With the official start of the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season just one month away, there has likely never been a more important one for the insurance industry. This is not just because most of the early-season guidance points to an above-average hurricane season, which could increase the chances of hurricane landfall along the U.S. coastline; but, because of COVID-19, if a hurricane makes landfall it comes with increasing pressures for the people affected and the stress on the insurance industry. With insurers already strained due to COVID-19, additional losses from a named storm could disrupt the industry.

By their very nature, hurricanes force people to gather close together in shelters and travel away from their places of residency during evacuations. This goes directly against what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend for countering a Covid-19 outbreak. Think about when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005: Around 20,000 people took refuge in the Superdome. One building with 20,000 people can’t happen in the current environment. Additionally, we have all read that the elderly population is more susceptible to COVID-19 and that the CDC guidelines should be strictly followed for this demographic, but the elderly are even more at risk during a hurricane because COVID-19 complicates evacuation procedures that are already difficult for them.

COVID-19 is already placing unprecedented strain on disaster management, health and other systems; a hurricane will exacerbate that strain. With outbreaks across the entire nation, an area hit by a hurricane is less likely to get aid from other states or regions. Will power crews travel hundreds of miles to help restore power? The lack of quick response can further create problems with mold growth if the power is not restored fast enough. After a storm, sometimes as many as 10,000 volunteers come from all over to help with the recovery, but it might be hard finding volunteers amid the pandemic. How about claims adjusters and another insurance personal that need to inspect property damage? How about contractors getting into an area to put tarps on roofs and prevent further damage? The list is almost endless of how uncertainty increases.

This is why all eyes will be on any little disturbance that develops anywhere in the Atlantic Ocean this season.

Atlantic Hurricane Forecasts Are a Dime a Dozen

Do you know there are at least 26 different entities that forecast various aspects of the Atlantic hurricane season? You can track the majority of the early season predictions here: http://seasonalhurricanepredictions.org.

In meteorology forecasting class, one of the lessons that is taught is that the consensus forecast is a hard forecast to beat. Although early April hurricane season forecasts for activity have the least amount of overall reliability, when you get a great number of forecasts that agree that the overall activity will be above normal it should get the attention of the insurance industry.

