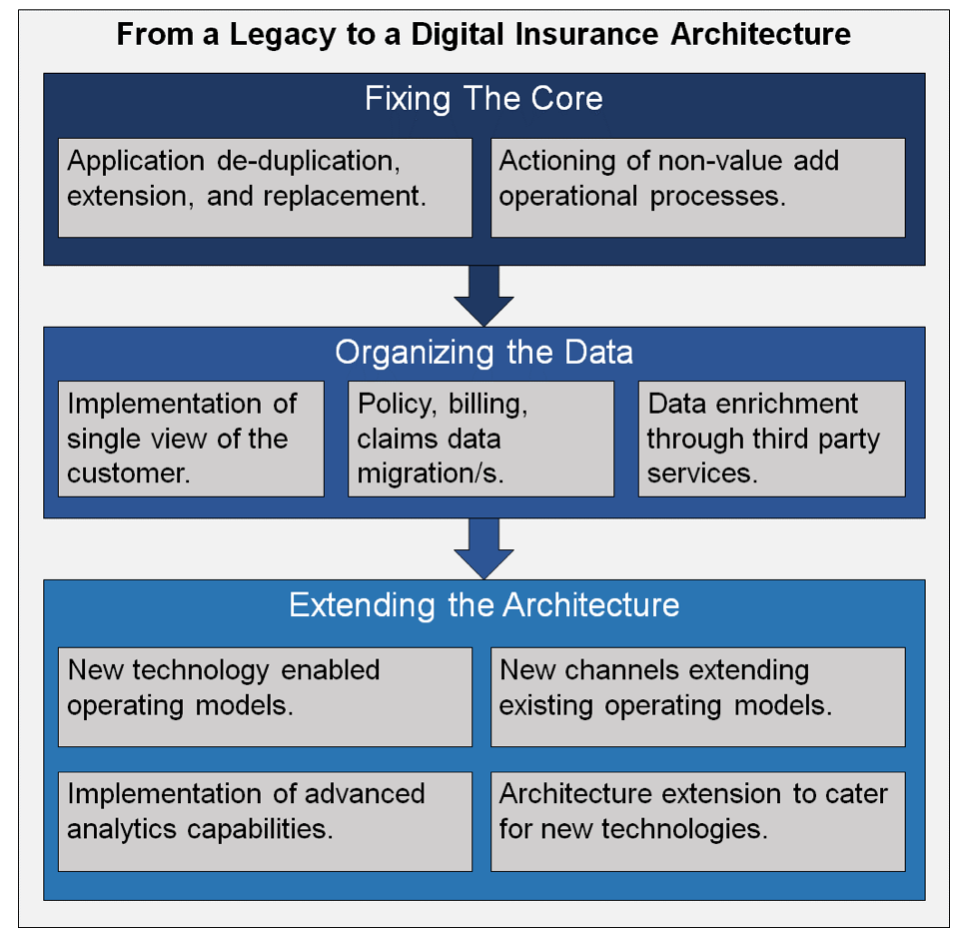

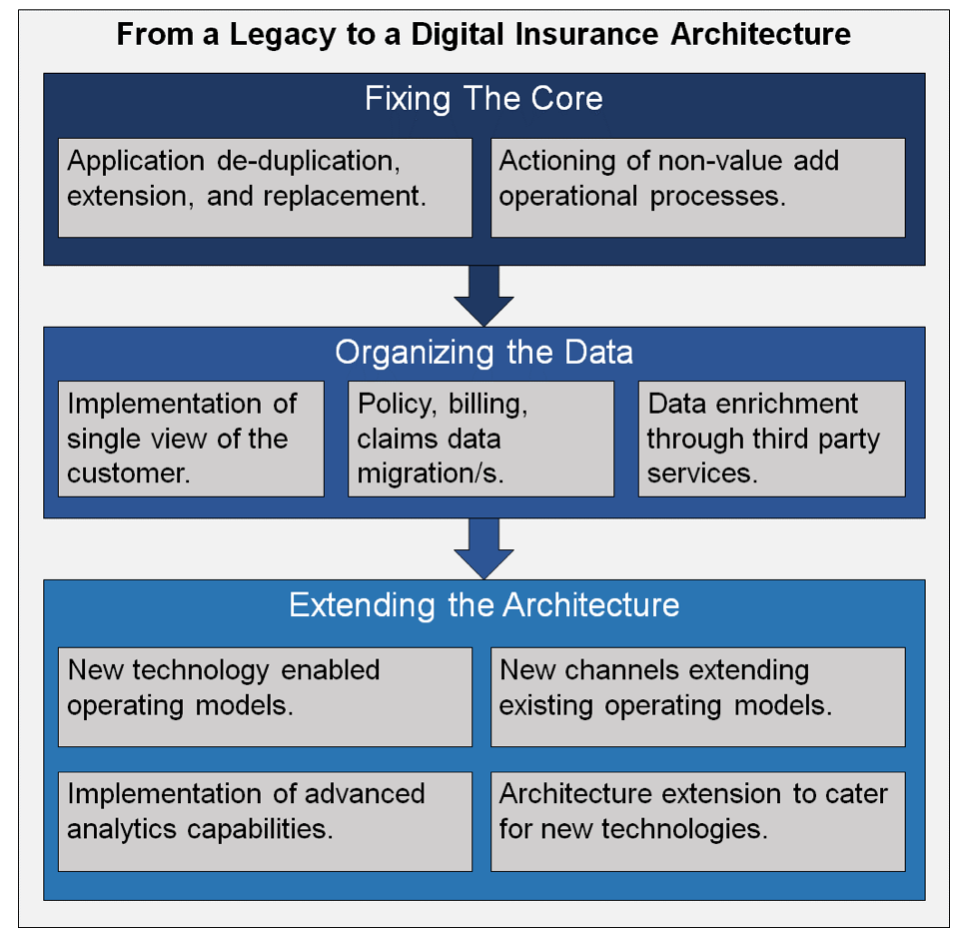

Progressing from a legacy application architecture constraining organizational strategy to a cutting-edge, digital-first application architecture driving organizational strategy is a goal for many insurers. To best achieve the transition, several steps are advisable. This article proposes a framework categorizing these steps into three distinct phases: fixing the core, organizing the data and extending the architecture.

Fixing the core

The first step requires addressing debt, both technical and operational, in an insurance application architecture, taking it to a baseline upon which the insurer can build. A number of elements should be considered.

First, each application in the as-is architecture should be assessed to identify candidate applications for de-duplication, extension and replacement.

De-duplication is justified where two or more applications perform overlapping functions. A common example is having claims applications that each cover a stage of the journey, even though each application could handle the entire claim. Another example is having multiple integration solutions, each covering a specific part of the architecture, such as policy, billing and claims.

Extension is advisable where there is benefit in maintaining a legacy application, but where significant improvements are required to specific elements. An example is a core policy-handling mainframe application carrying benefits with regard to cost and stability of operations, but imposing significant constraints on usability. The application could be extended by implementing a modern front end for users. A key point to consider is that extending legacy applications may introduce architectural complexity, increasing maintenance costs.

Where the underlying technology or functionality of a legacy application is significantly misaligned with the application strategy of the insurer, or where technical debt is so high that refactoring is no longer an option, then application replacement should be considered. Consult the insurer's application road map; If none are based on technologies akin to those of the application in question, then the application is likely not in line with the strategic direction. Technical debt, on the other hand, can be seen by analyzing the run cost of an application year on year; if the costs increase without a matching increase in supported functionality, then technical debt is accumulating.

See also: Digital Insurance, Anyone?

