The Future is Now

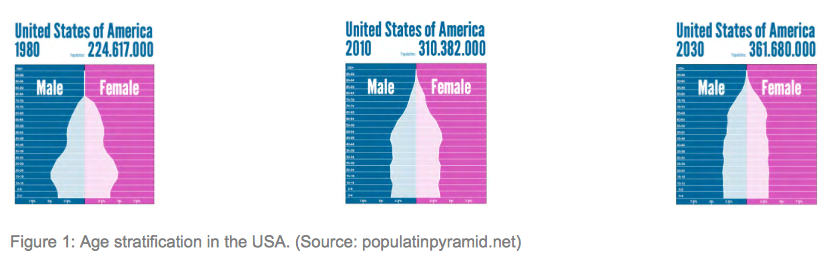

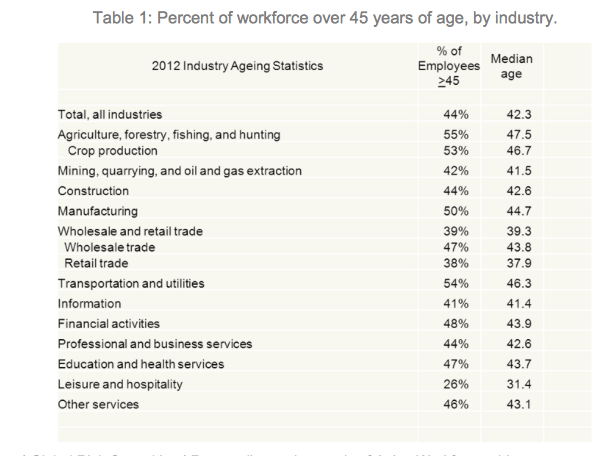

The time to discuss these trends as a “having potential impact in the future” has actually passed. We need to re-orient our thinking of the aging workforce as a new constant and as “today’s reality”. The medium age of some industries is as high as 55 (agriculture) indicating a need to act.

The Future is Now

The time to discuss these trends as a “having potential impact in the future” has actually passed. We need to re-orient our thinking of the aging workforce as a new constant and as “today’s reality”. The medium age of some industries is as high as 55 (agriculture) indicating a need to act.

Table 1: Percent of workforce over 45 years of age, by industry.

Table 1: Percent of workforce over 45 years of age, by industry.

The Birth of Ageonomics in Workers' Compensation

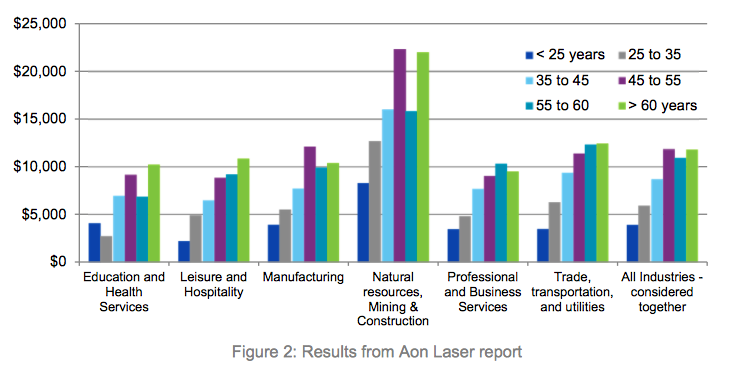

In 2011, we at Aon coined the term Ageonomics to address the phenomenon of the aging workforce and the strategies that can help address increased costs and worker safety. Vicki Missar, Aon board-certified ergonomist, defines Ageonomics as the scientific discipline concerned with the interaction among aging humans and other elements of the system within which they work.

Ultimately, Ageonomics is Aon’s professional service that applies theoretical principles to designing age-specific systems to optimize the wellbeing of the aging worker while improving overall system performance. Aon’s Ageonomics practice leverages the differentiated expertise of professionals spanning such disciplines as ergonomics, wellness, benefits and safety to deliver comprehensive and very powerful solutions to the aging workforce challenges most employers are facing.

