I’ve seen many insurance trade press articles or social media posts asking why insurers aren’t using either an Amazon or Netflix business model. The articles or posts mention that Amazon and Netflix are massively successful, are driven by a strong customer focus, have operations throughout the globe and, equally importantly, conduct commerce using web-based mobile apps.

So, should insurers use an Amazon or Netflix business model?

No.

I'll explain why, and also cover the functional areas within the insurance value web that can be strengthened using aspects of or principles driving the Amazon and Netflix business models, but let's start at a very high level. Let's look at: business models, the Amazon business model, the Netflix business model and the insurance industry business model.

I always keep in mind that the insurance industry is not homogeneous. However, for the purpose of this post, I will illustrate an insurance business model that has applicability – at a high level – to all of the non-health-insurance lines of business. Please excuse my broad brushstrokes of the insurance business model that I visualize.

Business Models

The following is from a post I wrote titled: Business Models, Moats, & Start-ups: An Insurance Analyst Perspective.

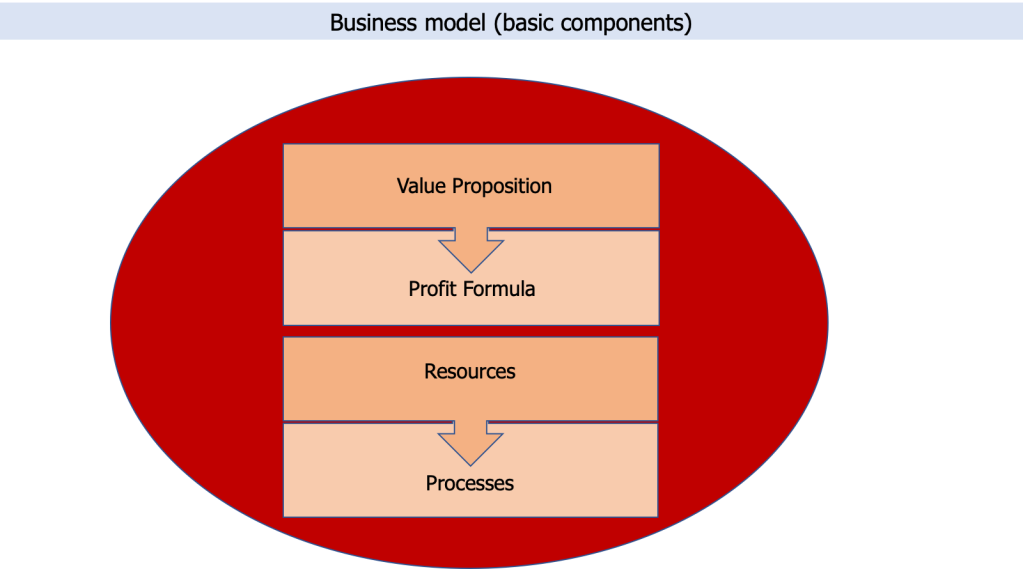

There are many descriptions of business models available from a multitude of sources. I’ve created an illustration from an interview that Harvard Business Publishing had in late 2008 with Professor Clayton Christensen discussing “reinventing your business model.”

To paraphrase Professor Christensen’s description:

First, a firm creates a value proposition. The value proposition is defined in a manner to help someone accomplish a "job" (i.e., fulfill a need) affordably, conveniently and effectively. Next, the firm establishes a formula to deliver the value proposition in a profitable manner. Then, the firm identifies the resources it needs (i.e., buildings, equipment, people, products and technology) to support the value proposition (and deliver it profitably). Finally, processes coalesce that are required to support the firm’s value proposition and resources simply and affordably.

Expanded Business Model

For me, this is a reasonable, logical description of a business model before factoring in the forces within a specific industry that will alter the components to align with them.

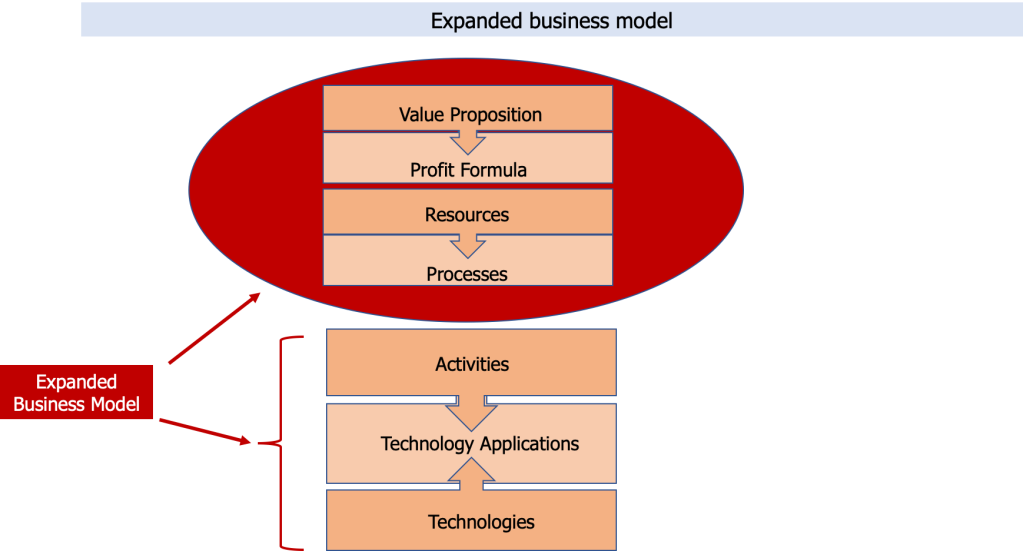

However, I want to expand on Professor Christensen’s business model components. My expansion (see visual below) encompasses three other major components: activities, technology applications and technologies.