Second, operational processes should be analyzed to determine whether there are effort-heavy activities being performed as workarounds for technology limitations. An example is handlers manually keying claims data into a policy-handling application, then having to key the same data into a claims application because the integration between policy and claims does not work correctly. Another example is underwriters having to access multiple applications to find the data required to validate a policy renewal, because there is no single application where the data can be found. Where it becomes apparent that an operational process is merely acting as a band-aid for a technology limitation, then the relevant applications should be modified, extended or replaced.

Organizing the data

The second step is to organize the data held within the application architecture so that its value can be maximized:

- The insurer should analyze whether it has a single view of its customers across all applications, or whether records exist separately in multiple applications. If the latter, then the risk is that updates made in one application only may cause misalignments between party records. One option is to implement a Master Data Management (MDM) solution holding the golden record of the customer, then having all other applications refer to the golden record.

- The insurer should look at where its books of business are residing, and whether data migrations are required to move policies, claims, billing and other records from the source applications they reside on, to the insurer's strategic applications. If so, the insurer should determine the approach by which the data migrations will be performed, with the key options being automated Extract Transform Load (ETL) solutions, robotics applications and manual re-keying. If the source and target applications are multiple and varied, or if complex data transformations are required, then the migration process may require significant effort and planning.

- The insurer should consider how it can enrich its data through integration with third-party services, such as those providing credit score reports, or those providing specialized data such as real-time flood risk for specific postcodes. The insurer should keep in mind that every integration with a third-party application carries a financial, complexity and performance cost; the value of the data obtained should be greater than the cost of obtaining it.

Extending the architecture

Having built a solid platform, and having organized the data on it, the insurer can focus on extending the application architecture to achieve competitive differentiation. This can be done in innumerable ways; below are some ideas:

- The insurer could consider whether technology may support different operating models. For example, an insurer transacting through brokers alone may consider building a web front end allowing customers to perform quote and buy transactions. Similarly, an insurer lacking a customer-facing claims portal may consider building one.

- The insurer could consider whether its existing operating model could be extended through new channels. For example, a chatbot solution for claims First Notification of Loss (FNOL) could be built and integrated with a claims handling application. Similarly, an insurer could choose to integrate with a niche aggregator website to sell business that it previously only sold through brokers.

- The insurer could consider advanced analytics solutions. For example, the insurer may evaluate building an insights engine extracting data from key applications, normalizing and cleaning it to remove inconsistencies and duplication and presenting the data in management dashboards.

- The insurer could look at how to extend its application architecture to fit into its ambitions with regard to new technologies. For example, could anything be done to extend the architecture to accept data from IoT devices? Is artificial intelligence a real possibility on the current platform, or would structural changes be required? Robotics for operations is well established, but could robotics be applied to other use cases with the existing application landscape?

See also: Digital Insurance 2.0: Benefits

Analysis and Overview

Although the three proposed stages are an approximation, and the individual steps within them far from comprehensive, the hypothesis is that an order in which activities should be undertaken on the road to insurer application architecture digitization does exist. Supporting this hypothesis are the numerous cases in which insurers have embarked on large-scale digitization programs leveraging cutting-edge, architecture-extending, solutions, only to find years down the line that, because their cores had not been fixed and their data not correctly organized, their digitization efforts were hampered, if not blocked.

Key Points:

Key Points:

- The journey to insurer application architecture digitization is a multi-step process, and the steps can be categorized into three phases: fixing the core, organizing the data and extending the architecture.

- Fixing the core requires removing technical and operational debt associated with an insurance application architecture, taking the platform to a stable baseline.

- To organize the data, an insurer should evaluate whether it has a single view of its customers, whether data migrations are required and whether to integrate with data enrichment solutions.

- To extend its architecture, an insurer could consider enabling new operating models through technology adoption, implementing new technology-enabled channels, building advanced analytics capabilities and embedding into the architecture capabilities related to new technologies such as artificial intelligence and IoT.

- The hypothesis is that, although not rigid, an order of activities does exist, and insurers should consider fixing their cores and organizing their data before embarking on large-scale architecture extension.

Key Points:

Key Points: