How Does GEICO Save Customers 15%?

Easy question, simple answer: They don’t. The implication is that an agent "skims" 15% commission off the top, but that's very wrong.

Easy question, simple answer: They don’t. The implication is that an agent "skims" 15% commission off the top, but that's very wrong.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

William C. Wilson, Jr., CPCU, ARM, AIM, AAM is the founder of Insurance Commentary.com. He retired in December 2016 from the Independent Insurance Agents & Brokers of America, where he served as associate vice president of education and research.

Some argue that justifying usage-based insurance for autos requires huge improvement in loss ratios, but they miss key points.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Deke Phillips is principal consultant-telematics for CCC Information Services. Phillips is responsible for helping auto insurance companies develop and deploy telematics and usage-based insurance programs, including the integration of telematics data into underwriting and claim workflows.

Recent concerns about the accuracy of big data used in insurance applications reflects badly outdated thinking.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Andrew Robinson is an insurance industry executive and thought leader. He is an executive in residence at Oak HC/FT, a premier venture growth equity fund investing in healthcare information and services and financial services technology.

Why do customers commit $80 billion in insurance fraud each year? What are they telling us -- and can we rewire how they think about our industry?

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Maria Ferrante-Schepis is the managing principal of insurance and financial services innovation at Maddock Douglas.

CFOs must recognize that healthcare is a capital allocation strategy—it needs the supervision of an executive with P&L responsibility.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Craig Lack is "the most effective consultant you've never heard of," according to Inc. magazine. He consults nationwide with C-suites and independent healthcare broker consultants to eliminate employee out-of-pocket expenses, predictably lower healthcare claims and drive substantial revenue.

Just 42% of insurers support a seamless user experience. They need to emphasize their omnichannel offerings, like chatbots.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

John Cammarata is the insurance transformation leader at PointSource. As the lead for architecture and development at PointSource, Cammarata is continually identifying ways that technology and digital engagement patterns are the catalysts behind disruption in the insurance industry.

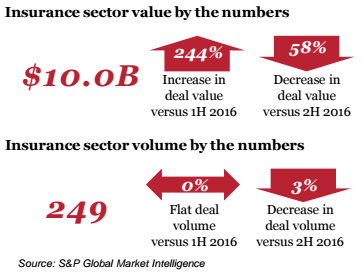

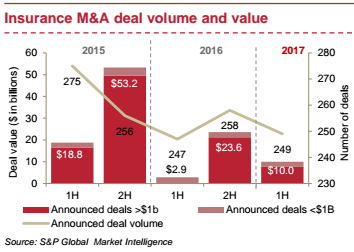

Deal value in the U.S. insurance sector more than tripled to $10 billion in the first half of 2017, compared with $2.9 billion in the first half of 2016.

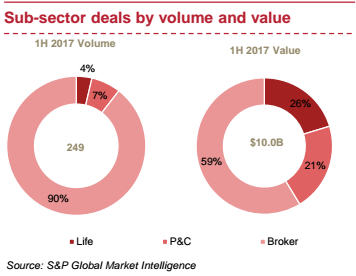

Highlights of 1H 2017 deal activity

Evolving nature of deals in 1H 2017

There were only three announced deals valued in excess of $1 billion, amounting to a total of $7.8 billion, in the first half of 2017:

Highlights of 1H 2017 deal activity

Evolving nature of deals in 1H 2017

There were only three announced deals valued in excess of $1 billion, amounting to a total of $7.8 billion, in the first half of 2017:

Deals that did not meet our S&P screening, but are notable for their scale or intent, include:

Deals that did not meet our S&P screening, but are notable for their scale or intent, include:

Key trends and insights

Sub-sector highlights

Key trends and insights

Sub-sector highlights

See also: Insurance Coverage Porn

Conclusion and outlook

Even though announced deals have been light in the first half of 2017 compared with the second half of 2016, activity should intensify in the remainder of 2017 as insurers focus on cutting costs, achieving scale and enhancing and streamlining or consolidating dated technologies.

See also: Insurance Coverage Porn

Conclusion and outlook

Even though announced deals have been light in the first half of 2017 compared with the second half of 2016, activity should intensify in the remainder of 2017 as insurers focus on cutting costs, achieving scale and enhancing and streamlining or consolidating dated technologies.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

John Marra is a transaction services partner at PwC, dedicated to the insurance industry, with more than 20 years of experience. Marra's focus has included advising both financial and strategic buyers in conjunction with mergers and acquisitions.

Risk management is ever-changing and evolving in K-12 schools. It is vital to stay on top of emerging issues.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Mark Walls is the vice president, client engagement, at Safety National.

He is also the founder of the Work Comp Analysis Group on LinkedIn, which is the largest discussion community dedicated to workers' compensation issues.

In baseball, an at-bat's success is capped at four runs. In business, "every once in a while you... hit the ball so hard you get 1,000 runs.”

