charge higher premiums for this coverage. Medicare Supplement Pricing does allow for community-based pricing. And they also do have attained-age-rates where premiums increase as you get older. However, the issue-rated plans have premiums that are lower based on the age which you enroll.

Higher premiums for higher earners

Medicare does require higher-income beneficiaries to pay a larger percentage of the total cost of Part B based on the income you report to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Monthly Part B premiums are equal to 35, 50, 65, or 80 percent of the total cost, depending on what is reported to the IRS. This in keeping with the current progressive tax system (or at least the planned theory of a progressive tax system).

A big Medicare impact from the ACA came via financial improvements it put in place to help the program. It raised a bunch of taxes, including requiring high-income wage earners to pay higher Medicare payroll taxes and stiff premium surcharges for Medicare Part B and D premiums. Health providers and Medicare Advantage insurance plans were also willing to accept lower payment levels from Medicare in exchange for the law’s provisions that would expand their access to more insurance customers.

The individual mandate is not working

Besides being unpopular, the individual mandate is not working. The economics of the ACA are not sound for the long term as there is no balanced offset between how insurance companies typically operate from charging high-risk consumers more than low-risk consumers and providing coverage to all. A planned offset was the penalties on those who didn’t participate. The Supreme Court recognized this as a flaw and Justice Roberts argued that the relative lightness of the penalties was insufficient to compel anyone to buy insurance and, as a result, he considered them to be a “tax” that could be voluntarily avoided rather than a coercive penalty to force commercial activity.

The individual mandate requires nearly all Americans to have health insurance coverage. The individual mandate is an important as it met the critical issue of insurance companies guarding against anti-selection; having health people wait until they need health insurance to sign up. This was meant to be an incentive, however, it is a penalty.

The full penalty for 2016 was $695 per person, $347.50 for each child, up to a maximum of $2,085 -- or 2.5% of your household income, whichever is higher.

It won’t ever work as it’s currently set up since the IRS isn't allowed to collect this penalty the same way it collects on other tax debts. The IRS can deduct penalties you owe from future tax refunds, however, they cannot garnish wages.

The IRS last month quietly reversed a decision to reject tax returns that fail to indicate whether filers had health insurance, received an exemption or paid the penalty. While this has always been key to enforcing the individual mandate, the IRS had been processing returns without this information under the Obama administration.

The IRS attributed the reversal to Trump's executive order that directed agencies to reduce the potential financial burden on Americans.

There are some who feel that since the IRS will accept a tax return without the penalty, that it can be skipped. The IRS has stated that: "Legislative provisions of the ACA law are still in force until changed by the Congress, and taxpayers remain required to follow the law and pay what they may owe,". The agency added that "taxpayers may receive follow-up questions and correspondence at a future date.”

This uncertainty and lack of uniformity is not positive for anyone. And you catch more flies with honey than vinegar. Therefore boosting the benefits is going to work better than a straight out penalty. For insurers, figuring out how to prod younger, healthier Americans to sign up for coverage is critical. As covered elsewhere in this article, there are other, potentially more effective ways to accomplish this. Having a base plan like Medicare will shift some burden directly onto the U.S. Government.

Increasing the burden on the U.S. government and the NFIP

Yes, it’s going to take a lot of planning and conservative assumptions and could be set up along similar lines as the National Flood Insurance Plan (NFIP) created in 1968 by Congress to help provide a means for property owners to financially protect themselves. NFIP is administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which works closely with more than 80 private insurance companies to offer flood insurance to homeowners, renters, and business owners. In order to qualify for flood insurance, the home or business must be in a community that has joined the NFIP and agreed to enforce sound floodplain management standards. Coverage can be purchased through private property and casualty insurance agents. Rates are set nationally and do not differ from company to company or agent to agent. These rates depend on many factors, which include the date and type of construction of your home, along with your building's level of risk. Check out the National Flood Insurance Plan overview. Read answers to common questions about NFIP. There are issues with the NFIP and it is scheduled for reform. The solution to this is to have flexible pricing for private insurance companies such as with Medicare Supplements and Medicare Advantage.