These three additional components resemble Russian nesting dolls in that processes are composed of several activities. Each activity can be – and usually is – supported by several technology applications, and, in turn, each technology application can be – and usually is – supported by several technologies.

I think of my three additions to Professor Christensen’s description of a business model as an "expanded business model."

Firms regardless of industry, whether startups or incumbents, need to consider how the set of additional components enable the company to profitably deliver the value proposition (i.e., help a customer fulfill a need) affordably and simply to the company’s target markets -- again, “with regard to the realities of the industry in question.”

For this post, I will not use all of the aspects of the expanded business model to discuss the Amazon, Netflix and insurance industry business models. However, to maintain your sanity and mine, I will discuss the same three elements of the expanded business model (value proposition, profit formula and technology applications) throughout this post.

(I believe that a more extensive discussion encompassing all the components of the expanded model would make sense to write at some point. I’m not sure when I would get to do that.)

Amazon: Industry, Markets and Business Model

In the 2017 letter to shareholders, Jeff Bezos wrote: “One thing I love about customers is that they are divinely discontent. Their expectations are never static: They go up. We didn’t ascend from our hunter-gatherer days by being satisfied. People have a voracious appetite for a better way. And yesterday’s ‘wow’ quickly becomes today’s ‘ordinary.'”

I submit that his company strives to continually provide contentment for his clients in both the consumer and corporate markets that Amazon targets. Whether he succeeds with every initiative, Bezos – based on recorded interviews with him, his letters to shareholders and the stream of new capabilities offered to clients – is driven to continually satisfy people’s voracious appetite by finding a better way for clients to conduct commerce with Amazon.

Amazon Industry and Markets

Industry Description – NAICS

The U.S. government has categorized Amazon as belonging to:

- NAICS code 518210: data processing, hosting and related services

- NAICS code 454110: electronic shopping and mail-order houses.

Note that on a NAICS two-digit level, code 51 encompasses “information” industries, and code 45 encompasses “retail trade” industries.

During my desk research for this post, at first glance it seems that Amazon employs its products, solutions and services from both industries. However, it is more applicable to state that Amazon learns from and leverages its capabilities in each of its NAICS-coded set of industries to satisfy its clients' “voracious appetites” in both of its target markets.

Target Markets

The company began its operations in the consumer markets (selling hard-copy books) in 1994, and in 2004 the firm decided to offer AWS’ Simple Queue Service (and in-depth knowledge of maintaining, enhancing and managing that infrastructure) to clients in corporate markets. A Wikipedia entry about AWS states that: “Amazon Web Services was officially re-launched on March 14, 2006, combining the three initial service offerings of Amazon S3 cloud storage, SQS and EC2.”

Again from Wikipedia: “In 2020, AWS comprised more than 212 services spanning a wide range including computing, storage, networking, database, analytics, application services, deployment, management, mobile, developer tools and tools for the Internet of Things.”

Four principles guide consumer and corporate markets

Bezos stated in the firm’s 10-K for the fiscal year ended Dec. 31, 2019, that the company seeks “to be Earth’s most customer-centric company.” He wrote that the firm is guided by four principles:

- customer obsession rather than competitor focus

- passion for invention

- commitment to operational excellence

- long-term thinking.

At the 2012 re:invent Day 2 conference, Bezos said that the firm’s obsession with retail customers was the same as with corporate AWS customers. He said it was necessary to continually:

- improve the reliability of AWS

- lower prices for AWS clients

- innovate faster APIs for AWS clients.

Constantly lowering costs for customers is part and parcel of the firm’s customer obsession. One major theme that weaves through interviews with Bezos and articles about Amazon is the firm’s drive to answer the question: “How can we generate more revenue from our own infrastructure to lower costs for our (consumer and corporate) customers?”

Summing up Amazon’s consumer market

I think of Amazon as a firm that offers a fusion of physical and digital artifacts, specifically:

- purchased physical and digital artifacts, supported by

- a supply chain (encompassing digital and physical artifacts supported by servers, distribution centers and delivery vehicles), which are in turn supported by

- Amazon’s technology solutions (including AI applications used to quicken and improve customers’ navigation, search and selection of known and predicted consumer product goods (CPG) and media and entertainment products that they might want to consider for future purchase.

I assume that a description of Amazon’s corporate markets, beyond stating that AWS offers scale-as-a-service, could be crafted in a manner that is similar (and more than likely much tighter) to my summary about Amazon’s consumer markets.

However, whether thinking of Amazon’s offerings to its consumer markets or corporate markets, I consider Amazon.com to be an optimization engine that is continually refined to provide retail and corporate customers with an excellent experience conducting commerce with the firm.

Now, let’s discuss the three selected components of the expanded business model (value proposition, profit formula and technology applications).

Value Proposition

I believe that Amazon has two value propositions: one for consumer markets and one for corporate markets. Both are based on the same foundation of customer obsessiveness.

Value proposition for consumer markets: Provide consumers a panoply of digital and physical distribution channels to purchase products from a growing selection of retail and information goods and services at low prices and deliver quickly.

Value proposition for corporate markets: Provide corporations a secure, scalable cloud services platform offering storage, compute, analytics and other capabilities-as-a-service at low prices.

See also: 7 Business Models of the Future for Insurers

Profit Formula

Amazon generates revenue from a wide and expanding selection of sources, including:

- retail (CPG)

- media and entertainment (including Amazon Prime, a subscription service for consumers)

- corporate markets (AWS)

- digital advertising services.