“We have a very distinctive approach that we have been honing and refining and thinking about for 22 years. It’s really just a few principles that we use, as we go about thinking through the different activities we work on.”See also: Time to Rethink Silicon Valley? Those few principles are: 1. Customer obsession This is the fundamental driving force behind Amazon’s business. Instead of, say, a competitor obsession, technology obsession or product obsession model. These other models can work just fine. A competitor obsession can be a very good strategy for some companies: You have to watch your competitors very closely. If they latch onto something that’s working, you duplicate it as quickly as possible. It means you don’t have to be a pioneer, and you don’t have to venture down many blind alleys. But there are disadvantages, and the customer obsession model is the one Bezos believes is right for Amazon, in combination with the following two principles. 2. A willingness, or even an eagerness to invent and pioneer This marries very well with the customer obsession. According to Bezos, customers are always dissatisfied, even when they think they are happy. They actually do want a better way; they just don’t know what that way should be yet. Customer obsession is not just listening to your customers, but it means inventing on their behalf. It’s not their job to invent for themselves, you must be the inventor and the pioneer for them. 3. Long-term oriented Bezos encourages his employees not to think in two- to three-year timeframes, but in five- to seven-year timeframes. People often congratulate Bezos on quarterly results, but for Bezos these results were actually baked in about three years ago. Today, he’s thinking about a quarter that’s going to happen in 2020. Next quarter, for all practical purposes, is probably already done and has been done for a couple of years. But the long-term mentality is not a natural way for humans to think. Bezos believes it’s a discipline that you have to train and build for.

“If you start thinking this way, it changes how you spend your time, how you plan, where you put your energy. Your ability to look around corners improves. Many things just get better.”In conclusion, Amazon is an approach and a collection of principles that they embed into how they think and work. Failure and the importance of experimentation Despite being the world's richest person, and Amazon being wildly successful, what keeps Bezos sharp and focused? It’s the fear of Amazon losing its way in one of the key areas mentioned above. Or that they become overly cautious, or failure-adverse, and therefore become unable to invent and pioneer.

“You cannot invent and pioneer if you cannot accept failure. To invent, you need to experiment. If you know in advance that it’s going to work, it is not an experiment.”Failure and invention are inseparable twins. But it’s embarrassing to fail. If you have a 10% chance of a 100x return, you should take that bet every time, but you will still be wrong nine times out of 10, and you’ll feel bad about every one of those nine failures, even embarrassed. Overcoming this fear is vital, particularly in the technology business. In technology, the outcomes can be very long-tailed, with an asymmetric payoff. This is why you need to do so much experimentation. As an illustration:

“In baseball, everybody knows that if you swing for the fences, you hit more home runs, but you also strike out more. But baseball doesn’t go far enough [as an analogy for technology]. No matter how well you connect with the ball, you can only get four runs. The success is capped at those four runs. But in the technology business, every once in a while you step up to the plate, and you hit the ball so hard you get 1,000 runs.”This asymmetric payoff makes it obvious to experiment more, increasing the chances of that 1,000-run hit. It’s important to make this distinction on failure, though: The right kind of failure is when working on an invention, an experiment that you cannot know the outcome of. The wrong kind of failure is when you have some operational history in the task, where you know what you’re doing, but you just screw it up. This is not a good failure. An example from Bezos:

“We’ve opened 130 fulfillment centers now; we’re on the eighth generation of our fulfillment center technology. So if we opened a new center, and just messed it up, that’s not an experiment, that’s bad execution.”Defining your big ideas Any entrepreneur, organization or governmental institution should identify their big ideas that encapsulate what they’re trying to do. There should only be two or three of these big ideas. The main job of a senior leader is to identify those important ideas, and then to enforce great execution on them throughout the organization. The good news is that the big ideas are usually incredibly easy to identify, and in most cases you’ll already know what they are. For Amazon’s consumer business, the three big ideas are:

“How do we always deliver things a little faster? How do we always reduce our cost structure, so that we can have prices that are a little lower?”See also: The Key to Digital Innovation Success The big ideas are stable. They will most probably be the same in 10 years. Customers will still like low prices and faster delivery. No matter what happens with technology, these things will still remain true.

“When you have your big ideas, you can keep putting energy into them. You spin up flywheels around them, and they’ll still be paying you dividends 10 years from now."Bezos also discusses machine learning, renewable energy and space exploration, but not once in the entire discussion does he mention the word "innovation." A reminder that those who really do innovate don't talk about innovation.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Are autonomous vehicles inevitable? Probably. Are they imminent? Probably not, at least on a widescale basis.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

William C. Wilson, Jr., CPCU, ARM, AIM, AAM is the founder of Insurance Commentary.com. He retired in December 2016 from the Independent Insurance Agents & Brokers of America, where he served as associate vice president of education and research.