Revise tax credits

Providing tax credits helps low- and moderate-income patients afford health insurance. Premium tax credits protect consumers from rate increases. Marketplace tax credits adjust to match changes in each consumer’s benchmark silver plan premium. Additional consumers are eligible for tax credits. As Marketplace tax credits adjust to match increases in benchmark premiums, some consumers in areas that had low benchmark premiums in 2016 may be newly eligible for tax credits in 2017. Of the nearly 1.3 million HealthCare.gov consumers who did not receive tax credits in 2016, 22 percent have benchmark premiums and incomes in the range that may make them eligible for tax credits in 2017. In addition, an estimated 2.5 million consumers currently paying full price for individual market coverage off-Marketplace have incomes indicating they could be eligible for tax credits.

The Advance Premium Tax Credit is an ACA mechanism for helping some ACA exchange plan users pay for their health coverage. The enrollees estimate when they apply for coverage how much they'll earn in the coming calendar year. The exchange and the IRS use the cost of the coverage and the applicant's income to decide how much the applicant can get. If the applicant qualifies for APTC and buys an exchange plan, the government sends the APTC help to the health coverage issuer while the plan year is still under way. The enrollee does not get to touch the APTC cash.

The ACA currently requires consumers to predict in advance what their incoming will be in the coming year. The majority of consumers apply for individual health insurance during open enrollment for the following year in the preceding end of the year. So they are guessing what their income will be the following year. Then, they even up with the IRS the following year (almost a year and a half later).

Consumers who predict their income be too low and get too much tax credit money are supposed to true up with the IRS when the file their taxes the following spring. The IRS has an easy time getting the money when consumers are supposed to get refunds. It can then deduct the payments from the refunds. When consumers are not getting refunds, or simply fail to file tax returns, the IRS has no easy way to get the cash back.

The exchanges and the IRS also face the problem that some people earn too little to qualify for tax credits but too much to qualify for Medicaid. Those people have an incentive to lie and say their income will be higher than it is likely to be.

And it’s not even close to working, The Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, an agency that monitors the Internal Revenue Service, gave that figure in a new report on how the IRS handled ACA premium tax credit claims for 2014 and 2015. The IRS found that, as of June 30, 2016, the IRS had processed about 5.3 million 2015 returns that included claims for $20.3 billion in tax credits, part of which was $18.9 billion in APTC subsidy help. In June 2015, the IRS had processed 3 million 2014 returns that included claims for $9.8 billion in ACA premium tax credits, including $9 billion in APTC help. For the 2015 returns, which were processed in 2016, IRS program errors led to IRS premium tax credit amount calculation errors for 31,493 returns, TIGTA says. The programming errors led to 16,375 filers getting an average of about $300 too much help each, and 15,118 filers getting an average of $440 too little help each. ACA public exchange program managers send their own tax credit data files to the IRS. The IRS investigates when the gap between what the exchange reports and what the taxpayer reports is big, but not when the gap is small. Because of that policy, the IRS failed to investigate exchange-taxpayer data gaps for 903,488 2015 returns. A majority of the unexamined gaps seemed to hurt taxpayers, rather than helping them, TIGTA says. A review of the APTC gap data suggests that 511,384 affected filers may have missed out on an average of about $1,000 in help each, and that 392,104 may have gotten away with receiving an average of about $300 too much help each, according to TIGTA.

Another issue is that currently, eligibility to receive premium tax credits to purchase exchange coverage is determined by income and whether individuals and families have access to affordable employer coverage. However, many families are not eligible for premium and cost-sharing subsidies to purchase coverage on the exchanges because of the “family glitch,” because determinations about the affordability of employer-sponsored coverage are based on the cost of employee-only coverage, ignoring the cost of family coverage. As a result, these lower-income families are ineligible for subsidies to purchase coverage on exchanges. An estimated 10.5 million adults and children may fall within the family glitch, according to the Department of Health and Human Services’ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Credits would be relative to income and would be lower for those in higher brackets to match our current progressive income tax system. These advance able, refundable tax credits would need to reflect income and location of the health insurance plan. Tax credits would be available to more Americans than under current ACA rules.

Increase subsidies

On the insurer side, risk-based subsidies can help ease the financial pressure posed by enrollees with high health care costs.

Subsidies under the ACA are available to help qualifying Americans pay for their health insurance premiums. These subsidies work on a sliding scale, limiting what you are personally required to contribute toward your premiums to a fixed percentage of your annual income.

The dollar value of your subsidies will depend in part on the cost of the benchmark ACA plan in your area. If the benchmark plan costs more than a certain percentage of your estimated annual income, you can get a subsidy in the amount of the difference. You may then use that subsidy when you buy a qualified ACA health insurance plan. The main factor is your income. You can qualify for a subsidy if you make up to four times the Federal Poverty Level. That's about $47,000 for an individual and $97,000 for a family of four. If you're an individual who makes about $29,000 or less, or a family of four that makes about $60,000 or less, you may qualify for both subsidies.