Some of the relatively newer sources of revenue include Amazon’s entry into prescription drugs and groceries (Whole Foods).

Amazon continually strives to find ways to make it easy for its retail consumers to conduct commerce with the firm, not only using mobile apps and the firm’s web site, but also using its voice-responsive Alexa devices and, more lately, shopping at the Amazon Go stores. Amazon is offering its Amazon Go store functionality to other retailers.

Amazon’s net income in 2019 was $11.59 billion, which was up from $10.07 billion in 2018.

Amazon Flywheels: Consumer and Corporate Markets

The firm accomplishes its mission through its stellar implementation of the flywheel, which Jim Collins described in his 2001 book, “Good to Great.” The flywheel strengthens the retail and corporate client experience while simultaneously lowering the firm’s expenses.

One of the best discussions of the Amazon flywheel is given by Simon Torrance (dated April 9, 2018, on YouTube and titled: "New Growth Playbook – Amazon’s Growth Flywheel"). I am using his visual below (with his permission) with some minor alterations.

Amazon continually expands the selection of goods and services for customers to choose (which is why it is number 1 in the visual: It drives the flywheel). Doing that increases traffic to Amazon.com. That traffic both drives expanding selection of goods and services and lowers Amazon’s cost structure, which leads to lower prices. And around the flywheel goes.

But wait a second: Amazon allowed third parties to use Amazon’s infrastructure to offer their own goods and services. Doing this accelerates the speed of the flywheel: increased selection leading to even stronger customer experience and …

Amazon’s implementation of the flywheel also illustrates the firm’s realization that it could leverage knowledge of its own infrastructure by offering that infrastructure (i.e., AWS) to corporations for their use to serve their own clients. Moreover, the visual captures how Amazon bridged the consumer and corporate markets to help their corporate clients, their consumer customers, their Amazon Marketplace participants, IoT developers (in this instance) and, of course, Amazon itself. By introducing its own branded connected IoT physical devices (Alexa, Fire TV Stick), Amazon introduced and accelerated purchases (and the corporate flywheel) that corporations could create and deliver to Amazon’s customers, which strengthens, yet again, Amazon’s experience for consumers.

Technology Applications

(I distinguish between technology and technology applications. For me, AI is a collection of technologies and is not itself a technology application. In this section, I discuss a small selection of technology applications that Amazon uses to strengthen customer experience.)

Amazon constantly strives: to make it easier for consumers to conduct commerce with the firm, to drive down the firm’s costs and to expand the number of retail (CPG) and media and entertainment goods and services that customers might want to purchase. Add all of that to one of the firm’s four principles – its passion for invention – and it is no surprise that Amazon is essentially a CX-driven laboratory that continues to create applications from current and emerging technologies to support the firm’s objectives.

Amazon’s technology applications include:

- Recommendation engines to suggest products that consumers might want to consider purchasing. The recommendation engines are a quick solution to a customer’s need to navigate Amazon’s vast selection and choose a purchase.

- Warehouse robots working with humans to quicken the responsibilities of pickers, packagers and stowers.

- Alexa, the cloud-based, voice-controlled virtual assistant that provides information and, of course, an easy way to purchase goods and services.

- Amazon mobile apps available on iOS, Android and Windows devices.

- eReader (e.g., Kindle – offered as a physical device and as an app available on mobile devices) that enables customers to read purchased books (and magazines) and to purchase more books.

- Amazon Prime Video – a streaming app for movies (licensed and original Amazon content) and television shows available on mobile devices.

Amazon continually leverages what the firm learns using its own capabilities and then refines its operations involving either consumer markets or corporate markets.

AWS and Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) are two examples of Amazon’s expanding its capabilities and profit footprint. A third example is Amazon’s Ground Station-as-a-Service. This is an offering to satellite/Earth observation/NewSpace operators firms that don’t want to build their own ground stations, want to expand the number and location of ground stations they already have built or want to expand the number and location of ground stations they are getting from their current partners.

Netflix: Industry, Markets and Business Model

Industry Description – NAICS

The U.S. government has categorized Netflix as belonging to NAICS code 515210: cable and other subscription programming and NAICS code 532230: video tape and disc rental:

- NAICS 515210 includes: establishments primarily engaged in operating studios and facilities for the broadcasting of programs on a subscription or fee basis.

- NAICS 532230 includes: establishments primarily engaged in renting prerecorded video tapes and discs for home electronic equipment.

When Netflix began operations in 1997 by offering DVD rental by mail, the appropriate NAICS code would have been 532230. Netflix’ shift from renting DVDs by mail to becoming a subscription-based media firm obscures the reality of constant reinvention that is the firm’s hallmark to support its vision of offering a high-quality customer entertainment experience.

Target Markets

Netflix targets the global consumer market with its offerings of on-demand, subscription-based streaming content.

Netflix has become (according to the firm’s 10-K for 2019) “the world’s leading subscription streaming entertainment service with over 167 million paid streaming memberships in over 190 countries enjoying TV series, documentaries and feature films across a wide variety of genres and languages.” Netflix also has approximately two million customers who still rent and return DVDs by mail.

Netflix creates content in different countries around the world and distributes that content worldwide. Below, the chart shows the average paying memberships growing in the four major regions Netflix operates: U.S. and Canada, EMEA, LATAM and APAC. (Note: APAC excludes China and North Korea.)

Creating compelling content

Founder Reed Hastings says, “Our North Star is how do we do the absolute best content we can to please our customers.” Netflix is all about offering compelling stories to become a destination site for customers’ viewing.

