Harvey Hammers Home NFIP Issue

As National Flood Insurance Program comes up for renewal, it may be time for the federal government to get out of the flood insurance business.

As National Flood Insurance Program comes up for renewal, it may be time for the federal government to get out of the flood insurance business.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Michael Murray is a University of Chicago-trained economist passionate about providing decision-quality information and insight that helps others profit from deep understanding of both the big picture and subtle nuances.

We're all excited by insurtech's prospects -- but it’s easy to feel smart before the test begins. Let's see what Hurricane Harvey shows us.

As Hurricane Harvey finally relents, the insurance industry is about to experience the flip side of a famous line from Warren Buffett. Talking about how investment portfolios shouldn’t be judged in good times, Buffett said, “Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.” Well, with the rain and the rain and the rain that Harvey inflicted on Houston and surrounding areas, we’re going to get to see who in the insurance world can swim. That question will take two forms, one that we’ve seen in every disaster since time immemorial, but the other a new one, about insurtech. The normal one is about whether insurers will perform in their moment of truth, or whether we’ll find the kinds of dubious decisions by adjusters and faked engineering reports that led to improperly denied claims and gave insurance a black eye after Superstorm Sandy. In the case of Harvey, the question for the industry is, essentially: Do insurers want to be Joel Osteen or J.J. Watt? As you may know, given that he’s all over TV, Osteen is the senior pastor at a megachurch in Houston who was mocked on social media for being slow to open the doors of his “prosperity gospel” Christian church and provide shelter and aid for those displaced by the hurricane. He says that he has been maligned and that he was always ready to help, if the city had asked, but his many critics have noted that nobody had to ask Houston’s mosques to open their doors and made Osteen the king of memes this week. Osteen is damaged. The only question is how badly. On the flip side is J.J. Watt, the all-everything defensive lineman for the Houston Texans. Very early in the storm, he made a personal pledge of $100,000 and asked for others to kick in, stating a goal of $200,000. Well, his sincerity and concern went viral, drawing donations from tiny to huge, from Drake to Walmart. Last I checked, total donations exceeded $20 million. With the waters receding, Watt and teammates will be personally going around the city, delivering water, clothing and everything else he’s bought to hand out. He could run for king in Texas, and nobody would get in his way. While acknowledging that insurance is a business that has no obligation to pay more than it owes policyholders, I think the choice is clear: Be like J.J. Watt as much as you can. Don’t be Joel Osteen. See also: Harvey: Tips to Avoid Claim Issues The new question is trickier. The insurtech movement has been around for a few years now, but Hurricane Harvey is the first true catastrophe that has happened during a time when the insurance industry is laying a claim to innovation. (For good measure, Typhoon Hato has been hammering Macau and Hong Kong at the same time.) We’re about to find out how innovative we really are. Some companies are following the traditional playbook and dispatching armies of adjusters to the afflicted region. But we’ll also see the skies filled with drones and will learn how effective they can be at documenting the damage and how much their work still has to be supplemented by humans. We’ll learn a lot about the “gig economy” and whether part-time workers, such as the “Lookers” provided by WeGoLook, can efficiently supplement the full-time insurance workforce, speed the process of claims and slash away at the costs of sorting out a full-on disaster. Supposedly, insurtech is letting everything happen faster. Startups such as ViewSpection and MondCloud provide for self-service on claims, letting individuals send photos and videos and allowing insurers to do triage and pay easy claims quickly. But reality may intrude. Every time I see a photo of some aid facility and spot a sign saying “Free legal services,” I want to applaud those who are helping the injured pro bono, but the cynic in me sees lawyers fishing for clients. I suspect that the hurricane is a full-employment act for every recent law school graduate in Texas. The lawyers, of course, have a vested interest in avoiding quick settlements, so they can work the insurers, take thousands of cases to court and perhaps find some lucrative class actions. Insurtechs, meet lawyers. We’ll have to see how that goes. I don’t often bet against the lawyers. Insurers have begun using chatbots, such as Pypestream’s, in their call centers, which should help handle the deluge of calls that will come in from customers and allow insurers to contact customers more often and more effectively to keep them up to date on the progress of claims. We’ll have to see how insurers do about handling customers' concerns in these hours and days and weeks of need, as well as what role technology plays. Better data and analytics, sometimes powered by AI, are supposedly making us all smarter about mitigating risks, underwriting and everything else, but it’s easy to congratulate yourself on being smart when you don’t face a test. In the real test -- accuracy -- I’d say insurtech startup HazardHub wins early points for putting out an analysis right before the storm saying that $77 billion of property was at risk in Houston, quite a bit higher than other estimates I saw – though lower than some estimates now circulating, and damage estimates always seem to grow, never diminish. We’ll see whether the powerful new analytics let any company in particular get away from the risks in Houston – keeping in mind that ProPublica identified the particular risks in Houston, because of lack of restrictions on real estate development, in a story published last year. If the journalists could spot the risks, how did the insurers do? The verdicts will take weeks and months to come in, because the damage has been so extensive and because problems are still developing in what continues to be a stew of mold, fetid water and chemicals. But we’ll get a sharp sense of where innovation has, in fact, happened and where it needs to go – if we keep our eyes open, evaluate the results honestly and take the lessons seriously. There’s one other question that needs to be answered, too, this one on the government policy level. Flood insurance isn’t working in the U.S., so what do we do about it? Perhaps lulled by a lack of major storms hitting the U.S., homeowners have increasingly declined to purchase policies, so estimates are that 80% to 85% of homes in Houston were not covered. Meanwhile, the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), which provides so much of the coverage, is already heavily in debt because it underprices risk and hasn't recovered from Superstorm Sandy. By law, the NFIP needs to be renewed this month, but we’ve all seen how dysfunctional Congress is these days, and Congress has even more pressing priorities this month, such as dealing with the budget and raising the national debt ceiling. The best proposal I’ve seen so far is to require that homeowners and renters insurance, commercial property policies, auto policies and so on all have a flood piece to them, so that citizens carry the responsibility and so that risk is priced in the market, rather than being dumped on the federal government. See also: Time to Mandate Flood Insurance? One person attached a compelling comment to this article on how the federal government, not insurers (and, ultimately, the insured public) will pay for the recovery from Hurricane Harvey: “Homeowners have three options: 1) buy flood insurance through the NFIP, 2) live in a non-flood plain or 3) accept the risk of living in a flood plain. Option 4 of Harvey victims expecting insurers/taxpayers to compensate them for their increased risk is not an option.” A century ago, in the earliest days of IBM, founding CEO Tom Watson Sr. placed signs in offices that said, “Think.” When the company sparked fears of bankruptcy 25 years ago, wags penciled in two words underneath some of those signs, so they read, “Think – or Thwim.” Flood insurance in the U.S. is in “Think or Thwim” mode. I hope we think.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Paul Carroll is the editor-in-chief of Insurance Thought Leadership.

He is also co-author of A Brief History of a Perfect Future: Inventing the Future We Can Proudly Leave Our Kids by 2050 and Billion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn From the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last 25 Years and the author of a best-seller on IBM, published in 1993.

Carroll spent 17 years at the Wall Street Journal as an editor and reporter; he was nominated twice for the Pulitzer Prize. He later was a finalist for a National Magazine Award.

We should abolish the NFIP and mandate property coverage by all owners and tenants in property, auto and other policies.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

William C. Wilson, Jr., CPCU, ARM, AIM, AAM is the founder of Insurance Commentary.com. He retired in December 2016 from the Independent Insurance Agents & Brokers of America, where he served as associate vice president of education and research.

Insurers must change direction and move from the data-and-analytics-investment “comfortable zone” and over into innovation.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Karen Pauli is a former principal at SMA. She has comprehensive knowledge about how technology can drive improved results, innovation and transformation. She has worked with insurers and technology providers to reimagine processes and procedures to change business outcomes and support evolving business models.

And nobody looks good. Not Express Scripts (the PBM), Kaleo (the drug maker) and certainly not the plans that pay the hefty drug prices.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

David Contorno is president of Lake Norman Benefits. Contorno is a native New Yorker and entered this field at the young age of 14, doing marketing for a major life insurance company.

Disaster mitigation and restoration services are critical, but how you manage these services may affect the outcome of your claim.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Jeff Esper is director of marketing and business development for RWH Myers, where he has developed a dynamic educational marketing program designed to share expert insights with the risk management community via web meeting, live presentation and blog (rwhMyersInsights.com).

Saying no is hard, but even harder is living the life you don't want to lead because you couldn't say no. Saying no just takes practice.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Andy Molinsky is a professor at Brandeis University’s International Business School, with a joint appointment in the Department of Psychology.

He received his Ph.D. in organizational behavior and M.A. in psychology from Harvard University.

Don't view change as black and white. For instance, a digital mix including agent channels outperforms a strictly D2C approach.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Eric Gewirtzman, CEO and co-founder of Bolt Solutions, is a leading force for innovation in the insurance industry, blending more than 20 years of expertise with extensive experience in creating and delivering game-changing insurance-related products and services.