Subsidies would also need to be fair to older enrollees. Current subsidies under the ACA, allow eligible enrollees to obtain a plan for less than 10% of their income. Having the proper type of subsidy will be crucial. According to the Price-linked subsidies and health insurance mark-ups study from the National Bureau of Economic Research

Senior House Republicans have stated that they expected the federal government to continue paying billions of dollars in subsidies to health insurance companies to keep low-income people covered under the Affordable Care Act for the rest of this year — and perhaps for 2018 as well.The Republican-led House had previously won a lawsuit accusing the Obama administration of unconstitutionally paying the insurance-company subsidies, since no law formally provided the money.Although that decision is on appeal, President Trump could accept the ruling and stop the subsidy payments, which reduce deductibles and co-payments for seven million low-income people. If the payments stopped, insurers — deprived of billions of dollars — would flee the marketplaces, they say. The implosion that Mr. Trump has repeatedly predicted could be hastened. The annual cost of these subsidies is estimated at 7 billion dollars. See “Health Subsidies for Low Earners Will Continue Through 2017, G.O.P. Says”.

Keep the cost-sharing reductions

People who earn up to $29,000 not only get subsidies to pay for their health insurance premiums, they also receive "cost-sharing reduction," or CSR, funds, to make out-of-pocket costs more affordable. Maintaining the CSR payments, which amount to $9 billion to insurers for 2017 is critical. Currently payment of these CSR funds have been halted by the House.

Wait, isn’t the ACA already costing too much?

It turns out that the ACA has turned out to much more cost effective than originally projected. The Congressional Budget Office now projects its cost to be about a third lower than it originally expected, around 0.7 percent of G.D.P. A report from the nonpartisan Urban Institute argues that the A.C.A. is “essentially underfunded,” and would work much better — in particular, it could offer policies with much lower deductibles — if it provided somewhat more generous subsidies. The report’s recommendations would cost around 0.2 percent of G.D.P.

Use a value-added tax (VAT) or other sales tax

Use the current Medicare Payroll Tax and supplement it with a sales/value added tax, that way everyone pays for the plan who would use it - underground economy, cash economy and those don’t file income tax returns This would encourage more people to file income tax returns to get the proposed (current) credit. This would be a boost to the US economy and the Federal Budget as this missed income tax revenue while reducing resources from the IRS in finding those who don’t file income tax returns.

Trade-offs needs to made and the only way to do so is to ensure that everyone has a baseline of benefits . Adding a value added tax/sales tax to help finance it would ensure that that plan is not solely supported by those who pay income, the plan is supported by anyone who makes a purchase, as let's face it, some people don't report income. Tax credits would still be available to those who qualify based on income. This would also encourage more people to file tax returns to make sure they received the credit if eligible. In fact, give everyone who files a $100 credit for their health insurance if they file, I'll bet the number of income tax returns would rise significantly.

Stop tax evasion

If all tax evasion were stopped, this alone could pay for health care. Following are some stats on tax evasion from The National Tax Research Committee released by Americans for Fair Taxation: Estimated Future Tax Evasion under the Income Tax and Prospects for Tax Evasion under the FairTax: New Perspectives

To enable the federal government to raise the same level of revenue it would collect if all taxpayers were to report their income and pay their taxes in full, the income tax system, in effect, assesses the average household an annual “surtax” that varies from $4,276 under the most conservative scenario, to $8,526 based on the more likely to occur historical evasion trends. The IRS estimates that almost 40% of the public are out of compliance with the present tax system, mostly unintentionally due to the enormous complexity of the present system. These IRS figures do not include taxes lost on illegal sources of income with a criminal economy estimated at a trillion dollars.

Market stabilization - Risk-sharing modifications

Diversifying the risk pool and keeping the market stable is a critical factor in maintaining viability for insurance companies. The ACA included 3 components to help accomplish this goal:

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Tony Steuer connects consumers and insurance agents by providing "Insurance Literacy Answers You Can Trust." Steuer is a recognized authority on life, disability and long-term care insurance literacy and is the founder of the Insurance Literacy Institute and the Insurance Quality Mark and has recently created a best practices standard for insurance agents: the Insurance Consumer Bill of Rights.