Compelling story-telling is an integral component of who we are as humans (see visual). Our distant ancestors drew pictures on walls letting others know where food was located. At almost the end of the 19th century, Thomas Edison built the first movie studio called The Black Maria. Silent movies ruled the era, including Charlie Chaplin’s “Modern Times.” Much more recently, Netflix created the first Netflix Original web television series, which won seven Primetime Emmy awards, two Golden Globe awards, two Screen Actors Guild award and one Satellite award. Through six seasons, House of Cards won 27 awards.

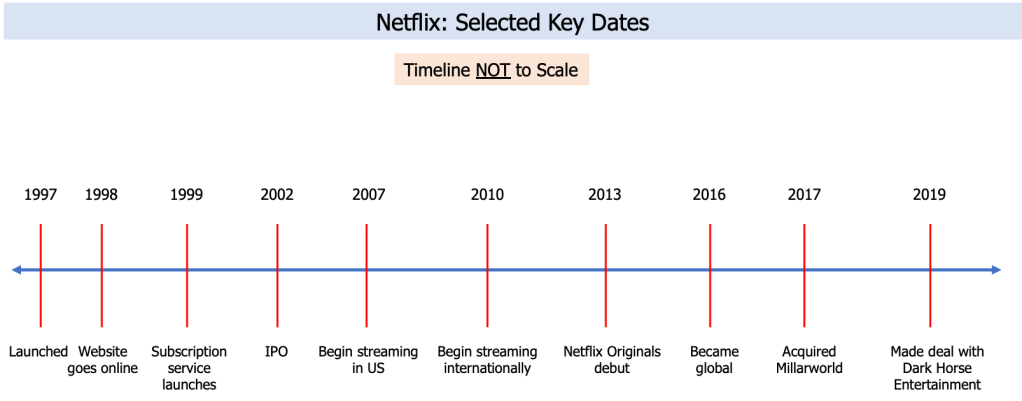

Selected Key Dates in Netflix’ History

Obviously, the dates of incorporation and IPO are very important for Netflix (see visual). However, if I had to pick some other major dates on the Netflix timeline, my choices would be the dates:

- Netflix began streaming (because this initiative redefined the consumer entertainment marketplace to an on-demand (or binging) marketplace)

- of all the acquisitions and partnerships, of which I show only two in the visual. The acquisitions and partnerships provide Netflix with intellectual property (IP) that the firm can use to create series and movies.

Value Proposition

To attract customers from other activities that take place in what Hastings called the consumer’s "moments of truth," Netflix created a value proposition to provide on-demand, personalized, streaming entertainment available for viewing on any internet-connected screen for an affordable, no-commitment monthly fee. Did you catch the "no-commitment monthly fee?" Customers can cancel at any time (and come back when they want).

One of Hastings' guiding principles that drives his company to strengthen and reinvent Netflix is that “time is the real competition.” Not Disney+, not Amazon Prime Video, not Apple TV Plus, not Hulu and not other visual entertainment content but time itself. Time that customers could enjoy by reading a book, taking a walk, going to Starbucks or doing anything in their free time other than watching entertainment on Netflix.

Netflix bolsters the value proposition by allowing members to watch as much as they want, any time, anywhere, on any internet-connected screen. Members can play, pause and resume watching, all without commercials.

Moreover, Netflix puts the member (or customer) center stage by creating metrics based primarily on each customer rather than on the content. From the Product Habits blog: “Cable TV channels typically calculate their audiences based on viewership or how many viewers a TV show has. Netflix comes at this from the opposite direction by focusing on how many movies (or shows) a viewer has watched. Rather than optimizing individual shows to maximize the number of viewers, Netflix instead leverages its vast media catalog to optimize for movies watched per individual user.“

Strength of vision

Netflix intends to stay true to its value proposition by stating (and often restating in articles and interviews) that it has no intention of introducing advertisements into content, adding sports or going into gaming.

Story-telling – whether series, films or unscripted content – makes up the entertainment that Netflix currently offers and plans to offer.

See also: Building a Virtual Insurer Post-COVID

Constant reinvention of Netflix

But that laser focus on story-telling – and not on other content – does not mean that Netflix has not reinvented and will not reinvent itself. Far from it. Reinvention has been the foundation of Netflix’ success for more than two decades.

The firm has moved from DVD rentals by mail to streaming licensed content (and by introducing streaming – or bingeing – the firm redefined what it meant to watch content on the web) to creating and streaming original content.

Refining the amount of content available on Netflix

The phrase used to be, "What’s on [television] tonight?” Since Netflix and other multichannel video programming distributors (MVPD) redefined the "what" (and the "where" and "when") of content to view, people want to know the availability of streaming content.

From an article on Vox dated Jan. 27, 2020, titled “How Netflix is winning more with less content” written by Rani Molla (@ranimolla): “Ten years ago, Netflix had a total of 7,285 TV and movie titles in the U.S., according to streaming service search engine Reelgood. Now it has 5,838. That’s down nearly 50 percent from a peak of about 11,000 titles in 2012, according to Reelgood’s database, but up from 2018, when it had a low of 5,158.

The decline is part of a long-anticipated move by Netflix away from relying on other studios’ content and toward making its own. Netflix is making that transition as other content makers — namely Apple, Disney, NBC and WarnerMedia — launch and grow their own streaming services. This influx of new services also coincides with Netflix paying higher and higher prices to license content, especially if the content belongs to one of its new streaming competitors. Netflix could also be intentionally winnowing its selection as its vast troves of viewer data show it what people actually watch and what it can afford not to license.

Still, Netflix now spends more than half its cash on originals, Chief Financial Officer Spencer Adam Neumann said on the latest earnings call. That’s up from nothing, less than a decade ago. “The future of our business is mostly originals,” Neumann said.