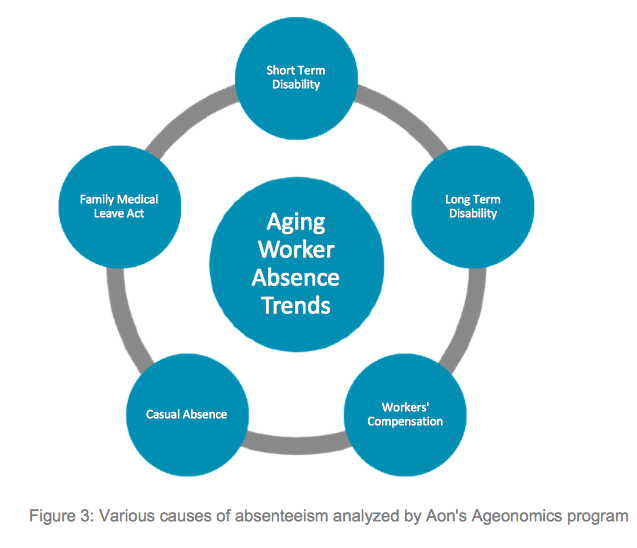

Ageonomics calibrates the absenteeism trends for the aging workforce, regardless of the bucket within which they fall. Aon analyzes the trends, from short-term disability (STD), long-term disability (LTD), workers' compensation (WC), casual absences (CA) and Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) absences to understand claim volume, average claim duration, average cost per lost day, average cost per claim, total costs and the ultimate cost projections. In addition to the financial output, Aon calibrates the leading absence causes by program type to understand what is driving the aging employee absenteeism. This insight provides clearer diagnosis on which programs are affecting the organization the greatest and which absenteeism causes are being reported with the most frequency. Aon also reviews the internal programs to understand how the framework is aligned with the organization’s aging worker initiatives. Organizations can then develop a targeted, age-specific strategy to help not only prevent or reduce the duration associated with the respective absences, but implement preemptive programs to help keep aging workers healthy and optimize their individual productivity.

The Birth of Ageonomics in Workers' Compensation

In 2011, we at Aon coined the term Ageonomics to address the phenomenon of the aging workforce and the strategies that can help address increased costs and worker safety. Vicki Missar, Aon board-certified ergonomist, defines Ageonomics as the scientific discipline concerned with the interaction among aging humans and other elements of the system within which they work.

Ultimately, Ageonomics is Aon’s professional service that applies theoretical principles to designing age-specific systems to optimize the wellbeing of the aging worker while improving overall system performance. Aon’s Ageonomics practice leverages the differentiated expertise of professionals spanning such disciplines as ergonomics, wellness, benefits and safety to deliver comprehensive and very powerful solutions to the aging workforce challenges most employers are facing.

Ageonomics calibrates the absenteeism trends for the aging workforce, regardless of the bucket within which they fall. Aon analyzes the trends, from short-term disability (STD), long-term disability (LTD), workers' compensation (WC), casual absences (CA) and Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) absences to understand claim volume, average claim duration, average cost per lost day, average cost per claim, total costs and the ultimate cost projections. In addition to the financial output, Aon calibrates the leading absence causes by program type to understand what is driving the aging employee absenteeism. This insight provides clearer diagnosis on which programs are affecting the organization the greatest and which absenteeism causes are being reported with the most frequency. Aon also reviews the internal programs to understand how the framework is aligned with the organization’s aging worker initiatives. Organizations can then develop a targeted, age-specific strategy to help not only prevent or reduce the duration associated with the respective absences, but implement preemptive programs to help keep aging workers healthy and optimize their individual productivity.

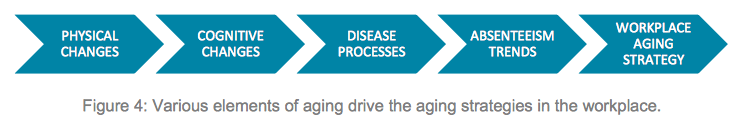

Changes Associated with Aging

The physiological changes associated with aging occur from the moment we are born. Fast forward to age 45 and older, and the body begins to change more significantly. Depending on primary factors such as health, fitness and genetics, all of us age differently. Researchers in Finland (Ilmarinen, et. al. 1997) found a decline in what they called "workability," with 51 years of age being the most critical point at which workability started to decrease. In addition, researchers noted that workability was shown to have a high predictive value for work disability (e.g. lower workability equals higher disability days). This means that we must now focus on the individual to understand age-related risk factors, modifiable and non-modifiable, to really address the challenges facing the aging workforce.

Physiological Changes That Can Affect Work Performance

With age comes decreased muscle strength, lower dexterity, reduced fitness level and aerobic capacity, poorer visual and auditory acuity and slower cognitive speed and function, to name a few. All of these changes can have a dramatic impact on the aging worker. For example, aging is related to the loss of muscle mass beginning at the age of 50 but becomes more dramatic at the age of 60 (Deschenes 2004). In addition to physical changes, older workers are at increased risk of disease and other ailments. These include the increased risk of obesity associated with aging, diabetes, heart disease, cancer and reduced fitness level, among others. Thus, prevention initiatives are needed to support the aging worker so that an effective, comprehensive strategy is developed. For example, if we know that muscle strength declines with age, organizations need to consider implementing safety, ergonomics and wellness programs to help build individual strength while working to reduce manual lifting, which could potentially result in injury or absence.

In the course of Aon’s Ageonomics diagnostic research, the two leading loss causes of injuries to knees and shoulders stem from strain/sprains and slip/trip/falls that can directly be attributed to reduced mobility and reduced strength, both of which can be related to an older physiology. By understanding the physical changes of an aging human and linking these changes to loss-producing trends in the data, we can develop a thoughtful strategy for increasing workability and reducing age-specific exposures in the workplace.

Changes Associated with Aging

The physiological changes associated with aging occur from the moment we are born. Fast forward to age 45 and older, and the body begins to change more significantly. Depending on primary factors such as health, fitness and genetics, all of us age differently. Researchers in Finland (Ilmarinen, et. al. 1997) found a decline in what they called "workability," with 51 years of age being the most critical point at which workability started to decrease. In addition, researchers noted that workability was shown to have a high predictive value for work disability (e.g. lower workability equals higher disability days). This means that we must now focus on the individual to understand age-related risk factors, modifiable and non-modifiable, to really address the challenges facing the aging workforce.

Physiological Changes That Can Affect Work Performance

With age comes decreased muscle strength, lower dexterity, reduced fitness level and aerobic capacity, poorer visual and auditory acuity and slower cognitive speed and function, to name a few. All of these changes can have a dramatic impact on the aging worker. For example, aging is related to the loss of muscle mass beginning at the age of 50 but becomes more dramatic at the age of 60 (Deschenes 2004). In addition to physical changes, older workers are at increased risk of disease and other ailments. These include the increased risk of obesity associated with aging, diabetes, heart disease, cancer and reduced fitness level, among others. Thus, prevention initiatives are needed to support the aging worker so that an effective, comprehensive strategy is developed. For example, if we know that muscle strength declines with age, organizations need to consider implementing safety, ergonomics and wellness programs to help build individual strength while working to reduce manual lifting, which could potentially result in injury or absence.

In the course of Aon’s Ageonomics diagnostic research, the two leading loss causes of injuries to knees and shoulders stem from strain/sprains and slip/trip/falls that can directly be attributed to reduced mobility and reduced strength, both of which can be related to an older physiology. By understanding the physical changes of an aging human and linking these changes to loss-producing trends in the data, we can develop a thoughtful strategy for increasing workability and reducing age-specific exposures in the workplace.

Rethinking the Work Environment

After some research and discussions with other benchmarking groups (NCCI and IBI), we can begin to make some educated assumptions surrounding drivers of these increased costs. What is of interest to Aon’s Ageonomics practice is how physical changes can influence solutions to reduce injury risk and prevent absenteeism. With onset of saropenia -- loss of muscle mass -- comes decreased strength. Many physically demanding jobs do not factor this into the equation when developing production standards or production demands for the workforce. By age-adjusting the demands by a specified factor, for example, we can not only reduce the risk of injury but improve the long-term workability and productivity of the workforce in general.

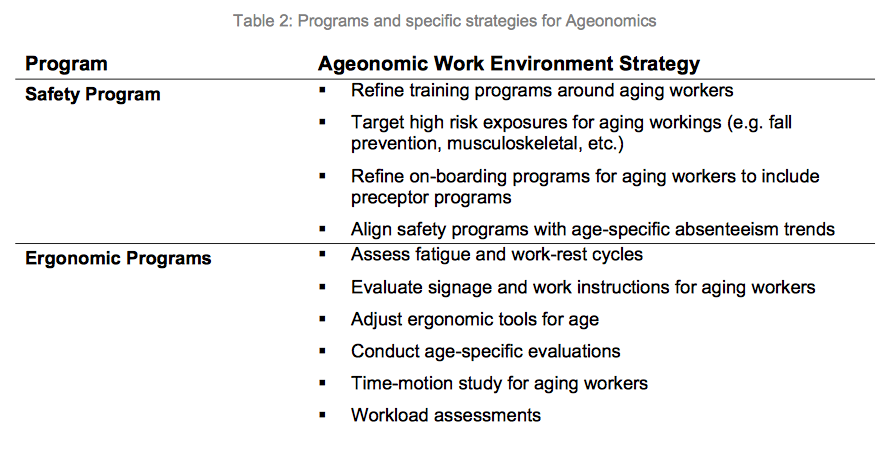

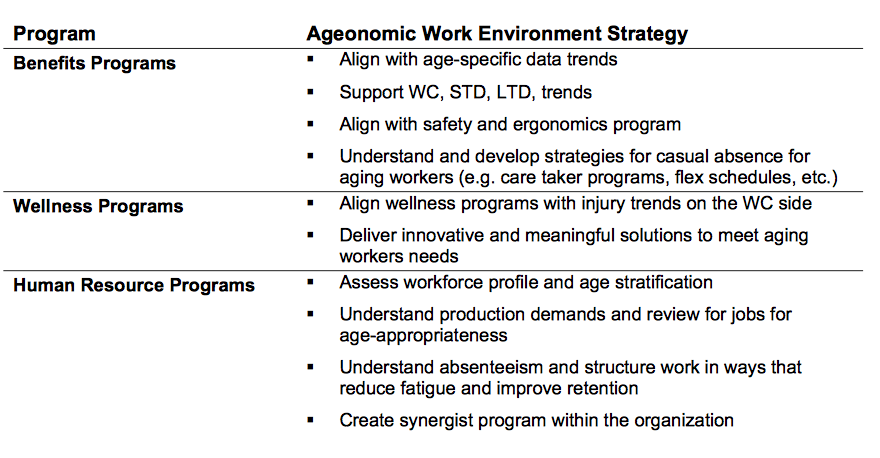

As part of Aon’s Ageonomics methodology, each safety, ergonomics, benefits, wellness, human-resource program aligns strategies and their resulting activities around the needs of the aging worker. The ultimate objective is to develop strategies geared toward optimizing the performance of the aging worker. This can only be done when each program is assessed and refined for the aging workforce (Table 2). For example, a recent study (Ruahala, et. al. 2007) found a linear trend between increasing workload and increasing sick time among nurses. First, we know that in health care and social assistance, musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) make up 42% of cases and have a rate of 55 cases per 10,000 full-time workers. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, this rate was 56% higher than the rate for all private industries and second only to the transportation and warehousing industry. Second, given that 55% of the USA nursing workforce is age 50 or older (NCSBN &The Forum of State Nursing Workforce), conducting an Ageonomics assessment may be an important part of a strategic program to reduce sick leave, workers' compensation injuries and overall absenteeism. Third, solutions cannot be one-dimensional, i.e., simply purchasing patient-handling equipment and hoping that will remedy the situation. Strategies must encompass the total health and wellbeing of the worker for optimal success, including a thorough review of the programs outlined in Table 2.

Rethinking the Work Environment

After some research and discussions with other benchmarking groups (NCCI and IBI), we can begin to make some educated assumptions surrounding drivers of these increased costs. What is of interest to Aon’s Ageonomics practice is how physical changes can influence solutions to reduce injury risk and prevent absenteeism. With onset of saropenia -- loss of muscle mass -- comes decreased strength. Many physically demanding jobs do not factor this into the equation when developing production standards or production demands for the workforce. By age-adjusting the demands by a specified factor, for example, we can not only reduce the risk of injury but improve the long-term workability and productivity of the workforce in general.

