The claims operation poses a vital opportunity for insurance organizations to drive efficiency, cost savings and customer satisfaction. A modern claims platform—native to the Internet—is key. However, many insurance organizations still use outdated systems that are sluggish, lack contemporary claims-handling capabilities and cannot easily adapt to the industry’s evolving business needs.

In this article, we’ll discuss: the drivers that are leading more organizations to modernize; key criteria for a modern platform; strategies for successful implementation; key considerations for configuration; and the importance of user training. Finally, we’ll review the benefits that organizations can achieve by leveraging modern infrastructure.

Drivers to Modernize

An organization’s claims strategy is the cornerstone to its competitive advantage. The claims process represents a major touch point with customers, and the quality of the service provided during these transactions has the potential to make or break long-term customer relationships. An investment in modernizing claims will go a long way toward not only improving customer service but also boosting the bottom line.

Claims currently cost the property and casualty industry $40 billion just to administer, and it’s a process that would significantly benefit from an investment in IT infrastructure improvements. A typical claims department has more work and increasingly more data to manage. The sheer volume of transactions and a lack of automation tools have prevented staff from being able to focus on key tasks that would truly improve costs and outcomes. In addition, these departments are hampered by traditional bottlenecks in efficiency, including manual, paper-based operations and disjointed workflow.

Many organizations still have legacy system, which are slow and frequently crash. Maintaining these outdated platforms is not only expensive—consuming as much as 80% of IT budgets—but they also force organizations to resort to labor-intensive workarounds to process claims and to get the data they need. These systems are resistant to change and integration with other solutions.

Outdated systems also make the analysis of claims data cumbersome. Organizations spend significant time and IT resources to develop data queries, but oftentimes the resulting reports don’t contain the information required, so organizations have to start over. A modern platform leverages sophisticated data mining tools, so organizations don’t miss vital opportunities to reduce costs and improve their operations.

Within insurance, organizations must continually respond to new regulatory requirements as well as launch products and service capabilities. Organizations must be able to implement changes on the fly, preferably at the direction of business users rather than at the mercy of busy IT staff. This type of flexibility empowers organizations to continually rethink and reengineer workflow to meet compliance and business needs.

Many organizations dissatisfied with legacy systems rushed out to obtain browser-based applications, not realizing that first-generation solutions grew out of their legacy counterparts. Many first-generation systems still possessed an ineffectual design and faced significant performance issues.

Today’s next-generation, browser-based solutions are truly modern and native to the Internet, offering more flexibility and capability.

Building a Strategic Plan

With continual expansion and increased transactions, more organizations are outgrowing their current IT infrastructure. As a result, many are beginning to outline a plan to modernize. Such plans must project claims management needs, along with strategic business objectives, so organizations can support not only near-term goals but also a long-term vision. These plans must consider the selection and implementation of new systems, as well as configuration, integration and optimization of new and existing systems to optimize the overall enterprise.

Criteria for a Modern Platform

A modern platform must support an organization’s ability to grow and expand, and accommodate changing system and business needs over a period of five to 10 years. In addition, a modern platform must meet two critical requirements—in-depth claims-handling and extreme flexibility—both of which can help organizations align the system to their evolving claims and business strategy. From an architectural standpoint, a modern platform must scale well, handling both a large volume of transactions and a large number of users.

Modern platforms are capable of tightly integrating data, systems and people to facilitate streamlined workflow and enhanced decision-making. The platform must offer a wide range of integration options, including pre-built connectors, batch processing, Web services and other custom interfaces. Integration is essential to connect claims with other internal and external systems and stakeholders. Modern solutions have a track record of innovation, continually investing in new features, tools and capabilities.

Newer solutions also incorporate business intelligence (BI) and data mining tools. BI has the power to revolutionize the way organizations analyze data and predict trends. These tools deliver the information needed to improve results and minimize risk. They often use data cubes to pre-aggregate information and generate reports at amazingly fast speeds and with dynamic viewing capabilities, helping organizations make critical business decisions.

Strategies for Implementation Success

Implementing a new system can be expensive, resource-intensive and disruptive to day-to-day operations. Not surprisingly, many projects fail—while others fall behind schedule, go over budget or don’t provide the anticipated benefits.

An experienced solutions provider will outline an in-depth implementation plan and walk organizations through the process to avoid common missteps. Many vendors use an agile implementation process, which is iterative and incremental, thereby enabling the vendor to expedite the delivery of requirements, incorporate client-requested changes and reduce the risk of project delays or going over budget.