Although driverless cars will become mainstream in more than a decade, insurance executives should start thinking about certain issues now.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

As Congress considers another healthcare bill, the conversation continues to be about insurance, even though a form of reinsurance could solve many of the problems we face as a nation. The money for what I call "transparent health reinsurance" is already even in the various bills that Congress has considered; the more than $100 billion that has been designated for stabilizing healthcare insurance in the individual states would simply have to be redirected.

See also: Transparent Reinsurance for Health

Transparent health reinsurance enables more people to receive better health care at less cost. As I wrote on this site in May 2016, “Transparent reinsurance programs could emerge as significant opportunities for healthcare providers, issuers, reinsurers, technology innovators and regulators to address health insurance.” Transparent health reinsurance, pioneered by Marketcore, creates robust technologies that enable better, patient-centered health care through predictive analytics.

“Sharing information generates participation and creates cross-network efficiencies to enhance quality, improve delivery and reduce costs,” remarks Constance Erlanger, Marketcore's CEO. “For healthcare insurers and providers, there are two key value-adds. First, the technologies incorporate any and all specific features a state and insurers in its jurisdiction may or may not include in state healthcare markets. Second, risk lenses clarify quality, delivery, outcome and cost across the 56 states and territories for transparent health insurance and healthcare services. Such robust information symmetry could rationalize healthcare insurance, quality and delivery. Such technologies, created by Marketcore, are already in development for bankers and insurers in multiple markets for complex risk assessments to finance recoveries from large-scale natural disasters.”

Everyone experiences strategic and financial advantage

Transparent health reinsurance supports these innovations by providing incentives that tackle the “widespread lack of transparency about both the costs and the effectiveness of treatments,” as Dr. Brian Holzer calls for in a timely article.

Any state could create a high-claim reinsurance pool managed by a recognized reinsurance operative. With supervision by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), a state insurance commission or its designee could invite qualified firms to function as a recognized reinsurer. These recognized reinsurers would work with qualified, innovative health service providers that demonstrate abilities to improve health outcomes at reduced expense. The reinsurers would be part of a matrix solution, where some firms provide health management solutions, while others provide disease- specific solutions and others provide innovations in treatment.

A state could, perhaps, elect to focus on the largest drivers of healthcare costs in its jurisdiction, such as chronically ill individuals or those with acute conditions that are difficult to predict. Due to the technology’s granularity and clarity, a state could just as readily specify participation among all issuers for any plan being offered in its jurisdiction, including every participant in every plan or defining reinsurance participation for individuals with chronic conditions in employee-sponsored or state-managed plans. Or, states could fund a high-claim reinsurance pool with a payment per covered life, preferably covering everyone in the state, thus lowering the per-life charge.

Pending state decision-making, employers would have the right to move employees into this pool, and would want to do so if it was clear that the innovative approaches reduced costs while improving health outcomes. Clearly, the lowest per-capita contributions would occur with the widest participation. If a state targets the largest cost drivers, reinsurer and insurers would then work together to assign "high-claim" individuals to reinsurance pools once those individuals cross a defined expense threshold. Each individual would be assigned to one or more innovators under contract to deliver better health outcomes at reduced costs. An innovative tracking mechanism would measure and rank outcomes and savings. Crowd-sourced information would drive confidence scores. Burgeoning digital applications managing chronic illness would yield voluminous, timely data, and blockchain technologies afford accountability.

Scoring would rank service providers and eliminate failed providers. A state insurance commission or its designee as reinsurer could manage transparent health reinsurance as states reach management decisions with stabilization funds. A single designated entity could oversee a system that would reward innovative, successful healthcare delivery and quality.

To that end, participating firms would be for proposals detailing expected improved health outcomes and costs. The technology leverages continuing achievement. Some studies indicate 40% cost reductions for some chronic conditions. By adding transparency to these achievements, the technology scales to yield much lower overall healthcare costs, healthier populations and stabilized or lower insurer premiums.

At the end of each year, a new reinsurance pool would be formulated with adjustments based on actual experiences. If the previous pool ended up in surplus, a portion of that surplus would be retained in reserve, and any remaining amount could be returned to individuals, providers or both. If the previous pool ended up in deficit, the reinsurer could choose to fund that, with contributions in the following year meant to provide for recovery.