As part of Aon’s Ageonomics methodology, each safety, ergonomics, benefits, wellness, human-resource program aligns strategies and their resulting activities around the needs of the aging worker. The ultimate objective is to develop strategies geared toward optimizing the performance of the aging worker. This can only be done when each program is assessed and refined for the aging workforce (Table 2). For example, a recent study (Ruahala, et. al. 2007) found a linear trend between increasing workload and increasing sick time among nurses. First, we know that in health care and social assistance, musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) make up 42% of cases and have a rate of 55 cases per 10,000 full-time workers. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, this rate was 56% higher than the rate for all private industries and second only to the transportation and warehousing industry. Second, given that 55% of the USA nursing workforce is age 50 or older (NCSBN &The Forum of State Nursing Workforce), conducting an Ageonomics assessment may be an important part of a strategic program to reduce sick leave, workers' compensation injuries and overall absenteeism. Third, solutions cannot be one-dimensional, i.e., simply purchasing patient-handling equipment and hoping that will remedy the situation. Strategies must encompass the total health and wellbeing of the worker for optimal success, including a thorough review of the programs outlined in Table 2.

Rethinking Wellness As the U.S. workplace continues to age, it is critical to rethink wellness programs. Berry et. al. (2010)5 state in the Harvard Business Review:

Rethinking Wellness As the U.S. workplace continues to age, it is critical to rethink wellness programs. Berry et. al. (2010)5 state in the Harvard Business Review:

“Wellness programs have often been viewed as a nice extra, not a strategic imperative. Newer evidence tells a different story. With tax incentives and grants available under recent federal health care legislation, U.S. companies can use wellness programs to chip away at their enormous health care costs, which are only rising with an aging workforce.”

The article points out six pillars of an effective wellness program that can help significantly lower healthcare costs. As part of Aon’s Ageonomics practice, we analyze these pillars, including leadership, program quality, accessibility and communication of not only wellness but safety, ergonomics and other programs, to understand gaps for aging workers. By reviewing age-specific data and wellness program statistics, we can probe deeper and ultimately develop strategies to better align these programs for the aging worker. Researchers at Harvard found that participants in wellness programs are absent less often and perform better at work than their nonparticipant counterparts. Thus, structuring a wellness program around aging workers can become a way for organizations to not only retain aging workers but ensure their workability does not decline to levels that result in disabilities and workers' compensation claims. Conclusions As with any workplace program, measuring success includes not only healthcare costs, but workers' compensation costs, safety program incident rates, absenteeism and turnover rates, among other indicators. It becomes essential to align traditional silo programs and produce a synergistic, thoughtful approach to optimize any program touching an aging worker. For a copy of the full Aon white paper on which this article is based, click here.