See also: The Best Tools for Disaster Preparation

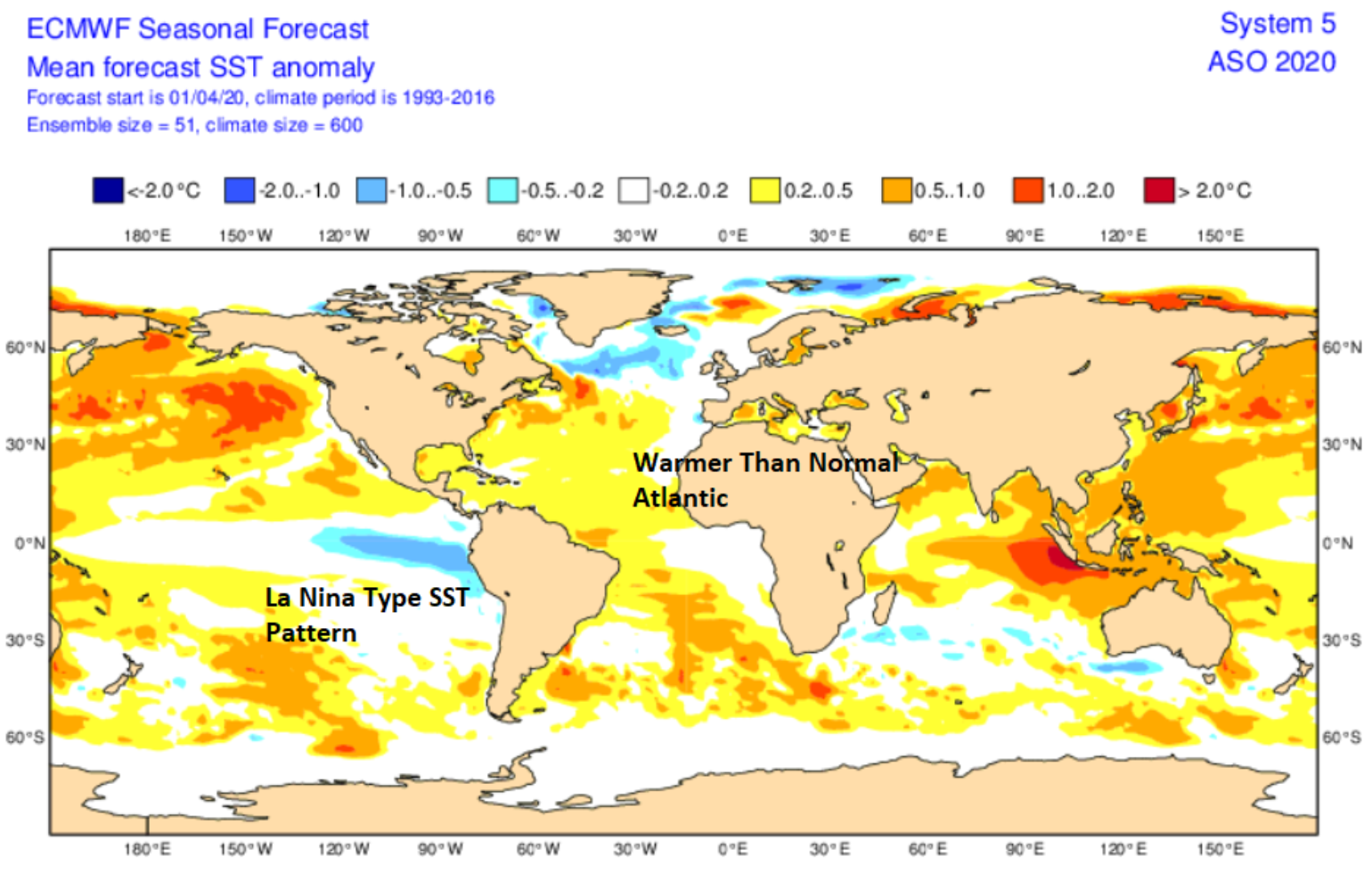

All the forecasts speculate on the same general climate factors that are leading indicators to an active hurricane season. One is the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Currently, the majority of the global ENSO forecast models call for ENSO-neutral conditions during the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season for August-October. When ENSO is warmer than normal, it is called El Niño, and it typically reduces Atlantic hurricane activity via increased upper-level westerly winds in the Caribbean extending into the tropical Atlantic that shear apart storms as they are trying to form. This is not forecast to occur this year. There is some indication that late in the summer months a La Niña might develop, which would bring even less wind shear to the Caribbean and might lead to above normal activity. From 1995-2019, the non-El Niño seasonal mean Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index across the Atlantic Basin is 160 (104 is the 1981-2010 average), with those non-El Niño years having an average of 16 named storms, eight hurricanes and four major hurricanes across the basin. So this is a good place to start if one wants to make the argument for more favorable activity across the Atlantic basin.

The other major climate forcer leading to an above-normal forecast is the Atlantic Sea Surface Temperature (SST), which is unusually warm at this time. This early-season warmth in the Main Development Region (MDR) has a strong relationship to an active hurricane season as a catalyst to tropical waves that move off Africa.

Historically, warmer than normal sea surface temperatures in the eastern Atlantic correlate with more active Atlantic #hurricane season. Currently, most of the eastern Atlantic is warmer than normal, except for north of 45°N. pic.twitter.com/SAkM5DX7VS

— Philip Klotzbach (@philklotzbach) May 4, 2020

While these warm SSTs could change before the summer, the fact that the air temperatures over the area will only get warmer will likely limit any cooling of the current SST. Together with the increased probability of La Niña, the Atlantic SST signals elevated chances of a busy Atlantic hurricane season.

If you haven’t noticed, there has been plenty of severe weather in the Southeast U.S. over the last month or so. Part of the blame of these severe weather outbreaks can also be put on the warmer than normal SST in the Gulf of Mexico feeding moisture into the Southeast as mid-latitude low-pressure systems pull moisture up from the Gulf of Mexico, where water temperatures are one to three degrees above normal. There is no relationship between April Gulf SST and annual hurricane activity, mainly because Gulf of Mexico conditions can change quickly over a given season with weather pattern shifts. However, if such anomalies persist into July, the temperature could be deeply unsettling.

A wildcard to the season could be how much dry air rolls off the coast of Africa with tropical waves. There have been seasons where all the major climate forcers looked to align, but named storms need the precise set of ingredients to come together to make for a super active year, and dry air can be a wildcard; too much dry air aloft can inhibit named storm development.

