Better Treatments for Opioid Addiction

Will insurers acknowledge the severity of the opioid threat by subsidizing better treatments, like those employed outside the U.S.?

Will insurers acknowledge the severity of the opioid threat by subsidizing better treatments, like those employed outside the U.S.?

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

The dark side of technology—namely ransomware attacks—is now infiltrating self-insured municipalities.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Jim Leftwich has more than 30 years of leadership experience in risk management and insurance. In 2010, he founded CHSI Technologies, which offers SaaS enterprise management software for small insurance operations and government risk pools.

If you have provided insurance services to the art community for long enough, you will receive a “Friday phone call.” Be careful.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Anne Rappa has more than 23 years’ experience in the fine art insurance field in representing large and complex museum, commercial and private and corporate collection risks. She has both specialty fine art insurance as well as a general insurance background.

You know that ugly workers' comp case is probably going to settle. Muster your courage to make it happen sooner.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Teddy Snyder mediates workers' compensation cases throughout California through WCMediator.com. An attorney since 1977, she has concentrated on claim settlement for more than 19 years. Her motto is, "Stop fooling around and just settle the case."

Don’t ask what changes mean for you. Ask instead what these changes mean to the marketplace – to each of us as consumers.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Mike Manes was branded by Jack Burke as a “Cajun Philosopher.” He self-defines as a storyteller – “a guy with some brain tissue and much more scar tissue.” His organizational and life mantra is Carpe Mañana.

Insurers must drive operational efficiency and reduce expenses. Event response and claims automation is a great place to start.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Rick Vissering is a risk management and insurance industry professional with over 35 years of experience. Vissering’s knowledge of the P&C market ranges from claims handling to portfolio management, underwriting, catastrophe models and even systems design and development.

Here are case studies to demonstrate good and bad "postvention"--psychological first aid after a suicide that affects a workplace.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Sally Spencer-Thomas is a clinical psychologist, inspirational international speaker and impact entrepreneur. Dr. Spencer-Thomas was moved to work in suicide prevention after her younger brother, a Denver entrepreneur, died of suicide after a battle with bipolar condition.

The insurance industry has been "Amazoned," as customers increasingly demand the sort of easy interaction that the company provides. But the initial pressure is just a taste of what is to come, as the industry goes through the sort of "disaggregation" that Amazon has forced on the world of retailing. The change will alter the basis for competition for many companies and, thus, the skills that will be needed to thrive.

Just look at Sears, J.C. Penney or any number of other retailers to see the dangers that can arise for incumbents when digital technology breaks an industry down into its basic components and allows the nimblest to reassemble the parts in more efficient or appealing ways. Amazon used technology to separate the testing and buying parts of shopping. Instead of going into a store, finding something you like and buying it there, you can complete the purchase at the best price you find on your smartphone. Amazon also pulled the warehousing function out of stores' back rooms and centralized it. Less capable retailers couldn't withstand the loss of sales and of the warehousing piece of their business model.

There are, of course, opportunities, too. Best Buy's Geek Squad managed to take a service function previously fulfilled by the manufacturers or by separate businesses and incorporate that capability into store/showrooms. Allstate, through its purchase of SquareTrade, is stripping warranty business away from manufacturers and retailers. Tesla's use of centralized showrooms is duplicating Amazon's move on warehousing and could take away a major function of car dealerships, while eliminating the cost of financing billions of dollars of cars sitting on lots.

In insurance, you can see the disaggregation coming based on where the innovators are placing their bets—McKinsey reports that, despite early expectations of some sort of killer app, only about 10% of insurtechs are trying to disrupt the industry business model, while two-thirds are working to perfect some piece of the value chain.

Snapsheet tackles the claims process. Pypestream provides customer engagement. Carpe Data and Groundspeed go after big issues in data and analytics. Platforms like Bolt let customers pick and choose products from an array of insurers, so they can search for the best of breed in each line and not be limited once they choose a principal insurer. RiskGenius makes it easy to take the policy review process for customers and their agents down to comparisons of individual clauses, so they can find the best coverage and build the policies they want.

As this specialization continues, the generalists will have trouble keeping up. Sure, the biggest incumbents will have the resources to compete, at least for a while, but how many companies will be able to match, say, the claims process designed by an insurtech with tens of millions of dollars of backing and access to the kind of programming talent that gravitates to software startups?

Increasingly, the build vs. buy decision will go away and be replaced by a need to partner with insurtechs that have optimized parts of the insurance process. The switch to partnerships may force major changes to IT systems, so they can work with others' software and not function just as a closed system, based only on what's done in-house. The change will also require a workforce able to get past the not-invented-here bias at many incumbents and to collaborate with partners.

Leadership will be required. What CIO got promoted by saying, "Nope, I don't think my people can build what you want, at least not as well as that insurtech"? The CEO will likely need to intervene to make sure decisions are made based on fact, not emotion.

The good news is that, once a company adapts to disaggregation, it can reassemble the pieces of the industry in new and creative ways. Look at Best Buy, which some had on a death watch because of the "showrooming" phenomenon but has reinvented itself in the new world of retailing. Or look at Amazon itself: It began by just selling books but honed its business model and is now eating every market in sight.