Premium financing options that help clients afford the best policies on the market are a great way to generate customer loyalty.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Sean Jagroop is director of premium financing for Fortegra Financial Corporation (a Tiptree Inc. company).

Distribution channels are exploding, but the industry still has a fundamental problem: We can't even agree on who the customer is.

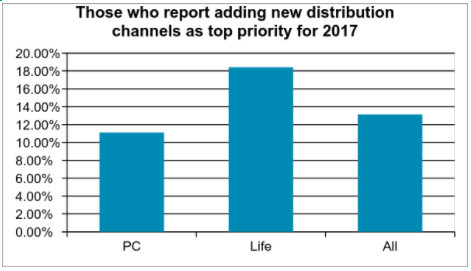

Source: Celent[/caption]

The kinds of strategies carriers take are heavily influenced by their view of the agent. In no other industry that I know of do we have a disagreement about who the customer is. Yet in the insurance industry, this is a matter of religion for many people. Some insurers say that the policyholder is the customer. After all, they’re the ones who write the check and use the service. But others are adamant that the agent is the customer. They influence or make the placement decision — deciding which insurer will write the account.

This question of who is the agent appears to have an impact on the investments insurers are making when it comes to managing the channels. Those who see the agent as their primary customer also are more likely to see distribution channel management as a top corporate priority.

In addition to the traditional channels, a number of new channels are emerging. The biggest news here is the explosion of insurtech startups that have high hopes of disrupting the acquisition process. They provide a unique experience online and hope to garner a large portion of the online marketplace because of their ease of doing business. Some focus on unique slivers of the marketplace. We are aware of more than 145 startups in the US and over 300 worldwide.

While a few insurers are very worried about the impact of InsureTech startups, most are watching closely and a little worried. This is more true for PC insurers where more than 40% say they’re a little worried – likely because of the greater activity in PC. Life insurers generally are watching, but not too worried, or see them as potential partners (31%).

Direct-to-consumer isn’t limited to insurtech startups. There are also a large number of insurers that are actively engaged in building out direct-to-consumer capabilities. Many insurers offer some sort of direct sales capabilities for personal auto. Increasingly, they are extending to this direct sales capability to more complex lines including homeowners, workers compensation, and small business. To be successful here, an insurer has to have a streamlined process, a slick user interface, minimal data input, tailored advice, and real-time decisions.

However, going direct to the consumer can create channel conflict. A variety of techniques are utilized to include and preserve the existing channel. Some will use a different brand such as biBerk, Say Insurance, TypTap, Haven Life, or eSurance. Some will assign an agent using algorithms that take into account location, status, or current production levels. Some will prompt the consumers to choose an agent.

Going direct isn’t the only new distribution strategy carriers are experimenting with. Digital agents, aggregators, partnerships with other carriers and partnerships with non-traditional distributors are all gaining traction. As consumers increasingly expect instant action, insurers are looking for ways to be available at the point of need rather than after the need has been generated.

Many insurers have defined themselves by their channel, saying “We’re a direct writer” or “We’re an independent agency company.” You don’t have to abandon those channels. But as a CEO of an insurtech startup said in a recent conversation, “Choosing your channel as the driving identity of your company is like me wearing a high school letterman jacket when I go out to dinner. It may be part of my identity, but I’m a 42 year old man. It doesn’t work anymore.” For most insurers, shedding the letterman jacket means integrating multiple distribution channels into whatever their historic context is.

See also: How to Find Distribution Payday

This doesn’t come cheap. Expanding channels requires expanded technology capabilities. As consumers become more digital, the channel that is changing the most is the agent channel. Consumers are already voting with their wallet and moving online in droves, and insurtech firms are taking advantage of that. But it’s not easy for insurers to just go direct. Most insurers don’t have the skills necessary to sell a policy. They may have programs to help the agents, but don’t have their own capabilities. Decisions need to be made about how to proceed. Will they create an in-house call center? Will they commit marketing dollars to organically generate traffic to the website?

As these operational decisions are being made, technology capabilities also must be expanded. Those who are going direct require a slick UI on the website as well as business rules, prefill, and workflow on the policy admin side to support straight-through processing. Ongoing servicing requires the ability to expose policies, bills, and claims functionality. Those who are partnering with aggregators or digital agencies need to build out connectivity solutions to pass data back and forth. Those who are partnering with other carriers may need an agency management system to track the leads and the commissions associated with them. And of course, the demand for data to manage these new channels is voracious. Distribution strategies are increasingly driving IT investments.