Landfall Analogs

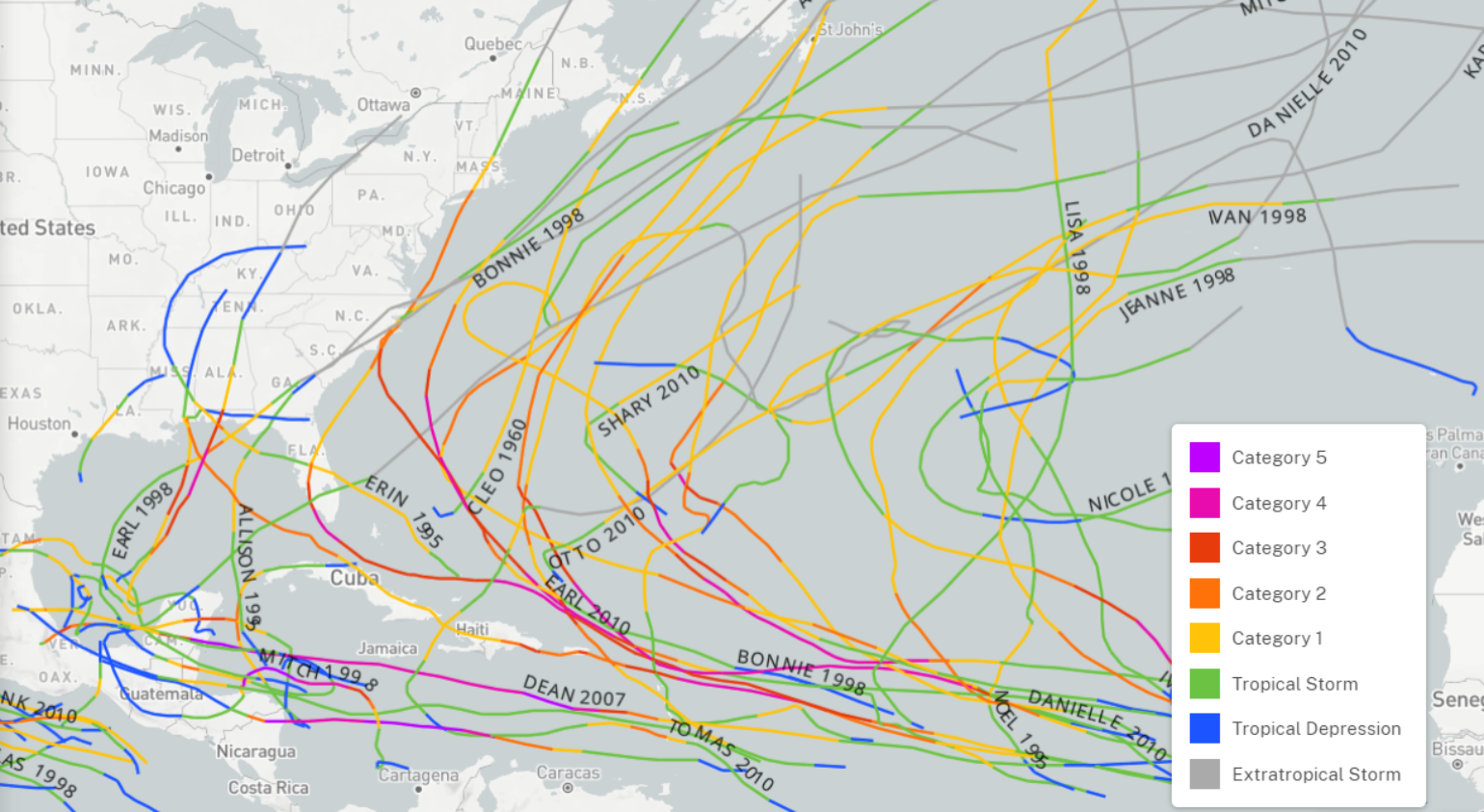

Many of the seasonal hurricane forecasts shy away from the most important factor for the insurance industry, which is overall landfall activity. After all, the Atlantic basin can be very active, but if no hurricanes make landfall the impact on the insurance industry is irrelevant. By looking at current oceanic and atmospheric conditions that are similar to conditions now and that might be expected during the peak of the hurricane season, analog years can provide useful clues as to what type of landfall activity might occur for the 2020 Atlantic Hurricane season. The years that seem to be most common are 1960, 1995, 1998, 2007, 2010 and 2013.

The analog years suggest a clustering of a pattern that would point to named storm activity along the central Gulf Coast and the Outer Banks. There is also a cluster of activity north of Puerto Rico and in the western Caribbean. In general, the analogs point to years with named storm landfall activity, so landfalling named storms should be expected from Texas to Maine, with the most focus on the regions mentioned above.

See also: Flood Insurance: Are the Storm Clouds Lifting?

Early Season Activity

By now, the insurance industry understands that often tropical named storm activity comes in waves, which is largely a result of the passage of the Madden–Julian Oscillation (MJO) or large scale Convectively Coupled Kelvin Wave (CCKW). As we approach the start of the Atlantic hurricane season, the insurance industry can start to get a sense of when the Atlantic basin might experience some activity. The latest forecast guidance suggests that the first such wave of activity might occur around May 11, with another coming shortly after the start of the Atlantic Hurricane season. Given that the last five hurricane seasons have produced at least one named storm before June 1, it wouldn't surprise me if this year tried to follow suit given the warm SST in the Gulf of Mexico. Often, early season development occurs with storm activity off the Carolina coastline. These types of early systems tend to meander or make landfall along the North Carolina to northeast Florida coastline. But another area ripe for early season activity this year could be in the Gulf of Mexico.

Summary

The season looks to be active with a higher probability of named storm landfalls along the Gulf Coast or Outer Banks, NC, raising many questions about the possible effects on the insurance industry.

As the BMS Property Practice pointed out, if there is a heightened risk along the U.S. coastline would the authorities even allow non-permanent residents into the area to reach a second home if their primary residence is out of state?

Who is going to take steps to limit damage? How will storm response hamper recovery efforts in terms of volunteers or field adjusters? If hotels are not operating, where do people go, where do adjusters stay?

Maybe this is the year that insurtech solutions help the insurance industry respond to a natural disaster in new ways. No matter how you look at it, we are entering uncharted territory this hurricane season.