A typical implementation can take six to 18 months, depending on the scope of the project, the lines of business affected and the number of systems being replaced. Many organizations have chosen to utilize a phased implementation approach, so they can deploy the solution sooner—perhaps with one or two lines of business. This allows them to reap an immediate return, while also gaining hands-on experience with the system to better configure it for the next phase of implementation.

Key Considerations for Configuration

Time and consideration should be given to configure a new system to meet unique claims workflow and process needs. An organization must consider what screens are important, as well as whether it may need to collect unique information through customized screens and data fields. Business rules should be set up to manage and automate workflow, as well as to trigger alerts for events that require supervisory review. In addition, reports should be configured, so, once the system goes live, they’ll be ready and automatically delivered to the relevant stakeholders.

Establishing user rights and restrictions also helps facilitate quality control in the claims process. Management may want to restrict user rights and access within the system, according to the type of user. For example, management could assign full, partial or read-only access. One organization granted nurse case managers access to only the case management portion of claim files. Another restricted inexperienced adjusters from setting high reserves or significantly increasing reserves. Instead, such actions required a supervisor’s review and approval.

A Commitment to Training

Another key factor for success is extensive and thorough system training for users. Organizations should consider scheduling training two months before the go-live date to begin to familiarize users with the look and feel of the system, and a second training immediately before “go live” to ensure users are comfortable with the claims workflow within the new system environment.

Certainly, technology cannot replace the intuition, analysis or personal service that claims professionals provide. Claims staff should understand how the technology will help them to better apply their expertise. For example, by automating administrative functions, they can focus on knowledge-based and service-oriented tasks.

Business users who will be responsible for updating the system to accommodate new requirements must be trained on a continuing basis. These users will define system changes—whether it’s for a new report, workflow or supervisor alert—so they must understand the system logic. Organizations must commit to keeping these users up to date, especially as new versions and tools become available.

Key Benefits and Cost Savings

As more organizations modernize, they’re beginning to realize the extensive business benefits that can be achieved, including the following:

- Reduce claims costs. Modernization enables an organization to better manage claims costs and outcomes. Organizations will have the reporting tools they need to identify high-cost areas and take advantage of opportunities for savings.

- Leverage data. With dashboards, business intelligence tools and reporting platforms, modern systems help facilitate both a big-picture and granular view of claims. With this understanding, organizations can make business decisions that improve the bottom line.

- Introduce products. When organizations introduce insurance policy products, they must configure operations to handle incoming claims. A modern system can help make updates to the claims side quickly and easily.

- Enhance customer service. A modern platform helps organizations facilitate the delivery of timely, responsive and personalized service.

- Improve operational efficiency. Organizations have increased the efficiency and productivity of claim departments, particularly with the use of business rules for task automation and document management for paperless claims processing. With these improvements, organizations have seen a significant return on investment.

- Leverage IT benefits. Because of the superior design of modern systems, IT departments benefit from the ease of maintenance, security and upgrades. Staff member are freed to spend more time on projects such as process enhancements.

- Ease the burden of compliance. Continuing to comply with new and emerging regulations can be an administrative and financial burden. Compliance is complex, but modern systems automate, streamline and facilitate the compliance process.

Keeping Pace for the Future

Insurance leaders are striving to continually improve their claims operation. Today, leveraging modern technology is a primary means to that end. The IT strategies discussed in this article are making it easier to administer and automate complex claims transactions, which involve multiple parties, multiple systems and various regulatory concerns.

As adopters have found, the more complex and cumbersome the claims transaction, the greater the opportunity for modern systems to improve efficiency, savings and service. Modern platforms also incorporate data mining and reporting to enable organizations to obtain insights to further drive performance.

In the end, there is no blanket solution, but, above all else, organizations need infrastructure capable of accommodating the ever-changing insurance market.