While multiple channels are effective at targeting specific markets, the increasing complexity of managing these channels is placing pressure on IT organizations. Additionally, the explosion of insurtech startups carries with it the potential for channel disruption. Carriers can work with these startups, invest in the startups, or imitate the startups, but those who ignore them do so at their own peril.

Source: Celent[/caption]

The kinds of strategies carriers take are heavily influenced by their view of the agent. In no other industry that I know of do we have a disagreement about who the customer is. Yet in the insurance industry, this is a matter of religion for many people. Some insurers say that the policyholder is the customer. After all, they’re the ones who write the check and use the service. But others are adamant that the agent is the customer. They influence or make the placement decision — deciding which insurer will write the account.

This question of who is the agent appears to have an impact on the investments insurers are making when it comes to managing the channels. Those who see the agent as their primary customer also are more likely to see distribution channel management as a top corporate priority.

In addition to the traditional channels, a number of new channels are emerging. The biggest news here is the explosion of insurtech startups that have high hopes of disrupting the acquisition process. They provide a unique experience online and hope to garner a large portion of the online marketplace because of their ease of doing business. Some focus on unique slivers of the marketplace. We are aware of more than 145 startups in the US and over 300 worldwide.

While a few insurers are very worried about the impact of InsureTech startups, most are watching closely and a little worried. This is more true for PC insurers where more than 40% say they’re a little worried – likely because of the greater activity in PC. Life insurers generally are watching, but not too worried, or see them as potential partners (31%).

Direct-to-consumer isn’t limited to insurtech startups. There are also a large number of insurers that are actively engaged in building out direct-to-consumer capabilities. Many insurers offer some sort of direct sales capabilities for personal auto. Increasingly, they are extending to this direct sales capability to more complex lines including homeowners, workers compensation, and small business. To be successful here, an insurer has to have a streamlined process, a slick user interface, minimal data input, tailored advice, and real-time decisions.

However, going direct to the consumer can create channel conflict. A variety of techniques are utilized to include and preserve the existing channel. Some will use a different brand such as biBerk, Say Insurance, TypTap, Haven Life, or eSurance. Some will assign an agent using algorithms that take into account location, status, or current production levels. Some will prompt the consumers to choose an agent.

Going direct isn’t the only new distribution strategy carriers are experimenting with. Digital agents, aggregators, partnerships with other carriers and partnerships with non-traditional distributors are all gaining traction. As consumers increasingly expect instant action, insurers are looking for ways to be available at the point of need rather than after the need has been generated.

Many insurers have defined themselves by their channel, saying “We’re a direct writer” or “We’re an independent agency company.” You don’t have to abandon those channels. But as a CEO of an insurtech startup said in a recent conversation, “Choosing your channel as the driving identity of your company is like me wearing a high school letterman jacket when I go out to dinner. It may be part of my identity, but I’m a 42 year old man. It doesn’t work anymore.” For most insurers, shedding the letterman jacket means integrating multiple distribution channels into whatever their historic context is.

See also: How to Find Distribution Payday

This doesn’t come cheap. Expanding channels requires expanded technology capabilities. As consumers become more digital, the channel that is changing the most is the agent channel. Consumers are already voting with their wallet and moving online in droves, and insurtech firms are taking advantage of that. But it’s not easy for insurers to just go direct. Most insurers don’t have the skills necessary to sell a policy. They may have programs to help the agents, but don’t have their own capabilities. Decisions need to be made about how to proceed. Will they create an in-house call center? Will they commit marketing dollars to organically generate traffic to the website?

As these operational decisions are being made, technology capabilities also must be expanded. Those who are going direct require a slick UI on the website as well as business rules, prefill, and workflow on the policy admin side to support straight-through processing. Ongoing servicing requires the ability to expose policies, bills, and claims functionality. Those who are partnering with aggregators or digital agencies need to build out connectivity solutions to pass data back and forth. Those who are partnering with other carriers may need an agency management system to track the leads and the commissions associated with them. And of course, the demand for data to manage these new channels is voracious. Distribution strategies are increasingly driving IT investments.

While multiple channels are effective at targeting specific markets, the increasing complexity of managing these channels is placing pressure on IT organizations. Additionally, the explosion of insurtech startups carries with it the potential for channel disruption. Carriers can work with these startups, invest in the startups, or imitate the startups, but those who ignore them do so at their own peril.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Karlyn Carnahan is the head of the Americas Property Casualty practice for Celent. She focuses on issues related to digital transformation. Carnahan is the lead analyst for questions related to distribution management, underwriting and claims, core systems and operational excellence.