Implications of Netflix creating original content

Netflix is not only talking the talk but walking the talk” about original content. An article dated Jan. 16, 2020, titled, “Netflix Projected to Spend More Than $17 Billion on Content in 2020,” by Todd Spangler, discusses a BMO Capital Markets forecast: “The streamer will invest around $17.3 billion this year in content on a cash basis … up from around $15.3 billion in 2019. Netflix is not expected to ease up any time soon: Its content spending will top $26 billion by 2028, per BMO’s report.”

The spending on original content will have implications on Netflix’ financials. Moreover, creating and distributing original content has many other implications, including:

- decreased licensing cost of other studios' content

- increased costs (for original content)

- increased need, and cost, for people skilled in creating high-quality, desirable content

- tactical hope that original content keeps existing customers and attracts new customers

- significantly more control of how long the (original) content can remain on the Netflix media system for viewing by customers.

Profit Formula

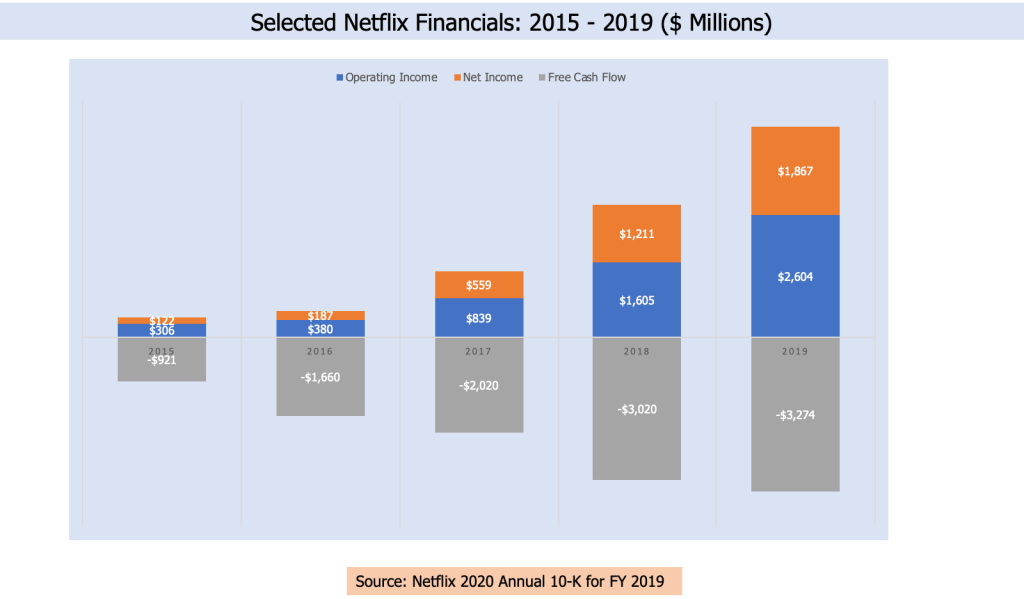

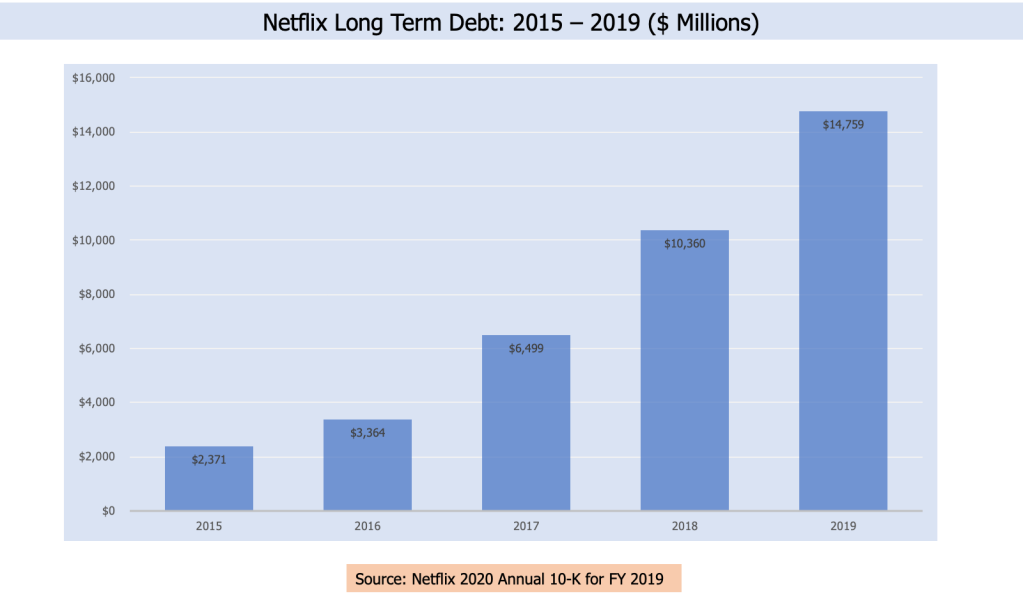

Netflix’ operating income and net income have been steadily increasing from 2015 through 2019. However, Netflix’ free cash flow has steadily declined from -$921 million in 2015 to -$3.3 million in 2019.

Netflix has also seen a steady increase in long-term debt from $2.4 million in 2015 to $14.8 million in 2019.

I think these financials point to the sustainability of the firm: using long-term debt to create a repository of more original content. How many years can Netflix operate in this manner? Keep in mind that I realize that I may very well be wrong on this matter, as I am not a financial analyst — please let me know.