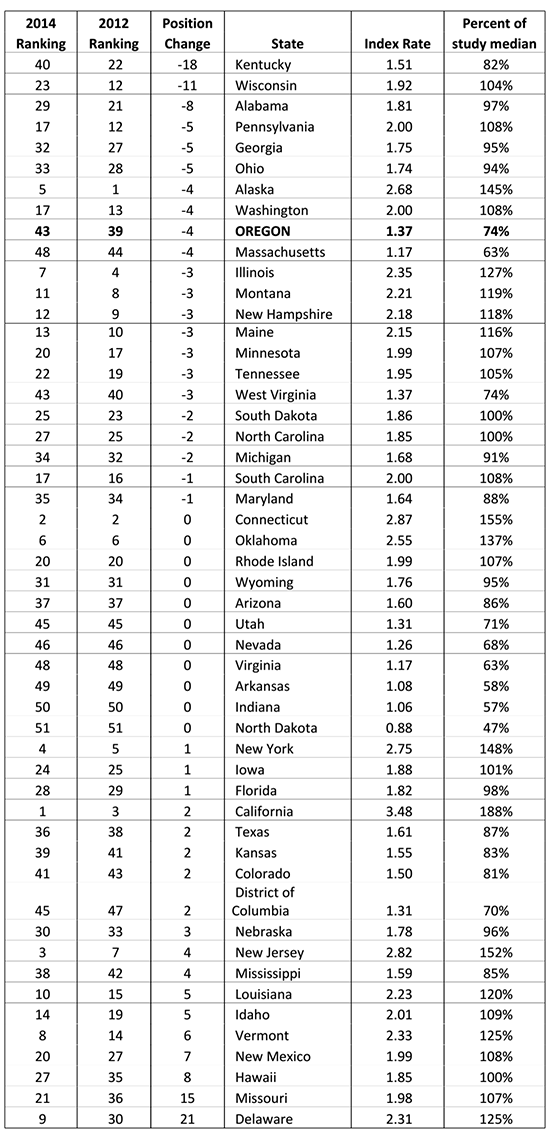

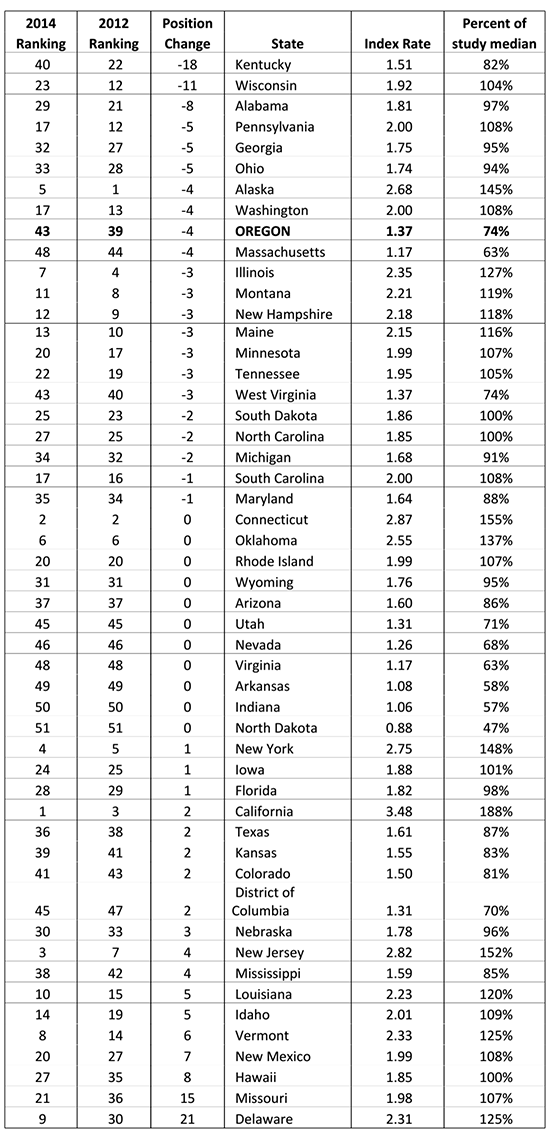

We can see that there were major drops in premium rank for both Kentucky and Wisconsin. Kentucky moved from 22nd-highest in the nation to 40th, improving by 18 positions. Wisconsin moved down 11 spots, from 12th-highest to 23rd. While Wisconsin did enact some changes in 2012, neither state is considered to have been a major reform state over the last few years.

For a couple of those states undergoing dramatic reforms, Oklahoma and Tennessee, it is too early to tell the effect, as they are just implementing changes this year. Others, however, including California and Kansas, saw premium costs as a comparative rise despite reforms intended to do otherwise. Illinois, another reform state, did see some positive movement, but it is probably not statistically significant given the weight of the costs and issues in that state.

I would postulate based on this report that people in New Mexico, Hawaii, Missouri and Delaware may be thinking of what changes should be in order, because they had dramatic negative movement on the scale this year. Even if past reforms overall are not creating significant improvement in these numbers, I am pretty sure they will be a better predictor of what states may be facing reform in the future.

Oregon has conducted these studies in even-numbered years since 1986, when Oregon’s rates were among the highest in the nation. The department reports the results to the Oregon legislature as a performance measure. Oregon’s relatively low rate today reflects the state’s workers’ compensation system reforms and its improvements in workplace safety and health.

Here are some key links for the study/workers’ compensation costs:

• To read a summary of the study, go here.