Cheers,

Paul Carroll

Editor-in-Chief

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Paul Carroll is the editor-in-chief of Insurance Thought Leadership.

He is also co-author of A Brief History of a Perfect Future: Inventing the Future We Can Proudly Leave Our Kids by 2050 and Billion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn From the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last 25 Years and the author of a best-seller on IBM, published in 1993.

Carroll spent 17 years at the Wall Street Journal as an editor and reporter; he was nominated twice for the Pulitzer Prize. He later was a finalist for a National Magazine Award.

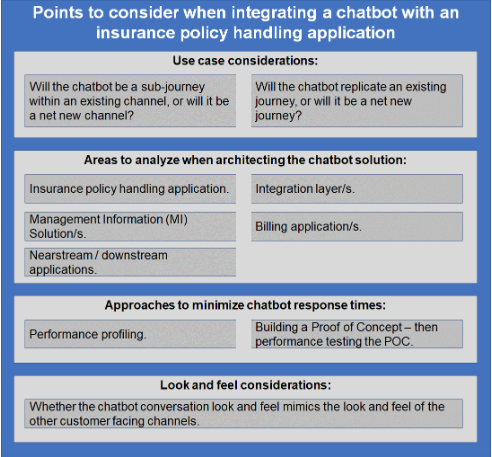

Here are key insights on how to best use chatbots in the quote-and-buy process for customers.

See also: Chatbots and the Future of Interaction

Key Takeaways:

See also: Chatbots and the Future of Interaction

Key Takeaways:

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Renaud Million is the CEO of Spixii, a leading conversational automation platform for insurance customer-facing processes.

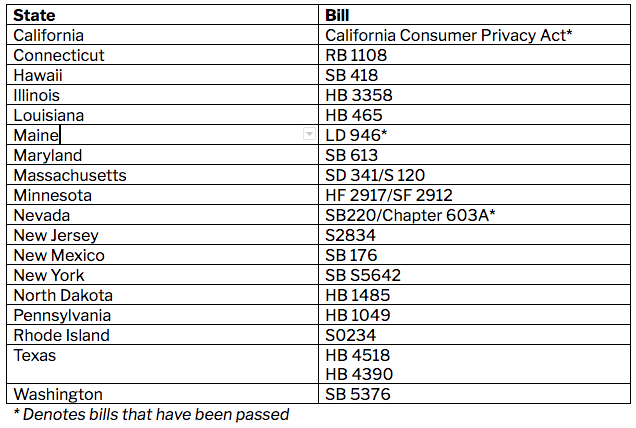

The California Consumer Privacy Act amps up the need for cyberinsurance -- and for "tokenization."

Although organizations are exempt from the California law when “assembling or collecting information about natural persons for the primary purpose of providing the information to an insurance institution or agent for insurance transactions”—thanks to Assembly Bill 981, which was passed in May—organizations are still subject to its requirements when the scope and use of personal data exceeds those specific operations. In many cases, the compliance concerns of insurance companies will be solely with that of their policyholders, so it is in the best interest of both parties to ensure steadfast organizational compliance with an emphasis on reducing risk and anticipating future regulations.

See also: Blockchain, Privacy and Regulation

Of particular importance to these insurers and their insureds is the controversial concept of private right of action, which allows individuals whose privacy has been violated to bring civil suits against noncompliant parties. Originally, this portion of the California law could have exponentially increased the financial consequences of a breach by subjecting violators to class-action claims of damages from victims, on top of the compliance-related fines levied by the state. It has since been limited to injunctive or declaratory relief, but other developing statutes include language similar to the original bill’s treatment of private right of action. Louisiana, Massachusetts, New York, North Dakota and Rhode Island all are working on bills that include a private right of action, with New York’s being especially expansive and potentially heavy-handed toward violators. In addition to including a private right of action, New York’s proposal has no minimum gross revenue requirement, meaning all companies—regardless of size—will be subject to the law’s rules and penalties. This has led critics to question the feasibility of fairly enforcing what they deem to be overly broad regulations aimed at punishing well-meaning organizations that cannot keep up with the evolving privacy space.

In terms of its impact on the insurance industry, the resulting legislative inconsistency will hit the big names the hardest, but it still does no favors for mid-size carriers struggling to keep up with their state or regional laws. In addition to meeting their own compliance obligations, they will have to accurately gauge the risk and potential penalties presented by the difficulty policyholders will have satisfying theirs. Insurers might not have to walk through the minefield, but they will have to clean up the mess inside it once something goes wrong.

As we discussed in a previous post, the difficulty insurance companies already experience when attempting to create reliable cyberinsurance policies is inhibiting the industry’s ability to provide much-needed coverage. The private right of action and other uncertain aspects of these laws further complicate the task of accurately estimating and pricing the cost of cyberinsurance coverage by expanding the potential recompense for breach victims. When coupled with the fact that no federal privacy law exists—allowing each state to establish its own set of rules for what constitutes personal data and how it should be protected—offering cyberinsurance can seem like an almost untenable prospect. However, a risk-reducing, compliance-enabling solution exists in the marketplace: tokenization.