Technology Applications

Netflix strives to keep its members entertained by offering personalized content. Netflix may no longer have the 11,000 titles for viewing it had some years ago, but 5,800-plus titles remains a large content repository. Moreover, the repository is not static: Netflix continues to license content and will continue to create Netflix Originals.

The volume of current and future planned content creates a challenge for Netflix: determining how to steer the appropriate content to each member. Put another way, the continual challenge for Netflix is how to identify and tell each member about the specific content the member would enjoy that is residing in a particular place (at any point in time).

The answer rests with Netflix’ applications of machine learning to improve each member’s experience. Netflix uses machine learning (which is a technology and not a technology application) to optimize the Netflix service end-to-end, including to (this is directly from the Netflix Research web site):

- create and improve the firm’s recommendation engine

- optimize the production of original movies and TV shows

- optimize video and audio encoding

- optimize the in-house Content Delivery Network

- power the firm’s advertising spending

- power the firm’s channel mix

- power the firm’s advertising.

Insurance: Industry, Markets and Business Model

Industry Description – NAICS

The insurance industry has many sub-industries, including the following (using information from the U.S. Census Bureau about the 2017 NAICS codes):

- NAICS code 524113 – Direct life insurance carriers: includes establishments primarily engaged in initially underwriting (i.e., assuming the risk and assigning premiums) annuities and life insurance policies, disability income policies and accidental death and dismemberment insurance policies.

- NAICS code 524126 – Direct property and casualty insurance carriers: includes establishments primarily engaged in initially underwriting insurance policies that protect policyholders against losses that may occur as a result of property damage or liability. Illustrative examples include automobile insurance carriers, direct; malpractice insurance carriers, direct; fidelity insurance carriers, direct; mortgage guaranty insurance carriers, direct; homeowners’ insurance carriers, direct; surety insurance carriers, direct; liability insurance carriers, direct.

- NAICS code 524130 – Reinsurance carriers: includes establishments primarily engaged in assuming all or part of the risk associated with existing insurance policies originally underwritten by other insurance carriers.

- NAICS code 524210 – Agencies and brokerages: includes establishments primarily engaged in acting as agents (i.e., brokers) in selling annuities and insurance policies.

- NAICS code 524291 – Claims adjusting: includes establishments primarily engaged in investigating, appraising and settling insurance claims.

- NAICS code 524292 – Third party administration of insurance and pension funds: includes establishments primarily engaged in proving third party administration services of insurance and pension funds, such as claims processing and other administrative services to insurance claims, employee benefit plans and self-insurance funds.

- NAICS code 524298 – All other insurance-related activities: includes establishments primarily engaged in providing insurance services on a contract or fee basis (except insurance agencies and brokerages, claims adjusting and third party administration). Insurance advisory services, insurance actuarial services and insurance rate-making services are included in this industry.

- NAICS code 525110 – Pension funds: includes legal entities (i.e., funds, plans and programs) organized to provide retirement income benefits exclusively for the sponsor’s employees or members.

- NAICS code 525190 – Other insurance funds: includes legal entities (i.e., funds (except pension, and health – and welfare-related employee benefit funds)) organized to provide insurance exclusively for the sponsor, firm or its employees or members. Self-insurance funds (except employee benefit funds) and workers’ compensation insurance funds are included in this industry.

Keep in mind that not every sub-industry participates in getting and keeping each insurance customer. The role of each sub-industry participant heavily depends on which insurance lines of business the potential client wants (needs?) to purchase, the financial and staff resources of the insurance carriers underwriting the risks and the sub-industry participants involved with customer and claim services.

Two iron-clad rules of insurance commerce

There are two facts that absolutely rule insurance commerce:

- Insurance can only be underwritten in any one or more jurisdictions by an entity regulated and licensed to conduct insurance commerce there.

- Insurance can only be sold by a regulated salesperson who is trained, certified and licensed to sell specific insurance line(s) of business in specific jurisdictions.

Insurers that use algorithms to sell the insurance policy within seconds (or nanoseconds) must ensure that the algorithms comply with the regulatory requirements of carriers and agents to underwrite and sell the policy in the jurisdiction of the sale.

The importance of insurance regulation

Regulation is critically important to underwriting, sale and service. Why the emphasis? Because insurance mitigates or manages the risks to:

- people’s lives, property, income/assets, health, actions and behaviors

- companies' (or non-profits') financial well-being, behaviors, actions, property, products and services.

Target Markets

The insurance industry targets consumers, corporations, non-profit organizations and, in actuality, any entity that could be hurt financially by any type of risk, whether the risk is caused by natural events or human actions or behaviors.

The insurance industry offers its products and services to every person and every company in every industry subject to the risk appetite of each carrier. The insurance firm’s risk appetite is subject to a variety of attributes of the firm and the potential client, including the various exposures the potential client faces.

Exposures – of individual people, groups of people or companies – to a variety of risks (and in turn exposure to financial losses) where various insurance lines of business provide risk mitigation/management include:

- living too long

- dying too soon

- planning for college education of children

- retirement planning

- having a swimming pool in a homeowner’s property

- getting into an automobile accident

- manufacturing products

- managing a restaurant

- holding sporting events

- holding company picnics/outings

- using entertainment venues

- managing nursing/assisted living homes

- launching satellites.

In summary, insurance offers products and services to exposures of life, living, health, working, entertaining and conducting commerce (in any industry).

Skeleton Framework of the Insurance Industry

The insurance industry offers products (i.e., insurance policies) for the exposures articulated above and more within a specific industry structure: life and annuity (L&A), property and casualty (P&C), health (which I do not cover) and reinsurance (which I rarely if ever cover). [I realize this is a simplistic structure that omits other lines of insurance.]