• Prior years’ summaries and full reports with details of study methods can be found here.

• Information on workers’ compensation costs in Oregon, including a map with these state rate rankings, is here.

We can see that there were major drops in premium rank for both Kentucky and Wisconsin. Kentucky moved from 22nd-highest in the nation to 40th, improving by 18 positions. Wisconsin moved down 11 spots, from 12th-highest to 23rd. While Wisconsin did enact some changes in 2012, neither state is considered to have been a major reform state over the last few years.

For a couple of those states undergoing dramatic reforms, Oklahoma and Tennessee, it is too early to tell the effect, as they are just implementing changes this year. Others, however, including California and Kansas, saw premium costs as a comparative rise despite reforms intended to do otherwise. Illinois, another reform state, did see some positive movement, but it is probably not statistically significant given the weight of the costs and issues in that state.

I would postulate based on this report that people in New Mexico, Hawaii, Missouri and Delaware may be thinking of what changes should be in order, because they had dramatic negative movement on the scale this year. Even if past reforms overall are not creating significant improvement in these numbers, I am pretty sure they will be a better predictor of what states may be facing reform in the future.

Oregon has conducted these studies in even-numbered years since 1986, when Oregon’s rates were among the highest in the nation. The department reports the results to the Oregon legislature as a performance measure. Oregon’s relatively low rate today reflects the state’s workers’ compensation system reforms and its improvements in workplace safety and health.

Here are some key links for the study/workers’ compensation costs:

• To read a summary of the study, go here.

• Prior years’ summaries and full reports with details of study methods can be found here.

• Information on workers’ compensation costs in Oregon, including a map with these state rate rankings, is here.

We can see that there were major drops in premium rank for both Kentucky and Wisconsin. Kentucky moved from 22nd-highest in the nation to 40th, improving by 18 positions. Wisconsin moved down 11 spots, from 12th-highest to 23rd. While Wisconsin did enact some changes in 2012, neither state is considered to have been a major reform state over the last few years.

For a couple of those states undergoing dramatic reforms, Oklahoma and Tennessee, it is too early to tell the effect, as they are just implementing changes this year. Others, however, including California and Kansas, saw premium costs as a comparative rise despite reforms intended to do otherwise. Illinois, another reform state, did see some positive movement, but it is probably not statistically significant given the weight of the costs and issues in that state.

I would postulate based on this report that people in New Mexico, Hawaii, Missouri and Delaware may be thinking of what changes should be in order, because they had dramatic negative movement on the scale this year. Even if past reforms overall are not creating significant improvement in these numbers, I am pretty sure they will be a better predictor of what states may be facing reform in the future.

Oregon has conducted these studies in even-numbered years since 1986, when Oregon’s rates were among the highest in the nation. The department reports the results to the Oregon legislature as a performance measure. Oregon’s relatively low rate today reflects the state’s workers’ compensation system reforms and its improvements in workplace safety and health.

Here are some key links for the study/workers’ compensation costs:

• To read a summary of the study, go here.

• Prior years’ summaries and full reports with details of study methods can be found here.

• Information on workers’ compensation costs in Oregon, including a map with these state rate rankings, is here.

We can see that there were major drops in premium rank for both Kentucky and Wisconsin. Kentucky moved from 22nd-highest in the nation to 40th, improving by 18 positions. Wisconsin moved down 11 spots, from 12th-highest to 23rd. While Wisconsin did enact some changes in 2012, neither state is considered to have been a major reform state over the last few years.

For a couple of those states undergoing dramatic reforms, Oklahoma and Tennessee, it is too early to tell the effect, as they are just implementing changes this year. Others, however, including California and Kansas, saw premium costs as a comparative rise despite reforms intended to do otherwise. Illinois, another reform state, did see some positive movement, but it is probably not statistically significant given the weight of the costs and issues in that state.

I would postulate based on this report that people in New Mexico, Hawaii, Missouri and Delaware may be thinking of what changes should be in order, because they had dramatic negative movement on the scale this year. Even if past reforms overall are not creating significant improvement in these numbers, I am pretty sure they will be a better predictor of what states may be facing reform in the future.

Oregon has conducted these studies in even-numbered years since 1986, when Oregon’s rates were among the highest in the nation. The department reports the results to the Oregon legislature as a performance measure. Oregon’s relatively low rate today reflects the state’s workers’ compensation system reforms and its improvements in workplace safety and health.

Here are some key links for the study/workers’ compensation costs:

• To read a summary of the study, go here.

• Prior years’ summaries and full reports with details of study methods can be found here.

• Information on workers’ compensation costs in Oregon, including a map with these state rate rankings, is here.