Several states could decide to form an umbrella reinsurance pool to cover some or all of their high-claim individuals. All activities focus on improving health outcomes at reduced costs. No state residents are asked to fend for themselves. States are encouraged to develop innovative firms. Overall health of state residents should improve, which would lead to a healthier economy. Ultimately, state-related healthcare costs would decline. In the process, transparent health reinsurance would animate highly profitable growth for corporations with domain strengths in mobile data, operating systems, search and social media.

These firms could tap data and metadata markets by creating valuable, time-sensitive risk information and metrics. (With such robust technologies, privacy matters, and all platforms are HIPAA-compliant.) As healthcare reform faltered in the Senate, Govs. John Kasich (R-Iowa) and John Hickenlooper (D-Colorado) called for bipartisan solutions. Technologies and tools are at hand to make those solutions possible.

“If I am for myself alone, who will be for me? If not now, when?” the prophet Hillel remarked centuries ago.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Hugh Carter Donahue is expert in market administration, communications and energy applications and policies, editorial advocacy and public policy and opinion. Donahue consults with regional, national and international firms.

The status quo is far from ideal, but Strategic Relationship Management provides a strong and effective framework.

Examples of strategic partnership models include:

Examples of strategic partnership models include:

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Bruce Brodie is a managing director for PwC's insurance advisory practice focusing on insurance operations and IT strategy, new IT operating models and IT functional transformation. Brodie has 30 years of experience in the industry and has held a number of leadership positions in the insurance and consulting world.

Everywhere you look, companies are using video as a major part of their marketing strategies. Agency owners can't stay on the sidelines.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

"Single-pricing" is the real issue. In other words, we're having the wrong debate, creating a huge distraction.

“Universal health coverage is defined as ensuring that all people have access to needed promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative health services, of sufficient quality to be effective, while also ensuring that people do not suffer financial hardship when paying for these services. Universal health coverage has therefore become a major goal for health reform in many countries and a priority objective of WHO.”Terms like “universal healthcare,” “Medicare for All,” and “single-payer” are typically substituted for universal coverage as if they all mean the same thing and everyone understands the reference. They don’t, and the big distinctions are critical for any debate. Payment and coverage are definitely connected, but that connection can (and should) be simple and transparent, not complex and opaque. Universal coverage is that simplicity and transparency. What we have is tiered coverage designed to support tiered pricing. It's not just complex for everyone, it's totally opaque. Medicare, Medicaid, VA, Indian Health Services, employer-sponsored insurance, Obamacare and the uninsured are all different tiers of coverage — all with different pricing. That works well to maximize revenue and profits, but the enormous sacrifice to this design is safety, quality and equality. A big myth surrounding the debate is that our system is just broken. It’s not. It’s working exactly as designed, and we need a different system design based on the core principle of universal coverage. See also: Healthcare Needs a Data Checkup Obviously, how universal coverage is paid for (either single- or multi-payer, delivered through government or privately owned industries) is a critical debate, but who qualifies for coverage (and under what terms) shouldn’t be. There are only three big arguments against universal coverage — clinical, fiscal and moral — and they all fail. The clinical evidence alone isn’t dazzling, but it is compelling. As MedPage Today noted last week:

“There are a lot more studies covered in Woolhandler and Himmelstein's paper, but they all suggest roughly the same thing–that insurance has a modest, but real, effect on all-cause mortality. Something to the tune of a 20% relative reduction in death compared to being uninsured.”That’s just the clinical evidence, but healthcare is really expensive, so health coverage is inseparable from payment — which, of course, is the fiscal or economic argument. As a country, we've been arguing, fussing and fighting over the economics of healthcare for decades — and we're likely to continue for years to come — but the following chart is the only proof we need that we're not just on the wrong clinical trajectory, we're on the wrong fiscal one, as well. [caption id="attachment_26817" align="alignnone" width="570"]

Creative Commons License by author Max Roser[/caption]

Our system design is the death spiral — not Obamacare. Of course, policy wonks and politicians love to confuse the debate with a heavy focus on the y-axis of life expectancy. The general argument here is that the data around life expectancy is too variable around the world, so it’s all wrong. By extension, the argument goes, the whole chart must be wrong, but I’ve seen no dispute with the x-axis because the math is bone simple. Take our (estimated) National Health Expenditure for 2017 ($3.539 trillion, from CMS) and divide that by our current population (325,355,000, from the Census Bureau). The result is a whopping $10,877 per capita spending just on healthcare this year (the chart only goes to $9,000 in 2014).