I’ve included the visual below only to give a taste of the industry structure.

Value Proposition

The value proposition of the insurance industry, regardless of major line of business, is to mitigate or manage risks.

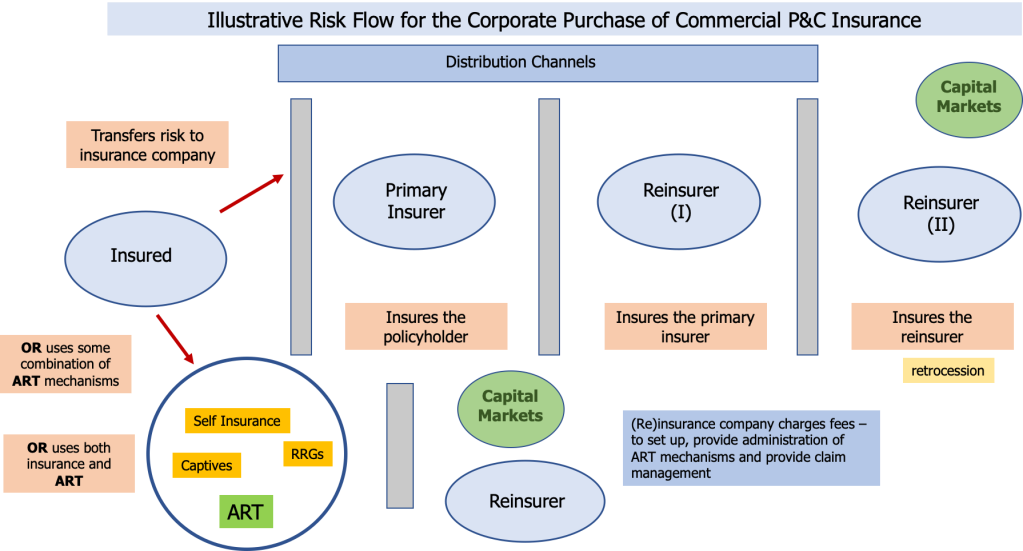

Let’s consider two value chains encompassing the flow of risk of the consumer purchase of insurance and of the corporate purchase of commercial P&C insurance.

My intention below is to show not just a flow of the acceptance of risk by some of the key participants in the insurance transaction but also to reinforce the complexity of the insurance transaction. I agree that consumers (i.e., individuals) don’t need to know the machinations behind their transactions but that ignorance doesn’t negate the complexities.

Illustrative Risk Flow for the Consumer Purchase of Insurance

Illustrative Risk Flow for the Corporate Purchase of Commercial P&C Insurance

See also: The Messaging Battle on COVID-19: Are Insurers Losing?

Profit Formula

Insurers generate their income from two main sources: premiums and investment income. To generate profitable premiums, insurers must strive for quality underwriting (i.e., to truly know the current and future exposures the prospective client faces through the intended length of the insurance policy).

To generate targeted investment income, insurers must strive for excellence in investing within the boundaries required by insurance regulators and must understand the current and future economy, political situation and insurance regulatory philosophies regarding all aspects of getting and keeping customers, whether retail or corporate.

Investment income

The acceptable investment areas are conservative in nature. For the U.S. life and accident and health insurance industry, for instance, the investment portfolio includes: bonds, preferred stock, common stock, mortgages, real estate, BA assets and cash. BA assets refers to the long-term invested assets as would be required to be reflected on Schedule BA of the NAIC Annual Statement Blank or the successor. For 2Q19, bonds represented 78% of the asset concentration.

Premiums

Premiums are the second major component of insurance company profitability. But insurers must strive for quality underwriting, and scale may not be an insurance company’s friend,.

Let’s discuss the concept of scale.

Scale

The mobile app that underwrites and binds an insurance policy within seconds (or nano-seconds) is the equivalent of a modern-day Frankenstein monster that runs amok through an insurance company’s financials, delivering rivers of blood red ink.

Why?

When a L&A or P&C insurance company underwrites and sells an insurance policy, it is simultaneously purchasing a future claim.

To ask two questions that every insurance (underwriting, actuarial, claims, marketing, sales and distribution) executive should consider with the sale of every insurance policy: What is the loss cost associated with the insured (i.e., policyholder), and when will that loss cost emerge for the insurer to adjudicate (and at what costs to adjudicate the claim, including any required investigations into possible fraud)?

The more insurers focus on scale, the more likely that they will incur underwriting losses.

L&A Insurers

The negative impact of scale is minimal for life insurance policies and annuities because L&A insurance companies have the Law of Large Numbers to use in addition to each L&A insurers’ own mortality and morbidity statistics and trends. L&A insurers, using these capabilities, can create models that have a high level of confidence predicting how many people (and more specifically their clients) will live during the year and also predict when death claims will occur. Still, L&A insurers need to to take care of the situations that are not candidates for simplified/accelerated underwriting (i.e., for those prospective insureds who don’t need a medical exam because of age, face amount of policy or other factors).

The negative impact of scale is more apparent for life insurers selling short-term disability (STD), long-term disability (LTD) and long-term care (LTC) insurance policies: These need to develop strong models to create predictions regarding occurrence – and cost – of claims. Mortality and morbidity statistics and trends obviously are in play in these markets. But so are a panoply of costs associated with delivering healthcare and physical rehabilitation. Scale is definitely not a desired attribute of STD, LTD or LTC sales.