See also: Mobile Apps and the State of Privacy

Tokenization, such as that offered by the TokenEx Cloud Security Platform, especially excels at reducing risk through its use of pseudonymization and secure data vaults. Pseudonymization, also known as deidentification, is the process of desensitizing data to render it untraceable to its original data subject. It does so by replacing identifying elements of the data with a nonsensitive equivalent, or token, and storing the original data in a cloud-based data vault. This virtually eliminates the risk of theft in the event of a data breach, and, as a result, tokenization is recognized as an appropriate technical mechanism for protecting sensitive data in compliance with the CCPA and other regulatory compliance obligations. Because tokenization satisfies controls concerning the processing of sensitive data, it can prevent losses stemming from fines and other penalties as a result of noncompliance.

As new laws emerge and the privacy landscape in the U.S. continues to shift, it is crucial for both insurance companies and their policyholders to prioritize risk minimization. And tokenization is an essential tool for significantly reducing the likelihood of a cyber event, and as a result, a claim.

Although organizations are exempt from the California law when “assembling or collecting information about natural persons for the primary purpose of providing the information to an insurance institution or agent for insurance transactions”—thanks to Assembly Bill 981, which was passed in May—organizations are still subject to its requirements when the scope and use of personal data exceeds those specific operations. In many cases, the compliance concerns of insurance companies will be solely with that of their policyholders, so it is in the best interest of both parties to ensure steadfast organizational compliance with an emphasis on reducing risk and anticipating future regulations.

See also: Blockchain, Privacy and Regulation

Of particular importance to these insurers and their insureds is the controversial concept of private right of action, which allows individuals whose privacy has been violated to bring civil suits against noncompliant parties. Originally, this portion of the California law could have exponentially increased the financial consequences of a breach by subjecting violators to class-action claims of damages from victims, on top of the compliance-related fines levied by the state. It has since been limited to injunctive or declaratory relief, but other developing statutes include language similar to the original bill’s treatment of private right of action. Louisiana, Massachusetts, New York, North Dakota and Rhode Island all are working on bills that include a private right of action, with New York’s being especially expansive and potentially heavy-handed toward violators. In addition to including a private right of action, New York’s proposal has no minimum gross revenue requirement, meaning all companies—regardless of size—will be subject to the law’s rules and penalties. This has led critics to question the feasibility of fairly enforcing what they deem to be overly broad regulations aimed at punishing well-meaning organizations that cannot keep up with the evolving privacy space.

In terms of its impact on the insurance industry, the resulting legislative inconsistency will hit the big names the hardest, but it still does no favors for mid-size carriers struggling to keep up with their state or regional laws. In addition to meeting their own compliance obligations, they will have to accurately gauge the risk and potential penalties presented by the difficulty policyholders will have satisfying theirs. Insurers might not have to walk through the minefield, but they will have to clean up the mess inside it once something goes wrong.

As we discussed in a previous post, the difficulty insurance companies already experience when attempting to create reliable cyberinsurance policies is inhibiting the industry’s ability to provide much-needed coverage. The private right of action and other uncertain aspects of these laws further complicate the task of accurately estimating and pricing the cost of cyberinsurance coverage by expanding the potential recompense for breach victims. When coupled with the fact that no federal privacy law exists—allowing each state to establish its own set of rules for what constitutes personal data and how it should be protected—offering cyberinsurance can seem like an almost untenable prospect. However, a risk-reducing, compliance-enabling solution exists in the marketplace: tokenization.

See also: Mobile Apps and the State of Privacy

Tokenization, such as that offered by the TokenEx Cloud Security Platform, especially excels at reducing risk through its use of pseudonymization and secure data vaults. Pseudonymization, also known as deidentification, is the process of desensitizing data to render it untraceable to its original data subject. It does so by replacing identifying elements of the data with a nonsensitive equivalent, or token, and storing the original data in a cloud-based data vault. This virtually eliminates the risk of theft in the event of a data breach, and, as a result, tokenization is recognized as an appropriate technical mechanism for protecting sensitive data in compliance with the CCPA and other regulatory compliance obligations. Because tokenization satisfies controls concerning the processing of sensitive data, it can prevent losses stemming from fines and other penalties as a result of noncompliance.

As new laws emerge and the privacy landscape in the U.S. continues to shift, it is crucial for both insurance companies and their policyholders to prioritize risk minimization. And tokenization is an essential tool for significantly reducing the likelihood of a cyber event, and as a result, a claim.

Get Involved

Our authors are what set Insurance Thought Leadership apart.

|

Partner with us

We’d love to talk to you about how we can improve your marketing ROI.

|

Robin Roberson is the managing director of North America for Claim Central, a pioneer in claims fulfillment technology with an open two-sided ecosystem. As previous CEO and co-founder of WeGoLook, she grew the business to over 45,000 global independent contractors.

Alex Pezold is co-founder of TokenEx, whose mission is to provide organizations with the most secure, nonintrusive, flexible data-security solution on the market.