P&C Insurers

The P&C market, whether personal or commercial, is where the Frankenstein monster of scale can truly run amok. I believe this holds true in the:

- personal lines P&C insurance market

- small commercial P&C insurance market

- mid-size commercial P&C insurance market of corporate clients that do not have risk managers or only have CFOs who are not experienced in purchasing commercial P&C insurance.

In these three markets, insurers must manage the attraction of scale by continually honing their risk appetites. This means that P&C insurers must focus their underwriting skills on prospective clients by creating policy conditions (encompassing terms, conditions and restrictions) that stipulate what exposures are covered (and not covered) and selling the policies at actuarially sound rates (that comply with insurance regulations, of course).

Technology Applications

The insurance industry is essentially an industry composed of a portfolio of processes to get and keep customers. There never was a time when the industry didn’t use technology applications to support each firm’s processes.

There are a myriad of ways to discuss the technology applications used by insurance firms. One path is to discuss the technology applications used to support not only the processes that insurance firms use to operate but also the technology applications that support the activities within each process. Another path encompasses selecting important business objectives of each insurance functional area/department and discussing the technology applications used to support those objectives.

I will use a systems perspective and discuss a few of the applications of technology in each of the systems:

- Systems of Record: The technology applications include those supporting the business objectives of quoting/rating, underwriting status/final decision, policy administration, billing and claims management.

- Systems of Customer Engagement: The technology applications include those supporting the business objectives of customer service, customer communication (using both analog and digital pathways), marketing campaigns, cross-sell/up-sell initiatives and customer satisfaction programs.

- Systems of Broker Management: The technology applications include those supporting broker calendaring/client appointments, broker training, broker pipeline management, broker/client communication, broker/insurer management (including campaign management), insurer downloading/certification requests, and broker productivity/profitability management.

- Systems of Decision-Making: The technology applications include those that support determining the effectiveness of marketing campaigns, measure agent/broker productivity or profitability, predict customer lifetime value, predict probable maximum loss (by customer, by market segment, by …) and model the potential premium flows from entering new markets or creating new products for existing markets.

Insurers should not use either Amazon’s or Netflix’s business model …

Finally, I can repeat my answer of "No, insurers should not use either Amazon’s or Netflix’s business model" and offer my reasoning. Without the discussion above, albeit a very lengthy discussion, I didn’t feel right about offering my reasoning to my response.

My reasoning is:

- Amazon’s and Netflix’s business models are built to quicken the sale of commodities.

- Insurance is not a commodity. This holds true for every line of insurance.

- Insurance, in several instances, is a legally required product (personal P&C insurance) or an expected product (commercial P&C insurance) or is just good sense to purchase (individual L&A; group life) to manage/mitigate the continually changing risk landscape to support people’s or companies' financial expectations or well-being.

- Amazon’s and Netflix’s business ,odels are built to enable and amplify scale.

- Scale is an enemy of insurance companies. In almost every insurable situation, insurers must apply stringent and high-quality underwriting skills to ensure profitable premium.

- While algorithms and models can be, and should be, used to assist insurance product development, sales, customer service, and claim adjudication processes, those algorithms and models must take into account that “one size does not fit all” and need to be tuned to meet the profit requirements of each insurer and to meet the changing regulatory requirements in each jurisdiction where the insurer and each of its distribution channels conduct insurance commerce.

- Amazon’s and Netflix’s business models are built to accommodate speed, particularly the speed of customers using mobile devices.

- Speed, like scale, can be an enemy of the insurance industry. Settling (either personal or commercial lines) P&C insurance claims quickly (within seconds or nano-seconds) can be a wonderful recipe for fraud.

- Speed of bringing new insurance customers onboard can also be a serious problem. Insurers must strive for quality underwriting (to generate profitable premium). Can that be done with algorithms? Yes. But the algorithm (besides needing to be approved by insurance regulators in every jurisdiction where the insurer wants to operate) should be personalized to each prospective customer and continually changed for new products, enhancements to existing products and for changing regulatory requirements.

- Amazon’s and Netflix’s business models' support of new products and services is hampered by funding needs. Netflix, specifically, is funding Netflix Originals with long-term debt.

- New insurance products and services have several hurdles to get to market, other than having the requisite funding, including at a minimum: ideation process involving participants from multiple departments, actuaries creating the actuarially sound rates (and reserves and surpluses), getting legal approval, training agents/brokers, training customer service representatives, creating claim adjudication practices, creating the requisite IT support, determining the amounts of ceded or assumed reinsurance if applicable and getting insurance regulatory approval.

- I am definitely not a financial analyst, but I’m not sure how well the philosophy of loading up on long-term debt to bring new products to market would appeal to insurance company executives.

- Moreover, there is the reality that insurance is not a book or a movie or a household appliance. It is a necessity (legally required in some instances) to mitigate or manage the risks to people’s lives, property, future financial requirements, actions and behaviors. (Put another way, no one is holding a gun to any person’s head and mandating that they use Amazon or Netflix.)

- Both Amazon’s and Netflix’s business models include recommendation engines enabled by machine learning.

- The insurance agent/broker serves as a “recommendation engine.” Slower than an algorithm obviously, but a repository (we hope) of the products and services that the various insurers s/he does business with that would be appropriate for the client. It would be helpful if insurers could create and provide machine-learning recommendation engines for their agents/brokers to use before or during an agent or broker’s sales meeting with prospective clients.

- One issue for insurers is to decide where to put the legally required skills and knowledge to conduct insurance commerce. Of course, insurers and the distribution channels know they have to have continual training and certification for each insurance line of business they want to sell in each jurisdiction. If the human is entirely replaced with an algorithm, that algorithm has to be continually retuned to meet insurance regulatory requirements.